Christian V of Denmark

Christian V (15 April 1646 – 25 August 1699) was King of Denmark and Norway from 1670 until his death in 1699.[1]

| Christian V | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Jacob d'Agar, c. 1685. The king poses with his hand authoritatively placed on the marshal's baton, as a true absolute monarch. | |

| King of Denmark and Norway | |

| Reign | 9 February 1670 – 25 August 1699 |

| Coronation | 7 June 1671 Frederiksborg Palace Chapel |

| Predecessor | Frederick III |

| Successor | Frederick IV |

| Grand Chancellors | See list |

| Born | 15 April 1646 Duborg Castle, Flensburg |

| Died | 25 August 1699 (aged 53) Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | |

| Issue among others... | Frederick IV of Denmark Prince Christian Princess Sophia Hedwig Prince Charles Prince William illegitimate: Christian Gyldenløve |

| House | Oldenburg |

| Father | Frederick III of Denmark |

| Mother | Sophie Amalie of Brunswick-Lüneburg |

| Religion | Lutheran |

| Danish Royalty |

| House of Oldenburg Main Line |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

| Christian V |

|

Well-regarded by the common people, he was the first king anointed at Frederiksborg Castle chapel as absolute monarch since the decree that institutionalized the supremacy of the king in Denmark-Norway. Christian fortified the absolutist system against the aristocracy by accelerating his father's practice of allowing both Holstein nobles and Danish and Norwegian commoners into state service.

As king, he wanted to show his power as absolute monarch through architecture, and dreamed of a Danish Versailles. He was the first to use the 1671 Throne Chair of Denmark, partly made for this purpose.[2] His motto was: Pietate et Justitia (With piety and justice).

Biography

Early years

Prince Christian was born on 15 April 1646 at Duborg Castle in the city of Flensburg, then located in the Duchy of Schleswig. He was the first legitimate child born to the then Prince Frederick of Denmark by his consort, Sophie Amalie of Brunswick-Calenberg. Prince Frederick was a younger son of King Christian IV, but the death of his elder brother Christian, Prince-Elect of Denmark in June 1647 opened the possibility for Frederick to be elected heir apparent to the Danish throne.

After the death of King Christian IV in 1648, Frederick thus became King of Denmark and Norway as Frederick III. Prince Christian was elected successor to his father in June 1650. This was not a free choice, but de facto automatic hereditary succession. Escorted by his chamberlain Christoffer Parsberg, Christian went on a long trip abroad, to Holland, England, France, and home through Germany. On this trip, he saw absolutism in its most splendid achievement at the young Louis XIV's court, and heard about the theory of the divine right of kings. He returned to Denmark in August 1663. From 1664 he was allowed to attend proceedings of the State College. Hereditary succession was made official by Royal Law in 1665. Christian was hailed as heir in Copenhagen in August 1665, in Odense and Viborg in September, and in Christiania, Norway in July 1666. Only a short time before he became king, he was taken into the Council of the Realm and the Supreme Court.

Accession

On 9 February 1670, King Frederick III died at the age of 60 at the Copenhagen Castle after a reign of 22 years. At the death of his father, Frederick immediately ascended the thrones of Denmark and Norway as the second absolute monarch at the age of just 24. He was formally crowned on 7 June the following year in the chapel of Frederiksborg Palace, which thereafter became the traditional place of coronation of Denmark's monarchs during the days of the absolute monarchy.[3] He was the first hereditary king of Denmark-Norway, and in honor of this, Denmark-Norway acquired costly new crown jewels and a magnificent new ceremonial sword.[4]

Reign

It is generally argued that Christian V's personal courage and affability made him popular among the common people, but his image was marred by his unsuccessful attempt to regain Scania for Denmark in the Scanian War. The war exhausted Denmark's economic resources without securing any gains.[5] Part of Christian's appeal to the common people may be explained by the fact that he allowed Danish and Norwegian commoners into state service, but his attempts to curtail the influence of the nobility also meant continuing his father's drive toward absolutism.[5][6] To accommodate non-aristocrats into state service, he created the new noble ranks of count and baron. One of the commoners elevated in this way by the king was Peder Schumacher, named Count of Griffenfeld by Christian V in 1670 and high councillor of Denmark in 1674.[5][7]

