Fenari Isa Mosque

Fenâri Îsâ Mosque (full name in Turkish: Molla Fenâri Îsâ Câmîi), known in Byzantine times as the Lips Monastery (Greek: Μονὴ τοῦ Λιβός), is a mosque in Istanbul, made of two former Eastern Orthodox churches.

| Fenâri Îsâ Mosque Lips Monastery Fenâri Îsâ Câmîi | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Side view of the Mosque, formerly the Church of St. John the Baptist, Recently restored as of 2022 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Sunni Islam |

| Year consecrated | 1497 |

| Location | |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

Location in the Fatih district of Istanbul | |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°0′55.37″N 28°56′38.40″E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | church with cross-in-square plan (North church) and square plan (south church) |

| Style | Byzantine |

| Groundbreaking | 908 |

| Completed | 1304 |

| Specifications | |

| Minaret(s) | 1 |

| Materials | brick, stone |

Location

The complex is located in the Fatih district of Istanbul, Turkey, along the Adnan Menderes (formerly Vatan) Avenue.

History

Byzantine period

In 908, the Byzantine admiral Constantine Lips[1] inaugurated a nunnery in the presence of the Emperor Leo VI the Wise (r. 886–912).[2] The nunnery was dedicated to the Virgin Theotokos Panachrantos ("Immaculate Mother of God") in a place called "Merdosangaris" (Greek: Μερδοσαγγάρης),[3] in the valley of the Lycus (the river of Constantinople).[2] The nunnery was known also after his name (Monē tou Libos), and became one of the largest of Constantinople.

The church was built on the remains of another shrine from the 6th century,[4] and used the tombstones of an ancient Roman cemetery.[2] Relics of Saint Irene were stored here. The church is generally known as "North Church".

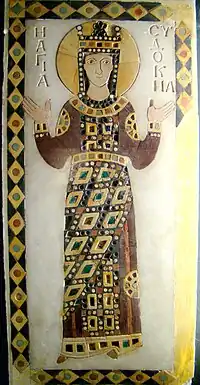

After the Latin invasion and the restoration of the Byzantine Empire, between 1286 and 1304, Empress Theodora, widow of Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos (r. 1259–1282), erected another church dedicated to St. John the Baptist (Ἐκκλησία τοῦ Ἁγίου Ἰωάννου Προδρόμου τοῦ Λιβός)[5] south of the first church. Several exponents of the imperial dynasty of the Palaiologos were buried there besides Theodora: her son Constantine, Empress Irene of Montferrat and her husband Emperor Andronikos II (r. 1282–1328).[4] This church is generally known as the "South Church". The Empress restored also the nunnery, which by that time had been possibly abandoned.[6] According to its typikon, the nunnery at that time hosted a total of 50 women[6][7] and also a Xenon[8] for laywomen with 15 beds attached.[2]

During the 14th century an esonarthex and a parekklesion[9] were added to the church. The custom of burying members of the imperial family in the complex continued in the 15th century with Anna, first wife of Emperor John VIII Palaiologos (r. 1425–1448), in 1417.[10][11] The church was possibly used as a cemetery also after 1453.[10]

Ottoman period

In 1497–1498, shortly after the Fall of Constantinople and during the reign of Sultan Beyazid II (1481–1512), the south church was converted into a mescit (a small mosque) by the Ottoman dignitary Fenarizade Alâeddin Ali ben Yusuf Effendi, Qadi 'asker[12] of Rumeli, and nephew of Molla Şemseddin Fenari,[2] whose family belonged to the religious class of the ulema. He built a minaret in the southeast angle, and a mihrab in the apse.[10] Since one of the head preachers of the madrasah was named Îsâ ("Jesus" in Arabic and Turkish), his name was added to that of the mosque. The edifice burned down in 1633, was restored in 1636 by Grand Vizier Bayram Pasha, who upgraded the building to cami ("mosque") and converted the north church into a tekke (a dervish lodge). In this occasion the columns of the north church were substituted with piers, the two domes were renovated, and the mosaic decoration was removed.[10] After another fire in 1782,[13] the complex was restored again in 1847/48. In this occasion also the columns of the south church were substituted with piers, and the balustrade parapets of the narthex were removed too.[13] The building burned once more in 1918,[14] and was abandoned. During excavations performed in 1929, twenty-two sarcophagi have been found.[14] The complex has been thoroughly restored between the 1950s and 1960s by the Byzantine Institute of America,[15] and since then serves again as a mosque.[13]

Architecture and decoration

North church

The north church has an unusual quincuncial (cross-in-square) plan, and was one of the first shrines in Constantinople to adopt this plan, whose prototype is possibly the Nea Ekklesia ("New Church"), erected in Constantinople in the year 880, of which no remains are extant.[16] During the Ottoman period the four columns have been replaced with two pointed arches which span the whole church.[17]

The dimensions of the north church are small: the naos is 13 metres (43 feet) long and 9.5 metres (31.2 feet) wide, and was sized according to the population living in the monastery at that time. The masonry of the northern church was erected by alternating courses of bricks and small rough stone blocks. In this technique, which is typical of the Byzantine architecture of the 10th century,[18] the bricks sink in a thick bed of mortar. The building is topped by an Ottoman dome pierced by eight windows.[17]

This edifice has three high apses: the central one is polygonal, and is flanked by the other two, which served as pastophoria: prothesis and diakonikon.

