Lötschberg Base Tunnel

The Lötschberg Base Tunnel (LBT) is a 34.57 km (21.48 mi) railway base tunnel on the BLS AG's Lötschberg line cutting through the Bernese Alps of Switzerland some 400 m (1,300 ft) below the existing Lötschberg Tunnel. It runs between Frutigen, Berne, and Raron, Valais.

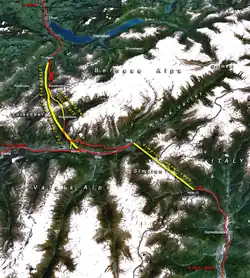

The Lötschberg Base Tunnel together with the century-old Simplon Rail Tunnel form the western part of the NRLA project (yellow: major tunnels, red: existing main tracks, numbers: year of completion) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Official name | German: Lötschberg Basis Tunnel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line | Lötschberg Line | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Traversing the Bernese Alps in Switzerland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 46.578°N 7.649°E – 46.309°N 7.832°E | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System | BLS, SBB CFF FFS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Start | Frutigen, canton of Bern, 780 m (2,560 ft) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| End | Raron, canton of Valais, 654 m (2,146 ft) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Work begun | 5 July 1999 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 14 June 2007 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | BLS NETZ AG | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | BLS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traffic | Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Character | Passenger, Freight | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Length | 34.5766 km (21.4849 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No. of tracks | One single-track tube for 20km, two single-track tubes for 14km | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) (standard gauge) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrified | 15 kV 16.7 Hz | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating speed |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Highest elevation | 828 m (2,717 ft) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lowest elevation | 654 m (2,146 ft) (south portal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Grade | 3–13 ‰ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Route map | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Lötschberg Base Tunnel was built as one of the two centrepieces of the NRLA project (the New Railway Link through the Alps). Construction of the LBT commenced in 1999 and achieved breakthrough during 2005. A ceremony to mark its completion was held in June 2007; the first train operations began in December 2007. Within only a few years of opening, the LBT had become saturated because of a 21 km (13 mi) single-track section present; without the completion of the second bore, its overall capacity has been greatly reduced. During 2016, a planning contract was awarded for the completion of the second track of the LBT, which has been estimated to cost 1 billion Swiss francs. The resulting plan was presented in Spring 2019. A decision between a full or partial completion of the second tube of the Lötschberg Base Tunnel is expected in 2023.[2][3][4]

Construction

Initial construction

The LBT was principally constructed to ease lorry traffic on the Swiss road network by providing faster routes for rail-based freight as an alternative. Reportedly, between the 1980s and 2000s, traffic on the north-south European axis (North Sea Ports to/from Northern Italy and along the Blue Banana) had increased more than tenfold, necessitating infrastructure investments to better cope with rising demands.[5] Accordingly, the LBT allows a substantial number of trucks and trailers to be loaded onto trains in Germany, pass through Switzerland on rail and be unloaded in Italy (rolling highway or trailer-on-flatcar respectively). It also cuts down travel time for German tourists going to Swiss ski resorts, and puts the Valais into commuting distance to Bern by reducing travel time by 50%. The total cost was SFr 4.3 billion (as of 2007, corrected to 1998 prices). This and the Gotthard Base Tunnel are the two centerpieces of the Swiss NRLA project.[6][7]

In 1994, early drilling was conducted in the area.[5] During 1999, full-scale construction work on the LBT commenced.[8][9] It was largely excavated using a combination of traditional techniques, including drilling and blasting. Roughly 80% of the tunnel was built using these conventional practices.[8] The remaining 20% was excavated using tunnel boring machines (TBMs). The excavation work was conducted from both the north and south portals.[8] During April 2005, the construction process reached a milestone when breakthrough was achieved; the event was attended by 1,000 guests.[5] The excavation process reportedly used 15 thousand kilograms (16 short tons) of explosives, while the material extracted would have filled a freight train that was 4,000 kilometres (2,500 mi) in length.[5] Work over the following year centered on the fitting-out process, installing all of the operational systems, including the track itself.[8]

In July 2006, track construction in the LBT was declared complete. Extensive testing then took place, including more than 1,000 test runs, which focused among other things on the use of the ETCS Level 2 system. Once satisfied that all systems had been validated, an official opening ceremony for the LBT was held during June 2007; at this event, the tunnel was recognised as the longest land tunnel anywhere in the world.[10][11][12] The LBT overran its budget of roughly $2.7 billion by around $840 million, which has impacted its operation.[5]

On 9 December 2007, the LBT was declared operational.[13] Initially, only regular freight services traversed the LBT, along with a minority of international and InterCity passenger trains (without stops between Spiez and Brig); passenger trains continued to operate on the old timetable (the travel time between Spiez and Brig was considered to be 56 minutes until December 2007, even if actual travel time through the LBT was only about 30 minutes). Since February 2008, the LBT has been routinely used for normal InterCity routes. Travel time between Visp and Spiez is about 28 minutes, of which 16 minutes is spent inside the LBT.

