Lake Oswego, Oregon

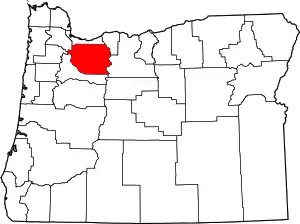

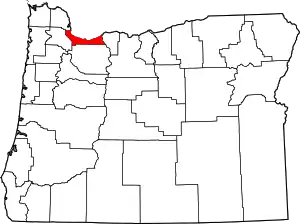

Lake Oswego (/ɒsˈwiːɡoʊ/ oss-WEE-goh) is a city in the U.S. state of Oregon, primarily in Clackamas County, with small portions extending into neighboring Multnomah and Washington counties.[6] Population in 2020 was 40,731, a 11.2% increase since 2010, making it the 11th most populous city in Oregon. Located about 7 miles (11 km) south of Portland and surrounding the 405-acre (164 ha) Oswego Lake, the town was founded in 1847 and incorporated as Oswego in 1910. The city was the hub of Oregon's brief iron industry in the late 19th century, and is today a suburb of Portland.

Lake Oswego | |

|---|---|

| Lake Oswego, Oregon | |

Oswego Lake in the center of the city | |

.jpg.webp) Flag  Seal | |

Location in Oregon | |

Lake Oswego Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates (City Hall): 45.41956°N 122.66755°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Oregon |

| Counties | Clackamas, Multnomah, Washington |

| Founded | 1847, incorporated 1910 |

| Named for | Oswego, New York[1] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor[2] | Joe Buck |

| • City Council[2] | Ali Afghan Trudy Corrigan Massene Mboup Aaron Rapf Rachel Verdick John Wendland |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11.48 sq mi (29.75 km2) |

| • Land | 10.83 sq mi (28.05 km2) |

| • Water | 0.66 sq mi (1.70 km2) |

| Elevation | 249 ft (76 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 40,731 |

| • Density | 3,760.94/sq mi (1,452.08/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (Pacific) |

| ZIP codes | 97034–97035 |

| Area code(s) | 503 and 971 |

| FIPS code | 41-40550[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2411606[6] |

| Website | www.ci.oswego.or.us |

| Elevation from the Geographic Names Information System | |

History

Early history

The Clackamas people once occupied the land that later became Lake Oswego,[7] but diseases transmitted by European explorers and traders killed most of the natives. Before the influx of non-native people via the Oregon Trail, the area between the Willamette River and Tualatin River had a scattering of early pioneer homesteads and farms.

19th century

As settlers arrived, encouraged by the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 and the subsequent Homestead Act, they found the land underoccupied.

Albert Alonzo Durham founded the town of Oswego in 1847, naming it after Oswego, New York.[8] He built a sawmill on Sucker Creek (now Oswego Creek), the town's first industry.[7]

In 1855, the federal government forcibly relocated the remaining Clackamas people to the Grand Ronde Indian Reservation in nearby Yamhill County.[7]

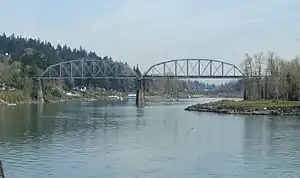

During this early period in Oregon history, most trade proceeded from Portland to Oregon City via the Willamette River, and up the Tualatin River valley through Tualatin, Scholls, and Hillsboro. The thick woods and rain-muddied roads were major obstacles to traveling by land. The vestiges of river landings, ferry stops, and covered bridges of this period can still be seen along this area. A landing in the city's present-day George Rogers Park is thought to have been developed by Durham around 1850 for lumber transport; another landing was near the Tryon Creek outlet into the Willamette.

In 1865, prompted by the earlier discovery of iron ore in the Tualatin Valley, the Oregon Iron Company was incorporated. Within two years, the first blast furnace on the West Coast was built, patterned after the arched furnaces common in northwestern Connecticut, and the company set out to make Oswego into the "Pittsburgh of the West".[9] In 1878, the company was sold off to out-of-state owners and renamed the Oswego Iron Company, and in 1882, Portland financiers Simeon Gannett Reed and Henry Villard purchased the business and renamed it the Oregon Iron and Steel Company.[10]

_(clacDA0239).jpg.webp)

The railroad arrived in Oswego in 1886, in the form of the Portland and Willamette Valley Railway. A 7-mile-long (11 km) line provided Oswego with a direct link to Portland. Prior to this, access to the town was limited to primitive roads and riverboats. The railroad's arrival was a mixed blessing; locally, it promoted residential development along its path, which enabled Oswego to grow beyond its industrial roots, but nationally, the continued expansion of the freight railroad system gave easy local access to cheaper and higher quality iron from the Great Lakes region. This ultimately led to the local industry's demise.[7][10]

