List of atheist authors

This is a list of atheist authors. Mentioned in this list are people whose atheism is relevant to their notable activities or public life, and who have publicly identified themselves as atheists.

Authors

A–B

- Jason Aaron (born 1973): American comics writer, known for his work on The Other Side, Scalped, Ghost Rider, Wolverine and PunisherMAX.[1]

- Forrest J Ackerman (1916–2008): American writer, historian, editor, collector of science fiction books and movie memorabilia and a science fiction fan. He was, for over seven decades, one of science fiction's staunchest spokesmen and promoters.[2]

- Douglas Adams (1952–2001): British radio and television writer and novelist, author of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.[3] 9

- Dushyant (born 1977): Indian poet, lyricist, author

- Javed Akhtar (born 1945): Indian poet, lyricist and scriptwriter.[4]

- Adalet Ağaoğlu (1929–2020): Turkish author and activist.[5]

- Tariq Ali (born 1943): British-Pakistani historian, novelist, filmmaker, political campaigner and commentator.[6]

- Jorge Amado (1912–2001): Brazilian author.[7]

- Eric Ambler, OBE (1909–1998): English writer of spy novels who introduced a new realism to the genre.[8]

- Kingsley Amis (1922–1995): English novelist, poet, critic and teacher, most famous for his novels Lucky Jim and the Booker Prize-winning The Old Devils.[9]

- Seth Andrews (born 1968): American author and host of The Thinking Atheist radio podcast.[10] He is the author of two books, Deconverted (2012)[10] and Sacred Cows (2015).[11]

- Philip Appleman (1926–2020): poet, novelist and professor emeritus of English literature.[12]

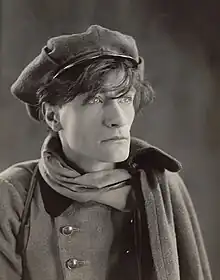

- Antonin Artaud (1896–1948): French playwright, poet, actor and theatre director. Known for The Theatre and its Double.[13]

- Isaac Asimov (1920–1992): Russian-born American author of science fiction and popular science books.[14]

- Diana Athill (1917–2019): British literary editor, novelist and memoirist who worked with some of the writers of the 20th century.[15]

- James Baldwin (1924–1987): American novelist, essayist, playwright, poet, and social critic.[16]

- J. G. Ballard (1930–2009): English novelist, short story writer, and prominent member of the New Wave movement in science fiction. His best-known books are Crash and the semi-autobiographical Empire of the Sun.[17]

- Iain Banks (1954–2013): Scottish author, writing mainstream fiction as Iain Banks and science fiction as Iain M. Banks.[18] Known especially for a collection of ten science-fiction novels and anthologies called The Culture series.

- Henri Barbusse (1873–1934): French novelist, journalist and communist politician.[19]

- Julian Barnes (born 1946): English writer. Barnes won the Man Booker Prize for his book The Sense of an Ending (2011).[20]

- Dave Barry (born 1954): American author and columnist, who wrote a nationally syndicated humor column for the Miami Herald from 1983 to 2005. Barry is the son of a Presbyterian minister, and decided "early on" that he was an atheist.[21]

- Simone de Beauvoir (1908–1986): French feminist writer and existentialist philosopher, who was the author of She Came to Stay and The Mandarins.[22]

- Gregory Benford (born 1941): American science fiction author and astrophysicist.[23]

- Toni Bentley: Author of The Surrender[24] and Sisters of Salome.[25]

- Pierre Berton, CC, O.Ont (1920–2004): Noted Canadian author of non-fiction, especially Canadiana and Canadian history, and was a well-known television personality and journalist.[26]

- Annie Besant (1847–1933): British author, orator, and activist who, about her conversion to atheism, She wrote, "The path from Christianity to Atheism is a long one, and its first steps are very rough and very painful."[27]

- Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (1840–1922): English poet, writer and diplomat.[28]

- William Boyd, CBE (born 1952): Scottish novelist and screenwriter.[29]

- Charles Bradlaugh (1833–1891): British author, orator, and politician who "abandoned Christianity for atheism" to "become the most powerful British propagandist for atheism."[30]

- Lily Braun (1865–1916): German feminist writer.[31]

- Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956): German poet, playwright, theatre director, and Marxist.[32]

- Howard Brenton (born 1942): English playwright, who gained notoriety for his 1980 play The Romans in Britain.[33]

- André Breton (1896–1966): French writer, poet, artist, and surrealist theorist, best known as the main founder of surrealism.[34][35][36][37]

- Brigid Brophy, Lady Levey (1929–1995): English novelist, essayist, critic, biographer, and dramatist.[38]

- Alan Brownjohn (born 1931): English poet and novelist.[39]

- Charles Bukowski (1920–1994): American author.[40]

- John Burroughs (1837–1921): American naturalist and essayist important in the evolution of the U.S. conservation movement.[41]

- Lawrence Bush (born 1951): Author of several books of Jewish fiction and non-fiction, including Waiting for God: The Spiritual Explorations of a Reluctant Atheist.[42]

- Mary Butts (1890–1937): English modernist writer.[43]

C–D

- João Cabral de Melo Neto, (1920–1999): Brazilian poet[44]

- Henry Cadbury (1883–1974): a biblical scholar and Quaker who contributed to the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible.[45]

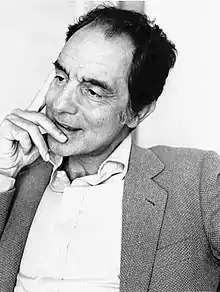

- Italo Calvino (1923–1985): Italian journalist and writer of short stories and novels. His best known works include the Our Ancestors trilogy (1952–1959), the Cosmicomics collection of short stories (1965), and the novels Invisible Cities (1972) and If on a winter's night a traveler (1979).[46]

- John W. Campbell (1910–1971): American science fiction writer and editor.[47]

- Albert Camus (1913–1960): French philosopher and novelist who has been considered a luminary of existentialism. He won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1957.[48][49]

- Giosuè Carducci (1835–1907): Italian poet and teacher. In 1906, he became the first Italian to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.[50]

- Angela Carter (1940–1992): English novelist and journalist, known for her feminist, magical realism and science fiction works.[51]

- Anton Chekhov (1860–1904): Russian physician, dramatist, and author who is considered to be among the greatest writers of short stories in history.[52][53][54][55]

- Staceyann Chin, performance artist and poet, who early in her life decided to always tell the truth, and blurted out the essentials of her life story to a housemate, including the declaration: "I'm not a Christian anymore, I don't believe in God."[56]

- Greta Christina (born 1961): American blogger, speaker, and author.[57][58]

- Sir Arthur C. Clarke (1917–2008): British scientist and science-fiction author.[59]

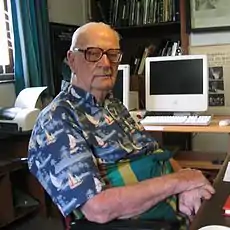

- Edward Clodd (1840–1930): English banker, writer and anthropologist, an early populariser of evolution, keen folklorist and chairman of the Rationalist Press Association.[60]

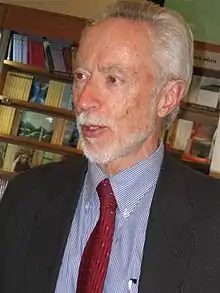

- J. M. Coetzee (born 1940): South African novelist, essayist, linguist, translator, and recipient of the 2003 Nobel Prize in Literature; now an Australian citizen.[61]

- Claud Cockburn (1904–1981): Radical British writer and journalist, controversial for his communist sympathies.[62]

- G. D. H. Cole (1889–1959): English political theorist, economist, writer and historian.[63]

- Ivy Compton-Burnett DBE (1884–1969): English novelist.[64]

- Cyril Connolly (1903–1974): English intellectual, literary critic and writer.[65]

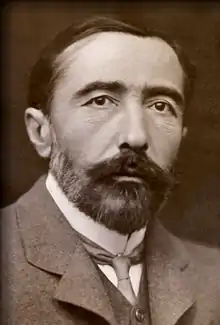

- Joseph Conrad (1857–1924): Polish novelist who wrote in English.[66]

- Edmund Cooper (1926–1982): English poet and prolific writer of speculative fiction and other genres, published under his own name and several pen names.[67]

- William Cooper (1910–2002): English novelist.[68]

- Paul-Louis Couchoud (1879–1959), French philosopher and psychiatrist, a proponent of the Christ myth thesis, author of The Creation of Christ (1937/1939).

- Jim Crace (born 1946): English writer, winner of numerous awards.[69]

- Theodore Dalrymple (born 1949): pen name of British writer and retired physician Anthony Daniels.[70]

- Akshay Kumar Datta (1820–1886): Bengali writer.[71]

- Rhys Davies (1901–1978): Welsh novelist and short story writer.[72]

- Frank Dalby Davison (1893–1970): Australian novelist and short story writer, best known for his animal stories and sensitive interpretations of Australian bush life.[73]

- Richard Dawkins (born 1941): British ethologist, evolutionary biologist and popular science author. He was formerly Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford and a fellow of New College, Oxford. Author of books such as The Selfish Gene (1976), The Blind Watchmaker (1986) and The God Delusion (2006).

