Penda of Mercia

Penda (died 15 November 655)[1] was a 7th-century king of Mercia, the Anglo-Saxon kingdom in what is today the Midlands. A pagan at a time when Christianity was taking hold in many of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, Penda took over the Severn Valley in 628 following the Battle of Cirencester before participating in the defeat of the powerful Northumbrian king Edwin at the Battle of Hatfield Chase in 633.[2]

| Penda | |

|---|---|

Stained glass window, depicting the death of Penda at the Battle of the Winwaed, Worcester Cathedral | |

| King of Mercia | |

| Reign | c. 626 – 655 AD

or c. 633 – 655 AD or c. 642 – 655 AD |

| Predecessor | Cearl |

| Successor | Peada |

| Born | c. 606 |

| Died | 15 November 655 (aged 48–49) Possibly the Cock Beck, at the Battle of the Winwaed |

| Spouse | Cynewise |

| Issue | Peada Wulfhere Æthelred Merewalh Cyneburh Cyneswith |

| Dynasty | Iclingas |

| Father | Pybba |

| Religion | Pagan |

Nine years later, he defeated and killed Edwin's eventual successor, Oswald, at the Battle of Maserfield; from this point he was probably the most powerful of the Anglo-Saxon rulers of the time, laying the foundations for the Mercian Supremacy over the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. He repeatedly defeated the East Angles and drove Cenwalh the king of Wessex into exile for three years. He continued to wage war against the Bernicians of Northumbria. Thirteen years after Maserfield, he suffered a crushing defeat by Oswald's successor and brother Oswiu, and was killed at the Battle of the Winwaed in the course of a final campaign against the Bernicians.

Sources

The source for Penda's life which can most securely be called the earliest, and which is the most detailed, is Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People (completed c. 731; chapters II.20, III.7, III.16–18, III.21, III.24). Penda also appears prominently in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, whose sources and so reliability for this period are unclear, and in the early ninth-century Historia Brittonum, which adds a little more possibly reliable information to Bede's account.[3] He seems also to be mentioned, as Panna ap Pyd, in the perhaps seventh-century Welsh praise-poem Marwnad Cynddylan, which says of Cynddylan: 'pan fynivys mab pyd mor fu parawd' ('when the son of Pyd wished, how ready was he').[4] Penda and his family seem to have given their names to a number of places in the West Midlands, including Pinbury, Peddimore, and Pinvin.[5]

Etymology

The etymology of the name Penda is unknown. Penda of Mercia is the only person recorded in the comprehensive Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England with this name.[6]

Suggestions for etymologies of the name are essentially divided between a Celtic and a Germanic origin.[7][8] The names of members of a Northumbrian [spiritual] brotherhood are recorded in the ninth-century Liber vitae Dunelmensis; the name Penda occurs in this list and is categorised as a British (Welsh) name.[9] John T. Koch noted that, "Penda and a number of other royal names from early Anglian Mercia have more obvious Brythonic than German explanations, though they do not correspond to known Welsh names."[10] These royal names include those of Penda's father Pybba, and of his son Peada.[11] It has been suggested that the firm alliance between Penda and various British princes might be the result of a "racial cause."[12]

Continental Germanic comparanda for the name include a feminine Penta (9th century) and a toponym Penti-lingen, suggesting an underlying personal name Pendi.[13]

Descent, beginning of reign, and battle with the West Saxons

Penda was a son of Pybba of Mercia and said to be an Icling, with a lineage purportedly extending back to Wōden. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle gives his descent as follows:

Penda was Pybba's offspring, Pybba was Cryda's offspring, Cryda Cynewald's offspring, Cynewald Cnebba's offspring, Cnebba Icel's offspring, Icel Eomer's offspring, Eomer Angeltheow's offspring, Angeltheow Offa's offspring, Offa Wermund's offspring, Wermund Wihtlæg's offspring, Wihtlæg Woden's offspring.[14]

The Historia Brittonum says that Pybba had 12 sons, including Penda, but that Penda and Eowa of Mercia were those best known to its author.[15] (Many of these 12 sons of Pybba may in fact merely represent later attempts to claim descent from him.[16]) Besides Eowa, the pedigrees also give Penda a brother named Coenwalh from whom two later kings were said to descend, although this may instead represent his brother-in-law Cenwalh of Wessex.[17]

The time at which Penda became king is uncertain, as are the circumstances. Another Mercian king, Cearl, is mentioned by Bede as ruling at the same time as the Northumbrian king Æthelfrith, in the early part of the 7th century. Whether Penda immediately succeeded Cearl is unknown, and it is also unclear whether they were related, and if so how closely; Henry of Huntingdon, writing in the 12th century, claimed that Cearl was a kinsman of Pybba.[18] It is also possible that Cearl and Penda were dynastic rivals.[19]

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Penda became king in 626, ruled for 30 years, and was 50 years old at the time of his accession.[14] That he ruled for 30 years should not be taken as an exact figure,[20] since the same source says he died in 655, which would not correspond to the year given for the beginning of his reign unless he died in the thirtieth year of his reign.[21] Furthermore, that Penda was truly 50 years old at the beginning of his reign is generally doubted by historians, mainly because of the ages of his children. The idea that Penda, at about 80 years of age, would have left behind children who were still young (his son Wulfhere was still just a youth three years after Penda's death, according to Bede) has been widely considered implausible.[22] The possibility has been suggested that the Chronicle actually meant to say that Penda was 50 years old at the time of his death, and therefore about 20 in 626.[23]

