King's Regiment

The King's Regiment, officially abbreviated as KINGS, was an infantry regiment of the British Army, part of the King's Division. It was formed on 1 September 1958 by the amalgamation of the King's Regiment (Liverpool) which had been raised in 1685 and the Manchester Regiment which traced its history to 1758. In existence for almost 50 years, the regular battalion, 1 KINGS, served in Kenya, Kuwait, British Guiana (Guyana), West Germany, Northern Ireland, the Falkland Islands, Cyprus, and Iraq. Between 1972 and 1990, 15 Kingsmen died during military operations in Northern Ireland during a violent period in the province's history known as "The Troubles".

| The King's Regiment | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1 September 1958 – 1 July 2006 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Role | Line infantry |

| Size | One regular battalion and one Territorial Army battalion |

| Part of | King's Division |

| Garrison/HQ | Regimental Headquarters, Liverpool |

| Nickname(s) | Kingos |

| Motto(s) | Nec Aspera Terrent (Difficulties be Damned) |

| March | Quick: The Kingsman Slow: Lord Ferrar's March: Song, The Kings are coming up the hill |

| Anniversaries | Ladysmith (28 February), Kohima (15 May), Guadeloupe (10 June), Somme (1 July), Blenheim (13 August), Delhi (14 September), Inkerman (5 November) |

| Commanders | |

| Last Colonel in Chief | Prince Charles |

| Insignia | |

| Tactical Recognition Flash |  |

When formed in 1958, the King's Regiment consisted of one infantry battalion, known within the Army as 1 KINGS, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Derek Horsford. Under a system known colloquially as the "Arms plot", infantry battalions were trained and equipped for different roles for a period of between two and six years. Converted first to a mechanized battalion equipped with FV432 armoured personnel carriers in the late 1960s in West Germany (the Federal Republic of Germany), it converted back to a light battalion in UK and subsequently in Hong Kong and Northern Ireland, back to a mechanized battalion in 1980 and then again to a light battalion. Prior to and during Op Telic Iraq in 2003 the regiment was roled as an armoured infantry regiment, equipped primarily with the Warrior infantry fighting vehicle; it continued this role during the amalgamation in 2006. The regimental establishment in 2004 was 620, although its substantive strength was recorded as being 60 below that.[1]

History

1958–1980

The King's and Manchester Regiments, consisting of regular and Territorial Army battalions, had been selected for amalgamation by Duncan Sandys' 1957 Defence White Paper. Conscription (National Service) was to be abolished and the Armed Forces' size rationalised over a gradual period.[2] Retired soldiers and some serving personnel despaired at the prospect of the demise of their respective regiments.[3] The regular 1st battalions of both regiments formally amalgamated on 1 September 1958, at Brentwood, to form the 1st Battalion, King's Regiment (Manchester and Liverpool). The title reflected the seniority of the King's Regiment (Liverpool), formerly eighth in the infantry's order of precedence. Regimental subtitles (i.e. Manchester and Liverpool) would be omitted in 1968 without affecting recruitment boundaries in North West England. The regiment inherited from its predecessors certain traditions, uniform distinctions, battle honours, and an association with the Royal Family, principally Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother. As Queen of the United Kingdom in 1947, Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon had assumed the position of Colonel-in-Chief of the Manchester Regiment, formalising a relationship conceived during the Second World War.[4]

Queen's and Regimental colours were presented to the 1st Battalion by the 18th Earl of Derby on 28 November. In addition to 1 KINGS, the regiment at that time consisted of three territorial battalions, all of which retained their historical designations, colours, uniforms, and honorary colonels. This practice continued until the Territorial Army's restructuring in the late 1960s: the 5th Battalion, The King's Regiment (Liverpool), was reduced to a company of the Lancastrian Volunteers; the 8th (Ardwick) Battalion, The Manchester Regiment amalgamated with the 9th Battalion, to form The Manchester Regiment (Ardwick and Ashton) Territorials and a separate company within The Lancastrian Volunteers. Other units were constituted by elements of The King's Regiment and its predecessors, albeit in different services of the Army. Personnel from the Liverpool Scottish and defunct 5 KINGS became part of "R" (King's) Battery, West Lancashire Regiment, Royal Artillery while the heritage of the Liverpool Irish and Liverpool Rifles was claimed by troops of other Royal Artillery batteries.[5][6]

