Léon Gard

Léon Gard (12 July 1901 - 12 November 1979) was a French painter and art critic.

Léon Gard | |

|---|---|

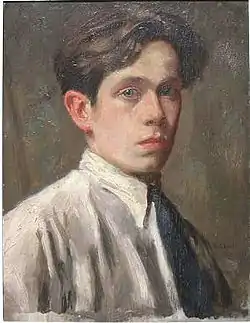

Self-portrait, 1925 | |

| Born | Léon Gard 12 January 1901 |

| Died | 12 November 1979 (aged 78) |

| Nationality | French |

| Education | École nationale des Beaux-Arts, Paris |

| Known for | Painting |

| Patron(s) | Louis Metman |

Biography

Early years

Gard was born in Tulle, Limousin. His family moved to Morigny, Normandy, and then to the 13th arrondissement of Paris. Gard at an early age started to express his artistic gifts. In 1913, at the age of twelve he drew a self-portrait in charcoal. Two years later he wrote to Louis Metman, the curator of the Museum of Decorative Arts, who took him under his wing and enrolled him in the Académie Ranson. He found a job as a notarial clerk. At sixteen, he copied old paintings for a play, Petite reine (the story of an antique dealer and a forger), adapted by Gabriel Signoret whose portrait he later painted.

Gard was seventeen when he exhibited for the first time in the Salon d'Automne (Autumn Gallery) with his portrait of Metman. He received a special award and was proposed as a member. This early success was not repeated and Gard later said ironically: "Was my work so bad, or were these gentlemen of the jury carried away by the wine? Who will ever know? In any case, if they made an error on that day, they corrected it afterwards."

1920s and 1930s

In 1922, he entered the National School of Art in Paris (headed by Ernest Laurent), but he clashed with his professors and the school's atmosphere:

agitated, noisy, in an ivory tower, giving itself airs of having the bit between the teeth, of being the safekeeper of authority, but actually destroying only art that nobody, in this majestic enclosure, thinks of defending, always making storms in a teacup or shouting "Fire!", the only real principle of this academy of mediocrities.

As for his masters, he wanted to recognize only the Old Masters and, especially, those Leonardo da Vinci called "the mistress of the masters": nature.

He caught the eye of Albert Besnard . He failed the Rome Grand Prix, but he received the Chenavard prize.

When he left school "by the Bonaparte route" (that is, by failing), he signed a contract with an art dealer named Chéron who counted among his protéges Chaïm Soutine, Tsuguharu Foujita and Kees van Dongen. Louis Metman gave him a small living allowance, which enabled him to go to paint in Toulon, sending back his paintings to Chéron.

The Great Depression of 1931 stopped these stays and obliged him to take a job in a workshop restoring paintings. He became the owner of the workshop a few years later. He continued to send his work to the Paris Salon and to exhibit in the Bernheim and Charpentier galleries.

It was through his work restoring paintings that he met Sacha Guitry and they became friends. Gard painted portraits of the actress Jeanne Fusier-Gir, of Sacha Guitry and of Sacha's ex-wife, the actress Lana Marconi.

1940s and 1950s

In 1946, Gard founded the art review Apollo (not to be confused with the English Apollo magazine), at first writing most of the articles and signing under his own name or a pseudonym. He started a crusade against abstract art and explained his own conception of art, whose only sensible criterion seemed to him to be to imitate nature.

This work as writer and art restorer slowed down his painting work and his exhibitions at the Castet gallery, but it did not stop them completely.

When Sacha Guitry died in 1957 he lost a friend, an admirer and a significant supporter.

1960s and 1970s

In 1960, the French State bought one of his paintings (Les roses rouges) ("Red Roses"). From that moment on, as soon as he could escape from his restoration workshop, he ran to take refuge in Les Bonhommes in the forests of L'Isle-Adam, Val-d'Oise, where he painted subjects as easy to conceive as they are hard to make: pond life, tricks of the light, the wind on leaves and sky, the changing seasons, etc.

Three years before his death, he gave the proceeds from his workshop to his son, and wrote to him: "I had hoped that in the life of art that I had, I would meet some true art lover: I gave up this idea because I found only speculators or people who wanted vane family portraits. I concluded that your artistic sense is better than that of all these fake collectors."

In his workshop on Rue Bourdonnais, where customers became increasingly rare, he continued to write all that he still had to say on art and life.

He painted only two more paintings, the last one (Le Géranium rouge), "The Red Géranium" a month before he died, on 12 November 1979, alone and destitute in his studio in the Quai des Grands-Augustins, where his final illness set in.

Paintings

Early career

Gard's relatively discreet originality passed almost unnoticed in the thrusting times for art that he lived in. He remained distant from 20th century movements laying claim as the heirs of the impressionists, be it Paul Cézanne or Vincent van Gogh, and his art was deep and authentically attached to the French painters of the 19th century who had been able to get through the midst of official red tape and reconcile pictorial art with truth, freshness, and nature. In enlisting the great historical or mythological works, Gard goaded the Impressionists: "the folly to think something can be achieved without thought, just by representing light and colour".

1920s and 1930s

Until 1926, when Fauvism, Cubism and Abstract styles came to the fore, Gard stayed away from theory and, it seems, followed Corot's lessons when he installed his easel on street corners in Morigny or Étampes and practiced with a palette of soft and refined tones.