- Alain de Botton (born 1969), author of Religion for Atheists: A Non-Believer's Guide to the Uses of Religion, 2012.[74]

- Daniel Dennett (born 1942): American author and philosopher.[75]

- Marquis de Sade (1740–1814): French aristocrat, revolutionary and writer of philosophy-laden and often violent pornography.[76]

- Isaac Deutscher (1907–1967): British journalist, historian and biographer.[77]

- Thomas M. Disch (1940–2008): American science fiction author and poet, winner of several awards.[78]

- Carlo Dossi (1849–1910): Italian writer and diplomat.[79]

- Roddy Doyle (born 1958): Irish novelist, dramatist and screenwriter, winner of the Booker Prize in 1993.[80]

- Theodore Dreiser (1871–1945): American writer and journalist of the naturalist school.[81]

- Carol Ann Duffy (born 1955): Award-winning British poet, playwright and freelance writer.[82]

- Friedrich Dürrenmatt (1921–1990): Swiss writer and dramatist.

- Turan Dursun (1934–1990): Islamic scholar, imam and mufti, and latterly, an outspoken atheist.[83]

E–G

- Terry Eagleton (born 1943): British literary critic, currently Professor of English Literature at the University of Manchester.[84]

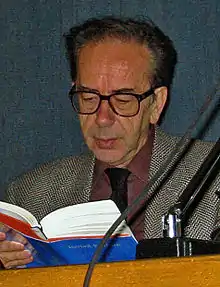

- Umberto Eco (1932–2016): Italian semiotician, essayist, philosopher, literary critic, and novelist.[85]

- Ruth Dudley Edwards (born 1944): Irish historian, crime novelist, journalist and broadcaster.[86]

- Greg Egan (born 1961): Australian computer programmer and science fiction author.[87][88]

- Dave Eggers (born 1970): American writer, editor, and publisher.[89]

- Barbara Ehrenreich (born 1941): American feminist, socialist and political activist. She is a widely read columnist and essayist, and the author of nearly 20 books.[90][91]

- Bart D. Ehrman (born 1955): renowned biblical scholar at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who became an atheist after struggling with the philosophical problems of evil and suffering.[92]

- George Eliot (1819–1890): Mary Ann Evans, the famous novelist, was also a humanist and propounded her views on theism in an essay, "Evangelical Teaching".[93]

- Harlan Ellison (1934–2018): American science fiction author and screenwriter.[94]

- F. M. Esfandiary/FM-2030 (1930–2000): Transhumanist writer and author of books such as Identity Card, The Beggar, UpWingers, and Are You a Transhuman. In several of his books, he encouraged readers to "outgrow" religion, and that "God was a crude concept-vengeful wrathful destructive."[95]

- Dylan Evans (born 1966): British academic and author who has written books on emotion and the placebo effect as well as the theories of Jacques Lacan.[96]

- Gavin Ewart (1916–1995): British poet.[97]

- Michel Faber (born 1960): Dutch author who writes in English, wrote the Victorian-set postmodernist novel The Crimson Petal and the White.[98]

- Oriana Fallaci (1929–2006): Italian journalist, author, and political interviewer.[99]

- Vardis Fisher (1895–1968): American writer and scholar, author of atheistic Testament of Man series.[100]

- Tom Flynn (1955–2021): American author and Senior Editor of Free Inquiry magazine.[101]

- Ken Follett (born 1949): British author of thrillers and historical novels.[102]

- John Fowles (1926–2005): English novelist and essayist, noted especially for The French Lieutenant's Woman and The Magus.[103]

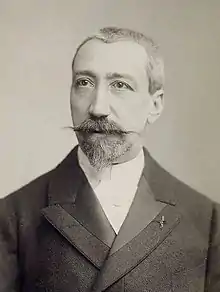

- Anatole France (1844–1924): French novelist and journalist, Nobel Prize in Literature (1921).[104]

- Maureen Freely (born 1952): American journalist, novelist, translator and teacher.[105]

- James Frey (born 1969): American author, screenwriter and director.[106]

- Stephen Fry (born 1957): British author, actor and television personality

- Frederick James Furnivall (1825–1910): English philologist, one of the co-creators of the Oxford English Dictionary.[107]

- Alex Garland (born 1970): British novelist and screenwriter, author of The Beach and the screenplays for 28 Days Later, Sunshine, Ex Machina, among others.[108]

- Constance Garnett (1861–1946): English translator, whose translations of nineteenth-century Russian classics first introduced them widely to the English and American public.[109]

- Nicci Gerrard (born 1958): British author and journalist, who with her husband Sean French writes psychological thrillers under the pen name of Nicci French.[110]

- Rebecca Goldstein (born 1950): American novelist and professor of philosophy.[111]

- Nadine Gordimer (1923–2014): South African writer and political activist. Her writing has long dealt with moral and racial issues, particularly apartheid in South Africa. She won the Nobel Prize in literature in 1991.[112][113]

- Maxim Gorky (1868–1936): Russian and Soviet author who founded Socialist Realism and political activist.[114]

- Antonio Gramsci (1891–1937): Italian writer, politician, political philosopher, and linguist.[115]

- Robert Graves (1895–1985): English poet, scholar, translator and novelist, producing more than 140 works including his famous annotations of Greek myths and I, Claudius.[116]

- Graham Greene OM, CH (1904–1991): English novelist, short story writer, playwright, screenwriter, travel writer and critic.[117][118]

- Germaine Greer (born 1939): Australian feminist writer. Greer describes herself as a "Catholic atheist".[119]

- David Grossman (born 1954): Israeli author of fiction, nonfiction, and youth and children's literature.[120]

- Jan Guillou (born 1944): Swedish author and journalist.[121]

H–K

- Mark Haddon (born 1962): British author of fiction, notably the book The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time (2003).[122][123]

- Daniel Handler (born 1970): American author better known under the pen name of Lemony Snicket. Declared himself to be 'pretty much an atheist'[124] and a secular humanist.[125] Handler has hinted that the Baudelaires in his children's book series A Series of Unfortunate Events might be atheists.[126]

- Lorraine Hansberry (1930–1965): African–American playwright and author of political speeches, letters, and essays. Best known for her work, A Raisin in the Sun.[127]

- Yip Harburg (1896–1981): American popular song lyricist who worked with many well-known composers. He wrote the lyrics to the standards "Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?", "April in Paris", and "It's Only a Paper Moon", as well as all of the songs in The Wizard of Oz, including "Over the Rainbow." He also wrote a book of poetry, criticizing religion, "Rhymes for the Irreverent" [128]

- Sam Harris (born 1967): American author, researcher in neuroscience, author of The End of Faith and Letter to a Christian Nation.[129]

- Harry Harrison (1925–2012): American science fiction author, anthologist and artist whose short story The Streets of Ashkelon took as its hero an atheist who tries to prevent a Christian missionary from indoctrinating a tribe of irreligious but ingenuous alien beings.[130]

- Tony Harrison (born 1937): English poet, winner of a number of literary prizes.[131]

- Zoë Heller (born 1965): British journalist and novelist.[132]

- Theodor Herzl (1860–1904): Austro-Hungarian journalist and writer who founded modern political Zionism.[133]

- Pierre-Jules Hetzel (1814–1886): French editor and publisher. He is best known for his extraordinarily lavishly illustrated editions of Jules Verne's novels highly prized by collectors today.[134]

- Dorothy Hewett (1923–2002): Australian feminist poet, novelist, librettist, and playwright.[135]

- Archie Hind (1928–2008): Scottish writer, author of The Dear Green Place, regarded as one of the greatest Scottish novels of all time.[136]

- Christopher Hitchens (1949–2011): Author of God Is Not Great, journalist and essayist.[137]

- R. J. Hollingdale (1930–2001): English biographer and translator of German philosophy and literature, President of The Friedrich Nietzsche Society, and responsible for rehabilitating Nietzsche's reputation in the English-speaking world.[138]

- Michel Houellebecq (born 1958): French novelist.

- A. E. Housman (1859–1936): English poet and classical scholar, best known for his cycle of poems A Shropshire Lad.[139]

- Keri Hulme (1947–2021): New Zealand writer, known for her only novel The Bone People.[140]

- Stanley Edgar Hyman (1919–1970): American literary critic who wrote primarily about critical methods.[141]

- Henrik Ibsen (1828–1906): Norwegian playwright, theatre director, and poet. He is often referred to as "the father of prose drama" and is one of the founders of Modernism in the theatre.[142]

- Howard Jacobson (born 1942): British author, best known for comic novels but also a non-fiction writer and journalist. Prefers not to be called an atheist.[143][144]

- Susan Jacoby (born 1945): American author, whose works include the New York Times best seller The Age of American Unreason, about anti-intellectualism.[145]

- Clive James (1939–2019): Australian author, television presenter and cultural commentator.[146][147]

- Robin Jenkins (1912–2005): Scottish writer of about 30 novels, though mainly known for The Cone Gatherers.[148]

- Diana Wynne Jones (1934–2011): British writer. Best known for novels such as Howl's Moving Castle and Dark Lord of Derkholm.[149]

- Neil Jordan (born 1950): Irish novelist and filmmaker.[150]

- S. T. Joshi (born 1958): American editor and literary critic.[151]

- Ismail Kadare (born 1936): Albanian novelist and poet, winner of the Prix mondial Cino Del Duca, the Jerusalem Prize, and the inaugural Man Booker International Prize.[152][153]

- Franz Kafka (1883–1924), Jewish Czech-born writer. Best known for his short stories such as The Metamorphosis and novels such as The Castle and The Trial.[154][155][156][157][158][159][160]

- K. Shivaram Karanth (1902–1997): Kannada writer, social activist, environmentalist, Yakshagana artist, film maker and thinker.[161]

- James Kelman (born 1946): Scottish author, influential and Booker Prize-winning writer of novels, short stories, plays and political essays.[162]

- Douglas Kennedy (born 1955): American-born novelist, playwright and nonfiction writer.[163]

- Ludovic Kennedy (1919–2009): British journalist, author, and campaigner against capital punishment and for voluntary euthanasia.[164]

- Marian Keyes (born 1963): Irish writer, considered to be one of the original progenitors of "chick lit", selling 22 million copies of her books in 30 languages.[165]

- Danilo Kiš (1935–1989): Serbian and Yugoslavian novelist, short story writer and poet who wrote in Serbo-Croatian. His most famous works include A Tomb for Boris Davidovich and The Encyclopedia of the Dead.

