Ahab

Ahab (Hebrew: אַחְאָב, Modern: ʾAḥʾav, Tiberian: ʾAḥʾāḇ; Akkadian: 𒀀𒄩𒀊𒁍 Aḫâbbu [a-ḫa-ab-bu]; Koinē Greek: Ἀχαάβ Achaáb; Latin: Achab) was the seventh king of Israel, the son and successor of King Omri and the husband of Jezebel of Sidon, according to the Hebrew Bible.[1] The Hebrew Bible presents Ahab as a wicked king, particularly for condoning Jezebel's influence on religious policies and his principal role behind Naboth's arbitrary execution.

| Ahab | |

|---|---|

| |

| King of Northern Israel | |

| Reign | c. 871 – c. 852 BC |

| Predecessor | Omri |

| Successor | Ahaziah |

| Died | c. 852 BC Ramoth-Gilead, Syria |

| Burial | |

| Consort | Jezebel of Sidon |

| Issue | |

| Dynasty | Omrides |

| Father | Omri |

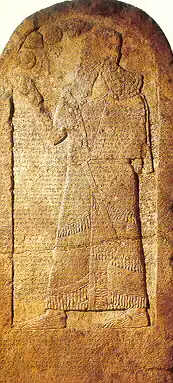

The existence of Ahab is historically supported outside the Bible. Shalmaneser III of Assyria documented in 853 BC that he defeated an alliance of a dozen kings in the Battle of Qarqar; one of these was Ahab. He is also mentioned on the inscriptions of the Mesha Stele.[2]

Ahab became king of Israel in the thirty-eighth year of King Asa of Judah, and reigned for twenty-two years, according to 1 Kings.[3] William F. Albright dated his reign to 869–850 BC, while Edwin R. Thiele offered the dates 874–853 BC.[4] Most recently, Michael Coogan has dated Ahab's reign to 871–852 BC.[5]

Reign

King Omri, Ahab's father and founder of the short-lived Omri dynasty, seems to have been a successful military leader; he is reported in the text of the Moabite Mesha Stele to have "oppressed Moab for many days." During Ahab's reign, Moab, which had been conquered by his father, remained tributary. Ahab was allied by marriage with Jehoshaphat, who was king of Judah. Only with Aram-Damascus is he believed to have had strained relations, though the two kingdoms also shared an alliance for some years.[6]

Ahab married Jezebel, the daughter of the King of Tyre. kings 16–22 1 Kings 16:1–22:53 tells the story of Ahab and Jezebel, and indicates that Jezebel was a dominant influence on Ahab, persuading him to abandon Yahweh and establish the religion of Baal in Israel.[lower-alpha 1] Ahab lived in Samaria, the royal capital established by Omri, and built a temple and altar to Baal there.[7] These actions were said to have led to severe consequences for Israel, including a drought that lasted for several years and Jezebel's fanatical religious persecution of the prophets of Yahweh, which Ahab condoned. His reputation was so negative that in 1 Kings 16:34, the author attributed to his reign the deaths of Abiram and Segub, the sons of Hiel of Bethel, caused by their father's invocation of Joshua's curse several centuries before.

According to 1 Kings 20, war later erupted between Ahab and king Hadadezer of Aram-Damascus (which the Bible refers to as "Ben-Hadad II") and that Ahab was able to defeat and capture him; however, soon after that, a peace treaty was made between the two and alliance between Israel and Aram-Damascus was formed.[6]

Battle of Qarqar

The Battle of Qarqar is mentioned in extra-biblical records, and was perhaps at Apamea, where Shalmaneser III of Assyria fought a great confederation of princes from Cilicia, Northern Syria, Israel, Ammon, and the tribes of the Syrian desert (853 BCE), including Arabs, Ahab the Israelite (A-ha-ab-bu matSir-'a-la-a-a)[8] and Hadadezer (Adad-'idri).[6]

Ahab's contribution was estimated at 2000 chariots and 10,000 men. In reality, however, the number of chariots in Ahab's forces was probably closer to a number in the hundreds (based upon archaeological excavations of the area and the foundations of stables that have been found).[9] If, however, the numbers are referring to allies, they could possibly include forces from Tyre, Judah, Edom, and Moab. The Assyrian king claimed a victory, but his immediate return and subsequent expeditions in 849 BC and 846 BC against a similar but unspecified coalition seem to show that he met with no lasting success.