By 1890, the industry produced 12,305 tons of pig iron,[7] and at its peak provided employment to around 300 men. The success of this industry greatly stimulated the development of Oswego, which by this time had four general stores, a bank, two barber shops, two hotels, three churches, nine saloons, a drugstore, and even an opera house.[9]

The iron industry was a vital part of a strategy designed by a few Portland financiers who strove to control all related entrepreneurial ventures in the late 19th century. Control of shipping and railroads was held under the Oregon Steam Navigation Company, later to become the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company. This local monopoly responded to the area's increasing demand for iron and steel, and grew to play a key role in economic history throughout the area.

20th and 21st centuries

The Oregon Iron and Steel Company adapted to the new century by undertaking programs in land development, selling large tracts of the 24,000 acres (97 km2) of land it owned, and power, building a plant on Oswego Creek starting in 1905, and erecting power poles in subsequent years to supply power to Oswego citizens. With the water needs of the smelters tailing off, the recreational potential of the lake and town was freed to develop rapidly.[7]

In 1910, the town of Oswego was incorporated.[7] The Southern Pacific Railroad, which had acquired the P&WVR line at the end of the 19th century, widened it from narrow to standard gauge and in 1914 electrified it, providing rapid, clean, and quiet service between Oswego and Portland. The service was known as the Red Electric.[7]

Passenger traffic hit its peak in 1920 with 64 trains to and from Portland daily. Within nine years of the peak, passenger service ended, and the line was used for intermittent freight service to Portland's south waterfront until its abandonment in 1984. The line was preserved, however, and the Willamette Shore Trolley provides tourist rides on the line today.

One of the land developers benefiting from sales by OI&S was Paul Murphy, whose Oswego Lake Country Club helped promote the new city as a place to "live where you play."[7] Murphy was instrumental in developing the first water system to supply the western reaches of the city, and also played a key role in encouraging the design of fine homes in the 1930s and 1940s that ultimately established Oswego as an attractive place to live. In the 1940s and 1950s, continued development helped spread Oswego's residential areas.[7]

Mass transit service after the end of electric interurban service was provided by Oregon Motor Stages, but that company suspended all operations following a drivers' strike in 1954.[11] In 1955, a newly formed private company, Intercity Buses, Inc., began operating bus service connecting Oswego with downtown Portland and Oregon City.[12] This service was taken over by TriMet in 1970.

In 1960, Oswego was renamed "Lake Oswego" when it annexed part of neighboring Lake Grove.[7] The city has some nicknames including "Lake No-Negro",[13][14][15] "Lake Big Ego",[13] "Fake Oswego"[13][14] and "Fake Lost Ego".[14] Additionally, it was spoken of as Nimbyville during a planning-related seminar on 2008 by Dennis Egner.[16] A 2012 article in the Daily Journal of Commerce identified Egner as a long-range planning director for the city of Lake Oswego.[17] According to historian James W. Loewen, locals often call it "Lake No Negro" in reference to its recognition status as an "elite white suburb".[18]

In August 2020, Lake Oswego received significant media attention when its resident received an anonymous letter from neighbors asking them to take down their "Black Lives Matter" sign from the window, complaining that it lowers property values,[19][20][21] which prompted Mayor Studebaker to issue a response to this matter.[22] A documentary titled Lake No Negro about Lake Oswego's racially exclusive past was produced by a Lakeridge High School student in 2020[23]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 11.35 square miles (29.40 km2), of which 10.68 square miles (27.66 km2) are land and 0.67 square miles (1.74 km2) are covered by water.[24] That area does not include more than 1,100 acres (4.5 km2) of unincorporated land within the urban services boundary as defined by Clackamas County.[25] Oswego Lake is a lake, originally named Waluga (wild swan) by Clackamas Indians,[26] which has been expanded is and currently managed by the Lake Oswego Corporation.[27] The lake supports watercraft, and a dock floats at the lake's east end, where boaters can disembark and walk to the nearby businesses. The main canal from the Tualatin River was dug in 1872.[28]

Every three years, the water level in the lake is lowered several feet by opening the gates on the dam and allowing water to flow into Oswego Creek and on to the Willamette River, enabling lakefront property owners to conduct repairs on docks and boathouses.[29] In 2010, the lake was lowered about 24 feet (7.3 m) to allow for construction of a new sewer line, the lowest lake level since 1962, when the original sewer line was installed.[30]