- Paul Krassner (1932–2019): American founder and editor of the freethought magazine The Realist, and a key figure in the 1960s counterculture.[166]

L–M

- Pär Lagerkvist (1891–1974): Swedish author who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1951. He used religious motifs and figures from the Christian tradition without following the doctrines of the church.[167]

- Philip Larkin CH, CBE, FRSL (1922–1985): English poet, novelist and jazz critic.[168][169]

- Stieg Larsson (1954–2004): Swedish journalist, author of the Millennium Trilogy and the founder of the anti-racist magazine Expo.[170]

- Marghanita Laski (1915–1988): English journalist and novelist, also writing literary biography, plays and short stories.[171]

- Rutka Laskier (1929–1943): Polish Jew who was killed at Auschwitz concentration camp at the age of 14. Because of her diary, on display at Israel's Holocaust museum, she has been dubbed the "Polish Anne Frank."[172]

- Anton Szandor LaVey (1930–1997): founder of LaVeyan Satanism and Church of Satan.[173]

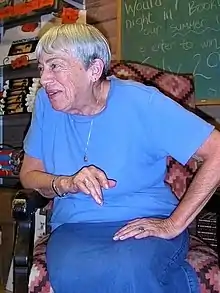

- Ursula K. Le Guin (1929–2018): American author. She has written novels, children's books, and short stories, mainly in the genres of fantasy and science fiction.[174][175]

- Stanisław Lem (1921–2006): Polish science fiction novelist and essayist.[176]

- Giacomo Leopardi (1798–1837): Italian poet, linguist, essayist and philosopher. Leopardi is legendary as an out-and-out nihilist.[177]

- Primo Levi (1919–1987): Italian novelist and chemist, survivor of Auschwitz concentration camp. Levi is quoted as saying "There is Auschwitz, and so there cannot be God."[178]

- Michael Lewis (born 1960): American financial journalist and non-fiction author of Liar's Poker, Moneyball, The Blind Side: Evolution of a Game and The Big Short[179][180]

- Sinclair Lewis (1885–1951): American novelist, short-story writer, and playwright. In 1930, he became the first writer from the United States to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was awarded "for his vigorous and graphic art of description and his ability to create, with wit and humor, new types of characters."[181]

- Georg Christoph Lichtenberg (1742–1799): German scientist, satirist, philosopher and anglophile. Known as one of Europe's best authors of aphorisms. Satirized religion using aphorisms like "I thank the Lord a thousand times for having made me become an atheist."[182]

- Eliza Lynn Linton (1822–1898): Victorian novelist, essayist, and journalist.[183]

- John W. Loftus (born 1954): Former Evangelical minister. Author of Why I Became an Atheist, The Christian Delusion, The End of Christianity, and The Outsider Test for Faith. Host of the website, Debunking Christianity.

- Jack London (1876–1916): American author, journalist, and social activist.[184][185]

- Pierre Loti (1850–1923): French novelist and travel writer.[186]

- H. P. Lovecraft (1890–1937): American horror writer.[187]

- Franco Lucentini (1920–2002): Italian writer, journalist, translator and editor of anthologies.[188]

- Lucian (125–180): Roman Syrian rhetorician and satirist who wrote in Greek; a religious skeptic and debunker[189] often regarded as an atheist in the modern sense,[190] whose position in the Roman Imperial administration makes it unlikely he professed atheism[191]

- Norman MacCaig (1910–1996): Scottish poet, whose work is known for its humour, simplicity of language and great popularity.[192]

- Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) "was [...] a connoisseur of depravity; an atheist who passionately hated the clergy, who thought the institution of the Catholic Church should be dismantled [...]"[193]

- Colin Mackay (1951–2003): British poet and novelist.[194]

- David Marcus (1924–2009): Irish Jewish editor and writer, a lifelong advocate and editor of Irish fiction.[195]

- Roger Martin du Gard (1881–1958): French author, winner of the 1937 Nobel Prize for Literature.[196]

- Stephen Massicotte (born 1969): Canadian playwright, screenwriter and actor.[197]

- Aroj Ali Matubbar (1900–1985): Bengali writer.

- W. Somerset Maugham CH (1874–1965): English playwright, novelist, and short story writer, one of the most popular authors of his era.[198][199]

- Joseph McCabe (1867–1955): English writer, anti-religion campaigner.[200]

- Mary McCarthy (1912–1989): American writer and critic.[201]

- James McDonald (born 1953): British writer, whose books include Beyond Belief, 2000 Years Of Bad Faith In The Christian Church[202]

- Ian McEwan, CBE (born 1948): British author and winner of the Man Booker Prize.[203]

- Barry McGowan (born 1961): American non-fiction author.[204]

- China Miéville (born 1972): British science fiction and fantasy author.[205]

- Arthur Miller (1915–2005): American playwright and essayist, a prominent figure in American literature and cinema for over 61 years, writing a wide variety of plays, including celebrated plays such as The Crucible, A View from the Bridge, All My Sons, and Death of a Salesman, which are widely studied.[206]

- Christopher Robin Milne (1920–1996): Son of author A. A. Milne who, as a young child, was the basis of the character Christopher Robin in his father's Winnie-the-Pooh stories and in two books of poems.[207]

- David Mills (born 1959): Author who argues in his book Atheist Universe that science and religion cannot be successfully reconciled.[208]

- Octave Mirbeau (1846–1917): French novelist, playwright, art critic and journalist.[209]

- Terenci Moix (1942–2003): Spanish writer who wrote in both Spanish and in Catalan.[210]

- Brian Moore (1921–1999): Irish novelist and screenwriter, awarded the James Tait Black Memorial Prize in 1975 and the inaugural Sunday Express Book of the Year award in 1987, was shortlisted for the Booker Prize three times.[211]

- Alberto Moravia (1907–1990): Italian novelist, essayist and journalist.[212]

- Sir John Mortimer, CBE QC (1923–2009): English barrister, dramatist and author, famous as the creator of Rumpole of the Bailey.[213]

- Andrew Motion FRSL (born 1952): English poet, novelist and biographer, and Poet Laureate 1999–2009.[214]

- Clare Mulley (born 1969): Author of The Woman Who Saved the Children (2009), The Spy Who Loved, and The Women Who Flew for Hitler.[215]

- Dame Iris Murdoch (1919–1999): Dublin-born writer and philosopher, best known for her novels, which combine rich characterization and compelling plotlines, usually involving ethical or sexual themes.[216]

- Douglas Murray (born 1971): British neoconservative writer and commentator.[217]

N–R

- Pablo Neruda (1904–1973): Chilean poet and diplomat. In 1971, he won the Nobel Prize for Literature.[218]

- Aziz Nesin (1915–1995): Turkish humorist and author of more than 100 books.[219]

- Larry Niven (born 1938): American science fiction author. His best-known work is Ringworld (1970).[220]

- Michael Nugent (born 1961): Irish writer and activist, chairperson of Atheist Ireland.[221]

- Joyce Carol Oates (born 1938): American author and Professor of Creative Writing at Princeton University.[222]

- Redmond O'Hanlon (born 1947): British author, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.[223]

- John Oswald (activist) (c.1760–1793): Scottish journalist, poet, social critic and revolutionary.[224]

- Arnulf Øverland (1889–1968): Norwegian author who in 1933 was tried for blasphemy after giving a speech named "Kristendommen – den tiende landeplage" (Christianity – the tenth plague), but was acquitted.[225]

- Camille Paglia (born 1947): American post-feminist literary and cultural critic.[226][227]

- Robert L. Park (1931–2020): scientist, University of Maryland professor of physics, and author of Voodoo Science and Superstition.[228]

- Frances Partridge (1900–2004): English member of the Bloomsbury Group and a writer, probably best known for the publication of her diaries.[229]

- Pier Paolo Pasolini (1922–1975): Italian poet, intellectual, film director, and writer.[230]

- Raj Patel: (born 1972, London) is a British-born American academic, journalist, activist and writer, known for his 2008 book, Stuffed and Starved: The Hidden Battle for the World Food System. His most recent book is The Value of Nothing, which was on The New York Times best-seller list during February 2010.[231]

- Cesare Pavese (1908–1950): Italian poet, novelist, literary critic and translator.[232]

