Koffi Olomide

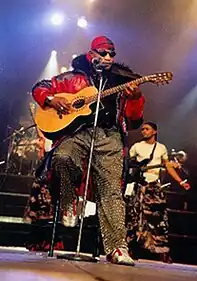

Antoine Christophe Agbepa Mumba (born July 13, 1956),[1] known professionally as Koffi Olomidé, is a Congolese soukous singer, dancer, producer, lyricist, composer, bandleader, and the founder of Quartier Latin International.[2][3] With numerous gold records, he is widely known for his flamboyant style and dynamic stage presence.[4][5]

Koffi Olomidé | |

|---|---|

Koffi Olomidé at Paris La Défense Arena, 2020 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Antoine Christophe Agbepa Mumba |

| Also known as |

|

| Born | 13 July 1956 Stanleyville, Belgian Congo (now Kisangani, Tshopo Province) |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instrument(s) | Vocals, guitars, percussion |

| Years active | 1977–present |

| Labels |

|

| Spouse(s) |

|

Emerging as a lyricist for various superstars within the Congolese music industry, he gained prominence in 1977 with the release of "Princesse ya Synza," a trio featuring Papa Wemba and King Kester Emeneya.[6][7] In 1986, he established and directed the Quartier Latin International, which accompanied him on stage and in producing his albums since 1992, serving as a launching pad for emerging music stars, including Fally Ipupa, Jipson Butukondolo, Deo Brondo, Montana Kamenga, Bouro Mpela, Ferré Gola, Marie-Paul Kambulu, Eldorado Claude, Djuna Fa Makengele, Soleil Wanga, Laudy Demingongo Plus-Plus, Éric Tutsi, and among others. His career experienced a resurgence in 1990 when he signed a record deal with SonoDisc.[8][9]

Revered as a legend in Congolese and African music, with a career spanning nearly five decades, he is the first African music artist to fill the Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy and one of the 12 African musicians listed in the 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die for his album Haut de Gamme.[10][11][12][13] Throughout his forty-year career, Agbepa has recorded 28 studio albums, including seven under the Latin Quarter banner, one in collaboration with Papa Wemba, and 18 live albums, amounting to an extensive repertoire of over 300 songs.[14][15][16]

He has won seven Kora Awards, including an illustrious quartet during the 2002 KORA Awards edition for his album Effrakata, encompassing the awards for Best Male Artist of Central Africa, Best Video of Africa, Best Arrangement of Africa, and the Jury Special Award.[16] In 2013, he launched his label, Koffi Central. He released 13ième apôtre on October 13, 2015, a quadruple album comprising forty songs, which he proclaimed to be his final album before later resurfaced with Nyataquance and Légende Édition Diamond.[17][18][19][20]

Early life and career

Childhood

Antoine Christophe Agbepa Mumba was born on July 13, 1956, in Stanleyville (present-day Kisangani), in the Belgian Congo (now Democratic Republic of the Congo), to Aminata Angélique Muyonge and Charles Agbepa.[21][2][22] His mother named him Koffi in homage to his Friday birth. He grew up in Kinshasa's Lemba commune until his family relocated to Lingwala in 1973.[22][23][24] In his youth, he hoped to become a professional footballer but later pivoted towards a career in music, inspired by old-school Congolese rumba luminaries such as Franco Luambo, Le Grand Kallé, Vicky Longomba, and Tabu Ley Rochereau.[2][18][25] At 13, he began playing the six-string guitar mentored by Papa Wemba.[22][26]

At the cusp of adulthood, at 18, he earned a scientific baccalaureate in high school and went on to study business in southwestern France at the prestigious University of Bordeaux, supported by his father.[2][20][27] During the mid-1970s, Agbepa returned to Kinshasa during school breaks and became a lyricist for artists from the Zairian scene, earning him the sobriquet of the "most famous student in Zaire" and seizing the attention of Papa Wemba, who had recently departed from Zaïko Langa Langa and was actively engaged as a lyricist.[22]

1977–1983: Music debut

Emboldened by his elder brother in Kinshasa, Agbepa ventured into the recording studio, crafting his compositions like "Onia," later featured as "Tsiane" within the Pas de faux pas album in the 1990s.[17][22] With the establishment of Viva La Musica by Papa Wemba, he contributed songs such as "Mère supérieure," "Ebalé mbongé," and "Aissa Na Zoé".[17][28][29][30][31] In 1977, alongside Wemba and King Kester Emeneya, he composed "Asso" and "Princesse ya Synza," which garnered him the "Best Singer-Songwriter" in Zaire.[32][17][2] In subsequent years, he released songs like "Samba Samba," "Ekoti ya Nzube," "Elengi ya Mbonda," and "Bien Aimée Aniba," with the latter clinching him the "Best Star of Zairian song."[17] As he made music during off-peak hours and principally during the holidays, straddling Zaire and France, he obtained a Bachelor's degree in Business economics In 1980 with his thesis "La commercialisation des richesses minérales du Zaïre"[10][22][18]