Additional phases

As a consequence of spiraling costs attributable to the overall NRLA project, it was decided to redirect funds from the Lötschberg tunnel to the Gotthard Base Tunnel. This funding decision leaves the LBT in a partially-completed state for a protracted period. Once fully complete, the LBT will consist of two single track bores side by side from portal to portal, connected about every 300 m (980 ft) with cross cuts, enabling the other tunnel to be used for escape.[14]

Currently, from South to North, a third of the tunnel is double track, a third is single track with the second bore in place but not equipped, and a third is only a single track tunnel with the parallel exploration adit providing the emergency egress. This unused western bore has been used by maintenance crews as a means of accessing the active eastern tunnel; an adjacent exploratory bore driven during the early 1990s has also proved useful for such purposes.[8]

The construction process was divided into three phases, of which only phase one has been completed to date:

- Phase one: construction of about 75% of the length of the West tube and the complete East tube of the main tunnel, the Engstlige tunnel, the two bridges across the Rhône, and the branch bore from Steg. Tracks are laid in the Eastern tubes of the LBT and Engstlige tunnels, and for some 12 km (7.5 mi) in the western tube of LBT, starting from the South.

- Phase two: laying of tracks in the bored but not equipped part of the western tube of LBT, and in the western tube of Engstlige tunnel.

- Phase three: construction of the remaining 8 km (5.0 mi) of the western tube, laying tracks on the Steg branch, and connection of this branch to the main line Brig-Lausanne, but towards Lausanne.

Phases two and three may be performed concurrently or separately. The cost of completing work on the LBT has been estimated to be around one billion Swiss francs.[15] The project also includes two parallel bridges over the river Rhône in canton Valais, the 2.6 km (1.6 mi) Engstlige tunnel (built with cut-and-cover method; the two tracks are separated by a wall). A planning contract for phases two and three was awarded in 2016 to the Swiss engineering consortium IG Valbt, headed by SRP Ingenieur.[15] The resulting plan was presented for review in early 2019,[8] and a decision between funding only Phase two or both Phase two and three is expected in 2023. The first option is naturally cheaper and is two years faster, but it provides a much lower capacity and requires an eight months full closure of the line.[2]

Operation

Its owner, BLS NETZ AG, presents the LBT as one of the safest, most modern and most technically complex rail tunnels in the world.[6] The company has attributed the tunnel's congestion to the combination of the rapid growth of passenger and freight traffic with the presence of a single track section, which severely limits its overall capacity; it views the implementation of double-track running as being "absolutely essential". Operation of the LBT allegedly has an impact on the timetable reliability and flexibility across the entire Swiss rail network, as well as facilitating a reduction in production costs via the freight traffic it carries.[6]

The 21 kilometres (13 mi) of single track, which lack passing loops, greatly complicates operations. Despite its relatively recent completion date, the LBT has already become a major bottleneck for rail freight traversing the Alps.[8][6] Typically, trains using the LBT are scheduled together in batches that run in each direction separated by long intervals; trains more than seven minutes late are either routed via the old line or must wait for the next available timetable slot in their direction in the LBT, incurring long further delays in either case.[13] By 2019, around 110 trains per day were using the LBT, while a further 66 have continued to use the old mountain tunnel largely due to the base tunnel's current capacity constraints. Of these 110, 30 were passenger services and 80 were hauling various types of freight, including intermodal freight transport and long-distance heavy freight trains. Heavy freight trains up to a maximum weight of 3,600 tonnes (4,000 short tons) and a maximum length of 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) have to use the LBT, as they are above the maximum gauge of the pre-existing mountain track. By 2017, the LBT reportedly facilitated the movement of 35.7 million gross tonnes (79 billion pounds) of rail freight.[8]