The city extends up Mount Sylvania and through Lake Grove towards Tualatin.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 96 | — | |

| 1890 | 544 | 466.7% | |

| 1920 | 1,818 | — | |

| 1930 | 1,285 | −29.3% | |

| 1940 | 1,726 | 34.3% | |

| 1950 | 3,316 | 92.1% | |

| 1960 | 8,906 | 168.6% | |

| 1970 | 14,615 | 64.1% | |

| 1980 | 22,527 | 54.1% | |

| 1990 | 30,576 | 35.7% | |

| 2000 | 35,278 | 15.4% | |

| 2010 | 36,619 | 3.8% | |

| 2020 | 40,731 | 11.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[31] 2018 Estimate[32][4] | |||

2010 census

As of the census of 2010, there were 36,619 people, 15,893 households, and 10,079 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,428.7 inhabitants per square mile (1,323.8/km2). There were 16,995 housing units at an average density of 1,591.3 per square mile (614.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 89.3% White, 0.7% African American, 0.4% Native American, 5.6% Asian, 1.0% from other races, and 3.0% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 3.7% of the population.[5][25]

Of the 15,893 households, 28.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 53.1% were married couples living together, 7.4% had a female householder with no husband present, 2.9% had a male householder with no wife present, and 36.6% were not families. About 30.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.29 and the average family size was 2.88.[5]

The median age in the city was 45.8 years; 22.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 5.7% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 21% were from 25 to 44; 35.1% were from 45 to 64; and 16.2% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 47.3% male and 52.7% female.[5]

In the city, the population was distributed as 24.8% under the age of 18, 6.1% from 18 to 24, 26.8% from 25 to 44, 31.0% from 45 to 64, and 11.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.2 males. The median income for a household in the city was $71,597, and for a family was $94,587 ( Males had a median income of $66,380 versus $41,038 for females. The per capita income for the city was $42,166, and 3.4% of the population and 2.3% of families were below the poverty line. Of the total population, 2.0% of those under the age of 18 and 4.0% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.[5]

City government

The city has a council-manager form of government, which vests policy-making authority in an elected, volunteer city council. The council consists of a mayor and six councilors, all of whom are elected at-large and serve four-year terms.[33]

Day-to-day operations are handled by an appointed, professional city manager. Almost all of the city's employees, which include part-time staff amounting to about 342 full-time equivalents,[34] report to the city manager. This includes the police chief, fire chief, one assistant city manager, and the community development director. The biggest groups are:

- Police and fire departments, consisting of about 50 people each,

- Library, parks, and recreation departments, consisting of about 70 people total

- About 80 people throughout the engineering, planning, and maintenance departments

Ground was broken in 2019 on construction of a new city hall that would also house the city's police department and the Arts Council of Lake Oswego, on a site adjacent to the existing facility.[35] Located at A Avenue and Third Street, the new city hall opened to the public in April 2021.[36]

Civic involvement

Neighborhood associations play a formal role for citizen involvement in the city government's land-use planning and other activities. A neighborhood association's role is governed by state and city law. As of September 2013, the 21 recognized neighborhood associations (associations including lakefront property are marked with a ¤ symbol) include: Birdshill, Blue Heron ¤, Bryant ¤, North Shore-Country Club ¤, Evergreen ¤, First Addition, Forest Highlands, Glenmorrie, Hallinan Heights, Holly Orchard, Lake Grove, Lakewood ¤, McVey-South Shore ¤, Old Town, Palisades ¤, Rosewood, Skylands, Uplands, Waluga, Westlake, and Westridge.[37]

Oswego Lake

Oswego Lake has been a subject of controversy over whether it is a private lake or a public navigable water. A lawsuit against the city charges that they are preventing people from using a public stairway in a public park to swim in a public lake.[38] The City of Lake Oswego does not allow public access. Two recreational users of the lake who were barred from using the lake filed a lawsuit in 2012.[39] On August 1, 2019, the Oregon Supreme Court ruled that a 2012 Lake Oswego ordinance will need to be reviewed. The Supreme Court recognized public right to enter the body of water from public land and that the City of Lake Oswego cannot interfere with this right.[40]

Public schools

The Lake Oswego School District includes most of the city boundaries,[41][42] and serves roughly 7,000 students, with a ratio of 23 students per instructor. The two high schools in the district are Lake Oswego High School and Lakeridge High School. The six elementary schools and two junior high schools serve students in grades 1 through 8. The junior high schools are Lakeridge Junior High and Lake Oswego Junior High. Lakeridge Junior High was known as Waluga Junior High until 2012 when it was merged with Bryant Elementary.

