Jaffna kingdom

The Jaffna kingdom (Tamil: யாழ்ப்பாண அரசு, Sinhala: යාපනය රාජධානිය; 1215–1624 CE), also known as Kingdom of Aryachakravarti, was a historical kingdom of what today is northern Sri Lanka. It came into existence around the town of Jaffna on the Jaffna peninsula and was traditionally thought to have been established after the invasion of Kalinga Magha from Kalinga in India.[2][3][4][5] Established as a powerful force in the north, northeast and west of the island, it eventually became a tribute-paying feudatory of the Pandyan Empire in modern South India in 1258, gaining independence[2][6] when the last Pandyan ruler of Madurai was defeated and expelled in 1323 by Malik Kafur, the army general of the Delhi Sultanate.[7] For a brief period in the early to mid-14th century it was an ascendant power in the island of Sri Lanka, to which all regional kingdoms accepted subordination. However, the kingdom was overpowered by the rival Kotte kingdom around 1450 when it was invaded by Prince Sapumal under the orders of Parakramabahu VI.[6][2][3][4][5]

Kingdom of Jaffna | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1215–1619 | |||||||||||||

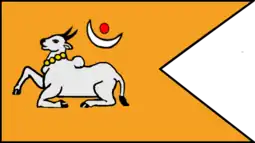

A reconstruction of the Jaffna kingdom flag (Nandi Kodi) based on archaeological and literary evidence.[1] | |||||||||||||

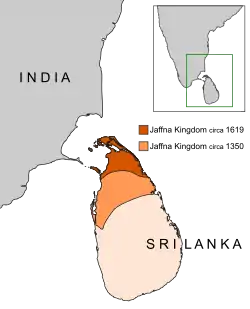

Jaffna kingdom at its greatest extent (circa 1350)

Jaffna kingdom in 1619 | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Nallur | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Tamil | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism (Shaivism) | ||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||

| Aryacakravarti | |||||||||||||

| Cinkaiariyan Cekaracacekaran I a.k.a. Kalinga Magha[2][3][4][5] | |||||||||||||

• 1617–1619 | Cankili II | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Transitional period | ||||||||||||

| 1215 | |||||||||||||

• Independence from Pandya dynasty | 1323 | ||||||||||||

| 1450 | |||||||||||||

• Aryacakravarti dynasty restored | 1467 | ||||||||||||

| 1619 | |||||||||||||

| Currency | Setu coins | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

It gained independence from Kingdom of Kotte control in 1467,[8] and its subsequent rulers directed their energies towards consolidating its economic potential by maximising revenue from pearls, elephant exports and land revenue.[9][10] It was less feudal than most of the other regional kingdoms on the island of Sri Lanka of the period.[10] During this period, important local Tamil literature was produced and Hindu temples were built, including an academy for language advancement.[11][12][13] The Sinhalese Nampota dated in its present form to the 14th or 15th century CE suggests that the whole of the Jaffna Kingdom, including parts of the modern Trincomalee District, was recognised as a Tamil region by the name Demala-pattanama (Tamil city).[14] In this work, a number of villages that are now situated in the Jaffna, Mullaitivu and Trincomalee districts are mentioned as places in Demala-pattanama.[15]

The arrival of the Portuguese on the island of Sri Lanka in 1505, and its strategic location in the Palk Strait connecting all interior Sinhalese kingdoms to South India, created political problems. Many of its kings confronted and ultimately made peace with the Portuguese. In 1617, Cankili II, a usurper to the throne, confronted the Portuguese but was defeated, thus bringing the kingdom's independent existence to an end in 1619.[16][17] Although rebels like Migapulle Arachchi—with the help of the Thanjavur Nayak kingdom—tried to recover the kingdom, they were eventually defeated.[18][19] Nallur, a suburb of modern Jaffna town, was its capital.

History

| Historical states of Sri Lanka |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Sri Lankan Tamils |

|---|

Founding

The origin of the Jaffna kingdom is obscure and still the subject of controversy among historians.[20][21][22][23][24] Among mainstream historians, such as K. M. de Silva, S. Pathmanathan and Karthigesu Indrapala, the widely accepted view is that the kingdom of the Aryacakravarti dynasty in Jaffna began in 1215 with the invasion of a previously unknown chieftain called Magha, who claimed to be from Kalinga in modern India.[3][4][5] He deposed the ruling Parakrama Pandyan II, a foreigner from the Pandyan Dynasty who was ruling the Kingdom of Polonnaruwa at the time with the help of his soldiers and mercenaries from the Kalinga, modern Kerala and Damila (Tamil Nadu) regions in India.[2]

.png.webp)