1983–1984: From Ngounda to Elle et moi

Returning to Zaire, Agbepa's stature was solidified through his collaboration with Papa Wemba, which laid the spadework for the release of his debut solo album, Ngounda, in 1983.[33] Recorded in Brussels, under Roland Leclerc's stewardship, it featured Josky Kiambukuta of Franco Luambo's TPOK Jazz. He fondly described this endeavor as his "first genuine experience in a professional studio." While the album's reception was a blend of acclaim and critique, he continued his upward trajectory, culminating in his subsequent release, Lady Bo, which featured King Kester Emeneya.[34]

1985–1986: Diva, Ngobila and Quartier Latin International

In 1985, he released Diva. Orchestrated by Zaïko Langa Langa, the album struck a chord and marked the beginning of his meteoric rise within the music industry.[35] While his initial lyrical themes found resonance predominantly among young women, his distinctive "Tcha Tcho" (also known as Soukous Love) style of music transgressed such boundaries, capturing the hearts of audiences across diverse demographics.[34]

In 1986, he released Ngobila, which didn't garner considerable success. The album's titular track narrates the poignant tale of a man standing on a port quay, witnessing the departure of his beloved, uncertain if fate would reunite them. Later that year, he formed the Quartier Latin International.[36][18][2]

1987–1989: Rue D'Amour, Henriquet and Elle et Moi

At the start of 1987, rumors disseminated that Agbepa had succumbed to AIDS in Europe.[25][37] This episode of sagas enormously affected Agbepa, rousing him to compose the song "Ngulupa," in which he responds to his critics with the lyrics: "Bomoni té, boyoki yango, tika kotuba koloba, tuba tuba eza mabé" (You haven't seen anything, only heard; stop talking about things you don't know; verbal diarrhea is a bad thing).[25][37] He also addresses illness in "Dieu Voit Tout," singing: "Kuna na mboka lola ata bato oyo ya sida, bazuaka pe kimia oyo ya seko" (At least in heaven, there is eternal peace even for those who suffer from AIDS).[25][37]

In mid-1987, he released Rue D'Amour, later reissued on CD in 1992 by Sonodisc under the Golden Star dans Stéphie album.[25][17] The album features six partially unreleased tracks and showcases Agbepa singing for VIPs for the first time. Among its tracks, he composes "Mosika na Miso" (Far from the Eyes) for Claudien Likulia, the son of General Norbert Likulia Bolongo, and pays tribute in "Myriam Moleka" to Myriam, a late wealthy heiress of the Moleka family. In recognition, a house was constructed for Agbepa in Kinshasa's Bandalungwa commune.[25][17] Other tracks on the album delve into themes of love in the title track "Stéphie," as well as covetousness towards him in "Petit frères ya Yesus" and "Droits de l’homme."[37]

During the summer of 1988, he released the Henriquet album, an eponymous homage to Miss Zaire of that year.[25] It garnered resounding success, propelling Agbepa into the vanguard of the musical milieu across Zaire, the Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Uganda, Zambia, Tanzania, Burundi, and Rwanda. Eminent figures, including Lukunku Sampu of Zairean television, extolled him as "the biggest current star of Zairian music." Comprising a symphony of six tracks, it featured Manu Lima.[17][18]

In August 1989, he released the album Elle et Moi. The track "Elle et Moi" is dedicated to his daughter Minou.[17][18] This opus resonates with Agbepa's guitar and bass performances and is orchestrated by Manu Lima. The distinct cadence of Tcha Tcho undergoes a contemporary transformation, featuring a modern sonic palette and a more assertive embodiment of the animating spirit inherent to Congolese music.[17][18] While in Paris, rumors surfaced of his alleged arrest with drugs but were swiftly quelled by Laudert, a confidant of the singer, via television broadcast.[17][18]

1990–1994: Les prisonniers dorment, Haut De Gamme, Pas de faux pas, Noblesse oblige, and Magie

In 1990, Agbepa released the album Les prisoners dorment under his new record label, Sonodisc, selling over 100,000 copies.[38] Gilles Obringer acclaimed the album on his show "Canal Tropical" on Radio France Internationale (RFI). His distinctive Tcha-Tcho style reached its peak in the 1990s, and he earned his first gold record in 1994 for the album Noblesse Oblige. In 1991, he garnered significant awards at the Trophées de la musique Zaïroise, including the 'Best Songwriter' and the 'Best Album of The Year'.[38][18]

In February 1992, he released Haut De Gamme, the only Congolese album featured in the 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[10] On June 1, 1992, he released Pas de faux pas, embarking on a continent-wide tour and receiving invitations to perform at the presidential palace of Gabon by President Omar Bongo Ondimba, as well as during the Congolese presidential campaign by President Denis Sassou-Nguesso.[38] That same year, he and Jossart N’Yoka Longo were ensnared by the legal apparatus following the summons by the Prosecutor General of Kinshasa, stemming from perceived lascivious animations within their musical compositions but were later released.[38][17]