The apses are interrupted by triple (by the central one)and single lancet windows.[17] The walls of the central arms of the naos cross have two orders of windows: the lower order has triple lancet windows, the higher semicircular windows. Two long parekklesia, each one ended by a low apse, flanks the presbytery of the naos. The angular and central bays are very slender. At the four edges of the building are four small roof chapels, each surmounted by a cupola.

The remainders of the original decoration of this church are the bases of three of the four columns of the central bay, and many original decorating elements, which survive on the pillars of the windows and on the frame of the dome. The decoration consisted originally in marble panels and coloured tiles: the vaults were decorated with mosaic. Only spurs of it are now visible.[18]

As a whole, the north church presents strong analogies with the Bodrum Mosque (the church of Myrelaion).[19]

South church

The south church is a square room surmounted by a dome, and surrounded by two deambulatoria,[20] an esonarthex and a parekklesion (added later). The north deambulatorium is the south parekklesion of the north church. This multiplication of spaces around the central part of the church, typical of late Palaiologian architecture, was motivated by the need for more space for tombs, monuments erected to benefactors of the church, etc.[21] The central room is divided from the aisles by a triple arcade. During the mass the believers were confined in the deambulatoria, which were shallow and dark, and could barely see what happened in the central part of the church.

The masonry is composed of alternated courses of bricks and stone, typical of late Byzantine architecture in Constantinople.

The lush decoration of the south and of the main apses (the latter is heptagonal), is made of a triple order of niches, the middle order being alternated with triple windows. The bricks are arranged to form patterns like arches, hooks, Greek frets, sun crosses, swastikas and fans.[22] Between these patterns are white and dark red bands, alternating one course of stone with two to five of bricks. This is the first appearance of this most important decorating aspect of Palaiologian architecture in Constantinople.

The church has an exonarthex surmounted by a gallery, which was extended to reach also the north church. The parekklesion was erected alongside the southern side of the south church, and was connected with the esonarthex, so that the room surrounds the whole complex on the west and south side. Several marble sarcophagi are placed within it.

As a whole, this complex represents a notable example of middle and late Byzantine Architecture in Istanbul.

See also

References

- The name of the founder has been found in an inscription on the cornice of the apse. Krautheimer (1986), p. 409.

- Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 126

- This toponym has a Persian etymology ("Merd-il-sachra"), and is composed of the two Persian words Merdo (meaning "man"), and sachra (meaning "solitude"): "Man of solitude". Janin (1964), p. 361.

- Gülersoy (1976), p. 258.

- "This church was added to the thirty five ones dedicated to this Saint, which existed in Constantinople in the tenth century!" Krautheimer (1986), p. 436

- Talbot (2001), p. 337

- Krautheimer (1986), p. 409.

- This was a charitable institution, something between an hospital and a nursing home. Talbot (2001), p. 337

- The parekklesion is a chapel leaning to the side of the church or of the narthex.

- Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 127.

- Freely says that Anna was buried in the dead of night to avoid creating a public panic due to rumors of the Bubonic plague.

- The Qadi 'asker ("Army-Judge") was the supreme military magistrate, and was one of the most important figures in the State organisation of the Ottoman Empire.

- Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 128

- Eyice (1955), p. 80.

- "Finding Aid to The Byzantine Institute and Dumbarton Oaks Fieldwork Records and Papers, ca. late 1920s-2000s, MS.BZ.004, Image Collections and Fieldwork Archives, Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C." HOLLIS for Archival Discovery. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- Krautheimer (1986), p. 388.

- Van Millingen (1912), p. 128

- Krautheimer (1986), p. 405.

- Krautheimer (1986), p. 404.

- A deambulatorium is an aisle which encircles the central part of a church.

- Krautheimer (1986), p. 457.

- Krautheimer (1986), p. 467.

Sources

- Van Millingen, Alexander (1912). Byzantine Churches of Constantinople. London: MacMillan & Co.

- Janin, Raymond (1964). Constantinople Byzantine (in French) (2 ed.). Paris: Institut Français d'Etudes Byzantines.

- Eyice, Semavi (1955). Istanbul. Petite Guide a travers les Monuments Byzantins et Turcs (in French). Istanbul: Istanbul Matbaası.

- Gülersoy, Çelik (1976). A guide to Istanbul. Istanbul: Istanbul Kitaplığı. OCLC 3849706.

- Mathews, Thomas F. (1976). The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul: A Photographic Survey. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01210-2.

- Müller-Wiener, Wolfgang (1977). Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul bis zum Beginn d. 17 Jh (in German). Tübingen: Wasmuth. ISBN 978-3-8030-1022-3.

- Krautheimer, Richard (1986). Architettura paleocristiana e bizantina (in Italian). Turin: Einaudi. ISBN 88-06-59261-0. (Note. While the page numbers in the citations refer to the Italian edition, an English edition - not as up-to-date as the Italian one - is also available: Krautheimer, Richard (1984). Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture (Fourth ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05294-7.)

- Freely, John (2000). Blue Guide Istanbul. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-32014-6.

- Talbot, Alice-Mary (2001). "Building Activity under Andronikos II". In Necipoğlu, Nevra (ed.). Byzantine Constantinople: Monuments, Topography and everyday Life. Leiden, Boston, Köln: Brill. ISBN 90-04-11625-7.

External links

- Byzantium 1200 - Lips Monastery

- "Typikon of Theodora Palaiologina for the Convent of Lips in Constantinople" (trans. Alice-Mary Talbot), from Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents: A Complete Translation of the Surviving Founder's Typika and Testaments, Thomas, J. & Hero, A.C. (eds.) (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington D.C. 2000)