After the conquest of Rajarata, he moved the capital to the Jaffna peninsula which was more secured by heavy Vanni forest and ruled as a tribute-paying subordinate of the Chola empire of Tanjavur, in modern Tamil Nadu, India.[2] During this period (1247), a Malay chieftain from Tambralinga in modern Thailand named Chandrabhanu invaded the politically fragmented island.[2] Although King Parakramabahu II (1236–1270) from Dambadeniya was able to repulse the attack, Chandrabhanu moved north and secured the throne for himself around 1255 from Magha.[2] Sadayavarman Sundara Pandyan I invaded Sri Lanka in the 13th century and defeated Chandrabhanu the usurper of the Jaffna kingdom in northern Sri Lanka.[25] Sadayavarman Sundara Pandyan I forced Chandrabhanu to submit to the Pandyan rule and to pay tributes to the Pandyan Dynasty. But later on when Chandrabhanu became powerful enough he again invaded the Singhalese kingdom but he was defeated by the brother of Sadayavarman Sundara Pandyan I called Veera Pandyan I and Chandrabhanu lost his life.[25] Sri Lanka was invaded for the 3rd time by the Pandyan Dynasty under the leadership of Arya Cakravarti who established the Jaffna kingdom.[25]

Aryacakravarti dynasty

When Chandrabhanu embarked on a second invasion of the south, the Pandyas came to the support of the Sinhalese king and killed Chandrabhanu in 1262 and installed Aryacakravarti, a minister in charge of the invasion, as the king.[2] When the Pandyan Empire became weak due to Muslim invasions, successive Aryacakravarti rulers made the Jaffna kingdom independent and a regional power to reckon with in Sri Lanka.[2][6] All subsequent kings of the Jaffna kingdom claimed descent from one Kulingai Cakravarti who is identified with Kalinga Magha by Swami Gnanaprakasar and Mudaliar Rasanayagam while maintaining their Pandyan progenitor's family name.[26][27]

Politically, the dynasty was an expanding power in the 13th and 14th century with all regional kingdoms paying tribute to it.[6] However, it met with simultaneous confrontations with the Vijayanagar empire that ruled from Vijayanagara, southern India, and a rebounding Kingdom of Kotte from the south of Sri Lanka.[28] This led to the kingdom becoming a vassal of the Vijayanagar Empire as well as briefly losing its independence under the Kotte kingdom from 1450 to 1467.[6] The kingdom was re-established with the disintegration of Kotte kingdom and the fragmentation of Vijayanagar Empire.[8] It maintained very close commercial and political relationships with the Thanjavur Nayakar kingdom in southern India as well as the Kandyan and segments of the Kotte kingdom. This period saw the building of Hindu temples and a flourishing of literature, both in Tamil and Sanskrit.[28][29][30]

Kotte conquest and restoration

The Kotte conquest of the Jaffna kingdom was led by king Parakramabahu VI's adopted son, Prince Sapumal. This battle took place in many stages. Firstly, the tributaries to the Jaffna kingdom in the Vanni area, namely the Vanniar chieftains of the Vannimai were neutralised. This was followed by two successive conquests. The first war of conquest did not succeed in capturing the kingdom. It was the second conquest dated to 1450 that eventually was successful. Apparently connected with this war of conquest was an expedition to Adriampet in modern South India, occasioned according to Valentyn by the seizure of a Lankan ship laden with cinnamon. The Tenkasi inscription of Arikesari Parakrama Pandya of Tinnevelly who saw the backs of kings at Singai, Anurai, and elsewhere, may refer to these wars; it is dated between 1449–50 and 1453–54.[31] Kanakasooriya Cinkaiariyan the Aryacakravarti king fled to South India with his family. After the departure of Sapumal Kumaraya to Kotte, Kanakasooriya Cinkaiarian re-took the kingdom in 1467.

Decline & dissolution

Portuguese traders reached Sri Lanka by 1505 where their initial forays were against the south-western coastal Kotte kingdom due to the lucrative monopoly on trade in spices that the Kotte kingdom enjoyed that was also of interest to the Portuguese.[32] The Jaffna kingdom came to the attention of Portuguese officials in Colombo for multiple reasons which included their interference in Roman Catholic missionary activities,[32] (which was assumed to be patronizing Portuguese interests) and their support to anti-Portuguese factions of the Kotte kingdom, such as the chieftains from Sittawaka.[32] The Jaffna kingdom also functioned as a logistical base for the Kandyan kingdom, located in the central highlands without access to any seaports, as an entrypot for military aid arriving from South India.[32] Further, due to its strategic location, it was feared that the Jaffna kingdom may become a beachhead for the Dutch landings.[32] It was king Cankili I who resisted contacts with the Portuguese and even massacred 600–700 Parava Catholics in the island of Mannar. These Catholics were brought from India to Mannar to take over the lucrative pearl fisheries from the Jaffna kings.[33][34]

Client state

The first expedition led by Viceroy Dom Constantino de Bragança in 1560 failed to subdue the kingdom but wrestedMannar Island from it.[35] Although the circumstances are unclear, by 1582 the Jaffna king was paying a tribute of ten elephants or an equivalent in cash.[32][35] In 1591, during the second expedition led by André Furtado de Mendonça, king Puvirasa Pandaram was killed and his son Ethirimanna Cinkam was installed as the monarch. This arrangement gave the Catholic missionaries freedom and a monopoly in elephant exports to the Portuguese,[35][36] which the incumbent king however resisted.[35][36] He helped the Kandyan kingdom under kings Vimaladharmasuriya I and Senarat during the period 1593–1635 with the intent of securing help from South India to resist the Portuguese. He however maintained autonomy of the kingdom without overly provoking the Portuguese.[35][36]