On August 14, 1993, he performed at Paris Expo Porte de Versailles. In September 1993, Agbepa released the album Noblesse Oblige, which sold over 100,000 copies and attained gold status. That same year, he toured Kenya and performed at Safari Park Hotel.[18][17][39][40] On November 22, 1994, amid the Rwandan genocide, he launched the album Magie, accompanied by music videos shot in the United States and Paris.[18] He celebrated triumphs in Paris, including a successful show at the Paris Expo Porte de Versailles and a performance at FNAC Forum. At the African Music Awards in December 1994, held at the Palais des Congrès at the Hotel Ivoire, he earned accolades for 'Best Male Singer' and 'Best Video Clip' in Ivory Coast.[18]

1995–1999: V12, Wake Up, Ultimatum, Loi, Droit de Veto, and Attentat

His album V12, released on October 9, 1995, earned him his second gold record, with sales overextending 100,000 copies. The track "Fouta Djallon" ranks among the top 20 Congolese rumba songs. In December, he presented the album during a concert performance at Ivoire InterContinental in Abidjan.[41][38][17]

In 1996, he released the album Wake Up, featuring Papa Wemba, to quash rumors of vendetta with Papa Wemba.[42][43][17] On May 21, 1997, he unveiled Ultimatum, the band's 3rd album, followed by the release of Loi in the same year. The "Loi" track is emblematic and became the hallmark of Ndombolo, a dance that vacuumed across Africa from the late 1990s to the 2000s.[38][44][45] The album achieved gold status with sales surpassing 100,000 copies. In 1997, at the initiative of producer Ngoyarto, Agbepa released his first compilation "N'Djoli," bringing together his initial songs with the participation of Papa Wemba, King Kester Emeneya, and Félix Manuaku Waku.[38]

On December 31, 1998, he released Droit de Veto, with stage productions on August 29 at the Olympia Hall (where nearly 2,000 people were turned away), November 7 at the Zénith de Paris (where Quartier Latin engaged in a dance-off with the Haitians of Tabou Combo, luring a crowd of 7,000), and subsequently at the Brixton Academy for the first time. Just a week after his sold-out concert at the Paris Olympia, he secured the title of Best Central African Artist at the Kora Awards.[46][47][18][48]

In November 1999, Agbepa released Attentat, an album titled in homage to the 1998 attacks on American embassies in Africa. The album achieved gold status within 2 months, selling over 100,000 copies. Recorded across Paris and South Africa, it stands as a significant achievement across Africa.[49][50]

The 2000s

Breaking records on February 19, 2000, Agbepa became the first African artist to perform at and fill France's largest hall, the Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy, with 17,000 attendees solely through word-of-mouth promotion.[51][52] The concert, which followed previous sold-out performances at venues like Paris Expo Porte de Versailles, Olympia, and Zénith de Paris, was documented by journalists from France 2, Métropole Television, Canal Plus, and Ma Chaîne Musicale.[17][52][53][54]

On December 26, 2000, Agbepa released the band's 5th album, Force de Frappe, featuring songs from various artists. The album swiftly secured a prominent position on music charts of major radio and TV channels, followed by a tour in West Africa, Nairobi, Mombasa, and Paris, where he performed at Zénith de Paris on July 14, 2001.[55][56][57][58]

Agbepa began recording his album Effrakata in Paris and Charlotte.[55] Before its official release, he delivered a concert at the Lincoln Center Festival in New York City on July 16 as part of a major American tour.[59] On December 7, 2001, he officially released Effrakata, a double album comprising 16 tracks, which became ubiquitous, meriting him a gold record with sales eclipsing 180,000 copies.[60][17] Several shows were credited to him, collectively known as the "Western tours."[61] The first leg commenced on September 2 in Geneva and concluded in January 2003 in Paris, with concerts and showcases held in cities such as London and Brussels.[61] The album won him four KORA Awards on November 2, 2002, in South Africa for Best Male Artist of Central Africa, Best Video of Africa, Best Arrangement of Africa, as well as the Jury Special Award, earning him the epithet "Quadra Koraman."[62][63] On November 16, he presented his trophies to Kinshasa's governor, Marthe Ngalula Wafuana, Minister of Culture and the Arts, and President of the Republic, Joseph Kabila.[63] Agbepa and Quartier Latin later won seven awards, including Best Album of the Year, Best Presenter for Kérozène, Best Author/Composer, Best Artist-Musician for Koffi Olomidé, Best Singer for Fally Ipupa, Best Orchestra for Quartier Latin, and the prestigious Best Song of the Year for their track "Effervescent."[17]

On March 7, 2003, he released the band's 6th album, Affaire d'Etat, housing compositions like Fally Ipupa's Ko-Ko-Ko-Ko, Fofo le Collégien's Inch'Allah, and Bouro Mpela's "Calvaire," among others. Produced by David Monsoh, the song "Inch'Allah" won the KORA Award for Best African Group, shared with Ivorian ensemble Anti Palu.[64][65] On April 12, 2003, he performed at the Zénith de Paris with his Quartier Latin International.[66] On May 3, 2003, a tragedy occurred at the Stade de l'Amitié in Cotonou, resulting in the death of 16 people due to a stampede caused by the influx of attendees.[67]

