Frances Grey, Duchess of Suffolk

Frances Grey, Duchess of Suffolk (née Lady Frances Brandon; 16 July 1517 – 20 November 1559), was an English noblewoman. She was the second child and eldest daughter of King Henry VIII's younger sister, Princess Mary, and Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk. She was the mother of Lady Jane Grey, de facto Queen of England and Ireland for nine days (10 July 1553 – 19 July 1553),[1] as well as Lady Katherine Grey and Lady Mary Grey.

Frances Grey | |

|---|---|

| Duchess of Suffolk | |

Effigy at Westminster Abbey | |

| Born | 16 July 1517 Hatfield, Hertfordshire, Kingdom of England |

| Died | 20 November 1559 (aged 42) London, Kingdom of England |

| Buried | 5 December 1559 Westminster Abbey |

| Noble family | Brandon |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Issue more... | Lady Jane Grey Katherine Seymour, Countess of Hertford Lady Mary Keyes |

| Father | Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk |

| Mother | Mary Tudor, Queen of France |

| Signature |  |

Early life and first marriage

Frances Brandon was born on 16 July 1517 in Hatfield, Hertfordshire, England.[2] Frances was an uncommon name at the time, as she was reportedly named after St. Francis of Assisi, although some historians believe she was named in honour of Francis I, the French king.[3]

She spent her childhood in the care of her mother, Mary Tudor, the youngest surviving daughter of Henry VII and younger sister of Henry VIII. For most of Frances’s childhood she resided in Westhorpe, Suffolk.[3] Her father, Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, who had been married at least twice before, obtained a declaration of nullity regarding his first marriage to Margaret Neville on the ground of consanguinity and secured a Papal bull from Pope Clement VII in 1528 to confirm his marriage to Mary Tudor, which legitimised Frances as his daughter.[4]

Frances was close to her aunt Catherine of Aragon, the first wife of her maternal uncle Henry VIII, and was a close childhood friend of her first cousin, the future Queen Mary I. She was so close to Catherine of Aragon that Catherine was made one of her godmothers, with her other godmother being Princess Mary. Frances and Mary spent a good deal of time together during their adolescence.

In 1533, Frances married Henry Grey, Marquess of Dorset.[5] The marriage took place at Suffolk Place, a mansion that belonged to her parents on the west side of Borough High Street in Southwark. It was this marriage, and her three children, which led to her life in the Tudor Court.[3]

Her first two pregnancies resulted in the births of a son – Henry (Lord Harington), and a daughter, who both died at an early age with unknown birthdates. Their births were followed by three surviving daughters:

- Lady Jane Grey (c. 12 October 1537 – 12 February 1554) – married Lord Guildford Dudley

- Lady Katherine Grey (25 August 1540 – 26 January 1568) – married Henry Herbert, Lord Herbert and later Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford

- Lady Mary Grey (c. 20 April 1545 – 20 April 1578) – married Thomas Keyes

Frances's residence at Bradgate was a minor palace in the Tudor style. After the deaths of her two brothers, the title Duke of Suffolk reverted to the crown, and was later granted to Frances's husband. Around 1541 Bishop John Aylmer was made chaplain to the duke, and tutor of Greek to Frances's daughter, Lady Jane Grey.[6]

At court

As the niece of Henry VIII, Frances was frequently at court. It was through her friendship with Catherine Parr that Frances' daughter Lady Jane Grey secured a place in the queen's household.[4] There, Jane met Henry VIII's son and future successor, Edward. Henry VIII died on 28 January 1547, and Edward VI succeeded to the throne. Jane followed Catherine Parr to her new residence and was established as a member of the inner circle for the nine-year-old king.

Frances and her sister Eleanor had been removed from succession in the will of King Henry VIII alongside the descendants of their aunt Margaret Tudor, though their daughters were still included following Edward's half-sisters Mary and Elizabeth. It is unclear as to these changes removing Frances from the line of succession.

Catherine Parr then married Thomas Seymour, 1st Baron Seymour of Sudeley and Lord High Admiral. Lady Jane followed her to her new household. Frances, her husband, and other members of the aristocracy saw Jane as a possible wife for the young King.