Cankili II the usurper

With the death of Ethirimana Cinkam in 1617, his 3-year-old son was the proclaimed king with the late king's brother Arasakesari as regent. Cankili II, a usurper, and nephew of the late king killed all the princes of royal blood including Arasakesari and the powerful chief Periya Pillai Arachchi.[16][37] His cruel actions made him unpopular leading to a revolt by the nominal Christian Mudaliyars Dom Pedro and Dom Luis (also known as Migapulle Arachchi, the son of Periya Pillai Arachchi) and drove Cankili to hide in Kayts in August–September 1618.[38] Unable to secure Portuguese acceptance of his kingship and to suppress the revolt, Cankili II invited military aid from the Thanjavur Nayaks who sent a troop of 5000 men under the military commander Varunakulattan.[16][39][40]

Cankili II was supported by the Kandy rulers. After the fall of the Jaffna kingdom, the two unnamed princesses of Jaffna had been married to Senarat's stepsons, Kumarasingha and Vijayapala.[19] Cankili II expectably received military aid from the Thanjavur Nayak Kingdom. On his part, Raghunatha Nayak of Thanjavur made attempts to recover the Jaffna kingdom for his protege, the Prince of Rameshwaram.[19] However, all attempts to recover the Jaffna kingdom from the Portuguese met with failure.

By June 1619, there were two Portuguese expeditions: a naval expedition that was repulsed by the Karaiyars and another expedition by Filipe de Oliveira and his 5,000 strong land army which was able to inflict defeat on Cankili II.[16] Cankili, along with every surviving member of the royal family were captured and taken to Goa, where he was hanged. The remaining captives were encouraged to become monks or nuns in the holy orders, and as most obliged, it avoided further claimants to the Jaffna throne.[16] In 1620 Migapulle Arachchi, with a troop of Thanjavur soldiers, revolted against the Portuguese and was defeated.[41] A second rebellion was led by a chieftain called Varunakulattan with the support of Raghunatha Nayak.[42]

Administration

According to Ibn Batuta, a traveling Moroccan historian of note, by 1344, the kingdom had two capitals: one in Nallur in the north and the other in Puttalam in the west during the pearling season.[6][30][44] The kingdom proper, that is the Jaffna peninsula, was divided into various provinces with subdivisions of parrus meaning property or larger territorial units and ur or villages, the smallest unit, was administered on a hierarchical and regional basis.[45] At the summit was the king whose kingship was hereditary; he was usually succeeded by his eldest son. Next in the hierarchy stood the adikaris who were the provincial administrators.[6][45] Then came the mudaliyars who functioned as judges and interpreters of the laws and customs of the land.[45] It was also their duty to gather information of whatever was happening in the provinces and report to higher authorities. The title was bestowed on the Karaiyar generals who commanded the navy and also on Vellalar chiefs.[46] Administrators of revenues called kankanis or superintendents and kanakkappillais or accountants came next in line. These were also known as pandarapillai. They had to keep records and maintain accounts.[45][47] The royal heralds whose duty was to convey messages or proclamations came from the Paraiyar community.[48]

Maniyam was the chief of the parrus.[45] He was assisted by mudaliyars who were in turn assisted by udaiyars, persons of authority over a village or a group of villages.[45] They were the custodians of law and order and gave assistance to survey land and collect revenues in the area under their control.[45] The village headman was called talaiyari, pattankaddi or adappanar and he assisted in the collection of taxes and was responsible for the maintenance of order in his territorial unit.[45][49] The Adappanar were the headmen of the ports.[50] The Pattankaddi and Adappanar were from the maritime Karaiyar and Paravar communities.[51] In addition, each caste had a chief who supervised the performance of caste obligations and duties.[45][47]

- Relationship with feudatories

Vannimais were regions south of the Jaffna peninsula in the present-day North Central and Eastern provinces and were sparsely settled by people. They were ruled by petty chiefs calling themselves Vanniar.[47] Vannimais just south of the Jaffna peninsula and in the eastern Trincomalee district usually paid an annual tribute to the Jaffna kingdom instead of taxes.[8][47] The tribute was in cash, grains, honey, elephants, and ivory. The annual tribute system was enforced due to the greater distance from Jaffna.[47] During the early and middle part of the 14th century, the Sinhalese kingdoms in western, southern and central part of the island also became feudatories until the kingdom itself was briefly occupied by the forces of Parakramabahu VI around 1450 for about 17 years.[52] Around the early 17th century, the kingdom also administered an exclave in Southern India called Madalacotta.[53]

Economy

The economy of the kingdom was almost exclusively based on subsistence agriculture until the 15th century. After the 15th century, however, the economy became diversified and commercialized as it became incorporated into the expanding Indian Ocean.

