Kolobeng Mission

Kolobeng Mission (also known as the Livingstone Memorial), built in 1847, the third and final mission of David Livingstone, a missionary and explorer of Africa. Located in the country of Botswana, 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) west of Kumakwane and 25 kilometres (16 mi) west of Gaborone off the Thamaga-Kanye Road, the mission housed a church and a school and was also the home of David Livingstone, his wife Mary Livingstone, and their children. While here, Livingstone converted Sechele I, kgosi of the Bakwena and taught them irrigation methods using the nearby Kolobeng River. A drought began in 1848, and the Bakwena blamed the natural disaster on Livingstone's presence. In 1852, Boer farmers attacked the tribes in the area, including the Bakwena at Kolobeng in the Battle of Dimawe. This prompted the Livingstones to leave Kolobeng, and the mission was abandoned. A fence was installed around the site in 1935, and the mission is now preserved by the Department of National Museum and Monuments under Botswana's Ministry of Environment, Wildlife and Tourism.

| Kolobeng Mission | |

|---|---|

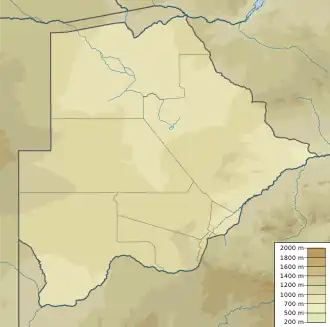

Location of Kolobeng Mission in Botswana | |

| Location | Kumakwane, Kweneng, Botswana |

| Coordinates | 24°39′17″S 25°39′56″E |

| Elevation | 1,030 metres (3,380 ft) |

| Built | 1847 |

| Built for | David Livingstone |

| Governing body | Department of National Museum and Monuments |

Indeed, not ten inches of water fell during these two years, and the Kolobeng ran dry; so many fish were killed that the hyaenas from the whole country round collected to the feast, and were unable to finish the putrid masses. A large old alligator, which had never been known to commit any depredations, was found left high and dry in the mud among the victims.

David Livingstone on the drought between 1848–1849

History

Before David Livingstone arrived in Kolobeng, he was first assigned to a London Missionary Society mission in Kuruman in present-day South Africa in 1841.[1] He met Sechele I, leader of the Bakwena, while stationed in Kuruman. He later moved to Chonuane with the Bakwena and stayed there for a year. A drought occurred, and Livingstone convinced Sechele that rainmaking would not end the drought, and that the only way to water their crops was to "select some good, never-failing river, make a canal, and irrigate the adjacent lands".[1] They chose the Kolobeng River 40 miles (64 km) away and immediately moved there.

At their new location, the Bakwena built a dam and canal from the river as well as a school while Livingstone built Sechele's house, taught the clan how to irrigate fields, and practised Western medicine. Livingstone stated that their attempt at living at Kolobeng "succeeded admirably".[1] However, after the first year, a drought caused the river to run dry. Livingstone reported that the temperature of the soil in the sun 3 inches (7.6 cm) below the surface at noon reached 134 °F (57 °C).[1] Livingstone's fourth child, Elizabeth, died two months after being born during the drought and was buried at Kolobeng.[2] During the drought, the Bakwena, seeing that other tribes in the area were receiving rain, asked Livingstone to produce rain, but, while he sympathized, he tried to stop their rainmaking rituals and requested that they focus more on praying to God. Sechele's uncle had this to say about Livingstone and his response:

We like you as well as if you had been born among us; you are the only white man we can become familiar with (thoaela); but we wish you to give up that everlasting preaching and praying; we can not become familiar with that at all. You see we never get rain, while those tribes who never pray as we do obtain abundance.[1]

In 1852, the Battle of Dimawe occurred. Boer farmers raided the settlement, stealing cattle, wagons, and women, but through the command of Sechele, the Bakwena successfully defended their settlement.[3] The raid and the ongoing drought caused unrest among the Bakwena so they left the settlement. Livingstone also left the mission for Cape Town to restock for his future travels further inland while his wife and children returned to England.

Present-day

The site sat unattended until 1935 when a doctor from the Scottish Livingstone Hospital in Molepolole built a fence around the mission. Today, only the remnants of the irrigation system and the foundations of the buildings remain.[4]

Legacy

In honour of the 200th anniversary of David Livingstone's birth, a play, I Knew A Man Called Livingstone, was created. The play is told through the eyes of the African people whom he met during his travels, and part of the play focuses on his time spent at Kolobeng.[5]

See also

References

- Livingstone, David (1857). "Missionary travels and researches in South Africa". Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- Heidenreich, Marion. "Kolobeng" (in German). Stadthagen, Germany: Nyala Tours. Archived from the original on 13 June 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- Legodimo, Chippa (22 June 2012). "How the Battle of Dimawe shaped Botswana". Arts & Culture. Mmegi. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- "Livingstone Memorial – Kolobeng Botswana, Livingstone Safari Botswana". Botswana Travel Guide. Archived from the original on 22 November 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- McVicar, Ewan. "I Knew A Man Called Livingstone: Education resource pack" (PDF). Toto Tales. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

External links

- Official government page on Kolobeng

- Other historical sites in Botswana

- Official page of I Knew A Man Called Livingstone

- Kolobeng Find a Grave page for the Livingstone cemetery at Kolobeng.

- Elizabeth Pyne Livingstone grave site Find a Grave memorial page for infant Elizabeth, which includes a photograph of the grave site.