Within months, the regiment received notification that it would be stationed in Kenya, which was emerging from the Mau Mau Uprising and nearing independence. Arriving in 1959, 1 KINGS was accommodated in Gilgil, situated in the Rift Valley between Naivasha and Nakuru, until relocated to Muthaiga Camp, near Nairobi. Detached from the regiment at this time were elements of headquarters and two rifle companies ("A" and "D"), which became part of the Army's contribution to the Persian Gulf garrison in Bahrain for more than a year.[7] Subordinated to 24 Infantry Brigade, which Britain maintained in Kenya as part of the Strategic Reserve, 1 KINGS became liable for deployment to various locations in Africa and Asia.[7]

Subsequent to Kuwait's independence from Britain in June 1961, President Abd al-Karim Qasim directed belligerent speeches against the oil-rich Gulf state, declaring it an integral component of sovereign Iraq.[8] Perceiving Qassim's rhetoric to constitute a possible military threat to Kuwait's sovereignty, Sheikh Abdullah III appealed to Britain and Saudi Arabia for assistance. Britain responded to the emergency by concentrating military forces in the Persian Gulf, composed initially of naval assets, as a deterrence to aggression.[9] The Strategic Reserve's 24 Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Horsford, was transported to Kuwait in Bristol Britannias in early July to augment the country's defences. Opportunity for the Kingsmen to acclimatise before relieving 45 Commando was fleeting. Just days after arrival, 1 KINGS occupied a ridge formation approximately 30-miles west of Kuwait City to prepare a defensive position.[10]

When the emergency ended, 1 KINGS returned to Kenya, and in early 1962 proceeded to Britain. By July, the regiment was based in West Berlin. While there, the regiment patrolled the border with Soviet occupied East Berlin. On returning to Britain in 1964, 1 KINGS became part of the UK Strategic Reserve. A company from the regiment deployed to British Honduras later that year.[11]

The battalion's first deployment to Northern Ireland under the hostile conditions of the Troubles occurred in 1970, although it did not suffer its first fatal casualties until a second tour in 1972. Violence escalated substantially in 1972, resulting in the deaths of 470 people.[12] The year witnessed the greatest loss of life during the conflict – punctuated by two episodes known as Bloody Sunday and Bloody Friday – and imposition of direct rule following the prorogation of the Stormont Parliament by the Westminster Government.[13] Operating in West Belfast, 1 KINGS sustained 49 casualties (seven fatalities and 42 wounded) during the four-month tour.[14] The King's first fatality was Corporal Alan Buckley, who died after being mortally wounded during an engagement with the PIRA. One-week later, on 23 May, a PIRA sniper shot Kingsman Hanley, who had been guarding a party of Royal Engineers removing barricades in the Ballymurphy sector.[15] On the 30th, an IRA bomb detonated within the battalion headquarters killed two, including Kingsman Doglay.[16] An initial report by The Times identified six casualties, including four wounded soldiers and two civilian cooks, and suggested officials believed losses would have been higher had the bomb exploded while hundreds of soldiers watched a film in the canteen. The headquarters, located in RUC Springfield Road, had been the "most heavily guarded" police station in Belfast.[17] The battalion returned to Belfast in February 1979.[11] In April 1979 Kingsman Shanley and Lance Corporal Rumble were killed in the same vehicle by a PIRA sniper.[18]

1980–2000

Events were organised in 1985 to observe the tercentenary of the regiment's raising in 1685 as the Princess Anne of Denmark's Regiment of Foot. After returning to England, to be based at Saighton Camp just outside Chester, then later to Dale Barracks Chester when Saighton Camp closed in 1985, 1 KINGS deployed to the Falkland Islands for four months and then again to Northern Ireland in May 1986.[11]

Northern Ireland remained the British Army's largest operational commitment into the early 1990s. Violence had declined in frequency and casualties reduced in number; however, a new method of attack emerged during the regiment's two-year posting to County Londonderry as a resident infantry battalion in 1990.[19] The attack on 1 KINGS was the first in a series of vehicle-delivered "proxy bomb" attacks against multiple targets in 1990, three of which occurred on 24 October. Three men accused by the PIRA of collaborating with the security forces were abducted and their families held hostage. Employed by the British Army as a civilian cook, Patrick Gillespie was instructed to drive his vehicle, laden with explosives, to a designated checkpoint on the border with County Donegal, Republic of Ireland. Approximately 1,000 pounds of explosives contained within Gillespie's vehicle was detonated remotely when it reached the permanent checkpoint on Buncrana Road, near Derry, wounding many and killing Lance-Corporal Burrows and Kingsmen Beecham, Scott, Sweeney and Worrall.[20] Structural damage to buildings in a nearby housing estate and to military infrastructure was extensive.[20]