Bede, in his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, says of Penda that he was "a most warlike man of the royal race of the Mercians" and that, following Edwin of Northumbria's defeat in 633 (see below), he ruled the Mercians for 22 years with varying fortune.[24] The noted 20th-century historian Frank Stenton was of the opinion that the language used by Bede "leaves no doubt that ... Penda, though descended from the royal family of the Mercians, only became their king after Edwin's defeat".[25] The Historia Brittonum accords Penda a reign of only ten years,[26] perhaps dating it from the time of the Battle of Maserfield (see below) around 642, although according to the generally accepted chronology this would still be more than ten years.[21] Given the apparent problems with the dates given by the Chronicle and the Historia, Bede's account of the length of Penda's reign is generally considered the most plausible by historians. Nicholas Brooks noted that, since these three accounts of the length of Penda's reign come from three different sources, and none of them are Mercian (they are West Saxon, Northumbrian, and Welsh), they may merely reflect the times at which their respective peoples first had military involvement with Penda.[20]

The question of whether or not Penda was already king during the late 620s assumes greater significance in light of the Chronicle's record of a battle between Penda and the West Saxons under their kings Cynegils and Cwichelm taking place at Cirencester in 628.[27] If he was not yet king, then his involvement in this conflict might indicate that he was fighting as an independent warlord during this period—as Stenton put it, "a landless noble of the Mercian royal house fighting for his own hand."[28] On the other hand, he might have been one of multiple rulers among the Mercians at the time, ruling only a part of their territory. The Chronicle says that after the battle, Penda and the West Saxons "came to an agreement."[29]

It has been speculated that this agreement marked a victory for Penda, ceding to him Cirencester and the areas along the lower River Severn.[28] These lands to the southwest of Mercia had apparently been taken by the West Saxons from the Britons in 577,[30] and the territory eventually became part of the subkingdom of the Hwicce. Given Penda's role in the area at this time and his apparent success there, it has been argued that the subkingdom of the Hwicce was established by him; evidence to support this is lacking, although the subkingdom is known to have existed later in the century.[31]

Alliance with Cadwallon and the Battle of Hatfield Chase

In the late 620s or early 630s, Cadwallon ap Cadfan, the British (Welsh) king of Gwynedd, became involved in a war with Edwin of Northumbria, the most powerful king in Britain at the time. Cadwallon apparently was initially unsuccessful, but he joined with Penda, who is thought to have been the lesser partner in their alliance,[32] to defeat the Northumbrians in October 633[2] at the Battle of Hatfield Chase. Penda was probably not yet king of the Mercians, but he is thought to have become king soon afterwards, based on Bede's characterisation of his position. Edwin was killed in the battle, and one of his sons, Eadfrith, fell into Penda's hands.[23]

One manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that, following the victory at Hatfield Chase, Cadwallon and Penda went on to ravage "the whole land" of the Northumbrians.[33] Certainly Cadwallon continued the war, but the extent of Penda's further participation is uncertain. Bede says that the pagans who had slain Edwin—presumably a reference to the Mercians under Penda, although conceivably it could be a derisive misnomer meant to refer to the Christian British—burned a church and town at Campodonum,[34] although the time at which this occurred is uncertain. Penda might have withdrawn from the war at some point before the defeat and death of Cadwallon at the Battle of Heavenfield, about a year after Hatfield Chase, since he was not present at this battle. Furthermore, Bede makes no mention of Penda's presence in the preceding siege and battle in which Osric of Deira was defeated and killed. Penda's successful participation in the battle of Hatfield Chase would have elevated his status among the Mercians and so enabled him to become king, and he might have withdrawn from the war before Heavenfield to secure or consolidate his position in Mercia. Referring to Penda's successes against the West Saxons and the Northumbrians, D. P. Kirby writes of Penda's emergence in these years as "a Mercian leader whose military exploits far transcended those of his obscure predecessors."[21]

During the reign of Oswald

Oswald of Bernicia became king of Northumbria after his victory over Cadwallon at Heavenfield.[23] Penda's status and activities during the years of Oswald's reign are obscure, and various interpretations of Penda's position during this period have been suggested. It has been presumed that Penda acknowledged Oswald's authority in some sense after Heavenfield, although Penda was probably an obstacle to Northumbrian supremacy south of the Humber.[35] It has been suggested that Penda's strength during Oswald's reign could be exaggerated by the historical awareness of his later successes.[36] Kirby says that, while Oswald was as powerful as Edwin had been, "he faced a more entrenched challenge in midland and eastern England from Penda".[37]

At some point during Oswald's reign, Penda had Edwin's son Eadfrith killed, "contrary to his oath".[23] The possibility that his killing was the result of pressure from Oswald—Eadfrith being a dynastic rival of Oswald—has been suggested.[35] Since the potential existed for Eadfrith to be put to use in Mercia's favour in Northumbrian power struggles while he was alive, it would not have been to Penda's advantage to have him killed.[38] On the other hand, Penda might have killed Eadfrith for his own reasons. It has been suggested that Penda was concerned that Eadfrith could be a threat to him because Eadfrith might seek vengeance for the deaths of his father and brother;[39] it is also possible that Mercian dynastic rivalry played a part in the killing, since Eadfrith was a grandson of Penda's predecessor Cearl.[19][39]

