Legion of Merit of Chile

The Legion of Merit of Chile (Spanish: Legion de Mérito de Chile), frequently abbreviated to the Legion of Merit or the Legion, was a Chilean multi-class order of merit established on 1 June 1817 by Bernardo O'Higgins to recognise distinguished personal merit contributing to the independence of Chile or to the nation. Membership of the Legion conferred a variety of privileges in Chile and its members were entitled to wear insignia according to the class conferred. The Legion of Merit of Chile was abolished in 1825.

| Legion of Merit (Legion de Mérito de Chile) | |

|---|---|

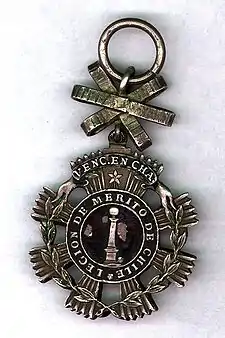

Obverse of the Type I breast badge of the Legion of Merit of Chile, IV Class. Shown is the design used for those who fought at the Battle of Chacabuco, June 1817. This specimen is missing its enamel work. | |

| Awarded by Republic of Chile | |

| Type | Order of merit |

| Motto | Libertad |

| Eligibility | Chilean citizens and foreign supporters of Chile |

| Awarded for | Distinguished personal merit contributing to the independence of Chile or to the nation |

| Status | Abolished in 1825 |

| President of the institution | Supreme Director of Chile |

| Grades | I: Grand Officers II: Officers III: Sub-officers IV: Legionnaires |

Composition

The Legion of Merit of Chile was established as an order of merit along similar lines to the French Légion d'honneur.[1] The Supreme Director of Chile (as the Chilean head of state was then known) was established as the head of the Legion.[2] The order was established in four classes:

- Grand Officers of the Legion (Spanish: Grandes Oficiales de la Legion), I Class - for Brigadiers General and those deemed equivalent.[3]

- Officers of the Legion (Spanish: Oficiales de la Legion), II Class - for Colonels and those deemed equivalent.[3]

- Sub-officers of the Legion (Spanish: Sub-oficiales de la Legion), III Class - for Sergeant Majors and those deemed equivalent (historically equivalent to the current rank of Major).[3]

- Legionnaires or Members of the Legion (Spanish: Legionarios ó Miembros de la Legion), IV Class - for Lieutenants and those deemed equivalent.[3]

All appointees to the Legion were required to swear on their honour to defend Chile, to sustain its liberty and independence and not to forget the duty and 'glorious distinction' for which they were decorated.[4]

Council of the Legion

The Council of the Legion (Spanish: El Consejo de la Legion) was composed of the Supreme Director as President (ex officio), the Grand Officers of the Legion (the most senior was appointed Vice President of the Legion), twelve Officers of the Legion, six Sub-officers of the Legion and six Legionnaires.[4] The council was charged with reforming the laws and regulations of the Legion as required; presiding over meetings and assemblies of the Legion; approving appointments to the Legion (this task was performed by a five-person panel and excluded the initial appointments to the Legion); considering cases of alleged dishonourable conduct by appointees to the Legion (if found guilty, their appointment could be revoked and they were then prohibited from being reappointed); and overseeing the administration and finances of the Legion (including administering the pensions for appointees).[5]

History

Portrait by José Gil de Castro

Establishment

The Legion of Merit was established by the Supreme Director of the newly independent Chile, Liberator General Bernardo O'Higgins, on 1 June 1817, in the wake of the Battles of Chacabuco and Maipú,[6] to recognise distinguished contributions to the liberation of Chile or to the nation.[2] At the time, it was the most senior honour of Chile.[2] O'Higgins was the Chilean-born illegitimate son of Ambrosio O'Higgins, 1st Marquis of Osorno,[7] a Spanish officer born in Ireland, who became governor of Chile and later viceroy of Peru. His mother was Isabel Riquelme,[7] daughter of Don Simón Riquelme y Goycolea, a member of the Chillán Council.[8] Notwithstanding his aristocratic background, O'Higgins abolished the system of nobility in Chile;[9] establishment of the Legion of Merit helped to fill the void with a more egalitarian recognition system.[1] This was in keeping with the ideals of many of the revolutionaries, but alienated the existing aristocracy.[1][9]