Ibn Batuta, during his visit in 1344, observed that the kingdom of Jaffna was a major trading kingdom with extensive overseas contacts, who described that the kingdom had a "considerable forces by the sea", testifying to their strong reputed navy.[54] The kingdom's trades were oriented towards maritime South India, with which it developed a commercial interdependence. The non-agriculture tradition of the kingdom became strong as a result of large coastal fishing and boating population and growing opportunities for seaborne commerce. Influential commercial groups, drawn mainly from south Indian mercantile groups as well as other, resided in the royal capital, port, and market centers. Artisan settlements were also established and groups of skilled tradesmen—carpenters, stonemasons, wavers, dryers, gold and silver smiths—resided in urban centers. Thus, a pluralistic socio-economic tradition of agriculture marine activities, commerce and handicraft production was well established.[9]

Jaffna kingdom was less feudalized than other kingdoms in Sri Lanka, such as Kotte and Kandy.[10] Its economy was based on more money transactions than transactions on land or its produce. The Jaffna defense forces were not feudal levies; soldiers in the kings service were paid in cash.[10] The king's officials, namely Mudaliayars, were also paid in cash and the numerous Hindu temples seem not to have owned extensive properties, unlike the Buddhist establishments in the South. Temples and the administrators depended on the king and the worshippers for their upkeep.[10] Royal and Army officials were thus a salaried class and these three institutions consumed over 60% of the revenues of the kingdom and 85% of the government expenditures.[10] Much of the kingdom's revenues also came from cash except the Elephants from the Vanni feudatories.[10] At the time of the conquest by the Portuguese in 1620, the kingdom which was truncated in size and restricted to the Jaffna peninsula had revenues of 11,700 pardaos of which 97% came from land or sources connected to the land. One was called land rent and another called paddy tax called arretane.[10]

Apart from the land related taxes, there were other taxes, such as Garden tax from compounds where, among others, plantain, coconut and arecanut palms were grown and irrigated by water from the well. Tree tax on trees such as palmyrah, margosa and iluppai and Poll tax equivalent to a personal tax from each. Professional tax was collected from members of each caste or guild and commercial taxes consisting of, among others, stamp duty on clothes (clothes could not be sold privately and had to have official stamp), Taraku or levy on items of food, and Port and customs duties. Columbuthurai, which connected the Peninsula with the mainland at Poonakari with its boat services, was one of the chief port, and there were customs check posts at the sand passes of Pachilaippalai.[45] Elephants from the southern Sinhalese kingdoms and the Vanni region were brought to Jaffna to be sold to foreign buyers. They were shipped abroad from a bay called Urukathurai, which is now called Kayts—a shortened form of Portuguese Caes dos elephantess (Bay of Elephants).[32] Perhaps a peculiarity of Jaffna was the levy of license fee for the cremation of the dead.[45]

Not all payments in kind were converted to cash, offerings of rice, bananas, milk, dried fish, game meat and curd persisted.[10] Some inhabitants also had to render unpaid personal services called uliyam.[10]

The kings also issued many types of coins for circulation. Several types of coins categorized as Sethu Bull coins issued from 1284 to 1410 are found in large quantities in the northern part of Sri Lanka. The obverse of these coins have a human figure flanked by lamps and the reverse has the Nandi (bull) symbol, the legend Setu in Tamil with a crescent moon above.[5][55]

Culture

Religion

Saivism (a denomination of Hinduism) in Sri Lanka has had continuous history from the early period of settlers from India. Hindu worship was widely accepted even as part of the Buddhist religious practices.[56] During the Chola period in Sri Lanka, around the 9th and 10th century, Hinduism gained status as an official religion in the island kingdom.[57] Kalinga Magha, whose rule followed that of the Cholas is remembered as a Hindu revivalist by the native literature of that period.[58]

As the state religion, Hinduism enjoyed all the prerogatives of the establishment during the period of the Jaffna kingdom. The Aryacakravarti dynasty was very conscious of its duties as a patron towards Hinduism because of the patronage given by its ancestors to the Rameswaram temple, a well-known pilgrimage center of Indian Hinduism. As noted, one of the titles assumed by the kings was Setukavalan or protector of Setu another name for Rameswaram. Setu was used in their coins as well as in inscriptions as marker of the dynasty.[11]

.jpg.webp)

Sapumal Kumaraya (also known as Chempaha Perumal in Tamil), who ruled the Jaffna kingdom on behalf of the Kotte kingdom is credited with either building or renovating the Nallur Kandaswamy temple.[8][59] Singai Pararasasegaram is credited with building the Sattanathar temple, the Vaikuntha Pillaiyar temple and the Veerakaliamman temple. He built a pond called Yamuneri and filled it with water from the Yamuna river of North India, which is considered holy by Hindus.[12] He was a frequent the visitor of the Koneswaram temple, as was his son and successor King Cankili I.[60] King Jeyaveera Cinkaiariyan had the traditional history of the temple compiled as a chronicle in verse, entitled Dakshina Kailasa Puranam, known today as the Sthala Puranam of Koneshwaram Temple.[61] Major temples were normally maintained by the kings and a salary was paid from the royal treasury to those who worked in the temple, unlike in India and rest of Sri Lanka, where religious establishments were autonomous entities with large endowments of land and related revenue.[10]

Most accepted Lord Shiva as the primary deity and the lingam, the universal symbol of Shiva, was consecrated in shrines dedicated to him. The other Hindu gods of the pantheon such as Murugan, Pillaiyar, Kali were also worshipped. At the village level, village deities were popular along with the worship of Kannaki whose veneration was common amongst the Sinhalese in the south as well. Belief in charm and evil spirits existed, just as in the rest of South Asia.[11]