It was probably at some point during Oswald's reign that Penda fought with the East Angles and defeated them, killing their king Egric and the former king Sigebert, who had been brought out of retirement in a monastery against his will in the belief that his presence would motivate the soldiers.[40] The time at which the battle occurred is uncertain; it may have been as early as 635, but there is also evidence to suggest it could not have been before 640 or 641.[41] Presuming that this battle took place before the Battle of Maserfield, it may have been that such an expression of Penda's ambition and emerging power made Oswald feel that Penda had to be defeated for Northumbrian dominance of southern England to be secured or consolidated.[37]

Penda's brother Eowa was also said by the Historia Brittonum[25] and the Annales Cambriae to have been a king of the Mercians at the time of Maserfield. The question of what sort of relationship of power existed between the brothers before the battle is a matter of speculation. Eowa may have simply been a sub-king under Penda and it is also possible that Penda and Eowa ruled jointly during the 630s and early 640s: joint kingships were not uncommon among Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of the period. They may have ruled the southern and northern Mercians respectively.[38] That Penda ruled the southern part is a possibility suggested by his early involvement in the area of the Hwicce, to the south of Mercia,[42] as well as by the fact that, after Penda's death, his son Peada was allowed to rule southern Mercia while the northern part was placed under direct Northumbrian control.[43]

Another possibility was suggested by Brooks: Penda might have lost power at some point after Heavenfield, and Eowa may have actually been ruling the Mercians for at least some of the period as a subject ally or puppet of Oswald. Brooks cited Bede's statement implying that Penda's fortunes were mixed during his 22 years in power and noted the possibility that Penda's fortunes were low at this time. Thus it may be that Penda was not consistently the dominant figure in Mercia during the years between Hatfield and Maserfield.[44]

Maserfield

On 5 August 642,[45] Penda defeated the Northumbrians at the Battle of Maserfield, which was fought near the lands of the Welsh, and Oswald was killed. Surviving Welsh poetry suggests that Penda fought in alliance with the men of Powys—apparently he was consistently allied with some of the Welsh—perhaps including Cynddylan ap Cyndrwyn, of whom it was said that "when the son of Pyb desired, how ready he was", presumably meaning that he was an ally of Penda, the son of Pybba.[46] If the traditional identification of the battle's location with Oswestry is correct, then this would indicate that it was Oswald who had taken the offensive against Penda. It has been suggested that he was acting against "a threat posed to his domination of Mercia by a hostile alliance of Penda and Powys."[47] According to Reginald of Durham's 12th century Life of Saint Oswald, Penda fled into Wales before the battle, at which point Oswald felt secure and sent his army away. This explanation of events has been regarded as "plausible" but is not found in any other source, and may, therefore, have been Reginald's invention.[48]

According to Bede, Penda had Oswald's body dismembered, with his head, hands and arms being placed onto stakes[49] (this may have had a pagan religious significance[50]); Oswald thereafter came to be revered as a saint, with his death in battle as a Christian king against pagans leading him to be regarded as a martyr.[51]

Eowa was killed at Maserfield along with Oswald,[25] although on which side he fought is unknown. It may well be that he fought as a dependent ally of Oswald against Penda. If Eowa was in fact dominant among the Mercians during the period leading up to the battle, then his death could have marked what the author of the Historia Brittonum regarded as the beginning of Penda's ten-year reign.[22] Thus it may be that Penda prevailed not only over the Northumbrians but also over his rivals among the Mercians.[52]

The Historia Brittonum may also be referring to this battle when it says that Penda first freed (separavit) the Mercians from the Northumbrians. This may be an important clue to the relationship between the Mercians and the Northumbrians before and during Penda's time. There may have existed a "Humbrian confederacy" that included the Mercians until Penda broke free of it.[53] On the other hand, it has been considered unlikely that this was truly the first instance of their separation: it is significant that Cearl had married his daughter to Edwin during Edwin's exile, when Edwin was an enemy of the Northumbrian king Æthelfrith. It would seem that if Cearl was able to do this, he was not subject to Æthelfrith;[23] thus it may be that any subject relationship only developed after the time of this marriage.[53]

The battle left Penda with a degree of power unprecedented for a Mercian king—Kirby called him "without question the most powerful Mercian ruler so far to have emerged in the midlands" after Maserfield[37]—and the prestige and status associated with defeating the powerful Oswald must have been very significant. Northumbria was greatly weakened as a consequence of the battle; the kingdom became fractured to some degree between Deira in its southern part and Bernicia in the north, with the Deirans acquiring a king of their own, Oswine, while in Bernicia, Oswald was succeeded by his brother, Oswiu. Mercia thus enjoyed a greatly enhanced position of strength relative to the surrounding kingdoms. Stenton wrote that the battle left Penda as "the most formidable king in England", and observed that although "there is no evidence that he ever became, or even tried to become, the lord of all the other kings of southern England ... none of them can have been his equal in reputation".[54]