Catherine Parr died on 5 September 1548 which sent Jane back into the care of her mother. Thomas Seymour pressed the Suffolks with demands that he held Jane's wardship and she should be returned to his household. Jane returned to Seymour's household and moved into Catherine Parr's apartments. Seymour still planned to convince Edward VI to marry Jane, but the king had become distrustful of his two uncles. An increasingly desperate Seymour invaded the king's bedchamber in an attempt to abduct him, and shot Edward's beloved dog when the animal tried to protect its master. Not long after Seymour was tried for treason and executed on 20 March 1549. The Suffolks convinced the Privy Council of their innocence in Seymour's scheme. Jane was again recalled home. The Duke and Duchess lost hope of marrying her to the king, who was sickly and thought likely not to live. For a time it is claimed they contemplated marrying her to Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford, son of the Lord Protector and Anne Stanhope. However, the Lord Protector fell from power and was replaced by John Dudley.

In May 1553, Guildford Dudley, the second-youngest son of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, and de facto regent during the young Edward VI's minority, married Frances' daughter Jane. Frances and Henry Grey fully supported and pushed for this marriage between Guildford and Jane. The marriage would be uniting two powerful and Protestant families.[3] Her daughter Katherine was married to Henry Herbert, the son and heir of William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke, at Durham House. Dudley's daughter Katherine was promised to Henry Hastings, heir of the Earl of Huntingdon.[7] At the time they took place the alliances were not seen as politically important, even by the ambassador of the Holy Roman Empire Jehan de Scheyfye, who was the most suspicious observer.[7] Often perceived as proof of a conspiracy to bring the Dudley family to the throne,[8] they have also been described as routine matches between aristocrats.[9][10][11]

It has been claimed since the early 18th century that Lady Jane was brutally beaten and whipped into submission by the duchess. However, there is no evidence for it. Lord Guildford was, as a fourth son, not the greatest match for an eldest daughter of royal descent, and William Cecil, another close friend of the Suffolks, claimed the match was brokered by Catherine Parr's brother and his second wife.[12] According to Cecil, they promoted the match to Northumberland who responded rather enthusiastically. The Suffolks did not favour the match much since it would have meant passing the crown out of their family to Northumberland's. However, since Northumberland claimed to have the king's support in the matter, they finally gave in. The only historical proof of some family quarrel concerning the marriage is written down by Commendone as "the first-born daughter of the Duke of Suffolk, Jane by name, who although strongly deprecating the marriage, was compelled to submit by the insistence of her mother and the threats of her father".[13]

By June 1553, Edward VI was seriously ill. The succession of his Catholic half-sister Mary would compromise the English Reformation. Edward opposed Mary's succession, not only on religious grounds but also on those of legitimacy and male inheritance, which also applied to Elizabeth.[14] He drafted the Devise for the Succession, which passed over the claims of his half-sisters and settled the Crown on his cousin Jane Grey.[15] Like his late father, he also passed over Frances who otherwise would have been the heir presumptive, possibly because she seemed quite unlikely at her age to produce a son to succeed her.

Frances and her husband were at first outraged, but eventually, after a private audience with the king, she renounced her own rights to the throne in favour of Jane,[16] approving the plan for the succession.[4]

Queen's mother

Edward VI died on 6 July 1553. Lady Jane was declared queen on 10 July. The duchess joined her for the proclamation and during her stay in the Tower. She had been fetched when Northumberland realised Jane's confusion and overwhelming feelings, and she managed to calm her daughter down. Since she had seen the king himself and spoken to him about the succession, she could convince Jane that she was the rightful queen and heir.[18] Their success was short-lived. Jane was deposed by armed support in favour of Mary I on 19 July 1553.

The Duke of Suffolk was arrested, but released days later thanks to the duchess's intervention. The moment she heard of her husband's arrest, she rode over to Mary in the middle of the night to plead for her family. Despite all odds, not only did the duchess manage to be received by the queen, but also could secure him a pardon by placing all the blame on Northumberland. While in his household, Lady Jane had fallen sick of food poisoning and had suspected Northumberland's family.[19] The duchess now used her daughter's suspicions and her husband's sickness to accuse Northumberland of having tried to kill her family.[20] Therefore, Mary was willing to pardon the Duke of Suffolk. She intended to pardon Jane once her coronation was complete, sparing the 16-year-old's life.