There were many Hindu temples within the kingdom. Some were of great historic importance, such as the Koneswaram temple in Trincomalee, Ketheeswaram temple in Mannar, Naguleswaram temple in Keerimalai along with hundreds of other temples that were scattered over the region.[62] The ceremonies and festivals were similar to those in modern South India, with some slight changes in emphasis. The Tamil devotional literature of Saiva saints was used in worship. The Hindu New Year falling on the middle of April was more elaborately celebrated and festivals, such as Navarattiri, Deepavali, Sivarattiri, and Thaiponkal, along with marriages, deaths and coming of age ceremonies were part of the daily life.[63]

Until ca. 1550, when Cankili I expelled the Buddhists of Jaffna, who were all Sinhalese, and destroyed their many places of worship, Buddhism prevailed in the Jaffna kingdom, among the Sinhalese who had remained in the territory.[64][65][66] Some important places of Buddhist worship in the Jaffna kingdom, which are mentioned in the Nampota are: Naga-divayina (Nagadipa, modern Nainativu), Telipola, Mallagama, Minuvangomu-viharaya and Kadurugoda (modern Kantharodai),[67][68] of these only the Buddhist temple at Nagadipa survive today.[68]

Society

- Caste structure

The social organization of the people of the Jaffna kingdom was based on a caste system and a matrilineal kudi (clan) system similar to the caste structure of South India.[69][70] The Aryacakravarti kings and their immediate family claimed Brahma-Kshatriya status, meaning Brahmins who took to martial life.[71] The Madapalli were the palace stewards and cooks, the Akampadayar's formed the palace servants, the Paraiyar were the royal heralds and the Siviyar were the royal palanquin bearers.[48][72][73] The army and navy generals were from the Karaiyar caste, who also controlled the pearl trade and whose chiefs were known as Mudaliyar, Paddankatti and Adapannar.[74] The Mukkuvar and Thimilar were also engaged in the pearl fishery.[75] The Udayars or village headmen and landlords of agriculture societies were mostly drawn from the Vellalar caste.[49][57] The service providing communities were known as Kudimakkal and consisted of various groups such as the Ambattar, Vannar, Kadaiyar, Pallar, Nalavar, Paraiyar, Koviyar and Brahmin.[76] The Kudimakkal had ritual importance in the temples and at funerals and weddings.[77] The Chettys were well known as traders and owners of Hindu temples and the Pallar and Nalavar castes composed of the agriculturist labours who tilled the land.[57] The weavers were the Paraiyars and Sengunthar who gave importance to the textile trade.[48] The artisans also known as Kammalar were formed by the Kollar, Thattar, Tatchar, Kaltatchar and the Kannar.[78][79]

- Foreign mercenaries & traders

%252C_Neduntheevu.JPG.webp)

Mercenaries of various ethnic and caste backgrounds from India, such as the Telugus (known locally as Vadugas) and Malayalees from the Kerala region were also employed by the king as soldiers.[57] Muslim traders and sea pirates of Mapilla and Moor ethnicities as well as Sinhalese were in the Kingdom.[6][80] The kingdom also functioned as a refuge for rebels from the south seeking shelter after failed political coups. According to the earliest historiographical literature of the Kingdom of Jaffna, Vaiyaapaadal, datable to 14th–15th century, in verse 77 lists the community of Papparavar (Berbers specifically and Africans in general) along with Kuchchiliyar (Gujaratis) and Choanar (Arabs) and places them under the caste category of Pa’l’luvili who are believed to be cavalrymen of Muslim faith . The caste of Pa’l’luvili or Pa’l’livili is peculiar to Jaffna. A Dutch census taken in 1790 in Jaffna records 196 male adults belonging to Pa’l’livili caste as taxpayers. That means the identity and profession existed until Dutch times. But, Choanakar, with 492 male adults and probably by this time generally meaning the Muslims, is found mentioned as a separate community in this census.[81]

- Laws

During the rule of the Aryacakravarti rulers, the laws governing the society was based on a compromise between a matriarchal system of society that seemed to have had deeper roots overlaid with a patriarchal system of governance. These laws seemed to have existed side by side as customary laws to be interpreted by the local Mudaliars. In some aspects such as in inheritance the similarity to Marumakattayam law of present-day Kerala and Aliyasanatana of modern Tulunadu was noted by later scholars. Further Islamic jurisprudence and Hindu laws of neighboring India also seemed to have affected the customary laws. These customary laws were later codified and put to print during the Dutch colonial rule as Thesavalamai in 1707.[82] The rule under earlier customs seemed to have been females succeeded females. But when the structure of the society came to be based on patriarchal system, a corresponding rule was recognized, that males succeeded males. Thus, we see the devolution of muthusam (paternal inheritance) was on the sons, and the devolution of the chidenam (dowry or maternal inheritance) was on the females. Just as one dowried sister succeeded another, we had the corresponding rule that if one's brother died instate, his properties devolved upon his brothers to the exclusion of his sisters. The reason being that in a patriarchal family each brother formed a family unit, but all the brothers being agnates, when one of them died his property devolved upon his agnates.[82]

