Ndumbe Lobe Bell

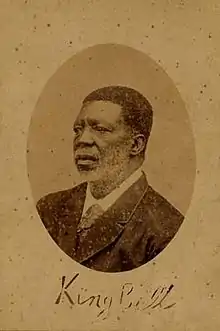

Ndumbé Lobé Bell or King Bell (1839 – December 1897[1]) was a leader of the Duala people in Southern Cameroon during the period when the Germans established their colony of Kamerun. He was an astute politician and a highly successful businessman.

| Ndumbé Lobé Bell | |

|---|---|

| Bell King of the Duala | |

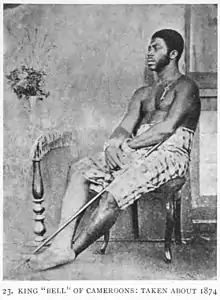

King Bell around 1874 | |

| Reign | 1858–97 |

| Predecessor | Lobe a Bebe |

| Successor | Manga Ndumbe Bell |

| Born | 1839 |

| Died | December 1897 |

Background

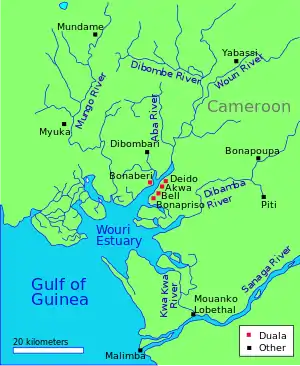

The first European records of the people of the Douala region around the Wouri estuary noted that they were engaged in fishing and agriculture to some extent, but primarily were traders with the people of the interior via the Wouri River and its tributaries, and via the Dibamba, Kwa Kwa and Mungo rivers.[2] The main Duala communities at the mouth of the Wouri River were Bell Town, with the subordinate Bonapriso to the south and Bonaberi in the opposite shore of the river, and Akwa Town with the subordinate Deido to the north.[3]

Douala was a dependable if minor source of slaves for the Atlantic Slave Trade.[4] The British became active in suppressing the trade in the 1820s. In November 1829 the British ship "Eden" seized the Brazilian slave trader "Ismenia" of Rio de Janeiro after it had given its trade goods to the then King Bell for the purpose of obtaining slaves.[5] On 7 March 1841, King Bell's predecessor signed a formal treaty with William Simpson Blount, commanding the British ship Pluto, in which he agreed to suppress the sale or transport of slaves in his territory.[6]

With the abolition of slavery, the Duala people expanded their barter trade in palm oil, palm kernels and ivory from the interior in exchange for European goods.[2] The practice of domestic slavery continued long after abolition of the overseas slave trade. Slaves were not necessarily mistreated. For example, David Mandessi Bell was brought as a slave from the Grassfields region into King Bell's household in the 1870s and became a rich and powerful member of the Bells, although he was not eligible to become chief.[4]

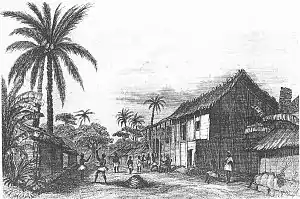

An 1880 guide said the towns of King Bell and King Aqua, "separated only by a little brook, are apparently of great extent and considerable population. The houses are neatly built of bamboo, in wide and regular streets, with numerous plantain and cocoa-nut trees, and even large fields of maize... A considerable trade has been carried on for many years with the natives, who from their activity in collecting palm oil, and their intercourse with Europeans, have become a large and important community, possessing a high degree of civilization".[7]

Independent rule

The Duala leaders, whom the Europeans called "kings", came from the two lineages of Bell and Akwa.[2] In practice, both Bell and Akwa suffered from internal divisions and did not have strong control over their subordinate communities, who rivalled them in trade and at times took independent action.[8] King Ndumbé Lobé Bell succeeded his father Lobé Bebe Bell in 1858, when he was aged about twenty. He was to lead the Bell faction for almost forty years until his death in 1897.[9]

