Xin Zhui

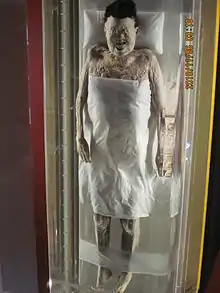

Xin Zhui (Chinese: 辛追; [ɕín ʈʂwéɪ]; c. 217 BC–168 or 169 BC), also known as Lady Dai or the Marquise of Dai, was a Chinese noblewoman. She was the wife of Li Cang (利蒼), the Marquis of Dai, and Chancellor of the Changsha Kingdom, during the Western Han dynasty of ancient China. Her tomb, containing her well-preserved remains and 1,400 artifacts, was discovered in 1971 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan, China. Her body and belongings are currently under the care of the Hunan Museum;[1] artifacts from her tomb were displayed in Santa Barbara and New York City in 2009.[2][3] Her body is notable as being one of the most well preserved mummies ever found.[2]

Xin Zhui | |

|---|---|

| Marquise of Dai | |

A wax sculpture reconstruction of Xin Zhui | |

| Dynasty | Han dynasty |

| Born | c. 217 BC |

| Died | 168 or 169 BC (aged 48–49) |

| Buried | Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan Province, China |

| Husband | Li Cang (利蒼), Marquis of Dai and Chancellor of Changsha Kingdom |

| Xin Zhui | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 辛追 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Life

Xin Zhui lived a grand lifestyle for her time. She had private musicians for entertainment who would play for her parties as well as for her personal amusement.[4] She may have enjoyed playing music as well, particularly the guqin, which was traditionally associated with refinement and intellect.[1][lower-alpha 1] As a noble, Xin Zhui also had access to a variety of imperial foods, including various types of meat, which were reserved for the royal family and members of the ruling class.[6] Most of her clothing was made of silk and other valuable textiles, and she owned many cosmetics.[4]

As she aged, Xin Zhui suffered from many ailments that eventually led to a heart attack that killed her. Along with schistosomiasis, a parasitic infection, she also had coronary thrombosis and arteriosclerosis, most likely linked to excessive weight gained due to a sedentary lifestyle, diabetes, angina pectoris, liver disease, and hypertension. Lumbago and a compressed spinal disc probably caused her immense pain, which contributed to a decrease in physical activity. She also suffered from gallstones, one of which lodged in her bile duct and further deteriorated her condition. Her arteries were almost totally clogged.[7][2][8]

A total of 138 melon seeds were found in her stomach, intestines, and esophagus; researchers believed she gulped down the melon in a great haste.[7] It is inferred that she died in summer, when fruits and melons ripen. The presence of melon seeds in her stomach also indicates that she died within two to three hours after eating the fruit.[9]

Xin Zhui died around 50 years of age in 168 or 169 BC.[4][7]

Discovery

In 1968, workers digging an air raid shelter for a hospital near Changsha unearthed the tomb of Xin Zhui, as well as the tombs of her husband and a young man who is most commonly thought to be her son.[4] With the assistance of over 1,500 local high school students, archaeologists began a large excavation of the site beginning in January 1972. Xin Zhui's body was found within four rectangular pine constructs that sat inside one another which were buried beneath layers of charcoal and white clay. The corpse was wrapped in twenty layers of clothing bound with silk ribbons.[10]

In the tomb of Xin Zhui, four coffins of decreasing sizes enclosed one another. The first and outermost coffin is painted black, the color of death and the underworld. All painted images sealed inside this coffin were thus designed not for an outside viewer but for the deceased and concern the themes of death and rebirth, protection in the afterlife, and immortality. The second coffin has a black background but is painted with a pattern of stylized clouds and with protective deities and auspicious animals roaming an empty universe. A tiny figure, the deceased woman, is emerging at the bottom center of the head end. Only her upper body is shown, for she is about to enter this mysterious world. The third coffin exhibits a different color scheme and iconography. It is shining red, the color of immortality, and the decorative motifs include divine animals and a winged immortal flanking three-peaked Mount Kunlun, which is a prime symbol of eternal happiness. Inside this tomb on top of the fourth and innermost coffin the excavators found a painted silk banner about two meters long.

Yellow and black feathers are stuck on the cover board of the coffin.[11] The feathers stuck to the coffin were expressing the hopes that Xin Zhui would grow feathers on the body and enter the heavens to become immortal.