Literature

The kings of the dynasty provided patronage to literature and education. Temple schools and traditional gurukulam classes in verandahs (known as Thinnai Pallikoodam in Tamil language) spread basic education in languages such as Tamil language and Sanskrit and religion to the upper classes.[13] During the reign of Jeyaveera Cinkaiariyan rule, a work on medical science (Segarajasekaram), on astrology (Segarajasekaramalai)[13][83] and on mathematics (Kanakathikaram) were authored by Karivaiya.[13] During the rule of Gunaveera Cinkaiariyan, a work on medical sciences, known as Pararajasekaram, was completed.[13] During Singai Pararasasegaram's rule, an academy for Tamil language propagation on the model of ancient Tamil Sangams was established in Nallur. This academy performed a useful service in collecting and preserving ancient Tamil works in manuscripts form in a library called Saraswathy Mahal.[13] Singai Pararasasekaran's cousin Arasakesari was credited with translating the Sanskrit classic Raghuvamsa into Tamil.[83] Pararasasekaran's brother Segarajasekaran and Arasakesari collected manuscripts from Madurai and other regions for the Saraswathy Mahal library.[84] Among other literary works of historic importance compiled before the arrival of European colonizers, Vaiyapatal, written by Vaiyapuri Aiyar, is well known.[13][85]

Architecture

There were periodic waves of South Indian influence over Sri Lankan art and architecture, though the prolific age of monumental art and architecture seemed to have declined by the 13th century.[87] Temples built by the Tamils of Indian origin from the 10th century belonged to the Madurai variant of Vijayanagar period.[87] A prominent feature of the Madurai style was the ornate and heavily sculptured tower or gopuram over the entrance of temple.[87] None of the important religious constructions of this style within the territory that formed the Jaffna kingdom survived the destructive hostility of the Portuguese.[87]

Nallur, the capital was built with four entrances with gates.[88] There were two main roadways and four temples at the four gateways.[88] The rebuilt temples that exist now do not match their original locations which instead are occupied by churches erected by the Portuguese.[88] The center of the city was Muthirai Santhai (market place) and was surrounded by a square fortification around it.[88] There were courtly buildings for the Kings, Brahmin priests, soldiers and other service providers.[88] The old Nallur Kandaswamy temple functioned as a defensive fort with high walls.[88] In general, the city was laid out like the traditional temple town according to Hindu traditions.[88]

See also

Notes

- Mudaliyar C, Rasanayagam (1993). Ancient Jaffna: being a research into the history of Jaffna from very early times to the Portuguese period. New Delhi Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120602106.

- de Silva, A History of Sri Lanka, pp. 91–92

- Nadarajan, V. History of Ceylon Tamils, p. 72

- Indrapala, K. Early Tamil Settlements in Ceylon, p. 16

- Coddrington, K. Ceylon coins and currency, pp. 74–76

- Peebles, History of Sri Lanka, pp. 31–32

- The History of Sri Lanka by Patrick Peebles, p. 31

- Peebles, History of Sri Lanka, p. 34

- Pfaffenberger, B .The Sri Lankan Tamils, pp. 30–31

- Abeysinghe, T. Jaffna Under the Portuguese, pp. 29–30

- Gunasingam, M. Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism, p. 63

- Kunarasa, K. The Jaffna Dynasty, pp. 73–74

- Gunasingam, M. Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism, pp. 64–65

- Indrapala, K – The Evolution of an Ethnic Identity: The Tamils in Sri Lanka C. 300 BCE to C. 1200 CE. Colombo: Vijitha Yapa.

- "Nampota". Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- Abeysinghe, T. Jaffna Under the Portuguese, pp. 58–63

- Gnanaprakasar, S. A critical history of Jaffna, pp. 153–172

- An historical relation of the island Ceylon, Volume 1, by Robert Knox and JHO Paulusz, pp. 19–47.

- An historical relation of the island Ceylon, Volume 1, by Robert Knox and JHO Paulusz, p. 43.

- Gunasingam, M. Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism, p. 53

- Manogaran, C. The untold story of Ancient Tamils of Sri Lanka, pp. 22–65

- Kunarasa, K. The Jaffna Dynasty, pp. 1–53

- Rasanayagam, M. Ancient Jaffna, pp. 272–321

- "The so-called Tamil Kingdom of Jaffna". S. Ranwella. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- Sri Lanka and South-East Asia: Political, Religious and Cultural Relations by W.M. Sirisena, p. 57

- Kunarasa, K. The Jaffna Dynasty, pp. 65–66

- Coddrington, Short history of Ceylon, pp. 91–92

- de Silva, A History of Sri Lanka, pp. 132–133

- Kunarasa, K. The Jaffna Dynasty, pp. 73–75

- Codrington, Humphry William. "Short history of Sri Lanka: Dambadeniya and Gampola Kings (1215–1411)". Lakdiva.org. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- Humphrey William Codrington, A Short History of Ceylon Ayer Publishing, 1970; ISBN 0-8369-5596-X

- Abeysinghe, T. Jaffna Under the Portuguese, p. 2

- Kunarasa, K. The Jaffna Dynasty, pp. 82–84

- Gnanaprakasar, S. A critical history of Jaffna, pp. 113–117

- Abeysinghe, T. Jaffna Under the Portuguese, p. 3

- de Silva, A History of Sri Lanka, p. 166

- Vriddhagirisan, V. (1942). The Nayaks of Tanjore. Annamalai University: Annamalai University Historical Series. p. 80. ISBN 9788120609969.