Initially slated for December 2003, the album Monde Arabe was released on December 7, 2004. In the wake of Sonodisc's closure, he self-produced the 18-track double album, distributed by Sonima.[68] On April 16, 2005, he performed at the Royal Festival Hall in London.[69] On December 4, 2005, he won the 10th edition of the KORA Awards, receiving the Lifetime Achievement Award in South Africa. The organizers offered a prize of $100,000 for the award recipient.[17] The following year, his magnum opus, Magie, was reissued by producer Suave, extending the collection to encompass the best tracks from Agbepa's career. Each CD contained a 2-page booklet, which left numerous fans disgruntled with the Suave label.[17]

On October 13, 2006, Agbepa released his band's 7th album, Danger de Mort, which became the band's last album due to consecutive departures of some musicians.[70][71][72] On October 13, 2007, he performed at the Zénith de Paris with his reinvigorated group, Les Mineurs du Quartier Latin.[73][74][75]

On August 7, 2008, he released the album Bord Ezanga Kombo, a 17-track double album featuring prominent African music stars such as Youssou Madjiguène Ndour on the song "Festival" and Lokua Kanza on "Diabolos."[76] Within four months, the album sold 60,000 copies, achieving gold record.[77] The album faced censorship by the DRC's censorship commission in January 2009 but was de-censored on February 23, 2009.[78] That same year, he released "La Chicotte à Papa," a 7-track maxi-single.[79]

2010–2015: Abracadabra and 13ème Apôtre

In early December 2011, Agbepa's album Abracadabra was pirated three weeks before its planned release on December 23, 2011.[80] He directly accused Les Combattants, a group of demonstrators against artists supporting the former president of the DRC, Joseph Kabila, of being behind the piracy. He alleged that they aimed to tarnish his musical career by disseminating all the songs across the internet.[81][82] His producer ultimately decided to release the album on January 10, 2012, as a countermeasure against piracy. Agbepa also distributed his new album for free in Kinshasa.[83][84] However, he faced accusations of impropriety due to certain lyrics in the track "Jeune Pato."[84]

In May 2013, he began recording his new album 13ème Apôtre, announcing that it would be the 20th and final album of unreleased songs in his career.[85][86] In mid-2014, Agbepa commenced filming music videos for select tracks and invited collaborators to partake in the album.[87][88] In July, controversy arose over the involvement of Ferré Gola and Fally Ipupa—both prominent rivals from the 5th generation of Congolese music—in Agbepa's latest album.[89][90]

Amid quarrels with artist JB Mpiana, who branded him "Old Ebola" to denigrate him, Agbepa ingeniously reclaimed the slur, incorporating it into banners heralding his forthcoming productions commencing from November 2, 2014.[91] On October 21, 2014, Agbepa was arrested by Kinshasa police.[92] Colonel Pierrot Mwana-Mputu, the director of information and communication for the police, expressed that Agbepa's use of "Old Ebola" was immoral and went against the international community's efforts to combat the hemorrhagic fever.[92] He stated,

"He presented himself as (Old) Ebola while we are battling this epidemic. This conveys an immoral message and goes against the efforts of the international community to combat hemorrhagic fever."[92][93]

On July 26, 2015, during the show "Karibu Variétés" on Radio-Télévision Nationale Congolaise (RTNC), Agbepa announced his latest album of unpublished songs, 13ème Apôtre.[94] The album consisted of 39 unreleased tracks spread over four CDs and was officially released on October 13, 2015. It became an instant hit, selling over 22,000 copies in one day and 46,000 copies in a mere week. The album rapidly topped the charts, ranking number 1 in the iTunes Store World Music category and 15th in the iTunes World ranking.[95] The song "Selfie" (alternatively known as "Ekoti té") became a viral sensation with over a million views on YouTube in just three weeks.[96][97] The hashtag #OpérationSelfie gained traction across various social media platforms and was embraced by renowned personalities like French singer vocalist Matt Pokora, Ivorian football player Didier Drogba, and French-Congolese football player Blaise Matuidi.[98][97][96] In recognition of his triumphs, Trace Africa dedicated the month of October to Agbepa.[99] Several programs were aired, retracing his journey, and a 25-minute documentary that offer insights into his daily life and career. The French channels TV5Monde and France 24, along with other media worldwide from Canada, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Senegal, the United Kingdom, and the United States, also extensively covered the "Selfie" phenomenon.[99]

His music

Olomide's album Haut de Gamme: Koweït, Rive Gauche is listed in 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[11] In March 2003 Olomide released "Affaire D'Etat", a double CD album featuring 18 tracks. Most of his songs have the same tunes, but slightly different lyrics.

Olomide was part of the Papa Wemba musical, in the early 1980s. He has trained many young musicians, some of whom have since left his Quartier Latin band and gone solo. Some of those who have left are Fele Mudogo, Sam Tshintu, Suzuki 4x4, Soleil Wanga, Bouro Mpela, Fally Ipupa, Montana Kamenga, Ferre Gola. However, Suzuki 4x4 has recently showed up once more in some of Quartier Latin shows, along with new recruits like Cindy Le Coeur, a female singer with very high pitched vocals, recorded in the song L'Amour N'existe Pas (Love doesn't exist).