The decree establishing the Legion provided that the initial appointments were for participants at the Battle of Chacabuco with the initial appointments as Grand Officers of the Legion comprising: the Supreme Director of Chile (Bernardo O'Higgins), the Supreme Director of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (José de San Martín) and the senior Generals at the Battle of Chacabuco.[10] The initial appointments as Officers of the Legion were to comprise the commanders of the armies at the battle and a Captain from each unit elected by the members of the unit, whilst a subaltern of the General Staff elected by the officers at Chacabuco was to be appointed a Sub-officer of the Legion.[10] Finally, based on a vote of the officers of each unit, three Captains and three subalterns of the Regiment of Mounted Grenadiers, two Captains and two subalterns of each infantry unit and one Captain and one subaltern of Artillery were to be appointed Legionnaires.[11] In addition, twenty five sergeants, corporals or soldiers (from across all units) were to be selected by the Council of the Legion for appointment as Legionnaires based on distinguished performance during the battle.[11]

The establishing decree further provided that subsequent appointments could only be made by the Council of the Legion where individuals had demonstrated 'distinguished personal merit'; these appointments were not restricted to the military but could include ministers of religion, judges, government administrators, intelligentsia, artists or any other person found to have suitably distinguished themselves.[12]

Privileges of members

The regulations of the Legion provided members with several privileges. Members were awarded an annual pension funded from the proceeds of estates seized from Spanish Royalists who had fled Chile during the Chilean War of Independence.[13] Annual pensions for Grand Officers were 1000 pesos, for Officers they were 500 pesos, for Sub-officers 250 pesos and for Legionnaires they were 150 pesos.[13] Members of the Legion accused of military or civil crimes had the right to claim trial before a private court of the Legion, drawn from the Legion's military membership; where this was not possible and prior to the execution of any sentence, they were entitled to have the verdict and sentence of the ordinary civilian or military court reviewed by the Legion's court who could either confirm or revoke the verdict and sentence.[14] In an era where the Chilean military often had a poor reputation for discipline,[15] military members of the Legion were entitled to freely enter and exit their barracks at any time and others were prohibited from insulting or in any way harassing members of the Legion.[16] Members of the Legion, when traveling, were entitled to stay overnight at any ranch and to be given food and lodgings for themselves and any companions that they might have been traveling with.[17]

Special provisions were made for citizens of the United States of Rio de la Plata to deconflict those aspects of the Legion that were incompatible with foreign citizenship. These included modified pension arrangements, a modified oath (which avoided swearing allegiance to Chile), and limitations on the right to be tried by a court of the Legion (which was only recognised for offences committed within Chile, although charges of dishonourable behaviour could still be heard to determine the individual's fitness to remain a member of the Legion).[18]

Demise

The Chilean Senate, under pressure from Ramón Freire, attempted to abolish the order in early 1823, citing a lack of financial funds to support the pensions allocated to its members.[19] O'Higgins refused to endorse this decision and challenged the Senate's capacity to do so.[19] However, after O'Higgins resigned in January 1823, the Senate removed the Legion's access to the proceeds of the seized estates, with the exception of 3000 pesos annually to establish a naval school.[19] The existing aristocracy in Santiago were concerned that the Legion was becoming a new form of nobility (which had been abolished in Chile) and saw it as a threat to their status.[19] Finally, in June 1825, the President of the Regency Council, José Miguel Infante, removed the remaining financial allocation[19] and rescinded the act establishing the Legion.[20] Whilst no more appointments were made to the Legion, later imagery suggests that existing members of the Legion maintained their entitlement to wear the insignia previously conferred.

Insignia

As with other contemporary orders, the Legion of Merit used a variety of insignia to distinguish those appointed to the various classes of the order.

Badge of the Legion

Obverse. The obverse of the badge consists of a five-point star (point upwards) surmounted with a small loop ring, to fasten the ribbon, each point ending in a ball finial. Upon the center of the star is attached a disc comprising a circlet surrounding a central disc. The circlet is inscribed with the text LEGION DE MERITO DE CHILE. The central disc consists of a sky blue enamel background upon which is depicted a column crowned with a globe, the whole resting on a ground compartment (the central design is taken from the then Chilean coat of arms). The star rests upon a laurel wreath with enamel highlights, linked at the top by a small scroll inscribed with the text VENC EN CHA, i.e. Vencedor en Chacabuco (English: Victor of Chacabuco) for those who had fought at the Battle of Chacabuco or LIBERTAD (English: Liberty) for those who had not. Underneath the star and laurel wreath extend fimbriated rays in silver (Legionnaires) or gold (higher classes).[21]

Reverse. The design of the badge's reverse is similar to the obverse with the distinctions that the circlet is inscribed with the text HONOR Y PREMIO AL PATRIOTISMO (English: Honour and Award for Patriotism), the scroll is inscribed with the text O'HIG S INST and the central disc depicts an erupting volcano in the middle of a mountain range.[21]