- DeSilva, Chandra Richard (1972). The Portuguese in Ceylon, 1617–1638. University of London: School of Oriental and African Studies. p. 96.

- De Queyroz, The Temporal and Spiritual Conquest of Ceylon, pp. 51, 468

- Journal of Tamil Studies. International Institute of Tamil Studies. 1981. pp. 44–45.

- Abeyasinghe, Tikiri (1986). Jaffna under the Portuguese. Lake House Investments. ISBN 9789555520003.

- Vriddhagirisan, V. (1995). Nayaks of Tanjore. Asian Educational Services. p. 91. ISBN 9788120609969.

- Kunarasa, K. The Jaffna Dynasty, p. 2

- Gunasingam, M. Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism, p. 54

- "Yarl-Paanam". Eelavar Network. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 24 November 2007.

- Rasanayagam, C. (1933). History of Jaffna யாழ்ப்பாணச் சரித்திரம் (in Tamil). ஏசியன் எடுகேஷனல் சர்வீசஸ். p. 17.

தமிழரசர்காலத்திற் போலவே "அதிகாரம்' என்னுந் தலைமைக்காரர் பறங்கியர் காலத்திலும் நியமிக் கப்பட்டிருந்தாலும், வரியறவிடும் முக்கிய தலைமைக் காரர், இறைசுவர் (Recebedor) என்றும், அவர்களுக்குக் கீழுள்ளவர்கள் 'தலையாரிகள்' அல்லது மேயோருல், (Mayora) என்றும் அழைக்கப்பட்டார்கள். உத்தியோகங்களெல்லாம் உயர்ந்த சாதித் தலைவர்களுக்கே கொடுக்கப்பட்டன. தமிழரசர் காலத்தில் கப்பற்படைக்கு அதிபதிகளாயிருந்த கரையார்த் தலைவருக்கும், வேளாளருக்கு உதவியதுபோல் முதலியார்ப் பட்டமுங் கண்ணியமான உத்தியோகங்களுக்கு கொடுக்கப்பட்டன.

- Gunasingam, M. Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism, p. 58

- Ragupathy, Ponnampalam (1987). Early Settlements in Jaffna: An Archaeological Survey. University of Jaffna: Thillimalar Ragupathy. pp. 167, 210.

- K, Arunthavarajah (March 2014). "The Administration of Jaffna Kingdom – A Historical View" (PDF). International Journal of Business and Administration Research Review. University of Jaffna. 2 (3): 32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Bastiampillai, Bertram (1 January 2006). Northern Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in the 19th century. Godage International Publishers. p. 94. ISBN 9789552088643.

- K., Arunthavarajah (2014). "The Administration of the Jaffna Kingdom – A Historical View". International Journal of Business and Administration Research. University of Jaffna: Department of History. 2: 28–34 – via IJBARR.

- de Silva, A History of Sri Lanka, p. 117

- Abeysinghe, T. Jaffna Under the Portuguese, p. 28

- Raghavan, M. D. (1971). Tamil culture in Ceylon: a general introduction. Kalai Nilayam. p. 140.

- V. Sundaram. "Rama Sethu: Historic facts vs political fiction". News Today. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- Parker, H. Ancient Ceylon: An Account of the Aborigines and of Part of the Early Civilisation, pp. 65, 115, 148

- Gunasingam, M. Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism, p. 62

- Codrington, Humphry William. "The Polonaruwa Kings, (1070–1215)". Lakdiva.org. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- Gnanaprakasar, S. A critical history of Jaffna, p. 103

- Pieris, Paulus Edward (1983). Ceylon, the Portuguese era: being a history of the island for the period, 1505–1658. Vol. 1. Sri Lanka: Tisara Prakasakayo. p. 262. OCLC 12552979.

- Navaratnam, C.S. (1964). A Short History of Hinduism in Ceylon. Jaffna. pp. 43–47. OCLC 6832704.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gunasingam, Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism, p. 65

- Gunasingam, Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism, p. 66

- Wilhelm Geiger Culture of Ceylon in mediaeval times, Edited by Heinz Bechert, p. 8

- C. Rasanayagam, Ancient Jaffna: being a research into the history of Jaffna, pp. 382–383

- De Silva, Chandra Richard Sri Lanka and the Maldive Islands, p. 128

- Seneviratna, Anuradha Anusmrti: thoughts on Sinhala culture and civilization, Volume 2

- Indrapala, Karthigesu Evolution of an Ethnic Identity, (2005), p. 210

- Rōhaṇa. University of Ruhuna. 1991. p. 35.

- Wickramasinghe, Nira (2014). Sri Lanka in the Modern Age: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-025755-2.