A portion of Lake Oswego in Multnomah County is in Portland Public Schools.[42]

Cultural and recreational facilities

The city maintains 600 acres (2.4 km2) of parks and open spaces[43] including George Rogers Park, Millennium Plaza Park and Lake Oswego Golf Course.[44]

Lake Oswego has one public library, part of the Library Information Network of Clackamas County. From 2002 to 2006, the library was rated among the top 10 libraries serving similar population sizes in the United States.[45]

Economy

Largest employers

According to Lake Oswego's 2022 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[46] the principal employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lake Oswego School District | 813 |

| 2 | Mary's Woods at Marylhurst | 630 |

| 3 | Eye Health Northwest | 435 |

| 4 | Micro Systems Engineering | 406 |

| 5 | Logical Position | 380 |

| 6 | Axia Home Loan | 379 |

| 7 | City of Lake Oswego | 347 |

| 8 | Kindercare Education, LLC | 300 |

| 9 | Navex Global | 270 |

| 10 | Directors Mortgage, Inc. | 183 |

Notable people

- LaMarcus Aldridge (1985– ), former NBA player for the Portland Trail Blazers[47]

- Art Alexakis (1962– ), founder and lead singer of multiplatinum band Everclear

- Allen Alley (1954– ), Republican nominee for Oregon state treasurer in 2008, Republican candidate for Oregon governor in 2010

- Jon Arnett, NFL player and member of the College Football Hall of Fame[48]

- Luke Askew (1932–2012), actor.[49]

- Daniel Baldwin (1960– ), film actor, producer, and director[50]

- Nicolas Batum (1988– ), player for the Los Angeles Clippers[51]

- J. J. Birden (1965– ), NFL wide receiver[52]

- Frank Brickowski (1959– ), NBA player[53]

- Walter F. Brown (1926– ), Navy commander JAGC, judge, state senator, 2004 presidential candidate for the Socialist Party USA[54]

- Terry Dischinger (1940– ), basketball gold medalist in the 1960 Olympics and NBA player from 1962 to 1973[55]

- Mike Dunleavy Jr. (1980– ), Former NBA player[56]

- Mike Erickson (1963– ), businessman and candidate for U.S. Congress in 2006 and 2008[57]

- Rudy Fernández (1985– ), NBA player for the Portland Trail Blazers (2008–2011)[58]

- Stu Inman (1926–2007), co-founder of the Portland Trail Blazers[59]

- Alberto Leon (1998— ), Baseball catcher in the SBL

- Neil Lomax (1959– ), NFL quarterback 1981–88[60]

- Lopez Lomong (1983– ), U.S. Olympic Team track runner 2008 & 2012, and one of the Lost Boys of the Sudan[61]

- Stan Love (1949– ), player 1971–1975 and father of Kevin Love[62]

- Merrill A. McPeak (1936– ), former USAF chief of staff[63]

- Linus Pauling (1901–1994), winner of two Nobel prizes, in peace and chemistry; author and educator[64] (Ancestors of Pauling moved to Oswego in 1882.)[65]

- Julianne Phillips (1960– ), model, actress, former wife of Bruce Springsteen, co-star of 1990s TV series Sisters[66]

- Henry Selick (1952– ), stop-motion director and animator: The Nightmare Before Christmas, Coraline[67]

- William Stafford (1914–1993), U.S. Poet Laureate 1970–71[68]

- Drew Stanton (1984– ), NFL quarterback for the Arizona Cardinals[69]

- Salim Stoudamire (1982– ), professional basketball player

- Michael Stutes (1986– ), MLB relief pitcher for the Philadelphia Phillies[70]

- Nathan Farragut Twining (1897–1982), chairman of the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1957–1960[71]

- Yeat (2000– ), rapper[72]

Sister cities

Lake Oswego has two sister cities:

Yoshikawa, Saitama, Japan[73]

Yoshikawa, Saitama, Japan[73] Pucón, Araucanía Region, Chile

Pucón, Araucanía Region, Chile

See also

References

- "History". Lake Oswego Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- "Mayor and Council". City of Lake Oswego. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- "Census Population API". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- "City of Lake Oswego". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. March 11, 2008. Retrieved April 13, 2014.