Griffenfeld, a skilled statesman, better understood the precarious situation Denmark-Norway placed itself by attacking Sweden at a time when the country was allied with France, the major European power of the era. After some hesitation, Christian V initiated the Scanian War (1675-1679) against Sweden in an attempt to reconquer Scania which Denmark had lost under the Treaty of Roskilde in 1658. As Griffenfeld predicted, Sweden's stronger ally France was the party that dictated the peace with Denmark's ally the Netherlands, and in spite of Danish victory at sea in the battles against Sweden in 1675–1679 during the Scanian War, Danish hopes for border changes on the Scandinavian Peninsula between the two countries were dashed. The results of the war efforts proved politically and financially unremunerative for Denmark-Norway. The damage to the Danish-Norwegian economy was extensive. At this point, Christian V no longer had his most experienced foreign relations counsel around to repair the political damage — in 1676 he had been persuaded to sacrifice Griffenfeld as a traitor, and to the clamour of his adversaries, Griffenfeld was imprisoned for the remainder of his life.[8]

.jpg.webp)

After the Scanian War, his sister, Princess Ulrike Eleonora of Denmark, married Swedish king Charles XI, whose mother was a stout supporter of the Duke of Holstein-Gottorp. In spite of the family ties, war between the brothers-in-law was close again in 1689, when Charles XI nearly provoked confrontation with Denmark-Norway by his support of the exiled Christian Albert, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp in his claims to Holstein-Gottorp in Schleswig-Holstein.[9]

Like Charles XI of Sweden, who had never been outside Sweden, Christian V spoke only German and Danish and was therefore often considered poorly educated due to his inability to communicate with visiting foreign diplomats.[9] Christian V was also often considered dependent on his councillors by contemporary sources. The Danish monarch did nothing to dispel this notion. In his memoirs, he listed "hunting, love-making, war and maritime affairs" as his main interests in life.[8]

Christian V introduced the Danish Code (Danske Lov) in 1683, the first law code for all of Denmark.[10] He also introduced the similar Norske Lov (Norwegian Code) of 1687 to replace Christian IVs Norwegian Code from 1604 in Norway. He also introduced the land register of 1688, which attempted to work out the land value of the united monarchy in order to create a more just taxation.

During the reign of Christian V, Denmark's trade in cattle that had declined due to catastrophic fires and wars had been restored, and livestock and crop exports had also surpassed Frederick III, with thousands of cattle entering and leaving Jutland through the Oxen Way. After entering and fattening in the Danish King's German enclave County of Oldenburg, the cattle reached the big market in Wedel. From there, cattle are resold to all parts of North Germany via Stade, Hamburg and Lübeck. As the population continues to soar at the end of the seventeenth century, demand for beef, grains and fish is increasing, both throughout North Germany and on the Baltic coast alone. In terms of the number of livestock shipped to the South, in 1680 each market had reached 40,000 cattle. Traditional export commodities, including fish and grains, have increased their exports since the beginning of the seventeenth century. The agricultural products exported by Denmark, especially cattle, have made a lot of money from Germany and the Netherlands for the Danish royal family, the aristocrats and the town residents. During his reign, science witnessed a golden age due to the work of the astronomer Ole Rømer in spite of the king's personal lack of scientific knowledge and interest. He died from the after-effects of a hunting accident and was interred in Roskilde Cathedral.[8][11]

Family

Christian V had eight children by his wife and six by his Maîtresse-en-titre, Sophie Amalie Moth (1654–1719), whom he took up with when she was sixteen. Sophie was the daughter of his former tutor Poul Moth. Christian publicly introduced Sophie into court in 1672, a move which insulted his wife, and made her countess of Samsø on 31 December 1677.