Between 1872 and 1874 there was a conflict between the Akwa and Bell factions over an attempt by Bonapriso to secede to Akwa. King Bell was supported by Deido, which had become independent of Akwa, in this struggle.[8] In the late 1870s, King Bell managed to exploit a quarrel between the Akwa faction and the Kwa Kwa River traders to begin trading on this river, which leads to the much larger Sanaga River.[3] Between 1882 and 1883, just before the German annexation, a violent dispute broke out between King Bell and three of his brothers, supported by Akwa and Bonaberi.[8] These struggles were all harmful to the Bell trade.[10]

German assumption of control

By the later part of the 19th century the British were active in the Wouri estuary both as traders and missionaries and outnumbered the Germans, but accepted that the region fell within the German sphere of colonial authority.[11] King Bell sought European protection to support his authority, prevent further attempts to defect by segments of his people such as the Bonaberi, and stabilise trade.[11]

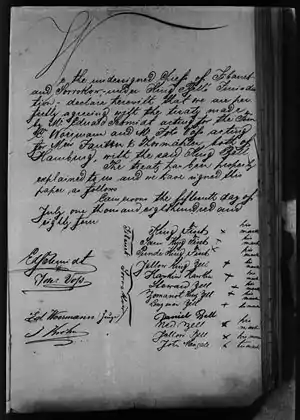

On 12 July 1884, King Ndumbé Lobé Bell and King Akwa signed a treaty in which they assigned sovereign rights, legislation and administration of their country in full to the firms of C. Woerman and Jantzen & Thormählen, represented by the merchants Edward Schmidt and Johann Voss.[12] The treaty included conditions that existing contracts and property rights be maintained, existing customs respected and the German administration continue to make "comey", or trading tax, payments to the kings as before. King Bell received 27,000 marks in exchange for signing the treaty, a very large sum at that time.[9]

In a letter to the Earl of Derby dated 30 September 1884, King Bell explained his reasons for accepting the German offer. He said "Having written to you, through the English Consuls on the West Coast, several times, covering the space of over five years, in which letters I anxiously inquired to know if the English Government would take by annexation my country, I at last despaired, having not received any answer… I hence concluded that neither the Consuls nor yet the English Government cared anything about my country…"[13]

The rulers of Bonaberi and Bonapriso refused to sign the German protectorate treaty in July 1884.[11] King Bell told the British Vice-Consul, Buchan, that the sub-chiefs would prefer British rule, but were waiting to see what the Germans would offer.[14] In December 1884, the forces of Bonaberi and Bonapriso attacked and burned Bell Town. Newspaper reports said that English traders had incited the sub-chiefs of Joss Town (Bonapriso) and Hickory Town (Bonaberi) against King Bell, saying he had failed to pass on their fair share of the money he was given by the Germans.[15] The German representative, Max Buchner, called on a small naval squadron to restore the peace, which they did by destroying both Bonaberi and Bonapriso. 25 Africans and one German died during the fighting. The Admiral of the naval squadron assumed authority until the first Governor, Julius von Soden, arrived in July 1885.[11]

German protectorate

King Bell's relations with the first Governor were poor. This was in part because of complaints to the central authorities by his nephew Alfred Bell, who was being educated in Germany.[10] Also, von Soden was committed to eliminating Bell dominance of the trade in the Mungo valley to the northwest of Douala, assisting the firm of Jantzen and Thormählen to expand into this region to start plantations and establish a trading station.[16] King Bell's English-educated son, Manga, was even exiled to Togo for two years, where he became friendly with the German commissioner Eugen von Zimmerer.[10]

Relations improved when von Zimmerer replaced von Soden as governor of the Kamerun colony in 1890.[10] Manga took care to cultivate the friendship of all the senior German officials in Douala, which helped in gaining support the Bell interests, while the Akwa leader failed to gain effective supporters among the colonialists.[16] Under Zimmerer, the Germans abandoned attempts to enter the principal Bell trading region in the Mungo River valley and turned instead to the Sanaga, which they closed to all native traders, further damaging Akwa interests.[17]