The LBT is operated and monitored from a dedicated control centre based at nearby Spiez.[13] The tunnel incorporates various measures for handling emergency situations; for use in such circumstances, a pair of intermediate access tunnels connect with the main bores at a series of underground emergency stations. Trains can also be moved between the two bores via multiple cross-over links spread throughout its length.[7]

On 13 March 2020, the second bore of the LBT was temporarily closed to all traffic following the discovery of ingress by both water and sand while remedial work was performed to address this.[16] In addition to cleaning the tunnel interior, removing the sand and excess water via suction, and the flushing out of its drainage system, temporary steel tanks have been installed in the bore with regular inspections of the tunnel with a particular focus on this issue. Furthermore, solutions to prevent reoccurrence in the long term have been identified and are to be compiled into a plan for approval by the Federal Office for Transport during late 2020; if approved, sections of the LBT shall be modified accordingly.[16] On 27 April 2020, it was announced that the LBT had been fully reopened.[17]

Travel speeds

- Regular freight trains: 100 km/h (62.1 mph)

- Qualified freight trains: 160 km/h (99.4 mph)

- Passenger trains: 200 km/h (124.3 mph)

- Tilting passenger trains: 250 km/h (155.3 mph)

Geothermal energy

Warm groundwater continuously drains from the LBT. The warmth of this water flowing out of the tunnel is used to heat the Tropenhaus Frutigen, a tropical greenhouse producing exotic fruit, sturgeon meat and caviar.[18]

See also

Notes and references

- Atlas, High-Speed Rail 2021 on the International Union of Railways (UIC) website.

- "Lötschberg Base Tunnel Upgrade Enters Next Stage". railway-news.com. 12 August 2020.

- "BLS erhält Plangenehmigungsverfügung für den Teilausbau des Lötschberg-Basistunnels – 13.06.2022 – BLS AG". BLS. October 18, 2016.

- "BLS is upgrading the Lötschberg Base Tunnel – BLS Ltd". BLS. August 18, 2016.

- "Tunnel under Alps links north, south Europe". NBC News. 28 April 2005.

- "Lötschberg Base Tunnel: a new Alpine rail link to connect Europe". BLS AG. 18 August 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Vuilleumier, F.; Teuscher, P.; Beer, R. (July 1997). "The Lötschberg railway base tunnel". Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology, Volume 12, Issue 3. 12 (3): 361–368. Bibcode:1997TUSTI..12..361V. doi:10.1016/S0886-7798(97)00034-5.

- Reynolds, Patrick (21 March 2019). "Lötschberg plans full rail baseline finish". tunneltalk.com.

- Teuscher, Peter and Hufschmied, Peter. (January 2000). "Lötschberg Base Tunnel - Start of Construction Work". IABSE Congress Report. 16 (4): 1705–1714. doi:10.2749/222137900796314464. ISBN 3-85748-101-3.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Klapper, Bradley S. (16 June 2007). "Swiss Open World's Longest Land Tunnel". Washington Post. Retrieved 11 May 2010.

- "Huge Swiss tunnel opens in Alps". BBC News. 15 June 2007. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- TSR Journal 15 June 2007, édition du 19h30.

- "The Lötschberg enters operation". alptransit-portal.ch. 8 December 2007.

- "Gotthard: From Dream to Nightmare". Temps Present. 24 May 2007.

- Green, Anitra (1 February 2016). "Planning contract awarded for Lötschberg Base Tunnel track doubling". railjournal.com.

- Sapién, Josephine Cordero (22 April 2020). "Lötschberg Base Tunnel to Open Again Following Water and Sand Ingress". railway-news.com.

- "Lötschberg base tunnel reopened after water ingress mitigated". Railway Gazette. 27 April 2020.

- Hufschmied, Peter and Andreas Brunner (1 October 2010). "The exploitation of warm tunnel water through the example of the Lötschberg Base Tunnel in Switzerland / Nutzung warmer Tunnelwässer am Beispiel des Lötschberg‐Basistunnels in der Schweiz". Geomechanics and Tunnelling. Geomechanics and Tunneling. 3 (5): 647–657. doi:10.1002/geot.201000045. S2CID 110175333.

External links

- Official project site

- Official site of the "ARGE Bahntechnik Lötschberg" the general contractor for the railway technology

- AlpTransit Portal of the Swiss Federal Archives

- Site with a movie documentation about the engineering and the works (railway technology)

- Rail Technology in the Lötschberg Base Tunnel

- Image Gallery on a contractors site