- Edmund Penning-Rowsell (1913–2002): British wine writer, considered the foremost of his generation.[233]

- Calel Perechodnik (1916–1943): Polish Jewish diarist and Jewish Ghetto policeman at the Warsaw Ghetto.[234]

- Melissa Holbrook Pierson: American essayist and author of The Perfect Vehicle and other books.[235]

- Harold Pinter (1930–2008): Nobel Prize-winning English playwright, screenwriter, director and actor. One of the most influential modern British dramatists, his writing career spanned more than 50 years.[236]

- Luigi Pirandello (1867–1936): Italian dramatist, novelist, and short story writer awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1934.[237]

- Fiona Pitt-Kethley (born 1954): British poet, novelist, travel writer and journalist.[238]

- Neal Pollack (born 1970): American satirist, novelist, short story writer, and journalist.[239]

- Terry Pratchett (1948–2015): English fantasy author known for his satirical Discworld series.[240]

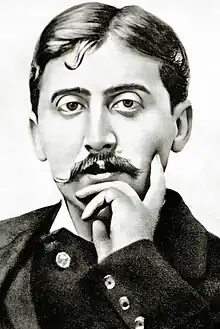

- Marcel Proust (1871–1922): French novelist, critic, and essayist. Best known for his work, In Search of Lost Time.[241][242]

- Kate Pullinger (born before 1988): Canadian-born novelist and author of digital fiction.[243]

- Philip Pullman CBE (born 1946): British author of the His Dark Materials fantasy trilogy for young adults, which has atheism as a major theme, calls himself an atheist,[244][245] though he also describes himself as technically an agnostic.[246]

- François Rabelais, (c. 1494 – 9 April 1553): French novelist sometimes regarded as an atheist[247] but more often as a Christian humanist[248]

- Craig Raine (born 1944): English poet and critic, the best-known exponent of Martian poetry.[249]

- Ayn Rand (1905–1982): Russian-born American author and founder of Objectivism.[250]

- Derek Raymond (1931–1994): English writer, credited with being the founder of English noir.[251]

- Stan Rice (1942–2006): American poet and artist, Professor of English and Creative Writing at San Francisco State University, and husband of writer Anne Rice.[252]

- Joseph Ritson, (1752–1803): English author and antiquary, friend of Sir Walter Scott.[253]

- Michael Rosen (born 1946): English children's novelist, poet and broadcaster, Children's Laureate 2007–2009.[254]

- Alex Rosenberg (born 1946): Philosopher of science, author of The Atheist's Guide to Reality,[255]

- Philip Roth (1933–2018): American novelist. Known for his novella, Goodbye, Columbus.[256]

- Salman Rushdie (born 1947): British Indian author, notable for The Satanic Verses and Midnight's Children.[257][258][259]

S–Z

- José Saramago (1922–2010): Portuguese writer, playwright and journalist. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1998.[260][261]

- Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980): French existentialist philosopher and playwright, 1964 Nobel Prize in literature that he refused. His mother was a first cousin of Albert Schweitzer. His lifelong companion was feminist Simone de Beauvoir (1908–1986).

- Dan Savage (born 1964): Author and sex advice columnist.[262] Despite his atheism, Savage considers himself Catholic "in a cultural sense."[263]

- Bernard Schweizer (born 1962): English professor and critic specializing in literary manifestations of religious rebellion. Schweizer reintroduced the forgotten term misotheism (hatred of God) in his most recent book Hating God: The Untold Story of Misotheism, Oxford University Press, 2010. Schweizer, who has published several books on literature, is not a misotheist but a secular humanist.[264]

- Maurice Sendak (1928–2012): American writer and illustrator of children's literature.[265]

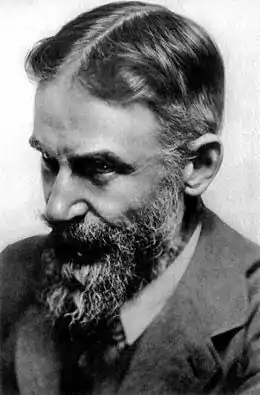

- George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950): Irish playwright and cofounder of the London School of Economics. He is the only person to have won both a Nobel Prize in Literature (1925) and an Oscar, respectively, for his contributions to literature and for his work on the film Pygmalion (1938, adapted from his play of the same name).[266][267][268]

- Francis Sheehy-Skeffington (1878–1916): Irish suffragist, pacifist and writer.[269]

- Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822): English Romantic poet and author of the philosophical essay The Necessity of Atheism.[270][271]

- Michael Shermer (born 1954): Science writer and editor of Skeptic magazine. Has stated that he is an atheist, but prefers to be called a skeptic.[272]

- Claude Simon (1913–2005): French novelist and the 1985 Nobel Laureate in Literature.[273]

- Joan Smith (born 1953): English journalist, human rights activist and novelist.[274]

- Warren Allen Smith (1921–2017): Author of Who's Who in Hell.[275]

- Wole Soyinka (born 1934): Nigerian writer, poet and playwright. He was awarded the 1986 Nobel Prize in Literature.[276]

- David Ramsay Steele (born before 1968): Author of Atheism Explained: From Folly to Philosophy.[277]

- G. W. Steevens (1869–1900): British journalist and writer.[278]

- Bruce Sterling (born 1954): American science fiction author, best known for his novels and his seminal work on the Mirrorshades anthology, which helped define the cyberpunk genre.[279]

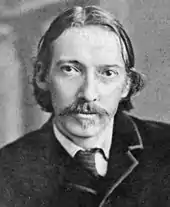

- Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894): Scottish novelist, poet and travel writer, known for his works Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.[280]

- André Suarès (1868–1948): French poet and critic.[281]

- Italo Svevo (1861–1928): Italian writer and businessman, author of novels, plays, and short stories.[282]

- Vladimir Tendryakov (1923–1984): Russian short-story writer and novelist.[283]

- Tiffany Thayer (1902–1959): American author, advertising copywriter, actor and founder of the Fortean Society.[284]

- Paul-Henri Thiry (1723–1789): Baron d'Holbach was a French-German author, philosopher, encyclopedist and a prominent figure in the French Enlightenment.[285]

- James Thomson ('B.V.') (1834–1882): British poet and satirist, famous primarily for the long poem The City of Dreadful Night (1874).[286]

- Miguel Torga (1907–1995): Portuguese author of poetry, short stories, theatre and a 16 volume diary, one of the greatest Portuguese writers of the 20th century.[287]

- Sue Townsend (1946–2014): British novelist, best known as the author of the Adrian Mole series of books.[288]

- Freda Utley (1898–1978): English scholar, best-selling author and political activist.[289]

- Giovanni Verga (1840–1922): Italian realist (Verismo) writer.[290]

- Frances Vernon (1963–1991): British novelist.[291]

- Gore Vidal (1925–2012): American author, playwright, essayist, screenwriter, and political activist. His third novel, The City and the Pillar (1948), outraged mainstream critics as one of the first major American novels to feature unambiguous homosexuality. He also ran for political office twice and was a longtime political critic.[292]

- Kurt Vonnegut (1922–2007): American author, writer of Cat's Cradle, among other books. Vonnegut said "I am an atheist (or at best a Unitarian who winds up in churches quite a lot)."[49]

- Sarah Vowell (born 1969): American author, journalist, humorist, and commentator, and a regular contributor to the radio program This American Life.[293]

- Ethel Lilian Voynich (1864–1960): Irish-born novelist and musician, and a supporter of several revolutionary causes.[294]

- Marina Warner CBE, FBA (born 1946): British novelist, short story writer, historian and mythographer, known for her many non-fiction books relating to feminism and myth.[295]

- Ibn Warraq, known for his books critical of Islam.[296]

- H.G. Wells (1866–1946): Distanced himself from Christianity, later from theism, and ended an atheist.[297]

- Edmund White (born 1940): American novelist, short-story writer and critic.[298]

- Sean Williams (born 1967): Australian science fiction author, a multiple recipient of both the Ditmar and Aurealis Awards.[299]

- Simon Winchester OBE (born 1944): British author and journalist.[300]

- Tom Wolfe (1930–2018): Noted author and member of 'New Journalism' school[301]

- Leonard Woolf (1880–1969): Noted British political theorist, author, publisher, and civil servant, husband of author Virginia Woolf.[302]

- Virginia Woolf (1882–1941): English author, essayist, publisher, and writer. She is regarded as one of the foremost modernist literary figures of the twentieth century.[303]

- Gao Xingjian (born 1940): Chinese émigré novelist, dramatist, critic, translator, stage director and painter. Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2000.[304]

- David Yallop (1937–2018): British author. British true crime author.[305]

Journalists

Professional journalists, known to be atheists:

A–L

- David Aaronovitch (born 1954): British journalist, author and broadcaster.[306][307]

- Amy Alkon (born 1964): American advice columnist known as the Advice Goddess, author of Ask the Advice Goddess, published in more than 100 newspapers within North America.[308]

- Lynn Barber (born 1944): British journalist, best known as an interviewer.[309]

- Paul Barker (1935–2019): English journalist and writer.[310]

- Richard Boston (1938–2006): English journalist and author, dissenter and pacifist.[311]

- Anna Blundy (born 1970): British journalist and author.[312]

- Jason Burke (born 1970): British journalist, chief foreign correspondent of The Observer.[313]

- Chandler Burr (born 1963): American journalist and author, currently the perfume critic for The New York Times.[314]

- Michael Bywater (born 1953): British writer and broadcaster.[315]

- Nick Cohen (born 1961): British journalist, author, and political commentator.[316]

- Boris Dežulović (1964–): Croatian journalist, writer and columnist, best known as one of the founders of the now defunct satirical magazine Feral Tribune.