Campaigns between Maserfield and the Winwaed

Defeat at Maserfield must have weakened Northumbrian influence over the West Saxons, and the new West Saxon king Cenwealh—who was still pagan at this time—was married to Penda's sister. It may be surmised that this meant he was to some extent within what Kirby called a "Mercian orbit".[55] However, when Cenwealh (according to Bede) "repudiated" Penda's sister in favour of another wife, Penda drove Cenwealh into exile in East Anglia in 645, where he remained for three years before regaining power.[56] Who governed the West Saxons during the years of Cenwealh's exile is unknown; Kirby considered it reasonable to conclude that whoever ruled was subject to Penda. He also suggested that Cenwealh may not have been able to return to his kingdom until after Penda's death.[55]

In 654,[14] the East Anglian king Anna, who had harboured the exiled Cenwealh, was killed by Penda. He was succeeded by a brother, Aethelhere; since Aethelhere was subsequently a participant in Penda's doomed invasion of Bernicia in 655 (see below), it may be that Penda installed Aethelhere in power.[16] It has been suggested that Penda's wars against the East Angles "should be seen in the light of interfactional struggles within East Anglia."[57] It may also be that Penda made war against the East Angles with the intention of securing Mercian dominance over the area of Middle Anglia,[58] where Penda established his son Peada as ruler.[59]

In the years after Maserfield, Penda also destructively waged war against Oswiu of Bernicia on his own territory. At one point before the death of Bishop Aidan (31 August 651), Bede says that Penda "cruelly ravaged the country of the Northumbrians far and near" and besieged the royal Bernician stronghold of Bamburgh. When the Mercians were unable to capture it—"not being able to enter it by force, or by a long siege"—Bede reports that they attempted to set the city ablaze, but that it was saved by a sacred wind supposedly sent in response to a plea from the saintly Aidan: "Behold, Lord, how great mischief Penda does!" The wind is said to have blown the fire back towards the Mercians, deterring them from further attempts to capture the city.[60] At another point, some years after Aidan's death, Bede records another attack. He says that Penda led an army in devastating the area where Aidan died—he "destroyed all he could with fire and sword"—but that when the Mercians burned down the church where Aidan died, the post against which he was leaning at the time of his death was undamaged; this was taken to be a miracle.[61] No open battles are recorded as being fought between the two sides before the Winwaed in 655 (see below), however, and this may mean that Oswiu deliberately avoided battle due to a feeling of weakness relative to Penda. This feeling may have been in religious as well as military terms: N. J. Higham wrote of Penda acquiring "a pre-eminent reputation as a god-protected, warrior–king", whose victories may have led to a belief that his pagan gods were more effective for protection in war than the Christian God.[35]

Relations with Bernicia; Christianity and Middle Anglia

Despite these apparent instances of warfare, relations between Penda and Oswiu were probably not entirely hostile during this period, since Penda's daughter Cyneburh married Alhfrith, Oswiu's son, and Penda's son Peada married Alhflaed, Oswiu's daughter. According to Bede, who dates the events to 653, the latter marriage was made contingent upon the baptism and conversion to Christianity of Peada; Peada accepted this, and the preaching of Christianity began among the Middle Angles, whom he ruled. Bede wrote that Penda tolerated the preaching of Christianity in Mercia itself, despite his own beliefs:

Nor did King Penda obstruct the preaching of the word among his people, the Mercians, if any were willing to hear it; but, on the contrary, he hated and despised those whom he perceived not to perform the works of faith, when they had once received the faith, saying, "They were contemptible and wretched who did not obey their God, in whom they believed." This was begun two years before the death of King Penda.[62]

Peada's conversion and the introduction of priests into Middle Anglia could be seen as evidence of Penda's tolerance of Christianity, given the absence of evidence that he sought to interfere.[63] On the other hand, an interpretation is also possible whereby the marriage and conversion could be seen as corresponding to a successful attempt on Oswiu's part to expand Bernician influence at Penda's expense; Higham saw Peada's conversion more in terms of political manoeuvring on both sides than religious zeal.[64]

Middle Anglia as a political entity may have been created by Penda as an expression of Mercian power in the area following his victories over the East Angles. Previously there seem to have been a number of small peoples inhabiting the region, and Penda's establishment of Peada as a subking there may have marked their initial union under one ruler. The districts corresponding to Shropshire and Herefordshire, along Mercia's western frontier near Wales, probably also fell under Mercian domination at this time. Here a king called Merewalh ruled over the Magonsaete; in later centuries it was said that Merewalh was a son of Penda, but this is considered uncertain. Stenton, for example, considered it likely that Merewalh was a representative of a local dynasty that continued to rule under Mercian domination.[65]

Final campaign and the battle of the Winwaed

In 655,[1] Penda invaded Bernicia with a large army, reported to have been 30 warbands, with 30 royal or noble commanders (duces regii, as Bede called them), including rulers such as Cadafael ap Cynfeddw of Gwynedd and Aethelhere of East Anglia. Penda also enjoyed the support of Aethelwald, the king of Deira and the successor of Oswine, who had been murdered on Oswiu's orders in 651.[66]

