Edward V of England

Edward V (2 November 1470 – c. mid-1483)[1][2] was King of England from 9 April to 25 June 1483. He succeeded his father, Edward IV, upon the latter's death. Edward V was never crowned, and his brief reign was dominated by the influence of his uncle and Lord Protector, the Duke of Gloucester, who deposed him to reign as King Richard III; this was confirmed by the Act entitled Titulus Regius, which denounced any further claims through his father's heirs.

| Edward V | |

|---|---|

Depiction of Edward as Prince of Wales in the Dictes and Sayings of the Philosophers, 1477 | |

| King of England | |

| Reign | 9 April 1483 – 25 June 1483[1] |

| Predecessor | Edward IV |

| Successor | Richard III |

| Lord Protector | Richard, Duke of Gloucester |

| Born | 2 November 1470 Westminster, London, England |

| Died | c. mid-1483 (aged 12) |

| House | York |

| Father | Edward IV of England |

| Mother | Elizabeth Woodville |

| Signature |  |

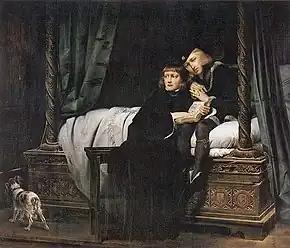

Edward V and his younger brother Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York, were the Princes in the Tower who disappeared after being sent to heavily guarded royal lodgings in the Tower of London. Responsibility for their deaths is widely attributed to Richard III, but the lack of solid evidence and conflicting contemporary accounts allow for other possibilities.

Early life

Edward was born on 2 November 1470 at Cheyneygates, the medieval house of the Abbot of Westminster, adjoining Westminster Abbey. His mother, Elizabeth Woodville, had sought sanctuary there from Lancastrian supporters who had deposed his father, the Yorkist king Edward IV, during the course of the Wars of the Roses. Edward was created Prince of Wales in June 1471,[1] following his father's restoration to the throne, and in 1473 was established at Ludlow Castle on the Welsh Marches as nominal president of a newly created Council of Wales and the Marches. In 1479, his father conferred the earldom of Pembroke on him; it became merged into the crown on his succession.[3]

Prince Edward was placed under the supervision of the queen's brother Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers, a noted scholar. In a letter to Rivers, Edward IV set down precise conditions for the upbringing of his son and the management of the prince's household.[4] He was to "arise every morning at a convenient hour, according to his age". His day would begin with matins and then Mass, which he was to receive uninterrupted. After breakfast, the business of educating the prince began with "virtuous learning". Dinner was served from ten in the morning, and then he was to be read "noble stories ... of virtue, honour, cunning, wisdom, and of deeds of worship" but "of nothing that should move or stir him to vice". Perhaps aware of his own vices, the king was keen to safeguard his son's morals, and instructed Rivers to ensure that no one in the prince's household was a habitual "swearer, brawler, backbiter, common hazarder, adulterer, [or user of] words of ribaldry". After further study, in the afternoon the prince was to engage in sporting activities suitable for his class, before evensong. Supper was served from four, and curtains were to be drawn at eight. Following this, the prince's attendants were to "enforce themselves to make him merry and joyous towards his bed". They would then watch over him as he slept.

Dominic Mancini reported of the young Edward V:

In word and deed he gave so many proofs of his liberal education, of polite nay rather scholarly, attainments far beyond his age; ... his special knowledge of literature ... enabled him to discourse elegantly, to understand fully, and to declaim most excellently from any work whether in verse or prose that came into his hands, unless it were from the more abstruse authors. He had such dignity in his whole person, and in his face such charm, that however much they might gaze, he never wearied the eyes of beholders.[5]

As with several of his other children, Edward IV planned a prestigious European marriage for his eldest son, and in 1480 concluded an alliance with Francis II, Duke of Brittany, whereby Prince Edward was betrothed to the duke's four-year-old daughter and heiress to the duchy, Anne. The two were to be married upon their majority, with their eldest son inheriting England and their second son Brittany.