- John Diamond (1953–2001): British broadcaster and journalist, remembered for his column chronicling his fight with cancer.[317][318]

- Robert Fisk (1946–2020): British journalist, Middle East correspondent for The Independent, "probably the most famous foreign correspondent in Britain" according to The New York Times.[319]

- Paul Foot (1937–2004): British investigative journalist, political campaigner, author, and long-time member of the Socialist Workers Party.[320]

- Masha Gessen (born 1967): Russian journalist and author.[321]

- Linda Grant (born 1951): British journalist and novelist.[322]

- Muriel Gray (born 1958): Scottish journalist, novelist and broadcaster.[323]

- John Harris (born 1969): British journalist, writer, and critic.[324]

- Simon Heffer (born 1960): British journalist and writer.[325]

- Anthony Holden (born 1947): British journalist, broadcaster and writer, especially of biographies.[326]

- Mick Hume (born 1959): British journalist – columnist for The (London) Times and editor of Spiked. Described himself as "a longstanding atheist", but criticised the 'New Atheism' of Richard Dawkins and co.[327]

- Tom Humphries (born before 2002): English-born Irish sportswriter and columnist for The Irish Times.[328]

- Simon Jenkins (born 1943): British journalist, newspaper editor, and author. A former editor of The Times newspaper, he received a knighthood for services to journalism in the 2004 New Year honours.[329]

- Oliver Kamm (born 1963): British writer and newspaper columnist, a leader writer for The Times.[330]

- Terry Lane (born 1943): Australian radio broadcaster and newspaper columnist.[331]

- Dominic Lawson (born 1956): British journalist, former editor of The Spectator magazine.[332]

- Magnus Linklater (born 1942): Scottish journalist and former newspaper editor.[333]

M–Z

- Padraic McGuinness AO (1938–2008): Australian journalist, activist, and commentator.[334]

- Gareth McLean (born c.1975): Scottish journalist, writer for The Guardian and Radio Times, shortlisted for the Young Journalist of the Year Award at the British Press Awards in 1997 and 1998.[335]

- Heather Mallick (born 1959): Canadian columnist, author and lecturer.[336]

- Andrew Marr (born 1959): Scottish journalist and political commentator.[337]

- Jules Marshall (born 1962): English-born journalist and editor.[338]

- Jonathan Meades (born 1947): English writer and broadcaster on food, architecture and culture.[339]

- H. L. Mencken (September 12, 1880 – January 29, 1956): American journalist, essayist, magazine editor, satirist, critic of American life and culture, and a scholar of American English. As a nationally syndicated columnist and book author, he famously spoke out against Christian Science, social stigma, fakery, Christian radicalism, religious belief (and as a fervent nonbeliever the very notion of a Deity), osteopathy, antievolutionism, chiropractic, and the "Booboisie", his word for the ignorant middle classes.

- Stephanie Merritt (born 1974): British critic and feature writer for a range of newspapers, Deputy Literary Editor at The Observer since 1998.[340]

- Martin O'Hagan (1950–2001): Northern Irish journalist, the most prominent journalist to be assassinated during the Troubles.[341]

- Deborah Orr (1962–2019): British journalist and broadcaster.[342]

- Ruth Picardie (1964–1997): British journalist and editor, noted for her memoir of living with breast cancer, Before I Say Goodbye.[343]

- Claire Rayner OBE (1931–2010): British journalist best known for her role for many years as an agony aunt.[344]

- Jay Rayner (born 1966): British journalist, writer and broadcaster.[345]

- Ron Reagan (born 1958): American magazine journalist, board member of the politically activist Creative Coalition, son of former U. S. President Ronald Reagan.[346]

- Henric Sanielevici (1875–1951): Romanian journalist and literary critic, also remembered for his work in anthropology, ethnography, sociology and zoology.[347][348]

- Ariane Sherine (born 1980): British comedy writer, journalist and creator of the Atheist Bus Campaign.[349]

- Jill Singer (1957–2017): Australian journalist, columnist and television presenter.[350]

- Matt Taibbi (born 1970): American journalist and political writer, currently working at Rolling Stone (note: he calls himself an agnostic/atheist).[351]

- Jeffrey Tayler (born 1970): American author and journalist, the Russia correspondent for The Atlantic Monthly.[352]

- Nicholas Tomalin (1931–1973): British journalist and writer, one of the top 40 journalists of the modern era.[353]

- Bill Thompson (born 1960): English technology writer, best known for his weekly column in the Technology section of BBC News Online and his appearances on Digital Planet, a radio show on the BBC World Service.[354]

- Jerzy Urban (born 1933): Polish journalist, commentator, writer and politician, editor-in-chief of the weekly Nie and owner of the company which owns it, Urma.[355]

- Gene Weingarten (born 1951): American humor writer and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist.[356]

- Francis Wheen (born 1957): British journalist, writer and broadcaster.[357]

- Peter Wilby (born 1944): British journalist, former editor of The Independent on Sunday and New Statesman.[358]

- Adrian Wooldridge (born before 1984): British journalist, Washington Bureau Chief and 'Lexington' columnist for The Economist magazine.[359]

Notes

- Sims, Chris (December 3, 2012). "War Rocket Ajax #138: Jason Aaron Talks 'Thor: God Of Thunder'" Archived 2013-08-25 at the Wayback Machine. ComicsAlliance.

- Ackerman, Forrest J.; Linaweaver, Brad (2004). Worlds of Tomorrow: The Amazing Universe of Science-fiction Art. Collectors Press, Inc. p. 12. ISBN 9781888054934.

He was Uncle Forry. He made a career out of understanding that the eye is the window to the soul. He was the atheist with a sense of wonder and a love of childhood. He felt the same emotions as deeply religious and sentimental people, which was an unusual quality for the true materialist.

- "I am a radical Atheist..." Adams in an interview by American Atheists .

- Spirituality, Halo or Hoax Archived 2012-01-01 at the Wayback Machine – Javedakhtar.com, Spirituality, Halo or Hoax, 26 February 2005. "There are certain things that I would like to make very clear at the very outset. Don't get carried away by my name – Javed Akhtar. I am not revealing a secret, I am saying something that I have said many times, in writing or on TV, in public ... I am an atheist, I have no religious beliefs. And obviously I don't believe in spirituality of some kind. Some kind. "NDIA Today Conclave – February 26, 2005", retrieved April 4, 2012

- "Ben Allah'a inanmam, ben öldüğümde cesedimi yakın, küllerimi savurun. (Eng. I don't believe in God, when I die, burn my remains and scatter my ashes.)

- "It is well known that I am not a religious person, I grew up and remain an atheist". Tariq Ali, Interview: Tariq Ali Archived 2007-07-03 at the Wayback Machine, Socialist Review November 2006 (accessed April 22, 2008).

- Amado is described as an "ateu convicto", or "convinced atheist". Menezes, Cynara (August 8, 2001). "Velório de Jorge Amado foi discreto" (in Portuguese). Folha de S. Paulo. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- "Once, filming in Italy with the American director John Huston and a US army crew, Ambler and his colleagues were shelled so fiercely that his unconscious 'played a nasty trick on him' (Ambler, Here Lies, 208). A confirmed atheist, he heard himself saying, 'Into thy hands I commend my spirit.' " Michael Barber: 'Ambler, Eric Clifford (1909–1998)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edition, January 2007 (accessed April 29, 2008).

- "His son Martin, who led the ceremony, said: 'His relationship with the Christian God was not entirely frictionless.' In 1962 (the Russian poet) Yevtushenko asked him 'Are you an atheist?' He replied: 'Well, yes – but it's more that I hate Him.' ", John Ezard, "Secular send-off for an 'old devil' who did not wans too much fuss over his funeral", The Guardian (London), October 23, 1996, p. 8.

- Prothero, Donald R (27 August 2014). "The Thinking Atheist Confesses". ESkeptic. The Skeptics Society. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- Prothero, Donald (9 February 2016). "ALL SACRED COWS". eSkeptic. The Skeptics Society. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- On Moyers and Company, 6 July 2012, Appleman described himself as "not just an atheist but a humanist."

- "Artaud's theories are phrased in a strongly poetical language that betrays an acute awareness of modernity's disenchanted life-world, but, at the same time, is obsessed with reviving the supernatural. His profoundly atheist religiosity (if we may call it so) obviously presents great problems to scholarship." Thomas Crombez: Dismemberment in Drama/Dismemberment of Drama – Chapter Two – The Dismembered Body in Antonin Artaud's Surrealist Plays. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-01. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Archived 2013-09-03 at the Wayback Machine - "I am an atheist, out and out. It took me a long time to say it... I don't have the evidence to prove that God doesn't exist, but I so strongly suspect he doesn't that I don't want to waste my time." Isaac Asimov in "Free Inquiry", Spring 1982, vol.2 no.2, p. 9 (See Wikiquote.)

