Lango people

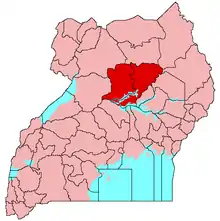

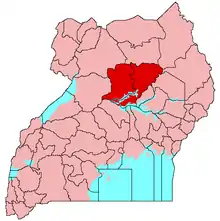

The Lango are a Nilo-Hamitic ethnic group of the Ateker peoples.[3] They live in north-central Uganda, in a region that covers the area formerly known as the Lango District until 1974, when it was split into the districts of Apac and Lira, and subsequently into several additional districts. The current Lango Region now includes the districts of Amolatar, Alebtong, Apac, Dokolo, Kole, Lira, Oyam, Otuke, and Kwania.[4] The total population of the Lango District is around 1,500,000.[5]

| |

Lango sub-region | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,500,000[1][2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Lango dialect, English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ateker peoples, other Hamites |

The Lango speak in “LebLango”, a mixture of Ateker peoples dialects and broken Luo languages (Lwo).[6].

Early history

.jpg.webp)

The Lango oral tradition states that they were part of the "Lango race" during the migration period. This group later split into several distinct groups before entering Uganda[7] (see Tarantino, Odwe, Crazollara, Uzoigwe). The name “Lango” is found in Teso, Kumam, Karamojong, Jie, and Labwor vocabularies, reflecting that how these groups once used to belong to the Lango race.[7]

Hutchinson (1902) states

"One of the chief nations of the late kingdom of Unyoro are the Lango (Lango, Longo) people, who although often grouped with the Nilotic Negroes, are really of the Galla stock and speech. They form, in fact, an important link in the chain of Hamitic peoples who extend from Galla-land through Unyoro and Uganda southwards to Lake Tanganyika. Their territory which occupies both banks of the Somerset or Victoria Nile between Foweira and Magungo, extends eastwards beyond Unyoro proper to the valley of the Chol, one of the chief upper branches of the Sobat.[8][9][10] They still preserved their mother tongue amid Bantu and Negroid populations, and are distinguished by their independent spirit, living in small groups, and recognizing no tribal chief, except those chosen to defend the common interest in the time of war"[7] (p. 360).

Hutchinson (1902) adds

"The Lango is especially noted for the care bestowed on their elaborate and highly fantastic head-dress. The prevailing fashion may be described as a kind of a helmet... Lango women, who amongst the finest and most symmetrical of the Equatorial lake regions, wear little clothing or embellishments beyond west-bands, necklaces, armlets, and anklets" (p. 360).

Icaya (Isaya) Ogwangguji, M.B.E.

Rwot Ogwangguji was born in 1875 in Abedpiny village in Lira District (Okino, Patrick, and Odongo, Bonney). He was the son of a Rwot (chief) – Rwot Olet Apar, the leader of the Oki clan.[11] His first administrative chief title was the Jago (sub-chief) of Lira. In 1918, he was elected county chief (Rwot) by Erute county, Lango. He continued as Rwot of Erute county until February 28, 1951, and was later promoted to the title of Rwot Adwong (Senior Chief). Rwot Ogwangguji is known as a chief who bridged "old Lango" into "new Lango" through his extensive work history during a period of many changes in the 20th century in Uganda. He was awarded the M.B.E. in the New Year's Honors in 1956 and subsequently retired in December 1957.[11] (Wright, M.J., Uganda Journal, Vol. 22, Issue 2, 1958).