The cause of this war is uncertain. There is a passage in Bede's Ecclesiastical History that suggests Aethelhere of East Anglia was the cause of the war. On the other hand, it has been argued that an issue of punctuation in later manuscripts confused Bede's meaning on this point, and that he in fact meant to refer to Penda as being responsible for the war.[67] Although, according to Bede, Penda tolerated some Christian preaching in Mercia, it has been suggested that he perceived Bernician sponsorship of Christianity in Mercia and Middle Anglia as a form of "religious colonialism" that undermined his power, and that this may have provoked the war.[68] Elsewhere the possibility has been suggested that Penda sought to prevent Oswiu from reunifying Northumbria,[46] not wanting Oswiu to restore the kingdom to the power it had enjoyed under Edwin and Oswald. A perception of the conflict in terms of the political situation between Bernicia and Deira could help to explain the role of Aethelwald of Deira in the war, since Aethelwald was the son of Oswald and might not ordinarily be expected to ally with those who had killed his father. Perhaps, as the son of Oswald, he sought to obtain the Bernician kingship for himself.[68]

According to the Historia Brittonum, Penda besieged Oswiu at Iudeu;[25] this site has been identified with Stirling, in the north of Oswiu's kingdom.[69] Oswiu tried to buy peace: in the Historia Brittonum, it is said that Oswiu offered treasure, which Penda distributed among his British allies.[25] Bede states that the offer was simply rejected by Penda, who "resolved to extirpate all of [Oswiu's] nation, from the highest to the lowest". Additionally, according to Bede, Oswiu's son Ecgfrith was being held hostage "at the court of Queen Cynwise, in the province of the Mercians"[70]—perhaps surrendered by Oswiu as part of some negotiations or arrangement. It would seem that Penda's army then moved back south, perhaps returning home,[71] but a great battle was fought near the river Winwaed in the region of Loidis, thought to be somewhere in the area around modern day Leeds, on a date given by Bede as 15 November. The identification of the Winwaed with a modern river is uncertain, but possibly it was a tributary of the Humber. There is good reason to believe it may well have been the river now known as Cock Beck in the ancient kingdom of Elmet. The Cock Beck meanders its way through Pendas Fields, close to an ancient well known as Pen Well on the outskirts of Leeds, before eventually joining the River Wharfe. This same Cock Beck whilst in flood also played a significant role in the much later Battle of Towton in 1461. Another possibility is the River Went (a tributary of the River Don, situated to the north of modern-day Doncaster). It may be that Penda's army was attacked by Oswiu at a point of strategic vulnerability, which would help explain Oswiu's victory over forces that were, according to Bede, much larger than his own.[72]

The Mercian force was also weakened by desertions. According to the Historia Brittonum, Cadafael of Gwynedd, "rising up in the night, escaped together with his army" (thus earning him the name Cadomedd, or "battle-shirker"),[25] and Bede says that at the time of the battle, Aethelwald of Deira withdrew and "awaited the outcome from a place of safety".[70] According to Kirby, if Penda's army was marching home, it may have been for this reason that some of his allies were unwilling to fight. It may also be that the allies had different purposes in the war, and Kirby suggested that Penda's deserting allies may have been dissatisfied "with what had been achieved at Iudeu".[71] At a time when the Winwaed was swollen with heavy rains, the Mercians were badly defeated and Penda was killed, along with the East Anglian king Aethelhere. Bede says that Penda's "thirty commanders, and those who had come to his assistance were put to flight, and almost all of them slain," and that more drowned while fleeing than were killed in the actual battle. He also says that Penda's head was cut off; a connection between this and the treatment of Oswald's body at Maserfield is possible.[71] Writing in the 12th century, Henry of Huntingdon emphasised the idea that Penda was suffering the same fate as he had inflicted on others.[73]

Aftermath and historical appraisal

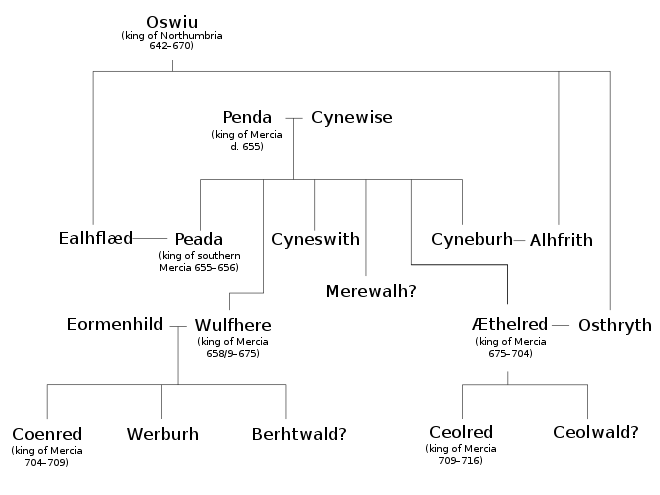

With the defeat at the Winwaed, Oswiu came to briefly dominate Mercia, permitting Penda's son Peada to rule its southern portion. Two of Penda's other sons, Wulfhere and Æthelred, later ruled Mercia in succession after the overthrow of Northumbrian control in the late 650s. The period of rule by Penda's descendants came to an end with his grandson Ceolred's death in 716, after which power passed to descendants of Eowa for most of the remainder of the 8th century.