Xin Zhui's body was remarkably well preserved in an unknown fluid inside the coffin. Her skin was soft and moist, with muscles that still allowed for her arms and legs to flex at the joints. All her organs and blood vessels were also intact, with small amounts of Type A blood being found in her veins. There was hair on her head, with a wig pinned with a hair clasp on the back of her head. There was skin on her face, and her eyelashes and nose hair still existed. The tympanic membrane of her left ear was intact, and her finger and toe prints were distinct. This preservation allowed doctors at Hunan Provincial Medical Institute to perform an autopsy on 14 December 1972.[10] Much of what is known about Xin Zhui's lifestyle was derived from this and other examinations. As a member of the nobility, her body would have been washed with fragrant water and wine, which has antibacterial properties.[12] Xin Zhui's body was soaked in an unknown liquid that was acidic, which may have helped preserve the body by preventing bacteria from growing.[12] Many scientists believe that the fluid is water from the body, rather than liquid poured into the coffin.[12]

More than 1,400 precious artifacts were found with Xin Zhui's body[2] including a wardrobe containing 100 silk garments, 182 pieces of expensive lacquerware, makeup and toiletries and 162 carved wooden figurines representing servants.[13][4] In Western Han Dynasty, elaborate and lavish burials were common practice; it was believed that another world, or afterlife, existed for the dead, and they needed food and accommodation just like the living and the necessities in life should be brought into the grave for use in the afterlife. The importance of filial piety during that time also resulted in a lavish burial with many artifacts.

Preservation

Scientists believe that three major factors helped preserve her body. First was the careful preparation of the body for burial, which slowed early stage of decomposition.[12] Second, the body was placed in an airtight set of coffins.[12] Lastly, the burial chamber was positioned deep underground, surrounded by charcoal and white clay. Water and air did not leak in and the temperature stayed constantly cool.[12] However, scientists do not know for certain what combination of factors helped preserve Xin Zhui's corpse, or why similar conditions failed to preserve other bodies.[12]

Other "Mawangdui-Type" cadavers in similar conditions have been found in China. Two from the same time period as Xin Zhui; they belong to a male official named Sui Xiaoyuan found in Jingzhou and a noblewoman named Ling Huiping found in Lianyungang. No consistent pattern explained why their bodies were preserved. All three had coffins containing liquid. However, Lady Dai's was acidic, whereas others' were alkaline, which would have aided bacterial growth. The tombs were also dug to different depths, from 5 metres (16 feet) to 16 metres (52 feet) and contained differing amounts of charcoal and white clay. In addition, similar airtight and watertight coffins failed to keep other cadavers from decomposing into skeletons or dust.[12]

Significance

Besides having some of the best preserved human remains ever discovered in China, the contents of Xin Zhui's tomb revealed much information about life in the Han dynasty that was previously unknown. The discovery continues to advance the fields of archaeology and science in the 21st century, particularly in the area of preservation of ancient human remains. Scientists in 2003 developed a "secret compound" that was injected into Xin Zhui's still existing blood vessels to assure her preservation.[10]

Her funerary banner had Han dynasty religious art motifs on it.[14] The woman on the top is possibly Xin Zhui herself drawn in imitation of Nüwa or the snake-like spirits next to her who could have been inspired by Nüwa, in the process of becoming a xian.[14]

See also

Notes

- Although traditional literature associates the playing of the qin as being a masculine activity, contemporary paintings and other artifacts strongly suggest that women enjoyed playing the instrument as well.[5]

References

- "The Exhibition of "Noble Tombs at Mawangdui" attracts interesting in New York". Hunan Museum. 5 March 2009.

- MANNING, SUE (20 September 2009). "Lady Dai tomb among richest finds in China history". Associated Press.

- "Exhibition: Ancient China". University of California, Santa Barbara. 19 September 2009.

- Bonn-Muller, Eti (May 2009). "Entombed in Style". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America.

- Thompson, John. "Women and the Guqin". silkqin.com.

- "There's 'nothing more important than food'". South China Morning Post. 3 March 2010.

- Cheng, Tsung O. (April 2012). "Coronary Arteriosclerotic Disease Existed in China Over 2,200 Years Ago". Methodist Debakey Cardiovascular Journal. United States National Library of Medicine. 8 (2): 47–48. doi:10.14797/mdcj-8-2-47. PMC 3405812. PMID 22891129.

- Scharping, Nathaniel (5 February 2017). "The Eternal Mummy Princesses". Discover.

- Amare, Verity (5 November 2021). "Blood in Her Veins: 2,000-Year-Old Mummy Looks Like She Recently Died". Medium.

- Bonn-Muller, Eti (10 April 2009). "China's Sleeping Beauty". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America.

- Spungen, Ella (7 August 2018). "Shipwrecks, Mummies, and Spoils: How (Almost) 6 Ancient Masterpieces Were Discovered Accidentally". Artspace.

- Liu-Perkins, Christine (8 April 2014). At Home in Her Tomb: Lady Dai and the Ancient Chinese Treasures of Mawangdui. Charles Bridge Publishing. ISBN 9781607347255 – via Google Books.

- Petkar, Sofia (2 December 2016). "World's best preserved mummy still has own hair and teeth at 2,100 years old". Metro.

- Cook, John S.; Major, Constance A. (19 September 2016). Ancient China: A History (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 229. doi:10.4324/9781315715322. ISBN 978-1-315-71532-2.