Reign

It was at Ludlow that the 12-year-old Edward received news, on Monday 14 April 1483, of his father's sudden death five days before. Edward IV's will, which has not survived, nominated his trusted brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, as Protector during the minority of his son. The new king left Ludlow on 24 April, with Richard leaving York a day earlier, planning to meet at Northampton and travel to London together. However, when Richard reached Northampton, Edward and his party had already travelled onward to Stony Stratford, Buckinghamshire.[7] The Earl Rivers travelled back to Northampton to meet Richard and Buckingham, who had now arrived. On the night of 29 April Richard dined with Rivers and Edward's half-brother, Richard Grey, but the following morning Rivers, Grey and the king's chamberlain, Thomas Vaughan, were arrested and sent north.[8] Despite Richard's assurances, all three were subsequently executed. Dominic Mancini, an Italian who visited England in the 1480s, reports that Edward protested, but the remainder of his entourage was dismissed and Richard escorted him to London. On 19 May 1483, the new king took up residence in the Tower of London; on 16 June, his younger brother Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York joined him there.[9]

The council had originally hoped for an immediate coronation to avoid the need for a protectorate. This had previously happened with Richard II, who had become king at the age of ten. Another precedent was Henry VI, whose protectorate (which started when he inherited the crown aged 9 months) had ended with his coronation aged seven. Richard, however, repeatedly postponed the coronation.[10]

On 22 June, Ralph Shaa preached a sermon declaring that Edward IV had already been contracted to marry Lady Eleanor Butler when he married Elizabeth Woodville, thereby rendering his marriage to Elizabeth invalid and their children together illegitimate.[10] The children of Richard's older brother George, Duke of Clarence, were barred from the throne by their father's attainder, and therefore, on 25 June, an assembly of Lords and Commons declared Richard to be the legitimate king (this was later confirmed by the act of parliament Titulus Regius). The following day he acceded to the throne as King Richard III.

Disappearance

Dominic Mancini recorded that after Richard III seized the throne, Edward and his brother Richard were taken into the "inner apartments of the Tower" and then were seen less and less until the end of the summer to the autumn of 1483, when they disappeared from public view altogether. During this period Mancini records that Edward was regularly visited by a doctor, who reported that Edward, "like a victim prepared for sacrifice, sought remission of his sins by daily confession and penance, because he believed that death was facing him."[11] The Latin reference to Argentinus medicus had previously been translated as "a doctor from Strasbourg", because the Latin name for the city of Strasbourg, Argentoratum, was still current at the time; however, D. E. Rhodes suggests it may actually refer to "Doctor Argentine", whom Rhodes identifies as John Argentine, an English physician who would later serve as provost of King's College, Cambridge, and as doctor to Arthur, Prince of Wales, eldest son of King Henry VII of England (Henry Tudor).[9]

The princes' fate after their disappearance remains unknown, but the most widely accepted theory is that they were murdered on the orders of their uncle, King Richard.[12] Thomas More wrote that they were smothered to death with their pillows, and his account forms the basis of William Shakespeare's play Richard III, in which Tyrrell murders the princes on Richard's orders. In the absence of hard evidence a number of other theories have been put forward, of which the most widely discussed are that they were murdered on the orders of Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, or by Henry Tudor. However, A. J. Pollard points out that these theories are less plausible than the straightforward one that they were murdered by their uncle[13] who in any case controlled access to them and was therefore regarded as responsible for their welfare.[14] In the period before the boys' disappearance, Edward was regularly being visited by a doctor; historian David Baldwin extrapolates that contemporaries may have believed Edward had died of an illness (or as the result of attempts to cure him).[15] An alternative theory is that Perkin Warbeck, a pretender to the throne, was indeed Richard, Duke of York, as he claimed, having escaped to Flanders after his uncle's defeat at Bosworth to be raised by his aunt, Margaret, Duchess of Burgundy.

In 2021, researchers from "The Missing Princes Project"[16] claimed to have found evidence that Edward may have lived out his days in the rural Devon village of Coldridge. They have linked the 13-year-old prince with a man named John Evans, who arrived in the village around 1484, and was immediately given an official position and the title of Lord of the Manor.[17] Researcher John Dike noted Yorkist symbols and stained glass windows depicting Edward V in a Coldridge chapel commissioned by Evans and built around 1511, unusual for the location [18]

Bones belonging to two children were discovered in 1674 by workmen rebuilding a stairway in the Tower. On the orders of King Charles II, these were subsequently placed in Westminster Abbey, in an urn bearing the names of Edward and Richard.[19] The bones were re-examined in 1933, at which time it was discovered the skeletons were incomplete and had been interred with animal bones. It has never been proven that the bones belonged to the princes, and it is possible that they were buried before the reconstruction of that part of the Tower of London.[20] Permission for a subsequent examination has been refused.

In 1789, workmen carrying out repairs in St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, rediscovered and accidentally broke into the vault of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. Adjoining this was another vault, which was found to contain the coffins of two children. This tomb was inscribed with the names of two of Edward IV's children who had predeceased him: George, Duke of Bedford, and Mary. However, the remains of these two children were later found elsewhere in the chapel, leaving the occupants of the children's coffins within the tomb unknown.[21]

In 1486 Edward IV's daughter Elizabeth, sister of Edward V, married Henry VII, thereby uniting the Houses of York and Lancaster.