Agbepa—who mostly refers to himself as "Mopao"—has a new release known as La Chicotte a Papa, having recently excelled in hits like Lovemycine, Diabolos, Grand Pretre Mere and Soupou, Cle Boa, among others. Koffi's talent could be compared to the once king of African rhumba, Franco Luambo Makiadi, who also saw many artists pass through his expert hands during his days. Today, Olomde is one of Africa's most popular musicians.[100]

Allegations

In 2012, Agbepa allegedly assaulted one of his producer for abuse and no respect of contract and received a suspended three-month sentence.[101]

In July 2016, while on a concert trip to Kenya,[102] Olomide was filmed making a kicking move towards one of his dancers. The action was widely condemned and caused the suspension of the concert as the video went viral. On his return to his home country, he was arrested five days later at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, allegedly for the same unpunished action. He was subsequently jailed for 4 days without judgement and released with no explanation. However, it was later revealed that the former Congolese president's wife, Mrs Olive Lembe di Sita, was behind the arrest because of her association for women's protection against violence and rape.[5]

In, 2018 he was ordered for arrest of a photographer in Zambia,[103] he left the country before arrest.

In 2019, He was found guilty by a French court of statutory rape of one of his former dancers when she was 15 years old.[103] He was handed a two-year suspended jail sentence in absentia, as he did not attend court in France.

Legacy

Koffi Olomide is among the greatest Congolese and African musical artists of all time. Many artists look up to him for inspiration. President Felix Tshisekedi of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) recently appointed him as one of the country's cultural ambassadors.

Discography

Studio albums

- Ngounda (1983, Tchika)

- Lady Bo (1984, Goal Productions)

- Celya-Ba (1985, Struggling-Man Productions)

- Ngobila (1986, Afro Rythmes)

- Diva (1986, Espera)

- Dieu Voit Tout (1987, self-released)

- Rue D'Amour (1987, O'Neill)

- Henriquet (1988, Kaluila)

- Elle Et Moi (1989, Kaluila)

- Les Prisionniers Dorment... (1990, Sonodisc)

- Haut De Gamme ''Tcha-Tcho, Echelon Ngomba'': Koweït, Rive Gauche (1992, Tamaris)

- Pas De Faux Pas (1992, Quartier Latin album, Tamaris; Sonodisc)

- Noblesse Oblige (1993, Sonodisc)

- Magie (1994, Quartier Latin album, Sonodisc)

- V12 (1995, Sonodisc)

- Ultimatum (1997, Quartier Latin, Sonodisc)

- Loi (1997, Sonodisc)

- Droit De Véto (1998, Quartier Latin album, Sonodisc)

- Attentat (1999, Sonodisc)

- Force De Frappe (2000, Quartier Latin album, Sonodisc)

- Effrakata (2001, Sonodisc)

- Affaire D'État (2003, Quartier Latin album, Sonodisc)

- Monde Arabe (2004, Sonima)

- Danger De Mort (2006, Quartier Latin album, Sonima)

- Koffi (also called L'album sans nom or Bord Ezanga Kombo) (2008, Diego Music)

- Abracadabra (2012, Rue Stendhal)

- Bana Zebola (2015, Koffi Central)

- 13ième Apôtre (2015, Koffi Central)

- Nyataquance (2017, Koffi Central)

- Légende Ed. Diamond (2022, Koffi Central)[104]

Collaborating albums

- 8è Anniversaire (with Papa Wemba, Viva la Musica) (1983, Gillette D'Or)

- Aï Aï Aï La Bombe Éclate (with Rigo Star) (1987, Mayala)

- Glamour (with Duc Hérode) (1993, Air B. Mas Productions)

- Wake Up (with Papa Wemba) (1996, Sonodisc)

- Sans Rature (with Didier Milla, Madilu System, Papa Wemba) (2005, Sun Records)

See also

References

- Dan B. Atuhaire (21 April 2014). "10 Things You Didn't Know About Koffi Olomide!". Kampala: Bigeye.ug. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- Dictionnaire des immortels de la musique congolaise moderne (in French). San Francisco, California: Academia. June 2012. pp. 22–25. ISBN 9782296492837.

- Ellingham, Mark; Trillo, Richard; Broughton, Simon, eds. (1999). World Music: Africa, Europe and the Middle East, Volume 1. London, England: Rough Guides. p. 470. ISBN 9781858286358.

- "Koffi enchants Namibia". Truth, for its own sake. Retrieved 2023-07-07.

- Grand Lac Magazine/About 2016

- "Papa Wemba and Viva La Musica - playing with politics". www.nostalgieyamboka.org. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- Nlandu-Tsasa, Jean-Cornélis; Kindulu, Joseph-Roger M. (May 2009). Les cadres congolais de la 3è république (in French). Paris, France: Éditions L'Harmattan. p. 13. ISBN 9782296225190.