The Type I Class III and Class IV badge omits the five-point star. The Type II Class IV badge and the higher class badges used a mix of enamel, silver, gold and (for Class I badges) jewels. Some badges were produced with the circlet and/or scroll text swapped between the obverse and reverse sides.[22]

Method of wear

Those appointed to the Legion were encouraged to wear the insignia of the Legion with all forms of dress. If they did not wish to wear the badge, the regulations provided that they could wear the sky blue ribbon of the Legion[23] passed through the buttonhole of their coat to an attachment device or small pin in either silver (for Legionnaires) or gold (for the remaining classes).[10]

Grand Officers. In dress uniform, Grand Officers of the Legion wore a gold star on the left side with a representation of the arms of the Legion. They also wore a sky blue sash over the right shoulder gathered in a bow over the left hip from which was hung the badge of the Legion. When not in dress uniform, Grand Officers of the Legion could wear the badge suspended from the buttonhole of their coat with a rosette of sky blue ribbon.[21]

Officers. In dress uniform, Officers of the Legion wore the gold badge of the Legion suspended from the neck by a broad sky blue ribbon. When not in dress uniform, Officers of the Legion could wear the badge suspended from the buttonhole of their coat with a rosette of sky blue ribbon.[21]

Sub-officers. Sub-officers of the Legion wore the gold badge of the Legion suspended from the buttonhole of their coat with a sky blue ribbon.[21]

Legionnaires. Legionnaires wore the silver badge of the Legion suspended from the buttonhole of the coat with a sky blue ribbon.[21]

Notable members

Grand Officers

- Bernardo O'Higgins, appointed a Grand Officer of the Legion in 1817.[24]

- Ramón Freire, originally appointed an Officer of the Legion[25] and later advanced to Grand Officer.[26]

- José de San Martín, appointed a Grand Officer of the Legion in 1817.[27]

Officers

- Rudecindo Alvarado.[1]

- Antonio Beruti.[19]

- Tomás Guido, appointed a Sub-officer of the Legion in 1820[28] and advanced in 1822 to Officer.[1][29]

- Juan Gregorio de las Heras.[1]

- Mariano Necochea.[1]

- José Matía Zapiola.[19]

- José Ignacio Zenteno.[30]

Sub-officers

Legionnaires

- José Antonio Rodríguez Aldea, appointed a Legionnaire in 1821.[31]

- Giuseppe Rondizzoni.[32]

References

- Abarca, Jorge (2006). "Los militares ante la élite: Imagen y modalidades de captación en Perú y Chile (1817-1824)" (PDF). Hispania Nova: Revista electrónica de Historia Contemporánea (in Spanish). Red Iris. 2006 (6): 12. ISSN 1138-7319. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- O'Higgins, Bernardo (1819). Recopilacion de los decretos expedidos por el Exmo. Sr. director supremo sobre la institucion y reglamento de la Legion de merito de Chile [Collection of the decrees issued by the Hon. Sr. Supreme Director, on the institution and procedure of the Legion of Merit of Chile, established on 1 June of 1817 years] (in Spanish) (Impr. de Gobierno, Santiago, Chile ed.). Harvard University Library. p. 1. Retrieved 9 July 2012 – via Page Delivery Service, Collection Development Department, Widener Library, HCL.

- O'Higgins, Bernardo (1819), pp. 1–2, 10–11

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - O'Higgins, Bernardo (1819), p. 6

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - O'Higgins, Bernardo (1819), pp. 6, 9–10

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Abarca, Jorge (2006), p. 4

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Kinsbruner, Jay (2012). "Bernardo O'Higgins". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- Hamre, Bonnie (2012). "Bernardo O'Higgins: Libertador de Chile - a red-haired Irish/Chilean". South America Travel. About.com [New York Times Company]. p. 1. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- Luca, Francis (2003). "O'Higgins, Bernardo (1778-1842)". In Paige, Melvin; Sonnenburg, Penny M (eds.). Colonialism: An international social, cultural, and political encyclopedia, Vol 2. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 438. ISBN 1-57607-762-4. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- O'Higgins, Bernardo (1819), p. 4

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - O'Higgins, Bernardo (1819), p. 5

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - O'Higgins, Bernardo (1819), pp. 8, 14

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - O'Higgins, Bernardo (1819), pp. 12–13

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - O'Higgins, Bernardo (1819), pp. 11–12

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Abarca, Jorge (2006), pp. 11–12

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - O'Higgins, Bernardo (1819), p. 12

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - O'Higgins, Bernardo (1819), p. 11

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - O'Higgins, Bernardo (1819), pp. 14–24

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Abarca, Jorge (2006), p. 13

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Abarca, Jorge (2006), p. 15

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - O'Higgins, Bernardo (1819), pp. 2–3