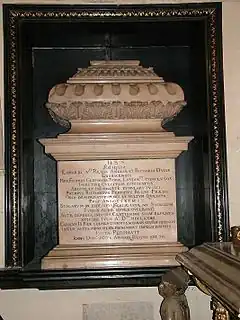

Epitaph

As outlined above, on the orders of Charles II, the presumed bones of Edward V and his brother Richard were interred in Westminster Abbey; Edward was thus buried in the place of his birth. The white marble sarcophagus was designed by Sir Christopher Wren and made by Joshua Marshall. The sarcophagus can be found in the north aisle of the Henry VII Chapel, near Elizabeth I's tomb.

The Latin inscription on the urn can be translated as follows:

Here lie the relics of Edward V, King of England, and Richard, Duke of York. These brothers being confined in the Tower of London, and there stifled with pillows, were privately and meanly buried, by the order of their perfidious uncle Richard the Usurper; their bones, long enquired after and wished for, after 191 years in the rubbish of the stairs (those lately leading to the Chapel of the White Tower) were on the 17th day of July AD 1674 by undoubted proofs discovered, being buried deep in that place. Charles II, a most compassionate king, pitying their severe fate, ordered these unhappy princes to be laid amongst the monuments of their predecessors, AD 1678, in the 30th year of his reign.[22]

The original Latin text is as follows (original all in capitals):[23]

H.SS Reliquiæ Edwardi Vti Regis Angliæ et Richardi Ducis Eboracensis

Hos, fratres germanos, Turre Londinˢⁱ conclusos iniectisq culcitris suffocatos, abdite et inhoneste tumulari iussit patruus Richardus Perfidus Regni prædo ossa desideratorum, div et multum quæsita, post annos CXC&1~ scalarum in ruderibus (scala istæ ad Sacellum Turris Albæ nuper ducebant) alte defossa, indictis certissimis sunt reperta XVII die iulii Aº Dⁿⁱ MDCLXXIIII

Carolus II Rex clementissimu sacerbam sortem miseratus inter avita monumena principibus infelicissimis. iusta persolvit. anno domⁱ 1678 annoq regni sui 30

Genealogy

| English royal families in the Wars of the Roses |

|---|

|

Dukes (except Aquitaine) and Princes of Wales are noted, as are the monarchs' reigns.

Individuals with red dashed borders are Lancastrians and blue dotted borders are Yorkists. Some changed sides and are represented with a solid thin purple border. Monarchs have a rounded-corner border. See also Family tree of English monarchs |

Portrayals in fiction

Edward appears as a character in the play Richard III by William Shakespeare. Edward appears alive in only one scene of the play (Act 3 Scene 1), during which he and his brother are portrayed as bright, precocious children who see through their uncle's ambitions. Edward in particular is portrayed as wiser than his years (something his uncle notes) and ambitious about his kingship. Edward and his brother's deaths are described in the play, but occur offstage. Their ghosts return in one more scene (Act 5 Scene 3) to haunt their uncle's dreams and promise success to his rival, Richmond (i.e. King Henry VII). In film and television adaptations of this play, Edward V has been portrayed by the following actors:

- Kathleen Yorke in the 1911 silent short dramatising a part of the play.

- Howard Stuart in the 1912 silent adaptation.

- Paul Huson in the 1955 film version, alongside Laurence Olivier as Richard.

- Hugh Janes in the 1960 BBC series An Age of Kings, which contained all the history plays from Richard II to Richard III.

- Nicolaus Haenel in the 1964 West German TV version König Richard III.

- Dorian Ford in the 1983 BBC Shakespeare version.

- Spike Hood provided his voice in the 1994 BBC series Shakespeare: The Animated Tales.

- Marco Williamson in the 1995 film version, alongside Ian McKellen as Richard.

- Jon Plummer in the 2005 modernised TV version set on a Brighton housing estate.

- Germaine De Leon in the 2007 modern-day adaptation.

- Edward Bracey in the 2014 drama documentary Richard III: The Princes in the Tower.

- Caspar Morley played Edward in the BBC's 2016 adaptation of Shakespeare's Richard III alongside Benedict Cumberbatch as Richard. It is the final episode in the second season of The Hollow Crown.