In 1992 1 KINGS moved to west London to serve as a Public Duties Battalion.[11] Almost immediately it received new Colours from the Colonel in Chief. Whilst in London one platoon was detached to 1 KINGS OWN BORDER in Derry whilst two platoons were attached from the newly formed The Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment, abbreviated PWRR. A company reinforced by one of the PWRR platoons deployed as the Resident Infantry Company to the Falkland Islands and South Georgia for a four-month tour of duty. However the principal task of the battalion was to provide troops to guard Buckingham Palace, St James's Palace, HM Tower of London and Windsor Castle. As Public Duties came to an end in September 1994, the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Robin Hodges, handed over command to his brother, Lieutenant Colonel Clive Hodges. Another tour-of-duty to Northern Ireland followed in 1995. The battalion moved to the Sovereign Base Areas in Cyprus the following year.[11] After returning to Britain, further deployments to Northern Ireland followed in 1999.[11]

2000–2006

Prior to the firefighters' strikes of 2003, the regiment received basic firefighting training to provide emergency cover. The battalion operated in the Greater Manchester area during the strikes as part of Operation Fresco.

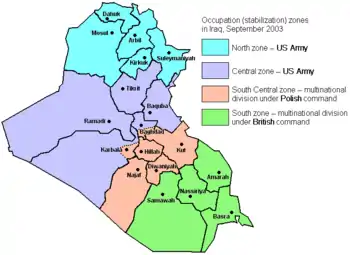

Almost two-months after President George W. Bush declared an end to "major combat operations" in Iraq in his "Mission Accomplished" speech on 1 May 2003, 1 KINGS reinforced from the Territorial Army King's and Cheshire Regiment deployed to the country with 19 Mechanised Brigade. Under command of Lieutenant-Colonel Ciaran Griffin, 1 KINGS Battlegroup operated primarily in Basra Province during the initial period of post-war occupation. Tactics, familiar to the Regiment, that had been employed in Northern Ireland and the Balkans, were adopted by the British forces occupying the south of Iraq.[21] Unless conditions dictated the wearing of helmets and deployment of Warriors, 1 KINGS disembarked from Land Rovers to conduct foot patrols in "soft hats" (berets).[22][23] During its tour, 1 King's organised vehicle checkpoints, seized munitions, trained local forces, mediated tribal disputes, and engaged in a "hearts and minds" campaign.[24] Civil disorder also occupied the battalion, particularly when rioting occurred in August and October. The British attributed the violent demonstrations in August to Iraqi grievances over the scarcity of fuel and power shortages, compounded by oppressive temperatures exceeding 50 °C (122 °F).[25]

The Kingsmen returned to Catterick in November 2003. No fatal casualties had been incurred by the regiment and two officers and a Territorial Army soldier were decorated with operational gallantry awards in recognition of their contributions.[26] Allegations of abuse were documented seven months later in a report published by Amnesty International on 11 May 2004. Coinciding with a controversy centred on the publication of unrelated photographs by the Daily Mirror newspaper, the report detailed the deaths of 37 civilians, including four Iraqis that were claimed to have been killed by members of 1 KINGS Battlegroup without apparent provocation.[27] The circumstances of their deaths were disputed and senior British officers judged the actions of the soldiers responsible to have been in compliance with the Army's rules of engagement.[28] Iraqi families brought their cases to the High Court of Justice in an attempt to secure independent inquiries and compensation.[29] The court, presided over by Lord Justice Rix and Justice Forbes, concluded in December that British jurisdiction did not extend to "the total territory of another state which is not itself a party to the Convention", prompting the families to challenge the judgement in the Court of Appeal.[28][30] Their appeals were dismissed in December 2005.[31]

In December 2004, it was announced that The King's Regiment, the King's Own Royal Border Regiment and the Queen's Lancashire Regiment, would be amalgamated to form The Duke of Lancaster's Regiment (King's, Lancashire and Border) as part of the restructuring of the infantry. On formation of the new regiment on 1 July 2006, 1 KINGS became the 2nd Battalion The Duke of Lancaster's Regiment, abbreviated as 2 LANCS, but very quickly the manpower of all three merging regiments was deliberately mixed to give the new regiment its own character.[32]

Territorials

When the regiment was created, all three of the remaining Territorial battalions from both the King's and Manchesters, were transferred without a change in title. These were:[33]

- 5th Battalion, King's Regiment (Liverpool); at Townsend Avenue, Liverpool

- 8th (Ardwick) Battalion, Manchester Regiment; at Ardwick Green, Manchester

- 9th Battalion, Manchester Regiment; at Ashton-under-Lyne

In 1967 when the TAVR was created, the 3 Battalions were reduced to 2 companies of the Lancastrian Volunteers. 5th King's, became B Company (King's); whilst both 8th and 9th Manchesters became C Company (Manchester).