- Gnanaprakasar, S. A critical history of Jaffna, p. 96

- Pulavar, Mātakal Mayilvākan̲ap (1995). Mātakal Mayilvākan̲ap Pulavar el̲utiya Yāl̲ppāṇa vaipavamālai (in Tamil). Intu Camaya Kalācāra Aluvalkaḷ Tiṇaikkaḷam.

- Arasaratnam, Sinnappah (1996). Ceylon and the Dutch, 1600–1800: External Influences and Internal Change in Early Modern Sri Lanka. Variorum. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-86078-579-8.

- Raghavan, M.D. (1964). India in Ceylonese History: Society, and Culture. Asia Publishing House. p. 143.

- Hussein, Asiff (2007). Sarandib: an ethnological study of the Muslims of Sri Lanka. Asiff Hussein. p. 479. ISBN 978-9559726227.

- David, Kenneth (1977). The New Wind: Changing Identities in South Asia. Walter de Gruyter. p. 195. ISBN 978-3-11-080775-2.

- Nayagam, Xavier S. Thani (1959). Tamil Culture. Academy of Tamil Culture. p. 109.

- Ramaswamy, Vijaya (2017). Historical Dictionary of the Tamils. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-5381-0686-0.

- Perinbanayagam, R.S. (1982). The karmic theater: self, society, and astrology in Jaffna. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 25. ISBN 9780870233746.

- Abeysinghe, T. Jaffna Under the Portuguese, p. 4

- "Place Name of the Day: Papparappiddi". Tamilnet. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- Tambiah, Laws and customs of Tamils of Jaffna, pp. 18–20.

- Coddrington, H. Ceylon Coins and Currency, p. 74

- Arunachalam, M. (1981). Aintām Ulakat Tamil̲ Mānāṭu-Karuttaraṅku Āyvuk Kaṭṭuraikaḷ. International Association of Tamil Research. pp. 7–158.

- Nadarajan, V. History of Ceylon Tamils, pp. 80–84

- Kunarasa, K. The Jaffna Dynasty, p. 4

- Gunasingam, M. Sri Lankan Tamil Nationalism, p. 64

- V.N. Giritharan. "Nallur Rajadhani: City Layout". Archived from the original on 25 December 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

References

- de Silva, K. M. (2005). A History of Sri Lanka. Colombo: Vijitha Yapa. p. 782. ISBN 955-8095-92-3.

- Abeysinghe, Tikiri (2005). Jaffna under the Portuguese. Colombo: Stamford Lake. p. 66. OCLC 75481767.

- Kunarasa, K (2003). The Jaffna Dynasty. Johor Bahru: Dynasty of Jaffna King's Historical Society. p. 122. ISBN 955-8455-00-8.

- Gnanaprakasar, Swamy (2003). A Critical History of Jaffna. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. p. 122. ISBN 81-206-1686-3.

- Pathmanathan, S (1974). The Kingdom of Jaffna:Origins and early affiliations. Colombo: Ceylon Institute of Tamil Studies. p. 27.

- Gunasingam, Murugar (1999). Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism. Sydney: MV. p. 238. ISBN 0-646-38106-7.

- Nadarajan, Vasantha (1999). History of Ceylon Tamils. Toronto: Vasantham. p. 146.

- Coddrington, H. W. (1994). Short History of Ceylon. New Delhi: AES. p. 290. ISBN 81-206-0946-8.

- Parker, H. (1909). Ancient Ceylon: An Account of the Aborigines and of Part of the Early Civilisation. London: Luzac & Co. p. 695. ISBN 9788120602083. LCCN 81-909073.

- Tambiah, H. W (2001). Laws and customs of Tamils of Jaffna (revised ed.). Colombo: Women's Education & Research Centre. p. 259. ISBN 955-9261-16-9.

- Pfaffenberg, Brian (1994). The Sri Lankan Tamils. U.S.: Westview Press. p. 247. ISBN 0-8133-8845-7.

- Mayilvakanap Pulavar, Matakal (1884). The Yalpana Vaipava Malai, or The History of the Kingdom of Jaffna (First ed.). New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. p. 146. ISBN 978-81-206-1362-1.

- Manogaran, Chelvadurai (2000). The untold story of the ancient Tamils of Sri Lanka. Chennai: Kumaran. p. 81.

- "Yarl-Paanam". Eelavar Network. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. Retrieved 24 November 2007.

- Rasanayagam, Mudaliyar (1926). Ancient Jaffna, being a research into the History of Jaffna from very early times to the Portuguese Period. Everymans Publishers Ltd, Madras (Reprint by New Delhi, AES in 2003). p. 390. ISBN 81-206-0210-2.

- Codrington, Humphry William. "Short history of Sri Lanka:Dambadeniya and Gampola Kings (1215–1411)". Lakdiva.org. Retrieved 25 November 2007.

- Coddrington, H. W. (1996). Ceylon Coins and Currency. New Delhi: Vijitha Yapa. p. 290. ISBN 81-206-1202-7.

- Peebles, Patrick (2006). The History of Sri Lanka. United States: Greenwood Press. p. 248. ISBN 0-313-33205-3.