Edward V is also featured as a mute role in another of Shakespeare's plays, Henry VI, Part 3, where he appears as a newborn baby in the final scene. His father Edward IV addresses his own brothers thus: "Clarence, and Gloster, [sic] love my lovely queen, And kiss your princely nephew, brothers both." Gloster, the future Richard III, is at the close of this play already encompassing his nephew's demise, as he mutters in an aside, "To say the truth, so Judas kiss'd his master, And cried – All hail! when as he meant – all harm."[24]

Edward appears in The White Queen, a 2009 historical novel by Philippa Gregory and in the subsequent 2013 TV miniseries The White Queen; in the latter, he is played by Sonny Ashbourne Serkis.[25][26]

Heraldry

As heir apparent, Edward bore the royal arms (quarterly France and England) differenced by a label of three points argent. During his brief reign, he used the royal arms undifferenced, supported by a lion and a hart as had his father.[27] His livery badges were the traditional Yorkist symbols of the fetterlocked falcon and the rose argent.[28]

.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms as heir apparent (1471–1483)

Coat of arms as heir apparent (1471–1483).svg.png.webp) Coat of arms as King Edward V (1483)

Coat of arms as King Edward V (1483) Falcon and fetterlock

Falcon and fetterlock White rose of York

White rose of York

See also

Sources

References

- Alison, Weir (2008). Britain's Royal Family: the Complete Genealogy. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-0995-3973-5.

- Walker, R. F. (1963). "Princes in the Tower". In Steinberg, S. H.; et al. (eds.). A New Dictionary of British History (1963 ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 286. OCLC 398024. OL 5886803M.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 79.

- Letter from Edward IV to Earl Rivers and the Bishop of Rochester (1473), in Readings in English Social History (Cambridge University Press, 1921), pp. 205–8.

- Dominic Mancini, The Usurpation of Richard III (1483), in A. R. Myers (ed.), English Historical Documents 1327–1485 (Routledge, 1996), pp. 330–3.

- "King Edward V – National Portrait Gallery". npg.org.uk. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- 'Parishes : Stony Stratford', Victoria History of the Counties of England, A History of the County of Buckingham: Volume 4 (1927), pp. 476–482. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- "History of Croyland Abbey, Third Continuation". R3.org. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Rhodes, D. E. (April 1962). "The Princes in the Tower and Their Doctor". The English Historical Review. Oxford University Press. 77 (303): 304–306. doi:10.1093/ehr/lxxvii.ccciii.304.

- Pollard (1991).

- "The Usurpation of Richard the Third", Dominicus Mancinus ad Angelum Catonem de occupatione regni Anglie per Riccardum Tercium libellus; Translated to English by C. A. J. Armstrong (London, 1936)

- Horrox, Rosemary. "Edward V of England". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 25 August 2013. (subscription required)

- Pollard (1991), pp. 124, 132.

- Pollard (1991), p. 137.

- David Baldwin, What happened to the Princes in the Tower?, BBC History: 2013

- Langley, Philippa. "The Missing Princes Project". Retrieved 7 November 2022 https://revealingrichardiii.com/langley.html

- https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/richard-iii-didnt-murder-princes-25809860 Daily Mirror newspaper (UK) - 29 Dec 2021

- https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2021/12/28/richard-iii-may-not-have-killed-young-princes-tower-london-new/ Gardner, Bill (28 December 2021). "Exclusive: Richard III may not have killed young princes in the Tower of London, researchers say". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- Steane, John, The Archaeology of the Medieval English Monarchy (Routledge, 1993), p. 65

- Weir (1992).

- 1. Chapter Records XXIII to XXVI, The Chapter Library, St. George's Chapel, Windsor (Permission required) 2. William St. John Hope, Windsor Castle: An Architectural History, pages 418–419. (1913). 3. Vetusta Monumenta, Volume III, page 4 (1789).

- westminster-abbey.org

- Google Images

- Henry VI, Part 3, Act 5, Scene VII, Lines 26–27, 33–34.

- "The White Queen". Publishers Weekly. 29 June 2009. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- "The White Queen Cast". tvgeek. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- Charles Boutell (1864). Heraldry, Historical and Popular, Volume 1.

- Burke, John; Burke, Bernard (1842). A General Armory of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

Works cited

- Pollard, A. J. (1991). Richard III and the Princes in the Tower. Alan Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-8629-9660-0.

- Weir, Alison (1992). The Princes in the Tower. The Bodley Head. ISBN 0-3703-1792-0.

Further reading

- Ashley, Mike (2002). British Kings & Queens. Carroll & Graf. pp. 217–219. ISBN 0-7867-1104-3. OL 8141172M.

- Hicks, Michael (2003). Edward V: The Prince in the Tower. The History Press. ISBN 0-7524-1996-X.

- Kendall, Paul Murray (1955). Richard III. W. W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-3930-0785-5. OL 7450809M.

- Daily Telegraph, 28th December 2021, page 3. "Richard III may not have killed young princes in the Tower of London, researchers say".

External links

- Edward V at the official website of the British monarchy

- Edward V at BBC History

- Who were the Missing Princes The Missing Princes Project - Philippa Langley

- Portraits of King Edward V at the National Portrait Gallery, London