- "Last week, looking through a book about 15th-century painting in Italy, I began to wonder why I loved these paintings so much. Almost all of them are illustrations of religious subjects, and I have been an atheist almost since the day I was confirmed in the Christian faith by the Bishop of Norwich in 1931. To describe the atheism first: it originated in a certainty that I was going to start breaking the rules as laid down by the god I'd been taught about, followed by a suspicion that if his rules were so easy to break he couldn't be all that he was cracked up to be. Then came its firmer base: the observation that many of the most hideous things done to each other by human beings have been done in his name. It can be argued that this is our fault, not God's. But the god we Europeans are supposed to believe in a) created us as well as everything else that is; b) is omnipotent; c) is Love. In which case, one must assume from the evidence rammed down our throats for century after century that he is liable to fits of serious derangement during which he is Not Himself." Diana Athill, 'I'm a believer – but only in a good story', The Guardian, January 21, 2004, Features Pages, p. 5.

- "Rather than tackle Baldwin's atheist stance, Malcolm found a point of departure on the question of identity, stating that he was "proud to be a black man."" Herb Boyd, Baldwin's Harlem: a biography of James Baldwin (2008), page 75.

- Welch, Frances. "All Praise and Glory to the Mind of Man".

Ballard confesses to being an atheist, but adds: "that said, I'm extremely interested in religion... I see religion as a key to all sorts of mysteries that surround the human consciousness."

- "I'm an evangelical atheist so I'm not into supernatural effects – I hated The Exorcist – but John Carpenter's remake of The Thing is different." "I was a brain-eating zombie... As the scary season descends ... famous horror experts choose their most terrifying screen experiences", The Daily Telegraph, October 30, 2004, Arts p. 4.

- Stroev, Alexandre (2021). "HENRI BARBUSSE ENTRE JÉSUS ET STALINE". Revue d'Histoire littéraire de la France. 121 (2): 361–374. ISSN 0035-2411. JSTOR 27012635.

- "Maclean's interview: Julian Barnes". Maclean. October 29, 2008. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

Writer Julian Barnes talks to Kenneth Whyte about his atheism and saints, his parents and what makes for a best death.

- Huberman, Jack (2007). The Quotable Atheist. Nation Books. p. 31. ISBN 9781560259695.

- Thurman, Judith. Introduction to Simone de Beauvoir's The Second Sex. Excerpt published in The New York Times 27 May 2010. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- "Evil and Me", Benford; in 50 Voices of Disbelief: Why We Are Atheists, ed. Russell Blackford and Udo Schuklenk, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, pp. 157-60.

- Once Forbidden, Now Championed; Toni Bentley, a former ballerina, is the author of The Surrender by Charles McGrath, October 15, 2004, The New York Times

- Toni Bentley Archived 2014-11-04 at the Wayback Machine Biography webpage

- "Berton's book, The Comfortable Pew, in which as a lifelong atheist he attacked status quo religiosity, outraged churchgoers. But the wider public came to expect to be challenged by Berton's views." Cathryn Atkinson, 'Obituary: Pierre Berton', The Guardian, December 7, 2004, p. 27.

- Besant, Annie (May 2012). My Path to Atheism. ISBN 978-1406878363.

- "Wilfred Scawen Blunt was notorious as an atheist, a libertine, an adventurer and a poet. Somehow he also found time to be a diplomat – one of the earliest in this country to make a real attempt to understand Islam – and an anti-imperialist, becoming the first British-born person to go to jail for Irish independence." Phil Daoust, The Guardian, March 11, 2008, G2: Radio: Pick of the day, p. 32.

- " "What song would you like played at your funeral?" "We'll Meet Again. I'd like the congregation to join in. As a devout atheist, I should make it clear there are no religious connotations." " Rosanna Greenstreet, 'Q&A: William Boyd', The Guardian, February 3, 2007, Weekend Pages, p. 8.

- Bradlaugh, Charles (2004). Encyclopedia of World Biography. Retrieved March 28, 2015.

- "Passionate and enthusiastic, Lily was converted to atheism, pacifism, and feminism by Georg von Gizycki, whom she married in 1893." 'Braun, Lily', Encyclopædia Britannica Online (accessed August 1, 2008).

- Lyon, James K.; Breuer, Hans-Peter, eds. (1995). Brecht Unbound. University of Delaware Press. p. 120. ISBN 9780874135374.

With Stravinsky and Brecht we are juxtaposing an avowedly apolitical artist, rather reactionary in most phases of his life, and a practicing Russian Orthodox with a Marxist and atheist.

- Reviewing a production of The Romans in Britain, Charles Spencer wrote: "It strikes me as an exceptionally powerful study of the human need for belief in a higher power, notwithstanding the fact that Brenton himself is an atheist. And the dramatist examines the nature of Paul's faith with both sympathy and insight." 'A powerful and thrilling act of heresy', The Daily Telegraph, November 10, 2005, Reviews, p. 30.

- Reviewing Mark Polizzotti's Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton Douglas F. Smith called him, "[a] cynical atheist, the poet, critic, and artist harbored an irrepressible streak of romanticism."

- "To speak of God, to think of God, is in every respect to show what one is made of.... I have always wagered against God and I regard the little that I have won in this world as simply the outcome of this bet. However paltry may have been the stake (my life) I am conscious of having won to the full. Everything that is doddering, squint-eyed, vile, polluted and grotesque is summoned up for me in that one word: God!" – André Breton, taking from a footnote from his book, Surrealism and Painting. Quotations by the poet: Andre Breton

- Gilson, Étienne (1988). Linguistics and philosophy: an essay on the philosophical constants of language. University of Notre Dame Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-268-01284-7.

Breton professed to be an atheist...

- Browder, Clifford (1967). André Breton: Arbiter of Surrealism. Droz. p. 133.

Again, the atheist Breton's predilection for ideas of blasphemy and profanation, as well as for the " demonic " word noir, contained a hint of Satanism and alliance with infernal powers.

- "It [her non-fiction book Black Ship to Hell (1962)] endeavoured to formulate a morality based on reason rather than religion – Brophy described herself as 'a natural, logical and happy atheist' (King of a Rainy Country, afterword, 276)." Peter Parker: 'Brophy, Brigid Antonia [married name Brigid Antonia Levey, Lady Levey] (1929–1995)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edition, May 2006 (accessed April 29, 2008).

- Reviewing Brownjohn's Collected Poems, Anthony Thwaite wrote: "Brownjohn is 75 at the moment of publication. He has been on the literary scene – publishing, reviewing, judging, chairing, tutoring, giving readings – since the 1950s. He has also been a London borough councillor, a Labour parliamentary candidate (Richmond, Surrey, 1964), very much what I think of as decent, persistent, dogged "Old Labour" – sensitive but solid, inclining towards the puritan (though a self-confessed atheist in matters of religion) – and a strenuous campaigner for serious radio and television, anti-muzak, anti-destruction of libraries, for the proper traditional cultural concerns of the British Council, et al." 'Poetry: The vodka in the verse', The Guardian, October 7, 2006, Review Pages, p. 18

- "For those who believe in God, most of the big questions are answered. But for those of us who can't readily accept the God formula, the big answers don't remain stone-written. We adjust to new conditions and discoveries. We are pliable. Love need not be a command or faith a dictum. I am my own God. We are here to unlearn the teachings of the church, state and our education system. We are here to drink beer. We are here to kill war. We are here to laugh at the odds and live our lives so well that Death will tremble to take us."--Charles Bukowski, Life (magazine), December 1988, quoted from James A. Haught, ed, 2000 Years of Disbelief.

- Barker, Dan (2011). The Good Atheist: Living a Purpose-Filled Life Without God. Ulysses Press. p. 170. ISBN 9781569758465.

An essayist who popularized the American romantic view of nature, Burroughs wrote, "When I look up at the starry heavens at night and reflect upon what is it that I really see there, I am constrained to say, 'There is no God.'" In his 1910 journal, he wrote: "Joy in the universe, and keen curiosity about it all-that has been my religion."

- Bush describes himself as "an atheist who has nevertheless worked intimately in Jewish religious institutions as a writer and editor for much of my adult life." The rabbi and the atheist Archived 2012-02-07 at the Wayback Machine, New Jersey Jewish News, September 20, 2007 (accessed 21 April 2008).

- "By this time she had become an atheist and socialist." Nathalie Blondel: 'Butts, Mary Franeis (1890–1937)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 (accessed April 30, 2008).

- "Though an atheist, Cabral had a deep, atavistic fear of the devil. When his wife died in 1986, he placed an emblem of Our Lady of Carmen around her neck, saying, in his mocking way, that this would make sure that she went directly to heaven, without being stopped at customs." 'Joao Cabral: His poetry voiced the sufferings of Brazil's poor', The Guardian, October 18, 1999, Leader Pages; p. 18.

- He stated in a 1936 lecture to Harvard Divinity School students: "Most students ... wish to know whether I believe in the existence of God or in immortality, and if so why. They regard it impossible to leave these matters unsettled – or at least extremely detrimental to religion not to have the basis of such conviction. Now for my part I do not find it impossible to leave them open.... I can describe myself as no ardent theist or atheist." – Henry Cadbury, "My Personal Religion", republished on the Quaker Universalist Fellowship website.

- Cf. "Political Autobiography of a Young Man" and "Objective Biographical Notice" in Hermit in Paris, 133, 162

- Malmont, Paul (2011). The Astounding, the Amazing, and the Unknown: A Novel. Simon and Schuster. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4391-6893-6.