Jezreel has been identified as Ahab's fortified chariot and cavalry base.[10]

Ahab and the prophets

In the Biblical text, Ahab has five important encounters with prophets:

- The first encounter is with Elijah, who predicts a drought because of Ahab's sins.[11] Because of this, Ahab refers to him as "the troubler of Israel" (1 Kings 18:17). This encounter ends with Elijah's victory over the prophets of Baal in a contest held for the sake of Ahab and the Israelites, to bring them into repentance.[12]

- The second encounter is between Ahab and an unnamed prophet in 1 Kings 20:22.

- The third is again between Ahab and an unnamed prophet who condemns Ahab for his actions in a battle that had just taken place.[13]

- The fourth is when Elijah confronts Ahab over his role in the unjust execution of Naboth and usurpation of the latter's ancestral vineyard.[14] Upon the prophet's remonstration ("Hast thou killed and also taken possession?"[15]), Ahab sincerely repented, which God relays to Elijah.[16]

- The fifth encounter is with Micaiah, the prophet who, when asked for advice to recapturing Ramoth-Gilead, sarcastically assures Ahab that he will be successful. Micaiah ultimately tells him the truth of God's plan to kill Ahab in battle, due to his reliance on the false prophets, who were empowered by a deceiving spirit.[17][18]

Death of Ahab

After some years, Ahab with Jehoshaphat of Judah went to recover Ramoth-Gilead from the Arameans.[6] During this battle, Ahab disguised himself, but he was mortally wounded by an unaimed arrow.[17] The Hebrew Bible says that dogs licked his blood, according to the prophecy of Elijah. But the Septuagint adds that pigs also licked his blood, symbolically making him unclean to the Israelites, who abstained from pork. Ahab was succeeded by his sons, Ahaziah and Jehoram.[19]

Jezebel's death, however, was more dramatic than Ahab's. As recorded in 2 Kings 9:30–34, Jehu had his servants throw Jezebel out of a window, causing her death. The dogs ate Jezebel's body, leaving nothing but her skull, her feet, and the palms of her hands, as prophesied by Elijah.

Legacy

1 Kings 16:29 through 22:40 contains the narrative of Ahab's reign. His reign was slightly more emphasized upon than the previous kings, due to his blatant trivialization of the "sins of Jeroboam", which the previous kings of Israel were plagued by, and his subsequent marriage with a pagan princess, the nationwide institution of Baal worship, the persecution of Yahweh's prophets and Naboth's shocking murder. These offenses and atrocities stirred up populist resentment from figures such as Elijah and Micaiah. Indeed, he is referred to by the author of Kings as being "more evil than all the kings before him".[20][6]

Nonetheless, there were achievements that the author took note of, including his ability to fortify numerous Israelite cities and build an ivory palace.[21] Adherents of the Yahwist religion found their principal champion in Elijah. His denunciation of the royal dynasty of Israel and his emphatic insistence on the worship of Yahweh and Yahweh alone, illustrated by the contest between Yahweh and Baal on Mount Carmel,[22] form the keynote to a period that culminated in the accession of Jehu, an event in which Elijah's chosen disciple Elisha was the leading figure and the Omride Dynasty was brutally defeated.[6]