- "A Brief History of Our City". Lake Oswego Public Library. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- "Eight Myths Concerning Lake Oswego". Oswego Heritage Council. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- Goodall, Mary (1958). Oregon's Iron Dream. Portland, Oregon: Binsford & Mort. p. 43.

- Kuo, Susanna Campbell. "A Brief History of the Oregon Iron Industry" (PDF). Oswego Heritage Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 19, 2008. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- "Petition of Intercity Buses, Inc., Wins Support of Oswego as PUC Hearing Ends". (December 22, 1954). The Oregonian, p. 8.

- "Oswego Fete Due Bus Line: Regular Service Set Next Monday". (February 3, 1955). The Oregonian, p. 8.

- Crotty, Jim (1997). How to Talk American: A Guide to Our Native Tongues. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 263. ISBN 0395780322. OCLC 36977188.

- Palahniuk, Chuck (2003). Fugitives & Refugees: A Walk in Portland, Oregon (1st ed.). New York: Crown Journeys. p. 21. ISBN 1400047838. OCLC 51058952. Retrieved November 9, 2021. Alt URL

- Cook, Curtis. "Portland Has the Highest Per-Capita Number of Nerds Who Say "Sportsball" for Any Athletic Activity". Willamette Week. Archived from the original on April 14, 2019. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

In a city affectionately nicknamed Lake No Negro

- "Confronting NIMBYs or Embracing a Difference of Opinion | Dartmouth College Planning". sites.dartmouth.edu. March 19, 2008. Archived from the original on April 14, 2019. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

Egner spoke about Nimbyville and how his office is focused on maintaining Lake Oswego's high quality of life.

- Fehrenbacher, Lee (April 24, 2012). "Lake Oswego wants to develop farm for urban agriculture, tennis courts". Daily Journal of Commerce. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- Loewen, James W. "Sundown Towns in the United States". sundown.tougaloo.edu. Archived from the original on June 23, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- Newton, Kamilah (August 25, 2020). "What are 'sundown towns'? Historically all-white towns in America see renewed scrutiny thanks to 'Lovecraft Country'". news.yahoo.com. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- "Neighbors ask Lake Oswego family to remove signage in support of Black Lives Matter". opb. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- Oregonian/OregonLive, Jayati Ramakrishnan | The (August 5, 2020). "Lake Oswego family receives racist letter over Black Lives Matter sign in window". oregonlive. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- Howell, Clara (August 25, 2020). "Lake Oswego mayor addresses recent interview about racism in the community". LakeOswegoReview. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- Zeller, Asia (May 21, 2020). "Behind the documentary 'Lake 'No Negro". LakeOswegoReview. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2012.

- "City population is up – what will that mean?". Lake Oswego Review. March 24, 2011. Archived from the original on February 22, 2013. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- Archived February 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Lake Oswego Corporation official website". Archived from the original on February 1, 2011. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- Corning, Howard McKinley (2004). Willamette Landings (3rd ed.). Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society. p. 195. ISBN 0-87595-042-6.

- Tims, Dana (October 31, 2006). "Drawdown under way to lower Oswego Lake". The Oregonian.

- Newell, Cliff (July 29, 2010). "Sewer project will make Oswego Lake disappear – briefly". Lake Oswego Review. Archived from the original on February 22, 2013. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- "Lake Oswego City Council website". Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- "Lake Oswego City 2019-2021 Budget" (PDF). Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Malee, Patrick (August 9, 2019). "Digging in: Lake Oswego breaks ground on new City Hall". Lake Oswego Review. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- Howell, Clara (April 9, 2021). "New Lake Oswego City Hall boasts welcoming, open environment". Lake Oswego Review. Archived from the original on April 9, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- "Planning: Neighborhood Associations". City of Lake Oswego website. Retrieved 2013-09-03

- "Meet the Heroes Suing to Free Oswego Lake, the Portland Area's Forbidden Paradise". wweek.com.

- Green, Aimee (August 1, 2019). "Oregon Supreme Court doesn't rule on central question: Is Oswego Lake private, or must it be open to all?". oregonlive.com. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- Stites, Sam (August 8, 2019). "Access pending? Oswego Lake debate will return to lower courts". LakeOswegoReview. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- U.S. Census Bureau Geography Division (December 18, 2020). 2020 Census – School District Reference Map: Clackamas County, OR (PDF) (Map). 1:204,700. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Multnomah County, OR" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- "Parks | City of Lake Oswego". www.ci.oswego.or.us. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- "Municipal Golf Course Renovation by Dan Hixson". fescue.github.io. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- "Hennen's American Public Library Ratings". Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- "City of Lake Oswego CAFR" (PDF). oswego.or.us.