- "Koffi Olomidé". Congolese Music. 2020-12-10. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- Dictionnaire des immortels de la musique congolaise moderne (in French). San Francisco, California, United States: Academia. June 2012. pp. 22–24. ISBN 9782296492837.

- Koloko, Leonard (April 25, 2012). Zambian Music Legends. Morrisville, North Carolina, United States: Lulu.com. pp. 202–203. ISBN 978-1-4709-5335-5.

- Parker, Steve (2005). "1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die". London: Rocklistmusic.co.uk. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- Trapido, Joe (December 2016). Breaking Rocks: Music, Ideology and Economic Collapse, from Paris to Kinshasa. New York City, New York State, United States: Berghahn Books. p. 84. ISBN 9781785333996.

- Shepherd, John, ed. (2003). Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World: Africa and the Middle East. London, New York City: Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 30.

- Anadobi, Amanda (November 23, 2022). "Koffi Olomidé". BeeTeeLife. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- "Koffi Olomide". LA Entertainment. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- "Koffi Olomidé". Congolese Music. 2020-12-10. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- "Biographie Koffi Olomidé". musicMe (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- "Koffi Olomidé - Biographie, discographie et fiche artiste". RFI Musique (in French). September 2020. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- "Musique : Koffi Olomidé revient avec son nouvel album « Nyataquance » – Jeune Afrique". JeuneAfrique.com (in French). 2017-03-14. Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- Siar, Claudy (March 27, 2023). "Koffi Olomidé fait sa Libre Antenne #GénérationConsciente". RFI Musique (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-16.

- Kisangani, Emizet F. (November 18, 2016). Historical Dictionary of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Lanham, Maryland, United States: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 55. ISBN 9781442273160.

- "Personnes | Africultures : Olomide Koffi". Africultures (in French). Paris, France. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- "Koffi Olomide - African Music To Dance The Night Away". African Music Safari. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- Mombong, Jean-Claude (July 18, 2023). "Koffi Olomidé : un grand artiste aux deux visages". Laprosperite (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- "Qui est OLOMIDE Koffi - Abidjan.net Qui est Qui ?". business.abidjan.net (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- "Biographie de Christophe Agbepa Mumba, Koffi Olomidé". Kin kiesse (in French). December 10, 2021. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- Krisbios-Kauta, Adjuvant (August 28, 2022). "Ce que l'on sait sur les debuts artistiques de Koffi Olomidé". Kribios Universal (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- Olomide, Koffi (April 27, 2016). "Koffi Olomidé: «La mort de Papa Wemba, un grand handicap pour la musique africaine»". JeuneAfrique.com (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- Mavungu, Serge (2021-09-13). "Côte d'Ivoire : l'artiste Koffi Olomide humilié par le public à la 13è Édition du FEMUA!". Opinion Info (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- Nsapu, Dido (November 23, 2019). "Koffi Olomide dans «Un dollar», un registre que raffolent des Congolais". www.digitalcongo.net (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- "Papa Wemba and Viva La Musica - playing with politics". www.nostalgieyamboka.org. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- "Comment Koffi Olomide est devenu le roi de la rumba congolaise?". Griotys TV (in French). 2022-09-06. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- PAA (2002). "Koffi Olomide Biography". Pan African Allstars (PAA). Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- Kribios-Kauta, Adjuvant (Sep 23, 2022). "De Ngounda à Elle et Moi,... Retour sur les années 1980 de Koffi Olomidé". Kribios Universal (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- Anadobi, Amanda (November 23, 2022). "Koffi Olomidé". BeeTeeLife. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- "Vie personnelle, homme controversé, star des stars tout savoir sur Koffi Olomidé". togoweb.net (in French). May 17, 2021. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- Ngouegni, Rosine (July 15, 2020). "Trajectoire : Koffi Olomide, parcours, discographie du quadra koraman". kpjevents.com (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- Kribios-Kauta, Adjuvant (Apr 16, 2022). "13 albums paraphés par des trophées majeurs et des concerts historiques: la décennie 90 de Koffi Olomidé". Kribios Universal (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- "Top 5 des artistes congolais ayant obtenu un disque d'or" [Top 5 Congolese artists who have obtained a gold record]. Mbote (in French). April 27, 2018. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- "Kenya: Olomide's Big Date With Kenyan Fans". Allafrica. February 12, 2016. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- "V12 By Koffi Olomide, A Release You Definitely Should (Re)Discover!". Congolese Music. 2018-05-12. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- "Le Wenge des origines". www.adiac-congo.com (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- "La mondialisation musicale". reglo.org (in French). November 23, 2015. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- "Musique : 5 classiques de Ndombolo". Je Wanda (in French). 2016-01-14. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- "Les 7 Ndombolo qui nous ont fait vibrer aux années 90 à la veille de l'an 2000". Kribios Universal (in French). November 12, 2020. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- Bensignor, Francois (1998-09-01). "Koffi Olomidé à l'Olympia". RFI Musique (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- Koffi Olomide & Quartier Latin - Concert à l’Olympia de Paris (1998), retrieved 2023-08-18