Military

Driberg described Lango people as

"brave and venturesome warriors who have won fear and respect of their neighbours...not being idle witnesses to watching of the misfortunes of their neighbours...treating facts of life with no sense of false modesty...".[10]

The Lango army was united under one military leader chosen from available men, and all had to agree to be led by him.[9][7] These military leaders would lead the Lango army against other groups. Their authority ended when the war was over, and they all returned to their clans and resumed their daily occupations and were not entitled to any special benefits. Famous military leaders were Ongora Okubal, who brought the Lango to their present land, Opyen who succeeded Ongora Okubal and was followed by Arim Oroba, and Agoro Abwango. Agoro Abwango led his men to fight the Banyoro and was killed in Bunyoro.[12] The Lango oral literature has it that as the soldiers who went to help Kabalega retreated towards the Nile, they helped Kabalega and Mwanga, the deposed King of Bunyoro and Buganda respectively cross the Nile River.[9] They were moved along the northern corridor of Lake Kwania. At the time, a warrior called Obol Ario who had conquered much of the northern part of the lake was there. It's believed he helped smuggle the two deposed kings towards Dokolo, where they settled at Kangai. Obol Ario of Apac Okwero Ngec Ayita Clan eventually settled at Amac where he later died and was buried.[8]

Land tenure

Land in the pre-colonial era was common land, and any untilled area belonged to the first person or family who tilled it, and it was passed on to the eldest son.[13] "Land which had not been cultivated in the past could be tilled by any family, and, when once it had been tilled, the community regarded it as the property of the family whose ancestor first cultivated it."[12] Traditional land tenure is still widely used in rural areas.[11][8]

Culture

Although many Lango practice Islam or Christianity, the influence of traditional beliefs still plays a significant role in the religious lives of the Lango. In traditional Lango myth, each individual has a guardian spirit and metaphysical soul. Additionally, ancestral cults and belief in the supreme god, Jok, played a large role in the religion.[14]

Primary occupations of the Lango people include farming and raising livestock.[14]

References

Footnotes

- "Uganda - World Directory of Minorities & Indigenous Peoples". Minority Rights Group. 19 June 2015.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics. "National Population and Housing Census 2014 - Main Report" (PDF).

- "The Nilo-Hamites". Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- "Invest in Lango" (PDF). Uganda Investment Authority.

- "2014 Uganda Population and Housing Census – Main Report" (PDF). Uganda Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- "2020 Lango people" (PDF). Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- Uzoigwe, G. N. The beginnings of Lango society : a review of evidence. OCLC 38562622.

- Tarantino, A (1949). Lango clans. Makerere University Library: The Uganda Journal.

- Odada, M. A. E (1971). The Kumam: Langi or lteso. National Library of Uganda: The Uganda Journal.

- "The Lango: A Nilotic Tribe of Uganda". World Digital Library. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- Erimayo, Olyech (1936). The anointing of clan heads among the Lango. Makerere University Library: The Uganda Journal.

- Kihangire, p. 22

- Curley, Richard T.; Curley, Richard Turner (1 January 1973). Elders, Shades, and Women: Ceremonial Change in Lango, Uganda. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02149-5.

- Yakan, Mohamad (2017). Almanac of African Peoples and Nations. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-28930-6.

Sources

- Julius peter Odwee 2013 " Tricentenary of the Lango people in Uganda"

- Kihangire, Cyprianus (1957). "The marriage customs of the Lango tribe (Uganda) in relation to canon Law"

- Curley, Richard T (1973). Elders, Shades, and Women: Ceremonial Change in Lango, Uganda.

- Tosh, John (1979). Clan Leaders and Colonial Chiefs in Lango: The Political History of an East African Stateless Society 1800–1939.

- Hutchinson, H.N., Walter, J., & Lydekker, R. (1902). The living races of mankind: a popular illustrated account of the customs, habits, pursuits, feasts and ceremonies of the races of mankind throughout the world.

- Julius P.O. Odwe. Proposal to Celebrate a Tricentenary (300 years) of Lango Existence, Importance and Contributions to Uganda. A conference proposal presented to the Prime Minister, Lango Cultural Foundation, Lira (Uganda), 11 November 2011.

- Wright, M.J. (September 1958),"The early life of Rwot Isaya Ogwangguji, M.B.E." Volume 22, Issue 2. Pgs. 131–138.

- "Lango's first palace." New Vision online 18 November 2013.

- Tarantino, Angelo. Lango i kare acon (Lango before colonialism). Fountain Publishers, 2004.