In Rabbinic literature

Ahab was one of the three or four wicked kings of Israel singled out by tradition as being excluded from the future world of bliss (Sanh. x. 2; Tosef., Sanh. xii. 11). Midrash Konen places him in the fifth department of Gehenna, as having the heathen under his charge. Though held up as a warning to sinners, Ahab is also described as displaying noble traits of character (Sanh. 102b; Yer. Sanh. xi. 29b). Talmudic literature represents him as an enthusiastic idolater who left no hilltop in the Land of Israel without an idol before which he bowed, and to which he or his wife, Jezebel, brought his weight in gold as a daily offering. So defiant in his apostasy was he that he had inscribed on all the doors of the city of Samaria the words, "Ahab hath abjured the living God of Israel." Nevertheless, he paid great respect to the representatives of learning, "to the Torah given in twenty-two letters," for which reason he was permitted to reign for twenty-two successive years. He generously supported the students of the Law out of his royal treasury, in consequence of which half his sins were forgiven him. A type of worldliness (Ber. 61b), the Crœsus of his time, he was, according to ancient tradition (Meg. 11a), ruler over the whole world. Two hundred and thirty subject kings had initiated a rebellion; but he brought their sons as hostages to Samaria and Jerusalem. All the latter turned from idolaters into worshipers of the God of Israel (Tanna debe Eliyahu, i. 9). Each of his seventy sons had an ivory palace built for him. Since, however, it was Ahab's idolatrous wife who was the chief instigator of his crimes (B. M. 59a), some of the ancient teachers gave him the same position in the world to come as a sinner who had repented (Sanh. 104b, Num. R. xiv). Like Manasseh, he was made a type of repentance (I Kings, xxi. 29). Accordingly, he is described as undergoing fasts and penances for a long time; praying thrice a day to God for forgiveness, until his prayer was heard (PirḲe R. El. xliii). Hence, the name of Ahab in the list of wicked kings was changed to Ahaz (Yer. Sanh. x. 28b; Tanna debe Eliyahu Rabba ix, Zuṭṭa xxiv.).[23]

Pseudo-Epiphanius ("Opera," ii. 245) makes Micah an Ephraimite. Confounding him with Micaiah, son of Imlah,[24] he states that Micah, for his inauspicious prophecy, was killed by order of Ahab through being thrown from a precipice, and was buried at Morathi (Maroth?; Mic. i. 12), near the cemetery of Enakim (Ένακεὶμ Septuagint rendering of ; ib. i. 10). According to "Gelilot Ereẓ Yisrael" (quoted in "Seder ha-Dorot," i. 118, Warsaw, 1889), Micah was buried in Chesil, a town in southern Judah (Josh. xv. 30).[25] Naboth's soul was the lying spirit that was permitted to deceive Ahab to his death.[26]

In popular culture

Ahab is portrayed by Eduard Franz in the film Sins of Jezebel (1953). He is also the namesake of Captain Ahab in Moby Dick by Herman Melville.

Explanatory notes

- See 1 Kings 16:31, 18:4–19, 19:1–2, 21:5–25

Citations

- 1 Kings 16:29–34

- Finkelstein & Silberman 2002, pp. 169–195.

- 1 Kings 16:29

- Thiele 1965.

- Coogan 2009, p. 237.

- Cook 1911, pp. 428–429.

- 1 Kings 16:32

- Craig 1887, pp. 201–232.

- Coogan 2009, p. 243.

- Ussishkin 2010.

- 1 Kings 17:1

- 1 Kings 18:17–40

- 1 Kings 20:34–43

- 1 Kings 21:1–16

- 1 Kings 21:19

- 1 Kings 21:27

- 1 Kings 22

- Achtemeier 1996, p. 18.

- Coogan 2009.

- 1 Kings 16:30

- 1 Kings 22:39

- 1 Kings 18

- McCurdy & Kohler 1906.

- 1 Kings 22:8

- Singer et al. 1906.

- Rosenfeld, Dovid (January 26, 2019). "The Lying Spirit Which Deceived Ahab". aishcom. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

General and cited references

- Achtemeier, Paul, ed. (1996). The HarperCollins Bible Dictionary. New York: HarperCollins.

- Coogan, Michael David (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament: The Hebrew Bible in Its Context. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533272-8.

- Craig, James A. (1887). "The Monolith Inscription of Salmaneser II". Hebraica. 3 (4): 201–232. doi:10.1086/368966. JSTOR 527096.

- Cook, Stanley Arthur (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 428–429.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-2338-6.

McCurdy, J. Frederic; Kohler, Kaufmann (1906). "Ahab". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

McCurdy, J. Frederic; Kohler, Kaufmann (1906). "Ahab". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Singer, Isidore; Seligsohn, M.; Schechter, Solomon; Hirsch, Emil G. (1906). "Micah". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Singer, Isidore; Seligsohn, M.; Schechter, Solomon; Hirsch, Emil G. (1906). "Micah". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.- Thiele, Edwin Richard (1965). The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings: A Reconstruction of the Chronology of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah. Paternoster Press.

- Ussishkin, David (2010). "Jezreel–Where Jezebel Was Thrown to the Dogs". Biblical Archaeology Review. 36 (4).

External links

Media related to Ahab at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ahab at Wikimedia Commons