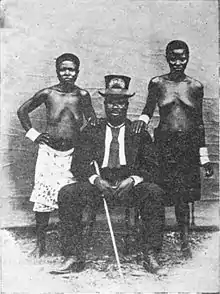

Character

Europeans who described the situation at Douala during the period before and after the formal colonial annexation praised King Bell and his son and heir, Manga, while they thought little of his rival, King Dika Mpondo Akwa.[10] King Bell was described as a man of natural dignity and decency.[9] Although there were more people in the Akwa faction, the Bells were more successful commercially and received higher payments than the Akwas after annexation.[10] King Bell had managed to eliminate the middlemen in the Mungo trade, greatly increasing his profits.[15]

Despite his astute and highly successful commercial and political dealings during a period of social upheaval, King Bell was the target of racist prejudices common among Europeans of that time. A typical verse in a German paper ran:[9]

- King Akwa and King Bell

Said lately: "Very well"

They took six measures of rum

And gave their whole kingdom.

When King Ndumbé Lobé Bell died in December 1897, he was said to have left 90 wives.[18] His son Manga Ndumbe Bell inherited his position and salary, and a few months later was given appeals jurisdiction over all non-Duala peoples of the Littoral, a highly lucrative appointment.[17]

Front view of the King Bells' Palace

Front view of the King Bells' Palace King Bell,s Monument

King Bell,s Monument

References

- Kamé 2008, pp. 418.

- Austen & Derrick 1999, pp. 6.

- Austen & Derrick 1999, pp. 84.

- Miers & Klein 1999, pp. 134–5.

- House of Commons 1831.

- Cochin 1863, pp. 239.

- Africa pilot, pp. 328–9.

- Austen & Derrick 1999, pp. 86.

- Pollack, Marcus & Westhoff 1886.

- Fowler & Zeitlyn 1996, pp. 74.

- Fowler & Zeitlyn 1996, pp. 66.

- von Joeden-Forgey 2002, pp. 59.

- Das Staatsarchiv 1885, pp. 315.

- Das Staatsarchiv 1885, pp. 66.

- Disturbances in the Cameroons.

- Austen & Derrick 1999, pp. 104.

- Austen & Derrick 1999, pp. 105.

- Bureau 1996, pp. 150.

Cited books

- Africa pilot, Part 1. Great Britain Hydrographic Dept. 1880.

- Austen, Ralph A; Derrick, Jonathan (1999). Middlemen of the Cameroons Rivers: the Duala and their hinterland, c. 1600–c. 1960. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56664-9.

- Bureau, René (1996). Le peuple du fleuve : sociologie de la conversion chez les Douala (in French). Karthala Editions. ISBN 2-86537-631-1.

- Cochin, Augustin (1863). Results of slavery. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 0-8369-5228-6.

- Das Staatsarchiv: Sammlung der offiziellen Aktenstücke zur Aussenpolitik der Gegenwart, volumes 44–5 (in German). Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft. 1885.

- "The Disturbances in the Cameroons". American annual cyclopaedia and register of important events. Vol. 25. D. Appleton and company. 1886. p. 121.

- Fowler, Ian; Zeitlyn, David (1996). African crossroads: intersections between history and anthropology in Cameroon. Berghahn Books. ISBN 1-57181-859-6.

- House of Commons papers. Vol. 19. HMSO. Great Britain Parliament House of Commons. 1831.

- Kamé, Bouopda Pierre (2008). Cameroun, du protectorat vers la démocratie, 1884–1992 (in French). Editions L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-05445-5.

- Miers, Suzanne; Klein, Martin A. (1999). Slavery and colonial rule in Africa. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-4436-6.

- Pollack, Wilhelm; Marcus, Eli; Westhoff, Friedrich (1886). King Bell oder die Münsteraner in Afrika (in German). Münster: Plattdeutsches Fastnachtspiel.

- von Joeden-Forgey, Elisa (2002). Mpundu Akwa: the case of the Prince from Cameroon; the newly discovered speech for the defense by Dr M Levi. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 3-8258-7354-4.