For, even though John W. Campbell was an avowed atheist, when the most powerful ed at Street & Smith lost his temper, he put the fear of God into others.

- David Simpson writes that Camus affirmed "a defiantly atheistic creed." Albert Camus (1913–1960), The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2006, (Accessed June 14, 2007).

- Haught, James A. (1996). 2,000 Years of Disbelief: Famous People with the Courage to Doubt. Prometheus Books. pp. 261–262. ISBN 1-57392-067-3.

- Biagini, Mario, Giosuè Carducci, Mursia, 1976, p. 208.

- "All the mythic versions of women, from the myth of the redeeming purity of the virgin to that of the healing, reconciling mother, are consolatory nonsenses; and consolatory nonsense seems to me a fair definition of myth, anyway. Mother goddesses are just as silly a notion as father gods. If a revival of the myths of these cults gives women emotional satisfaction, it does so at the price of obscuring the real conditions of life. This is why they were invented in the first place." Angela Carter, The Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography (1978) p. 5

- Chekhov, Anton Pavlovich; Karlinsky, Simon; Heim, Michael Henry (1997). Karlinsky, Simon (ed.). Anton Chekhov's Life and Thought: Selected Letters and Commentary. Northwestern University Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780810114609.

While Anton did not turn into the kind of militant atheist that his older brother Alexander eventually became, there is no doubt that he was a nonbeliever in the last decades of his life.

- Tabachnikova, Olga (2010). Anton Chekhov Through the Eyes of Russian Thinkers: Vasilii Rozanov, Dmitrii Merezhkovskii and Lev Shestov. Anthem Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-84331-841-5.

For Rozanov, Chekhov represents a concluding stage of classical Russian literature at the turn of the centuries, caused by the 'fading' of a thousand' years old Christian tradition which was spiritually feeding this literature. On the one hand, Rozanov regards Chekhov's positivism and atheism as his shortcomings, naming them amongst the reasons of Chekhov's popularity in society.

- Pevear, Richard (2009). Selected Stories of Anton Chekov. Random House Digital, Inc. pp. xxii. ISBN 9780307568281.

'In his revelation of those evangelical elements,' writes Leonid Grossman, 'the atheist Chekhov is unquestionably one of the most Christian poets of world literature.'

- Narayan, Kirin (2012). Alive in the Writing: Crafting Ethnography in the Company of Chekhov. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226567921.

Though Chekhov considered himself an atheist – partly in response to his tyrannically religious father – his childhood familiarity with the rituals and stories of the Russian Orthodox Church pervades many of his stories.

- "Roadtrip Nation", PBS.

- "Greta Christina". Greta Christina. Archived from the original on 2018-10-07. Retrieved 2011-09-01.

- "Greta Christina | Secular Student Alliance: Atheists, Humanists, Agnostics & Others". Secularstudents.org. 2009-12-20. Archived from the original on 2011-09-03. Retrieved 2011-09-01.

- "...Stanley [Kubrick] is a Jew and I'm an atheist". Clarke quoted in Jeromy Agel (Ed.) (1970). The Making of Kubrick's 2001: p. 306

- "We can only guess what Clodd would have thought of having an evangelical preacher owning his old house: he was a noted atheist, who rejected his parents' ambition for him to become a Baptist minister in favour of becoming chairman of the Rationalist Press Association. His contribution to literature was in popularising the work of Charles Darwin and other evolutionary scientists in the face of opposition from the church. "The story of creation", wrote Clodd, " is the story of gas into genius"." Rose Gibbs, 'A religious conversion', The Sunday Telegraph, August 14, 2005, Section: House & Home, p. 4.

- In his fictionalized autobiography Boyhood: Scenes from Provincial Life (1997), Coatzee writes of himself: "Though he himself is an atheist and has always been one, he feels he understands Jesus better" than his religious teacher does. Adam Kirsch, "With Fear and Trembling: The essential Prostestantism of J. M. Coetzee's late fiction", The Nation, vol. 304, no. 18 (June 19/26, 2017), p. 38. The whole review article: pp. 37–38, 40.

- "For one whose life had been so full of ironies, it was fitting that five priests celebrated a requiem mass for him in Youghal, although he had been a committed atheist." Richard Ingrams: 'Cockburn, (Francis) Claud (1904–1981), rev. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, May 2006 (accessed April 30, 2008).

- "An unlikely friendship developed between Reckitt and G. D. H. Cole. Although an unapproachable cold atheist, and at root an anarchist, Cole joined forces with Reckitt, the clubbable, romantic medievalist, archetypal bourgeois, and unswerving Anglican with a dogmatic faith, to found the National Guilds League in 1915." J. S. Peart-Binns, 'Reckitt, Maurice Benington (1888–1980)', rev., Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 (accessed May 2, 2008).

- "Like Margaret Jourdain, and most of her characters who are not fools or knaves, Ivy Compton-Burnett was a firm atheist, dismissing religion because 'No good can come of it' (Spurling, Ivy when Young, 77)." Patrick Lyons: 'Burnett, Dame Ivy Compton- (1884–1969)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 (accessed April 30, 2008).

- " 'Don't stand any nonsense from the Astors,' Sitwell concluded: prophetic advice, for within a short time of his arrival, Lord Astor was writing to the new literary editor to say that reviewers must combine 'ability and character and high ideals': he was especially worried in case A.L. Rowse proved a 'militant atheist', for 'I am convinced that our great influence in the world is because this country has given a definite place to religion and to free religion, ie Protestantism at that.' Undaunted, Connolly made it plain in his reply that he would not put up with such nonsense: he himself was an atheist, and discerned no difference in behaviour between an English Protestant and an English atheist." Jeremy Lewis, 'Wine, Women, £800 a Year: Nice One, Cyril', The Observer, April 13, 1997, The Observer Review Pages, p. 1.

- "Like [Joseph] Conrad, [his wife] Jessie was nominally a Catholic but actually an atheist." Jeffrey Meyers, Joseph Conrad: a Biography, New York, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1991, ISBN 0-684-19230-6, p. 139.

- "I'm an atheist. God is an abstract noun, he's not a Father Christmas up there in Heaven, he's an abstract bloody noun who has been exploited by men in order to exploit other men, through the centuries." Edmund Cooper, We must love one another or die: an interview with Edmund Cooper Archived 2008-05-29 at the Wayback Machine (pdf), c. 1973.

- 'Cooper' was the pen name of Harry Hoff. "As a militant atheist he was especially on his guard in churches, and at the wedding of a much younger friend had to be restrained from heckling the bride's clerical uncle, who was delivering an address." D. J. Taylor, 'Hoff, Harry Summerfield (1910–2002)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edn, Oxford University Press, January 2006 (accessed May 1, 2008).

- "The impulse of this book came when I was writing Quarantine. At the end of writing that book, I was no less of an atheist than I was before, yet it did make me think about my atheism. Thinking about the bleakness of my own atheism, and the inadequacy of the old fashioned kind of atheism when the big events of life – especially death – came along, made me want to see whether I could come up with a narrative of comfort, a false narrative of comfort, but one that could match the narratives of comfort religions come up with to get you through death and bereavement." Jim Crace, Beatrice Interview: Jim Crace, c. 1999 (accessed April 28, 2008).

- Criticising the 'New Atheists' (Harris, Hitchens, Dawkins, Onfray, Grayling and co.), Dalrymple wrote: "Yet with the possible exception of Dennett's [book Breaking the Spell], they advance no argument that I, the village atheist, could not have made by the age of 14 (Saint Anselm's ontological argument for God's existence gave me the greatest difficulty, but I had taken Hume to heart on the weakness of the argument from design)." What the New Atheists Don't See, City Journal, Autumn 2007 (accessed April 24, 2008).

- Chattopadhyay, Debiprasad (1994). "FOUR CALCUTTANS IN DEFENCE OF SCIENTIFIC TEMPER" (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science. p. 112. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 November 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

As contrasted with Bacon, however, Datta's enthusiasm for natural science ultimately led him to become a stark atheist going to the extent of disproving the efficacy of prayer with an ingenious arguments,...

- "As a boy he attended a nonconformist chapel, and later an Anglican church, but in later life was to declare himself an atheist." Meic Stephens: 'Davies, Rhys (1901–1978)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 (accessed April 30, 2008).

- "Davison died on May 24, 1970 at Greensborough, Melbourne; a lifelong atheist, he was cremated after a secular funeral." Robert Darby, 'Davison, Frank Dalby (1893–1970)', Australian Dictionary of Biography Online Edition (accessed July 16, 2008).

- Alain de Botton told interviewer Chris Hedges, "I'm an atheist." C-SPAN 2 "After Words" interview, 31 March 2012.

- D'Souza, Dinesh, What's so great about Christianity, Regnery Publishing, 2007, p. 22.

- "De Sade overcame his boredom and anger in prison by writing sexually graphic novels and plays. In July 1782 he finished his Dialogue entre un prêtre et un moribond (Dialogue Between a Priest and a Dying Man), in which he declared himself an atheist." 'Sade, Marquis de.' Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online (accessed August 1, 2008).