However, Wyatt the Younger declared a revolt against Mary on 25 January 1554. The Duke of Suffolk joined the rebellion, but was captured by Francis Hastings, 2nd Earl of Huntingdon. The revolt had failed by February. The plot ringleaders had wished to supplant Mary with her half-sister Elizabeth, although Elizabeth played no part in the matter. After the attempt to put Jane on the throne Frances was confined in the Tower of London for a time.[5] Jane was now becoming too dangerous for Mary, and was beheaded on 12 February 1554 with her husband. Jane's father was convicted of high treason and was executed eleven days later on 23 February 1554. With two young daughters barely in their teens and her husband a convicted traitor, the duchess faced ruin. As a wife, she held no possessions in her own right. All her husband's possessions would return to the Crown, as usual for traitors' property. She managed to plead with the queen to show mercy, which meant at least she and her daughters had the chance of rehabilitation. The queen's forgiveness meant some of Suffolk's property would remain with his family, or at least could be granted back at some later time.[21]

Second marriage and death

Frances lived in poverty during the reign of Mary I.[5] Mary I made a point of placing her by her side, favoured but kept under the observation of the queen. She was still regarded with some suspicion and in April 1555 the Spanish ambassador, Simon Renard, wrote of a possible match between Frances and Edward Courtenay, a Plantagenet descendant.[22]

Once again, their children would have had a claim to the throne, but Courtenay was reluctant, and Frances escaped the marriage by another, much safer match. She married her Master of the Horse, Adrian Stokes.[23] It was a safe marriage for her, since any children from it would be considered too low-born to compete for the throne. Her childhood friend and stepmother Katherine Willoughby had married her gentleman usher, so Frances moved on familiar ground. She and Stokes married in 1555.[24] Three children were born to the couple:

- Elizabeth Stokes (20 November 1554), stillborn

- Elizabeth Stokes (16 July 1555 – 7 February 1556?), may have died in infancy

- A son (December 1556), stillborn

On 21 November 1559, Frances Grey died due to illness. Her remains were transferred from Richmond to Westminster Abbey where the funeral was held on 5 December. During the funeral service, her daughter Katherine participated as head mourner. The funeral was the first Protestant service performed in Westminster Abbey. Four years after her death, her husband erected an alabaster monument (this is most likely created by Cornelius Cure) and crowned the grave with Frances' effigy which still remains. Her effigy had an ermine-lined mantle over the dress with a pendant around her neck. She lies on mattress with a lion at her feet and her coronet has been repaired and gilded.[25] The inscription on her grave reads in Latin:

- Nor grace, nor splendor, nor a royal name,

- Nor widespread fame can aught avail;

- All, all have vanished here.

- True worth alone Survives the funeral pyre and silent tomb[26]

Reputation

Frances Grey's posthumous reputation for being insensitive or cruel is largely based on Roger Ascham's account of a statement of her daughter Jane:

For when I am in presence of either Father or Mother, whether I speak, keep silence, sit, stand or go, eat, drink, be merry or sad, be sewing, playing, dancing or doing anything else, I must do it, as it were, in such weight, measure and number, even so perfectly as God made the world, or else I am so sharply taunted, so cruelly threatened, yea, presently sometimes with pinches, nips and bobs, and other ways, (which I shall not name, for the honour I bear them), so without measure misordered, [sic] that I think myself in hell.[27]

From this passage it is often deduced that Frances and Henry Grey had mistreated their daughter. However, Ascham wrote these words years after the actual meeting, and his view might have been influenced by the later events concerning the Greys. The letter he wrote to Jane just a few months after the visit speaks admiringly of her parents and praises both Jane's and their virtues.[28] James Haddon, chaplain of the Greys, told his acquaintance Michel Angelo Florio how Jane was following in her parents' footsteps concerning piety, and how close she was to her mother Frances.[29]

The alleged abuse of her daughter as well as her role in the machinations to bring Jane the crown are the subject of historical debate. While Jane was already with her husband Guildford Dudley, under the supervision of his parents, she heard news that Edward VI was changing his will to exclude her mother from the succession and name Jane as his heir instead. Jane, startled by the news, asked her mother-in-law permission to visit her mother, yet was met with refusal. Ignoring her, Jane sneaked out of the house and went back home.[16] Jane's mother was accused of having beaten Jane into submission to marry Guildford Dudley.