- Kribios-Kauta, Adjuvant (September 7, 2021). "Koffi Olomidé et ses 5 Zénith de Paris". Kribios Universal (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- Lescure, Bernard (October 24, 2001). "Koffi Olomidé: «Je chante pour la femme»". archive.wikiwix.com. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Koffi Bercy 2000 - Partie 4 - Attentat Disque D'or (Gold Record), retrieved 2023-08-19

- René-Worms, Pierre (February 20, 2000). "Koffi Olomidé à Bercy". archive.wikiwix.com. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Daoudi, Bouziane (February 19, 2000). "Interview: Koffi remplit Bercy. La star zaïroise tient son pari grâce au bouche à oreille. Koffi Olomidé, en concert samedi à 23h à Bercy, Paris XIIe CD double: «Attentat» (Sono/Musisoft)" [Interview: Koffi fills Bercy. The Zairian star holds his bet thanks to word of mouth. Koffi Olomidé, in concert Saturday at 11 p.m. in Bercy, Paris XII double CD: "Attack" (Sono / Musisoft).]. Libération (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Labesse, Patrick (December 31, 2001). "Papa Wemba's Show: The Congolese singer in France for a special New Year's Eve concert". www1.rfi.fr. Translated by Julie Street. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- "Koffi Olomidé, the Great MOPAO, in concert at Paris La Défense Arena". Paris La Défense. November 27, 2021. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Kanka, Joseph (July 20, 2001). "Congo-Kinshasa: Koffi Olomide aux USA : Première production le 28 juillet en Caroline du Nord" [Congo-Kinshasa: Koffi Olomide in the USA: First production on July 28 in North Carolina]. AllAfrica (in French). Retrieved 2023-10-10.

- "Congo-Kinshasa: Koffi Olomide et Quartier Latin au Zénith" [Congo-Kinshasa: Koffi Olomide and Latin Quarter at the Zénith]. AllAfrica (in French). July 13, 2001. Retrieved 2023-10-10.

- "Koffi Olomidé - Congo Kinshasa (RDC) | cd mp3 concert biographie news | Afrisson". archive.wikiwix.com. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- "Koffi Olomide brings his Quartier Latin to Paris (2001)". Radio.Video.Music. 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- "Sénégal: Festivals d'été: L'Afrique en fête à New York" [Senegal: Summer Festivals: Africa Celebrates in New York]. AllAfrica (in French). July 27, 2001. Retrieved 2023-10-10.

- "Koffi Olomidé". Congolese Music. 2020-12-10. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Kanka, Joseph (October 18, 2002). "Congo-Kinshasa: Le triple Olympia confirmé pour janvier 2003" [Congo-Kinshasa: The triple Olympia confirmed for January 2003]. AllAfrica (in French). Retrieved 2023-10-10.

- Kanka, Joseph (November 5, 2002). "Afrique: Kora 2002 en Afrique du Sud: Koffi Olomide et les Makoma font honneur à la RDC" [Africa: Kora 2002 in South Africa: Koffi Olomide and the Makoma honor the DRC]. AllAfrica (in French). Retrieved 2023-10-10.

- Kanka, Joseph (November 22, 2002). "Congo-Kinshasa: Koffi Olomide présente ses quatre trophées aux kinois ce soir au GHK" [Congo-Kinshasa: Koffi Olomide presents his four trophies to the people of Kinshasa this evening at the GHK]. AllAfrica (in French). Retrieved 2023-10-10.

- Atchourou, Romaric (2003-04-29). "Koffi Olomidé, affaire de show !". Afrik (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Koffi Olomide & Quartier Latin reçoivent le Kora Awards (2003), retrieved 2023-08-19

- "Koffi Olomide de nouveau au Zénith le 12 avril 2003" [Koffi Olomide again at the Zenith on April 12, 2003]. archive.wikiwix.com. Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo. March 7, 2003. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Bornstein, David (May 6, 2003). "Bénin: le concert tourne à la tragédie". Libération.fr (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- René-Worms, Pierre (January 14, 2005). "Koffi Olomidé". RFI Musique (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Walters, John L. (2005-04-02). "Koffi Olomide". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ""Droit chnemin" de Fally Ipupa mieux que "Danger de mort" de Koffi Olomide!". archive.wikiwix.com (in French). 2006-11-07. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Nkutu, Jean-Pierre (September 8, 2006). "Congo-Kinshasa: Contradiction avec Koffi - Fally Ipupa - «Je suis toujours dans Quartier Latin»" [Congo-Kinshasa: Contradiction with Koffi - Fally Ipupa - “I am still in Quartier Latin”]. AllAfrica (in French). Retrieved 2023-10-12.

- Nkutu, Jean-Pierre (September 15, 2006). "Congo-Kinshasa: Après un long passage à vide - Babia grand bénéficiaire des " vides "" [Congo-Kinshasa: After a long slump - Babia big beneficiary of the “empties”]. AllAfrica (in French). Retrieved 2023-10-12.