- "He rejected his father's ambition to make him a rabbi. Instead he became an atheist and, following in the footsteps of Marx, Trotsky, and his countrywoman Rosa Luxemburg, a lifelong 'non-Jewish Jew' (Non-Jewish Jew, ed. Deutscher)." John McIlroy: 'Deutscher, Isaac (1907–1967)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 (accessed April 30, 2008).

- "Friends said Disch had been despondent over ill health and Naylor's death in 2005. Yet he seemed in good humor for a brief Publishers Weekly interview last spring about his most recent book, The Word of God. An outspoken atheist, Disch adopted the deity's perspective to score points on the absurdity of hell and similar numinous postulates. 'One of the wonderful things about being God is you can say such nonsense and it's all true,' he said." Stephen Miller, "Thomas M. Disch, 68, Eclectic Writer of Science Fiction", The New York Sun, July 8, 2008, Obituaries, p. 6.

- Linati, Carlo, Dossi, Garzanti, Milano, 1944, p. 452.

- "He does appreciate the new and confident pluralism that has loosened the grip of the Roman Catholic hierarchy on education. His three children attend secular state schools, and he welcomes the widening 'rift between Church and state. It has happened, it is happening, and for me that's a great thing. As an atheist, I feel very comfortable in Ireland now.'" Boyd Tonkin interviewing Doyle, The Independent (London), September 17, 2004, Features, pp. 20–21.

- Cowie, Alexander, Alfred Kazin, and Charles Shapiro. "The Stature of Theodore Dreiser: A Critical Survey of the Man and His Work." American Literature 28.2 (1956): 244. Web. "he turned against his father's orthodox religion and became an atheist."

- "But the 21st century has done nothing to prevent two others from the Manchester area from reshaping and modernising the Christmas story -the poet Carol Ann Duffy and the composer Sasha Johnson Manning, who have written 16 new carols. Duffy, brought up a Catholic, pronounces herself an atheist; Johnson Manning is a committed Christian." Geoff Brown, 'O great big town of Manchester', The Times, December 7, 2007, Times2; p. 15.

- "Turan Dursun, a former imam and an atheist writer..." A dark shadow over Turkey Archived 2008-06-04 at the Wayback Machine, Turkish Daily News, January 20, 2007 (accessed April 15, 2008)

- "It was also a sign that, though Eagleton is now an atheist, he has not entirely shaken off his religious upbringing. "I attacked Dawkins's book on God because I think he is theologically illiterate. I value my Catholic background very much. It taught me not to be afraid of rigorous thought, for one thing." But it is also because, he insists, Marxism offers the blueprint for a moral society." Paul Vallely, 'Class warrior; The Saturday Profile: Terry Eagleton', The Independent (London), October 13, 2007, p. 42.

- "A Resounding Eco", Time, June 13, 2005, archived from the original on October 15, 2007,

His new book touches on politics, but also on faith. Raised Catholic, Eco has long since left the church. 'Even though I'm still in love with that world, I stopped believing in God in my 20s after my doctoral studies on St. Thomas Aquinas. You could say he miraculously cured me of my faith,...'

- "Tariq likes permanent revolution, whereas I am a libertarian conservative. True, we are both atheists, but Tariq is evangelical while I am benign about religion and think the Throne should be occupied by a member of the Church of England." Ruth Dudley-Edwards, 'Will half of Ireland really back Cameroon? How will a win affect public sentiment? Or a defeat?', The Daily Telegraph, June 1, 2002, p. 24.

- "I was raised as a Christian, and I still retain a lot of the values of Christianity. The trouble with basing values on religions, though, is that the premises of most of them are pure wishful thinking; you either have to refuse to scrutinise those premises – take them on faith, declare that they "transcend logic" – or reject them. As Paul Davies has said, most Christian theologians have retreated from all the things that their religion supposedly asserts; they take a much more "modern" view than the average believer. But by the time you've "modernised" something like Christianity – starting off with "Genesis was all just poetry" and ending up with "Well, of course there's no such thing as a personal God" – there's not much point pretending that there's anything religious left. You might as well come clean and admit that you're an atheist with certain values, which are historical, cultural, biological, and personal in origin, and have nothing to do with anything called God." Greg Egan, An Interview With Greg Egan, Eidolon 11, pp. 18–30, January 1993 (accessed April 28, 2008)

- "When I discussed my own atheism and Peter his own belief, he wrote that he needed God as a "friend of loneliness, who does not speak, does not laugh, does not cry"." Greg Egan, Letters from the forgotten, The Age (Australia), February 17, 2005 (accessed April 28, 2008)

- Q: "Are you a religious man?" Eggers: "Most of my siblings and I stopped believing when we were around 14. I'm somewhere between an atheist and an agnostic – I'd be an atheist if I could muster the energy." 'You Ask The Questions: Dave Eggers', The Independent (London), September 30, 2004, Features, p. 5.

- "Saturday, my last night at the [Motel] 6, and I refuse to spend it crushed in my room. But what is a person of limited means and no taste for "carousing" to do? Several times during the week, I have driven past the "Deliverance" church downtown, and the name alone exerts a scary attraction... The marquee in front of the church is advertising a Saturday night "tent revival", which sounds like the perfect entertainment for an atheist out on her own." Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America, Barbara Ehrenreich, Henry Holt and Company, 2001, (p. 66-67) ISBN 0-8050-6389-7

- Interviewed by Terry Gross on NPR's Fresh Air on 8 April 2014 in connection with Ehrenreich's just published book, Living with a Wild God: A Nonbeliever's Search for the Truth about Everything, Ehrenreich confirmed that she had been an avowed atheist since childhood.

- Bart D. Ehrman, Misquoting Jesus, HarperSanFrancisco, 2005, ISBN 0-06-073817-0.

- Reprinted in Hitchens, Christopher, ed. (2007). The Portable Atheist. Philadelphia: Da Capo. ISBN 978-0-306-81608-6.

- "Look, I'm an atheist. People say to me, do you believe in God? No, I don't believe in God." Harlan Ellison in clue book for the computer version of I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream("Harlan Ellison - Celebrity Atheist List". Archived from the original on 2009-01-11. Retrieved 2008-05-27..)

- Esfandiary, F. M. Upwingers: A Futurist Manifesto. p. 185.

- "No God, but value in art of worship". The Sydney Morning Herald. May 4, 2005.

- "He died of prostate cancer in Trinity Hospice, in Clapham, south London, on October 23, 1995. He was a declared atheist and a member of the Humanist Society and he was cremated on October 30 at Putney Vale crematorium, south London." Paul Vaughan: 'Ewart, Gavin Buchanan (1916–1995)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, May 2006 (accessed April 30, 2008).

- "Baptised at 11 ("Did I feel transfigured or just wet?"), Faber lost his faith early. "I left my parents a letter explaining that I didn't believe in God. The more I read, the more I felt that we were dealing with myths: human attempts to come to terms with the big challenges of life. My parents were very upset. My mother said: 'This means we won't meet you in heaven.' For years I was quite a militant atheist. I wanted to burn down all the churches or turn them into second-hand record emporiums." He softened in his thirties. "I don't have any faith myself, but I think that religion is here to stay. When you go to buy a paper you have to accept that the newsagent believes he'll go to a paradise after he dies where there are virgins running around, or he believes the world was created in seven days... there will be some belief that doesn't make any scientific sense. That doesn't mean you can't buy a newspaper from him or ask how his kids are." Faber recently attended an art exhibition at his local church and was moved when the rector told him: 'If you see anybody else out there who looks hungry, just bring them in.' "It is sinful to be too cynical about that", he says. "My feelings are a bit schizophrenic. I get increasingly respectful of people who have faith and increasingly creeped out by them." " Helen Brown interviewing Faber, 'Faith in forgiveness', The Daily Telegraph (London), 15 November 2008, Art, p. 10.

- "I am an atheist, and if an atheist and a pope think the same things, there must be something true. It's that simple! There must be some human truth here that is beyond religion." Prophet of Decline: An interview with Oriana Fallaci, The Wall Street Journal, June 23, 2005 (accessed April 10, 2008).

- American Atheists article on Fisher "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-06-15. Retrieved 2008-05-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "I've been doing media appearances as a secular humanist activist for fifteen years now. I perennially underwent this exchange: REPORTER/HOST: Are you an atheist? ME: I call myself a secular humanist. Secular humanists disbelieve in the supernatural and prefer to use reason, compassion, and the methods of science to build the good life in this life. REPORTER/HOST: But you're an atheist, aren't you? I couldn't sidestep the "A" word. When I tried, it was all I'd get to talk about. Today, I handle this question differently: REPORTER/HOST: Are you an atheist? ME: Yes, but that's only the beginning." Tom Flynn, Why The "A" Word Won't Go Away Archived 2008-06-16 at the Wayback Machine, Council for Secular Humanism op-ed article (accessed April 30, 2008).

- "Follett, who is 58, was born in Cardiff, the son of a tax inspector. His family belonged to the puritanical Plymouth Brethren, so he was barred from watching films and television and even visiting other churches. Sounds like a strict upbringing. Perhaps too strict, given that he is now an atheist. 'Yeah, as soon as I reached the age of reason – about 16 – I stopped going to church. But I also have a sybaritic streak and could never have been happy in any puritanical religion. Self-denial is not my thing." Nigel Farndale, 'Damn Right I Got The Talent', The Sunday Telegraph, October 7, 2007, Section 7 (Books), p. 22.