- Quick, Jason (July 1, 2009). "'Faith' keeps LaMarcus Aldridge confident he'll stay with Blazers". The Oregonian. Retrieved July 1, 2009.

- Newell, Cliff. "Jaguar Jon Archived 2013-02-22 at archive.today." The Lake Oswego Review. January 31, 2008. Retrieved on December 6, 2012.

- Bailey, Everton Jr. (April 13, 2012). "Lake Oswego actor Luke Askew, featured in HBO's 'Big Love', 'Easy Rider' and others, dead at 80". The Oregonian. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- Bella, Rick (July 14, 2011). "Daniel Baldwin says volatile relationship grew worse after move to Lake Oswego". The Oregonian. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- Freeman, Joe (October 28, 2012). "Trail Blazers building blocks: Nicolas Batum, The Gamble". The Oregonian. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- Newell, Cliff. "Birden sees plenty of success after pro football career Archived 2013-02-22 at archive.today." The Lake Oswego Review. July 3, 2008. Retrieved on December 6, 2012.

- Canzano, John (February 9, 2013). "The rules for millionaire matchmaking with Greg Oden". The Oregonian.

- Mapes, Jeff (June 7, 2010). "Greens pick former state senator for treasurer, but no one yet for Oregon governor". The Oregonian. Retrieved June 7, 2010.

- Newell, Cliff. "Upward Basketball teaches b-ball to youngsters Archived 2013-02-22 at archive.today." The Lake Oswego Review. March 20, 2008. Retrieved on December 6, 2012.

- "Dunleavy joins Duke exodus." USA Today. May 11, 2002. Retrieved on February 6, 2009.

- Law, Steve. "Erickson takes GOP primary in 5th District Archived 2013-02-22 at archive.today." Lake Oswego Review. May 20, 2008. Retrieved on December 6, 2012.

- Eggers, Kerry. "Rudy excites fans and teammates Archived 2013-02-22 at archive.today." Portland Tribune. January 4, 2009. Retrieved on December 6, 2012.

- "OBITUARIES; Stu Inman, 80; helped assemble Portland's NBA champion team." Los Angeles Times. February 1, 2007. B9. Retrieved on February 13, 2009.

- Moore, Kenny. "This Phone Will Ring On Apr. 28." Sports Illustrated. April 27, 1981. 2 Archived 2012-07-17 at archive.today. Retrieved on February 13, 2009.

- Newell, Cliff (May 30, 2012)."Lopez Lomong: From Lost Boy to Olympian" Archived 2013-02-01 at archive.today. Lake Oswego Review. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

- "Stan Love Archived 2007-09-06 at the Wayback Machine." Willamette Week. July 7, 2004. Retrieved on February 13, 2009.

- "Lake Oswego general could make Kerry cabinet Archived 2004-12-16 at the Wayback Machine." Associated Press. Friday September 17, 2004. Retrieved on February 13, 2009.

- "Oswego Pioneer Cemetery plans Memorial Day celebration that links Lake Oswego's past with its present". May 27, 2011.

- "The Ancestry of Linus Pauling (The Paulings) - Pauling Chronology - Ava Helen and Linus Pauling Papers - Special Collections & Archives Research Center, Oregon State University Libraries".

- "Personalities Archived 2012-10-20 at the Wayback Machine." The Washington Post. August 6, 1988. C03. Retrieved on February 13, 2009.

- Hundhammer, Linda (April 2, 2009). "Making Movie Magic". Lake Oswego Review. Pamplin Media Group. Archived from the original on February 22, 2013. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- "Security, BY WILLIAM STAFFORD." Los Angeles Times. November 24, 1991. Book Review. Start Page: 6. Retrieved on February 13, 2009.

- Howell. "Drew Stanton, QB." Retrieved May 17, 2013.

- Michael Stutes Minor League Statistics & History. Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved on 2013-09-04.

- "Cultural Resources Inventory: C.W. Twining House" (PDF). City of Lake Oswego. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- Breihan, Tom (February 23, 2022). "Yeat Is The Future, Maybe". Stereogum. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- "Community: History and Culture". City of Lake Oswego website. Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved December 11, 2006.

External links

- Official website

- Historic photos of Lake Oswego from the City of Lake Oswego

- Lake Oswego from the Oregon Blue Book

- "Lake Oswego". The Oregon Encyclopedia.