Legitimate children by his queen Charlotte Amalie:

| Name | Birth | Death |

|---|---|---|

| Frederick IV | 2 October 1671 | 12 October 1730 |

| Christian Vilhelm | 1 December 1672 | 25 January 1673 |

| Christian | 25 March 1675 | 27 June 1695 |

| Sophie Hedevig | 28 August 1677 | 13 March 1735 |

| Christiane Charlotte | 18 January 1679 | 24 August 1689 |

| Charles | 26 October 1680 | 8 June 1729 |

| Daughter | 17 July 1683 | 17 July 1683 |

| Vilhelm | 21 February 1687 | 23 November 1705 |

Illegitimate children by his mistress, Sophie Amalie Moth, Countess of Samsø:

| Name | Birth | Death |

|---|---|---|

| Christiane Gyldenløve | 7 July 1672 | 12 September 1689 |

| Christian Gyldenløve | 28 February 1674 | 16 July 1703 |

| Sophie Christiane Gyldenløve | 1675 | 18 August 1684 |

| Anna Christiane Gyldenløve | 1676 | 11 August 1689 |

| Ulrik Christian Gyldenløve | 24 June 1678 | 8 December 1719 |

| Daughter | 1682 | 8 July 1684 |

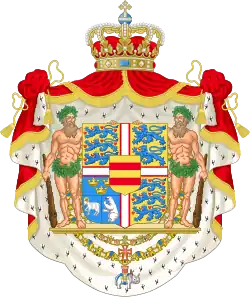

Arms

| Heraldry of Christian V of Denmark-Norway | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Christian V's crown, produced in 1671 | Royal Monogram | Coat of arms as King |

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Christian V of Denmark |

|---|

References

- "Christian V, 1646-99". Dansk biografisk Lexikon. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Written by the Frederiksborg's historian staff on the official website of the institution.

- Monrad Møller, Anders (2012). "Den første salving under enevælden" [The first anointing during the absolute monarchy]. Enevældens kroninger. Syv salvinger – ceremoniellet, teksterne og musikken [The coronations of the absolute monarchy. Seven anointings – the ceremonial, the lyrics and the music] (in Danish). København: Forlaget Falcon. pp. 28–57. ISBN 978-87-88802-29-0.

- Monrad Møller, Anders (2012). "Regalier, tronstole, løver og kåber" [Regalia, thrones, lions and robes]. Enevældens kroninger. Syv salvinger – ceremoniellet, teksterne og musikken [The coronations of the absolute monarchy. Seven anointings – the ceremonial, the lyrics and the music] (in Danish). København: Forlaget Falcon. pp. 17–24. ISBN 978-87-88802-29-0.

- "Christian V." (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 January 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Jespersen, Knud J.V. The Introduction of Absolutism Archived 11 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Gyldendal Leksikon, quoted by The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, on Denmark's official web site.

- "Peder Schumacher, Greve af Griffenfeld 1635-99". Dansk biografisk Lexikon. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Nielsen, Kay Søren (1999). Christian V – Konge og sportsmand Archived 25 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine. The Royal Danish Arsenal Museum, Net Publications, 1999.

- Upton, Anthony F. (1998). Charles XI and Swedish Absolutism, 1660–1697. Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-521-57390-4.

- Jespersen, Knud J.V. Denmark as a Modern Bureaucracy Archived 11 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Gyldendal Leksikon, quoted by The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, on Denmark's official web site.

- Knud J.V. Jespersen. "Christian 5". Den Store Danske, Gyldendal. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

External links

- The Royal Lineage at the website of the Danish Monarchy

- Christian V at the website of the Royal Danish Collection

- The Royal Orders of Chivalry (Order of Dannebrog, instituted by Christian V in 1671) — Official site of the Danish Monarchy

- Nielsen, Kay Søren. "Christian V. Konge og sportsmand" (in Danish). The Royal Danish Arsenal Museum. Archived from the original on 25 April 2007. Retrieved 29 November 2009.