- Koffi Olomide Zenith de paris, retrieved 2023-08-19

- Basango (October 21, 2007). "Koffi Olomide et les mineurs au Zenith de paris(13 octobre 2007)". Skyrock (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- "Koffi présente Cindy le Cœur au Zénith de Paris (Live), Koffi Olomidé". Qobuz. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Ferloo (2008-10-01). ""Diouma Diakhaté est fière de la chanson que lui a dédiée Koffi Olomidé", dit une de ses proches". Seneweb.com (in French). Dakar, Senegal. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Tsana, Sheila Elphie. "Un disque d'Or décerné à l'album sans nom de Koffi Olomide". Premier portail consacré à l'actualité politique, économique, culturelle et sportive du Congo et de la RDC (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Le "ss", Renaud (2009-02-20). "renaud-news l'actu afro-caraïbéenne: Acquitté par la censure, Koffi Olomide se relance dans la promotion !!!". renaud-news l'actu afro-caraïbéenne. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Atalaku (2009-12-27). "koffi olomide la chicotte à papaatalaku skyrock 2009 south africa w..." Skyrock (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Kianimi, Patrick (December 19, 2011). "La Conscience: L'album Abracadabra de Koffi Olomidé piraté" [La Conscience: Koffi Olomidé's album Abracadabra hacked]. archive.wikiwix.com (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- "KongoTimes: Abracadabra ou violeur de mineurs !" [KongoTimes: Abracadabra or rapist of minors!]. archive.wikiwix.com (in French). December 26, 2011. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- "RDC : qui sont les "combattants" qui attaquent les personnalités congolaises en visite à Paris ?". France 24 (in French). 2023-04-06. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Ambangito, Franck (2012-01-08). "Africahit - Koffi Olomide, en pleine promotion de son nouvel album « Abracadabra »". archive.wikiwix.com (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Kribios-Kauta, Adjuvant (June 4, 2022). "45 ans de carrière musicale, parlons des dernières cartouches de Koffi Olomidé (2010-2022)". Kribios Universal (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Diala, Jordache (July 30, 2013). "Africahit - Koffi Olomidé : démarrage des travaux de l'album « 13ème Apôtre»". archive.wikiwix.com (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- "Musique/Koffi Olomidé: «je ne ferai plus d'album»". news.abidjan.net (in French). March 17, 2014. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Ipan, B. (May 18, 2014). "Koffi Olomide : l'heure est au tournage et au montage des clips des chansons du dernier album de sa carrière". archive.wikiwix.com (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Kianimi, Patrick (July 14, 2014). "Album "13e apôtre": Koffi Olomidé se dit ouvert aux featuring". archive.wikiwix.com (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- "Koffi Olomide s'explique pourquoi Fally Ipupa n'est pas sur son album 13ème Apotre". MichaelBradok.com (in French). 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- "Koffi Olomide sur la participation de Fally dans 13ème Apotre: Fally Ipupa a déclaré «Place oyo Ferre Gola ayembi na koyemba Te! Po nakoya Kofula Ye»". The Voice of Congo (in French). July 18, 2014. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Assogba, Didier (2014-10-02). "Guerre entre JB Mpiana et Koffi Olomide surnommé "Vieux Ebola"". Wikiwix Archive (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Duhem, Vincent (October 22, 2014). "RDC: «Vieux Ebola», le nouveau surnom de Koffi Olomidé ne passe pas". JeuneAfrique.com (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- "Ebola: Le chanteur Koffi Olomidé arrêté en RDC". Libération (in French). October 21, 2014. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Kibangula, Tresor (October 14, 2015). "RDC : quand Koffi Olomidé s'autoproclame « 13e apôtre » – Jeune Afrique". JeuneAfrique.com (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Kibangula, Tresor (January 29, 2014). "RDC : Koffi Olomidé, une vie après la scène – Jeune Afrique". JeuneAfrique.com (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- "Musique: Koffi Olomidé séduit la planète selfie". archive.wikiwix.com. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Forson, Viviane (2015-11-05). "Musique: Koffi Olomidé séduit la planète selfie". Le Point (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Mesnager, Paul (November 2, 2015). "Vidéo : Didier Drogba et l'Impact de Montréal en mode « Selfie » de Koffi Olomidé – Jeune Afrique". JeuneAfrique.com (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- Balde, Asssanatou (2015-10-20). ""Koffi Olomidé, le 13ème apôtre" : Trace Africa célèbre le roi de la Rumba". Afrik (in French). Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- AMS (November 2011). "Koffi Olomide – Dance the Night Away With Congolese Soukous". African Music Safari (AMS). Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- News, BBC (23 July 2016). "Koffi Olomide case: Kenya deports singer over airport 'kick'". London: British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - Idris Mukhtar for (25 July 2016). "Koffi Olomide apologizes for kicking dancer". CNN.

- "Koffi Olomidé guilty of rape of 15-year-old girl". BBC News. March 18, 2019.

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Koffi Olomide - NYATAQUANCE [Clip Officiel]". YouTube.