When Grey's brother-in-law's children Thomas, Margaret and Francis Willoughby were orphaned, the Greys took them under their wings. Thomas soon joined Henry and Charles Brandon at college and his siblings went to live with their uncle George Medley. However, during the Wyatt rebellion, Medley was imprisoned and taken to the Tower. At the time he was released, the imprisonment had taken its toll on him and he couldn't take care of the children any longer. Frances had already lost her eldest daughter, her husband and a considerable part of her lands. Nevertheless, she once more resumed care of Francis and Margaret Willoughby, organised a place in school for the boy and took the girl to court, along with herself and her surviving daughters.[30]

Their elder brother was placed as ward under a councillor's care. Since Thomas was his father's heir, the councillor had control over the Willoughby fortune during Thomas's minority.

Dramatic representation

Frances, Duchess of Suffolk was portrayed by Sara Kestelman in the 1986 film Lady Jane and by Julia James in a 1956 episode of the BBC's Sunday Night Theatre. In an upcoming 2023 television series, My Lady Jane, Frances Grey will be portrayed by actress Anna Chancellor[31]

References

- Williamson, David (2010). Kings & Queens. National Portrait Gallery Publications. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-85514-432-3

- "Frances Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk & family". Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- Taylor, Alexander (4 July 2018). "Frances Grey, Duchess of Suffolk (1517–1559)". TudorSociety.com. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- O'Day, Rosemary. The Routledge Companion to the Tudor Age, Routledge, 2012 ISBN 9781136962530

- ""Frances Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk", Westminster Abbey". Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Mendle, Michael. Dangerous Positions; Mixed Government, the Estates of the Realm, and the Making of the "Answer to the xix propositions, University of Alabama Press, 1985. p. 61

- Loades, David (1996): John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland 1504–1553. Clarendon Press. 1996, ISBN 0-19-820193-1, pp. 238–239

- Ives, Eric (2009). Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-4051-9413-6.

- Jordan, W.K., and M.R. Gleason (1975): The Saying of John Late Duke of Northumberland Upon the Scaffold, 1553. Harvard Library. pp. 10–11, LCCN 75-15032

- Wilson, Derek (2005): The Uncrowned Kings of England: The Black History of the Dudleys and the Tudor Throne. Carroll & Graf. 2005. pp. 214–215; ISBN 0-7867-1469-7

- Christmas, Matthew. "Edward VI", History Today, Issue 27. March 1997

- Leanda de Lisle: The Sisters who would be Queen, p. 98

- De Lisle, p. 329

- Starkey, David (2001), Elizabeth. Apprenticeship, London: Vintage, 2001, ISBN 0-09-928657-2, pp. 112–113

- Ives 2009, p. 321.

- De Lisle, p. 104

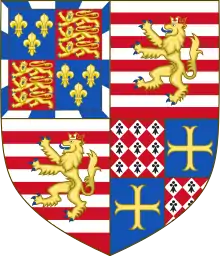

- Sodacan (21 February 2015), English: Arms of Frances Grey, Duchess of Suffolk, retrieved 17 May 2020

- De Lisle, p. 110

- Leanda de Lisle, p. 105

- De Lisle, p. 126

- De Lisle, p. 157

- Calendar State Papers Spain, vol. 13 (1954), no. 177

- Franklin-Harkrider, Melissa (2008). Women, Reform and Community in Early Modern England: Katherine Willoughby, Duchess of Suffolk, and Lincolnshire's Godly Aristocracy, 1519–1580. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-365-9.

- Ives 2009, p. 38.

- "The History of Westminster Abbey by John Flete", The History of Westminster Abbey, Cambridge University Press, pp. 33–138, 19 May 2011, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511975554.003, ISBN 9781108072946, retrieved 1 April 2023

- De Lisle, p. 197

- De Lisle, p. 68

- De Lisle, p. 17

- De Lisle, p. 159

- De Lisle, p. 162

- https://press.amazonstudios.com/us/en/press-release/hear-ye-hear-ye-prime-video-unveils-additional-cas