Penda's reign is significant in that it marks an emergence from the obscurity of Mercia during the time of his predecessors, both in terms of the power of the Mercians relative to the surrounding peoples and in terms of our historical awareness of them. While our understanding of Penda's reign is quite unclear, and even the very notable and decisive battles he fought are surrounded by historical confusion, for the first time a general outline of important events regarding the Mercians becomes realistically possible. Furthermore, Penda was certainly of great importance to the development of the Mercian kingdom; it has been said that his reign was "crucial to the consolidation and expansion of Mercia".[36]

It has been claimed that the hostility of Bede has obscured Penda's importance as a ruler who wielded an imperium similar to that of other prominent 7th century 'overkings'. Penda's hegemony included lesser rulers of both Anglo-Saxon and British origins, non-Christian and Christian alike. The relationships between Penda, as hegemon, and his subordinate rulers would have been based on personal as well as political ties, and they would often have been reinforced by dynastic marriages. It has been asserted that Penda's court would have been cosmopolitan, multi-ethnic, multi-lingual and tolerant. Though a pagan himself, there is evidence that the contemporary Mercian elite contained significant Christian and British elements. Penda must have been intimate with many Britons and may have been bilingual himself.[74]

Penda was the last great pagan warrior-king among the Anglo-Saxons. Higham wrote that "his destruction sounded the death-knell of English paganism as a political ideology and public religion."[35] After Penda's death, the Mercians were converted to Christianity, and all three of Penda's reigning sons ruled as Christians. His daughters Cyneburh and Cyneswith became Christian and were saintly figures who according to some accounts retained their virginity through their marriages. There was purportedly even an infant grandson of Penda named Rumwold who lived a saintly three-day life of fervent preaching. What is known about Penda is primarily derived from the history written by the Northumbrian Bede, a priest not inclined to objectively portray a pagan Mercian who engaged in fierce conflict with Christian kings, and in particular with Northumbrian rulers. Indeed, Penda has been described as "the villain of Bede's third book" (of the Historia Ecclesiastica).[75] From the perspective of the Christians who later wrote about Penda, the important theme that dominates their descriptions is the religious context of his wars—for instance, the Historia Brittonum says that Penda prevailed at Maserfield through "diabolical agency"[26]—but Penda's greatest importance was perhaps in his opposition to the supremacy of the Northumbrians. According to Stenton, had it not been for Penda's resistance, "a loosely compacted kingdom of England under Northumbrian rule would probably have been established by the middle of the seventh century."[76] In summarising Penda, he wrote the following:

He was himself a great fighting king of the kind most honoured in Germanic saga; the lord of many princes, and the leader of a vast retinue attracted to his service by his success and generosity. Many stories must have been told about his dealings with other kings, but none of them have survived; his wars can only be described from the standpoint of his enemies ...[77]

Issue

Penda's wife is identified as Queen Cynewise or Kyneswitha.[70][78][79] He had five sons and two daughters:

- Peada, succeeded his father in 654 as King of Mercia, married Ealhflæd, daughter of King Oswiu[62][78][80]

- Wulfhere, King of Mercia 658–675; married Ermenilda of Ely[78][80]

- Æthelred, King of Mercia 675–704[78][80][81]

- Merewalh, King of the Magonsæte; married a daughter of King Eormenred of Kent[78][80]

- Mercelmus, sometimes mistranscribed as Mercelinus[78]

- Cyneburh, married Alhfrith, King of Deira, son of King Oswiu[78][80]

- Cyneswith, became a nun[78][80]

Portrayals

Penda appears in the historical novels King Penda's Captain (1908) by MacKenzie MacBride, The Soul of a Serf (1910) by J. Breckenridge Ellis, and Better Than Gold (2014) by Theresa Tomlinson.[82][83]

In the 1970s, Penda was depicted in two BBC television productions written by David Rudkin. He was played by Geoffrey Staines in Penda's Fen (1974),[84] and by Leo McKern in The Coming of the Cross (1975).[85]

On account of the association of his death with Leeds, the Pendas Fields estate in Leeds was named after Penda.[86]

Notes

- Manuscript A of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle gives the year as 655. Bede also gives the year as 655 and specifies a date, 15 November. R. L. Poole (Studies in Chronology and History, 1934) put forward the theory that Bede began his year in September, and consequently November 655 would actually fall in 654; Frank Stenton also dated events accordingly in his Anglo-Saxon England (1943).1 Others have accepted Bede's given dates as meaning what they appear to mean, considering Bede's year to have begun on 25 December or 1 January (see S. Wood, 1983: "Bede's Northumbrian dates again"). The historian D. P. Kirby suggested the year 656 as a possibility, alongside 655, in case the dates given by Bede are off by one year (see Kirby's "Bede and Northumbrian Chronology", 1963). The Annales Cambriae gives the year as 657. Annales Cambriae at Fordham University

- Bede gives the year of Hatfield as 633 (along with the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle); if the theory that Bede's years began in September is employed (see Note 1), then October 633 would actually be in 632, and this dating has sometimes been observed by modern historians such as Stenton (see Note 8). Kirby suggested that the year may have actually been 634, accounting for the possibility that Bede's dates are one year early (see Note 1). Bede gives the specific date of Hatfield as 12 October; Manuscript E of the Chronicle (see Note 10) gives it as 14 October.