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Yashnev, Yuri. "Чили: ОРДЕН ЛЕГИОНА ЗАСЛУГ (Chile: Order of Legion of Merit)". Каталог наград мира Catalogue of World Awards) (in Russian and English). Sobiratel. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- Barrio, Antonio Prieto (2012). "Coleccion de Cintas - Chile". Colecciones Militares (in Spanish). Antonio Prieto Barrio. p. 4. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- El Consejo de la Legion de Merito de Chile (2 November 1818). "Diploma de La Legion de la Merito de Chile - Bernardo O'Higgins". Каталог наград мира (Catalogue of World Awards) (in Spanish). Sobiratel [original publisher El Consejo de la Legion de Merito de Chile]. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- Gil de Castro, José (1820). "Retrato del Coronel General don Ramón Freire Serrano" (in Spanish). Santiago, Chile: Museo Histórico Nacional. Painting. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- Unknown. "Ramón Freire Serrano (1787-1851)". Archivo Fotográfico de la Universidad de Chile. Santiago, Chile: Universidad de Chile. Photograph. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Figuerola, Justo (d. 1854) (1822). Elogio Del Excelentisimo Señor Don Jose De San Martin Y Matorras, : Protector Del Peru, Generalisimo De Las Fuerzas De Mar Y Tierra, Institutor De La Órden Del Sol, Gran Oficial De La Legion De Merito De Chile, Y Capitan General De Sus Exercitos (in Spanish). Lima, Peru: Universidad Nacional Mayor De San Marcos. Title page. ISBN 9785872386179. OCLC 43303704.

- Herrera, José Hipólito, ed. (1862). El album de Ayacucho, coleccion de los principales documentos de la guerra de la independencia del Perú y de los cantos de victoria y poesias reletivas a ella (in Spanish) (2 November 2007 Digitised ed.). Lima, Peru: Aurelia Alfaro. p. 28. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

Tomás Guido sub-oficial.

- Guido, Tomás; Carlos Guido y Spano (1882). Vindicación histórica (in Spanish) (8 August 2008 Digitised ed.). C. Casavalle. p. 360. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

Dos años antes le habia condecorado con la Legion de Mérito de Chile, en classe Sub-Oficial, ascendiéndole á Oficial de la misma órden en 1822, siendo Ministro de Guerra del Perú

- Desmadril, Narciso (1854). "José Ignacio Zenteno (Santiago, 28 de julio de 1786 - Santiago, 16 de julio de 1847) fue Ministro de Guerra y Marina de Bernardo O'Higgins". Galería nacional, o Colección de biografías y retratos de hombres célebres de Chile (in Spanish). Santiago, Chile: Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. Photograph. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

-

"Capítulo XXXVIII: Diplomas, Títulos, etc". Escritos y documentos del Ministro de O'Higgins, Doctor José Antonio Rodríguez Aldea y otros concernientes a su persona. 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

1. Diploma de legionario de la Legión de Mérito de Chile. 10 de febrero de 1821. (341)

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Barbarini, Caterina (5 August 2009). "Dal Cile a Mezzani: una nipote sulle tracce del generale-eroe" (in Italian). Gazetta di Parma. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

Proprio in Cile si stabilì una volta ottenuta l'indipendenza. Membro della Legione del Meritum de Chile, il generale Rondizzoni rivive ancora oggi nel ricordo della sua patria adottiva, che gli ha dedicato vie, piazze e monumenti e persino un'opera fortificata del porto di Talcahuano

Bibliography

- Abarca, Jorge (2006). "Los militares ante la élite: Imagen y modalidades de captación en Perú y Chile (1817-1824)" (PDF). Hispania Nova: Revista electrónica de Historia Contemporánea (in Spanish). Red Iris. 2006 (6). ISSN 1138-7319.

- Eyzaguirre, Jaime (1934). Historia de la Legión de Mérito (in Spanish). Santiago, Chile: Academia Chilena de la Historia.

- O'Higgins, Bernardo (1819). Recopilacion de los decretos expedidos por el Exmo. Sr. director supremo sobre la institucion y reglamento de la Legion de merito de Chile [Collection of the decrees issued by the Hon. Sr. Supreme Director, on the institution and procedure of the Legion of Merit of Chile, established on 1 June of 1817 years] (in Spanish) (Impr. de Gobierno, Santiago, Chile ed.). Harvard University Library – via Page Delivery Service, Collection Development Department, Widener Library, HCL.

- Yashnev, Yuri. "Чили: ОРДЕН ЛЕГИОНА ЗАСЛУГ (Chile: Order of Legion of Merit)". Каталог наград мира Catalogue of World Awards) (in Russian and English). Sobiratel. Good selection of images