From 1927, putting to use his stays in Toulon studying light and the harmonies of tone, he expressed himself in still life pictures of vigorous forms basked in a vibrant and colourful atmosphere, or in nudes with glowing flesh. He used knife-and-plaster for a vigorous and open touch, sometimes broad, sometimes tight, working with harmonies sometimes harsh, sometimes delicate. This painting style, which seen up close shows a rash and almost confused aspect, offers at a distance an extraordinary force and luminosity. Gard uses pure colour with a dexterity which belongs only to the great colourists, without ever going overboard. He ponders and solves one of the most complex problems of painting: shadows. He said: "For the part of a picture in shadow not to cause the death of a painting, by creating an inert zone, it must be luminous. A shadow must give the impression that it can move and not seem to be fixed to a spot: a shadow must express as much life as light."

Starting then, a very particular phenomenon of colour appears in his paintings: Aura. Strangely for a time when one saw so many extravagances, the colourful aura in which Gard bathed the subjects of his paintings received skepticism from the critics, who reproached him for what they thought was a pure fantasy; in particular the paintings with sharp contrasts (such as flowers). But it didn't matter: Gard, with his eye ready to seize the narrowest shafts of colour, really saw these auras — and this is the role of the great painter, to pay attention to a phenomenon that a less sensitive eye does not always see.

From 1932 Gard was definitively established in Paris, and although he had never seen Mediterranean light, he continued to explore this field in his still lives, his paintings of flowers and his portraits.

1940s to 1960s

The 1940s, when Gard met Sacha Guitry, are marked by several portraits of the famous: Sacha Guitry, Lucien Daudet, Count Doria, Baroness Hottinguer, Georges Renand, and many others.

In the 1950s Gard painted a series of still lives and flowers where he tried to fuse together two of his preoccupations in the same work, which, technically, are not easy to reconcile and from which he turns sometimes to one, sometimes to the other, the two tendencies fighting, one yielding to the other in turn: the love of a precise contour, the solidness of things, detail; and then the love of fireworks, of explosions of colour.

In the 1960s, he returned to the daily grind, no doubt more out of necessity than by choice. His friend Sudreau, the Secretary of State, gave him a room in the castle of Bonhommes in l'Isle-Adam forest. The castle grounds, with its diverse trees, its ponds and its changing aspects tracking the changing of the seasons, offered to Gard a multitude of subjects. Since he could only make short trips there for a day or two, he chose to make drafts. He tried to seize the effects of light, wind, fog, snow, rain, playing in the trees, the meadows, the water or the sky. The light is expressed in prominent fluid brushstrokes, which do not seek to flatter the layman's eye. For the expert, these landscapes are a collection of erudite and delicious harmonies which sing nature.

1970s

At the start of the 1970s, he returned to a series of still lives where he expresses the science of reflections in glass, as well as his science which consists in making one can feel how objects differ. He painted his last portraits. In the Jeune homme au manteau ("Young Man With Coat"), he pays homage to Titian, reaffirming, in the midst of the non-figurative art movement, his ties with the Enlightenement and Impressionist painters.

Writing

1930s and 1940s

Gard took notes and wrote comments on art since he was seventeen years old. He gave conferences in Paris in the 1930s. He confessed this was not his gift, so he soon gave it up and started the practice of introducing his exhibition catalogue with a lecture on painting, often a satire against certain movements, the Salons or the art critics.

In 1943 and 1944, he wrote five articles for the weekly magazine Panorama: "On Still-Life", "Forms and the plurality of exactness in painting", "Gauguin's Heritage", "Backbones won't swallow", "'Gérôme', or 'the blunder of an era'".

In 1946 he founded the bi-monthly Apollo, in which he published more than two hundred articles over ten years including "The 'Avanced' advance into the void", "We must discourage fine art", "The imitation of nature is the only desire in the plastic arts", "The 'golden number' is in nature", "Art has deserted France", "Rules on the harmony of colours and volumes", "The love of art is a bastion against the robot", "We must support art education", "Rules are necessary", "Against publicity", "Speculations on the fine arts", "Nature or nothing", "Refutation of Cubism", "The commercial genius", and so on. He set forth his position toward non-figurative art, explored its origins (which he considered fallacious), and highlighted the lack of understandable criteria by which to judge which works are valuable which are not.

1970s

He continued to write on similar topics for L'Amateur d'Art ("The art lover") and in the 1970s for the journal Rivarol.

Quotations

- For more than a century the error of painting has been to be cerebral instead of pictorial.

- Through history, we sometimes see outstanding geniuses. We give them no complications: genius is simple because it is all it needs to be.

- Fashion is the opposite of what one has just finished. The dislike of certain errors leads one sometimes to the opposite errors.

- In the arts, momentary practical success is never brought by the assurance of quality but by a tendency to it. One can only sail with the wind if one is in the wind.

- Masterpieces do badly in a democracy. It is best that a masterpiece has a shiny face, since the hordes don't look at the back side.

- Manet was not in fashion yesterday, and he wouldn't be today: too much daring for his time, not enough for ours. It is just a big picture.

- The genius of art is the genius of infinitesimal yet precise values.

- In art, it's the little nothings that make masterpieces. If Manet's white were less or more pink, it would not be Manet any more.