- Damian Tyler, 'An Early Mercian Hegemony: Penda and Overkingship in the Seventh Century', Midland History, 30:1 (2005), 1–19 doi:10.1179/mdh.2005.30.1.1.

- Patrick Sims-Williams, Religion and Literature in Western England 600–800, Cambridge Studies in Anglo-Saxon England, 3 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 28.

- Graham Jones, 'Penda's footprint? Place-names containing personal names associated with those of early Mercian kings', Nomina, 21 (1998), 29–62.

- "Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England – Search".

- John Rhys, 1901 Celtic Folklore Welsh and Manx, Vol. II, Oxford University Press, p. 676

- P. Sims-Williams, Religion and Literature [in Western England, 600–800], Cambridge 1990, p. 26.

- Filppula et al., pp. 125–126.

- Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, 2006, ISBN 978-1851094400, p. 60

- Higham, Nicholas J.; Ryan, Martin J. (2013), The Anglo-Saxon World, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12534-4, p. 143 (for Pybba)

- Wade-Evans p. 325

- Notes and queries, Oxford Journals, 1920, p. 246.

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Manuscript A (ASC A), 626.2

- Historia Brittonum (HB), Chapter 60.3

- Kirby, The Earliest English Kings, page 57.4

- Williams, Ann, Kingship and Government in Pre-Conquest England, p. 29.

- Henry of Huntingdon, Historia Anglorum, Book II, 27.5

- Ziegler, "The Politics of Exile in Early Northumbria", note 39 Archived 16 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine.6

- Brooks, "The Formation of the Mercian Kingdom", page 165.7

- Kirby, page 67.4

- Kirby, page 68.4

- Brooks, page 166.7

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Book II, Chapter XX.8

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, page 81.1

- HB, Chapter 65.3

- Kirby was of the opinion that the battle "almost certainly" occurred a few years later than 628, but wrote that the battle "still reveals the wide-ranging character of Penda's early activities." (page 68)4

- Stenton, page 45.1

- ASC A, 628.2

- ASC A, 577.2

- Stenton argues (page 45) for the likelihood that the subkingdom of the Hwicce was Penda's creation;1 Bassett ("In search of the origins of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms", page 67) is more cautious, noting the lack of evidence.

- Brooks, page 167.7

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Manuscript E, 633.2

- Bede, B. II, Ch. XIV.8

- Higham, The Convert Kings, page 218–19.9 Higham accepts that Penda acknowledged Oswald's supremacy, but points to what he calls "the apparent failure of Bernician Christianity to penetrate the central Midlands" as evidence against assuming a great deal of authority exercised by Oswald over the Mercians during this period.

- Stancliffe, "Oswald, 'Most Holy and Most Victorious King of the Northumbrians'", in Oswald: Northumbrian King to European Saint, page 53.10 Stancliffe also has a favourable impression of Brooks' interpretation of Penda's position at this time (pages 55–56); see note 29.

- Kirby, page 74.4

- Kirby, page 77.4

- Stancliffe, "Oswald", page 54.10

- Bede, B. III, Ch. XVIII.7

- Kirby (Ch. 5, Note 26, page 207)4 explains some of the uncertainty surrounding the time of this battle: one source says that Anna died in the 19th year of his reign, in which case his reign would have begun around 635 and therefore the battle that killed his predecessor would also have been at about the same time; however, another source indicates that the ex-king Sigebert was still alive at least in 640 or 641.

- Kirby Earliest English Kings page 68

- Kirby Earliest English Kings pages 81–82

- Brooks, pages 165–67,7 argues against the idea that Penda and Eowa were co-rulers, and favours the idea that Eowa was ruling Mercia from c. 635 until 642.

- The date of Maserfield is subject to uncertainty similar to that which surrounds the dates of the battles of Hatfield Chase and the Winwaed. Manuscript A of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (see Note 1) gives the year as 642, as does Bede; however, if Hatfield actually occurred in 632 (see Note 2), then that would mean Maserfield occurred in 641. D. P. Kirby has suggested 643 as a possibility, allowing for Bede's chronology being one year early (see Note 1). The Annales Cambriae give the year as 644. Bede and the Chronicle (Manuscript E) agree that the date was 5 August.

- Brooks, page 168.7

- Stancliffe, page 56.10

- Tudor, "Reginald's Life of St Oswald", in Oswald: Northumbrian King to European Saint, page 185 (note 50).10 D. P. Kirby also considered Reginald's explanation of events, that Penda took refuge among the Welsh as Oswald advanced against him, as reasonable (page 74, and chapter 5, note 30).4

- Bede, B. III, Ch. XII.8

- Thacker, "Membra Disjecta: the Division of the Body and the Diffusion of the Cult", in Oswald: Northumbrian King to European Saint, page 97.10 Thacker says "perhaps as some form of sacrificial offering".

- David Rollason "Oswald" Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England London:Blackwell, 1999 pages 347–348

- Kirby Earliest English Kings page 77

- Kirby, page 54.4

- Stenton, page 83.1

- Kirby, page 48.4

- Bede (B. III, Ch. VII8) and the ASC agree that the exile was for three years; the ASC A says that it began in 645.

- Carver, "Kingship and material culture in early Anglo-Saxon East Anglia", page 155.7

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, ch. 5, "The northern Anglian hegemony", section 'The reign of Oswald'

- Kirby Earliest English Kings page 78

- Bede, B. III, Ch. XVI.7

- Bede, B. III, Ch. XVII.7

- Bede, B. III, Ch. XXI.7

- For an example of this interpretation, see Fisher, page 66.11

- Higham, page 232.9

- Stenton, page 47.1

- Kirby Earliest English Kings pages 78–81

- J. O. Prestwich12 cites the punctuation of an early version of Bede's history, the Leningrad manuscript (c. 746); he argues that it is more true to Bede's original meaning than the Moore manuscript (c. 737), which he believes was written in a hurried and careless fashion, but which has greatly influenced interpretations of the text.

- Higham, page 240.9

- Kirby, page 80.4

- Bede, B. III, Ch. XXIV.8

- Kirby, page 81.4

- Breeze, "The Battle of the Uinued and the River Went, Yorkshire", pages 381–82.13

- Henry of Huntingdon, The Chronicle of Henry of Huntingdon, translated by Thomas Forester (1853), page 59.

- Tyler, pp. 11, 14

- Prestwich, page 90.12

- Stenton, pages 81–82.1

- Stenton, page 39.1

- Florence of Worcester, Chronicon ex chronicis, p. 264: Identifies Cyneswitha as the wife of Penda and their five sons as Peada, Wulfhere, Æthelred, Merewald, and Mercelmus, and their two daughters as Cyneburgh and Cyneswitha.

- William of Malmesbury's Chronicle of the kings of England from the earliest period to the reign of King Stephen; p. 71; "Penda increased the number of infernal spirits. By his queen Kyneswith his sons were Peada, Wulfhere, Ethelred, Merwal, and Mercelin: his daughters, Kyneburg, and Kyneswith"

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Manuscript E, 656:2 Here Peada was killed; and Wulfhere, Penda's offspring, succeeded to the kingdom of the Mercians ... according to the advice of his brothers Æthelred and Merewala and according to the advice of his sisters Cyneburh and Cyneswith..."

- Bede (B. V, Ch. XXIV) states that in "675, Wulfhere, king of Mercia, died after a reign of seventeen years and left his kingdom to his brother Æthelred".

- Buckley, John Anthony and Williams, William Tom, A Guide to British Historical Fiction. G.G. Harrap: London, 1912. (pg. 14-5)

- "Review: Better Than Gold by Theresa Tomlinson" Review by Cassandra Clark. Historical Novel Society. February 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- "Penda's Fen (1974)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- "The Coming of the Cross (1975)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- James Rhodes, On this Day in Leeds ([no place]: rhodestothepast.com, 2019), p. 338 ISBN 978-0-244-17711-9.

References

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, translated and edited by M. J. Swanton (1996), paperback, ISBN 0-415-92129-5.

- S. Bassett (ed.), The Origins of Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms (1989).

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731), Book II and Book III.

- A. Breeze, "The Battle of the Uinued and the River Went, Yorkshire", Northern History, Vol. 41, Issue 2 (September 2004), pp. 377–383.

- Filppula, M., Klemola, J., Paulasto, H., and Pitkanen, H., (2008) English and Celtic in Contact, Routledge. ISBN 0-415-26602-5

- D. J. V. Fisher, The Anglo-Saxon Age (1973), Longman, hardback, ISBN 0-582-48277-1, pp. 66 & 117–118.

- Henry of Huntingdon, Historia Anglorum, translated by D. Greenway (1997), Oxford University Press.

- N. J. Higham, The Convert Kings: Power and Religious Affiliation in Early Anglo-Saxon England (1997), pp. 219, 240 & 241.

- The Historia Brittonum, Chapters 60 and 65.

- D. P. Kirby, The Earliest English Kings (1991), second edition (2000), Routledge, paperback, ISBN 0-415-24211-8.

- J. O. Prestwich, "King Æthelhere and the battle of the Winwaed," The English Historical Review, Vol. 83, No. 326 (January 1968), pp. 89–95.

- John Rhys, Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx (Oxford University Press 1901).

- P. Sims-Williams, Religion and Literature [in Western England, 600–800 (Cambridge 1990).

- C. Stancliffe and E. Cambridge (ed.), Oswald: Northumbrian King to European Saint (1995, reprinted 1996), Paul Watkins, paperback.

- F. M. Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England (1943), 3rd ed., (1971), Oxford University Press, paperback (1989, reissued 1998), ISBN 0-19-282237-3.

- Tyler, Damian (2005) "An Early Mercian Hegemony: Penda and Overkingship in the Seventh Century", in Midland History, Volume XXX, (ed. J. Rohrkasten). Published by the University of Birmingham.

- A. W. Wade-Evans, The Saxones in the "Excidium Britanniæ", The Celtic Review, Vol. 10, No. 40 (June 1916), pp. 322–333.

- Ann Williams, Kingship and Government in Pre-Conquest England (MacMillan Press 1999)

- M. Ziegler, "The Politics of Exile in Early Northumbria", The Heroic Age, Issue 2, Autumn/Winter 1999.