5th/8th (Volunteer) Battalion

However, this regiment didn't last very long, and in 1975 control of the Territorial units was placed back under the affiliated regiments. Therefore, HQ, B, and C Companies, 1st Battalion, Lancastrian Volunteers, alongside B Company (later D Company) of the 2nd Battalion were redesignated as the 5th/8th (Volunteer) Battalion of the King's Regiment. Upon formation, the battalion's structure was as follows:[34][35]

- HQ Company, at Warrington

- A Company, at Warrington

- B Company, at Townsend Avenue, Liverpool

- C Company, at Ardwick Green, Manchester

- D Company, at Townsend Avenue, Liverpool

1984 saw the creation of a Home Service Force company- E (HSF) Company, with platoons spread throughout the company locations. The HSF was disbanded, however, in 1992 at the end of the Cold War, and therefore so was the company. At the same time as E Company disbanded, the battalion was reduced down to three rifle companies, and retained this structure until amalgamation in 1999.[34][35]

- HQ (The Lancastrian) Company, at Warrington

- A (The King's Liverpool) Company, at Townsend Avenue, Liverpool

- C (The Manchester) Company, at Ardwick Green, Manchester

- V (The Liverpool Scottish) Company, at Score Lane, Liverpool (transferred from 1st Battalion, 51st Highland Volunteers)

The Battalion amalgamated with the 3rd (Volunteer) Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment, in 1999, to form the King's and Cheshire Regiment; A and V Companies amalgamated as A (King's) Company, and C Company was redesignated as C (King's) Company, of the new regiment. The King's Companies of the King's and Cheshire Regiment, later went on to amalgamate with the Lancastrian and Cumbrian Volunteers to form 4th Battalion, Duke of Lancaster's Regiment.[36]

Other information

Battle honours

from the Regiment and its predecessors

- 18th Century:

- 19th Century:

- The Great War 1914–1918:

- Western Front: Mons, Retreat from Mons, Marne 1914, Aisne 1914, Ypres 1914 1917, La Bassée, Armentières, Langemarck 1914 -17, Gheluvelt, Battle of Nonne Bosschen, Givenchy 1914, Neuve Chapelle, Gravenstafel, St Julien, Frezenberg, Bellewaarde, Battle of Aubers, Festubert 1915, Loos, Somme 1916–17, Albert 1916 -1918, Bazentin, Delville Wood, Guillemont, Ginchy, Flers-Courcelette, Morval, Thiepval, Le Transloy, Ancre Heights, Ancre 1916 1918, Bapaume 1917 1918, Arras 1917 -1918, Battle of the Scarpe 1917 & 1918, Arleux, Bullecourt, Pilckem, Menin Road, Polygon Wood, Broodseinde, Poelcappelle, Passchendaele, Cambrai 1917 and 1918, St Quentin, Rosières, Avre, Lys, Estaires, Messines 1918, Bailleul, Kemmel, Bethune, Scherpenberg, Amiens, Drocourt-Quéant, Hindenburg Line, Epéhy, Canal du Nord, St. Quentin Canal, Beaurevoir, Courtrai, Selle, Sambre, France and Flanders 1914–18

- Italy: Piave, Vittorio Veneto, Italy 1917–18,

- Macedonia: Doiran 1917, Macedonia 1915–18

- Gallipoli Campaign: Helles, Battle of Krithia, Suvla, Landing at Suvla, Scimitar Hill, Gallipoli 1915

- Mesopotamia: Tigris 1916, Kut al Amara, Baghdad, Mesopotamia 1916–18

- Egypt and Palestine: Rumani, Egypt 1915–17, Megiddo, Sharon, Palestine 1918

- Other Theatres: NW Frontier, India 1915, Archangel 1918–1919

- Inter-War:

- The Second World War 1939–45:

- North-West Europe: The Dyle, Withdrawal to Escaut, Defence of Escaut, Defence of Arras, St Omer-La Bassée, Ypres-Comines Canal, North-West Europe 1940, Normandy landings, Caen, Esquay, Falaise, Niederrijn, Scheldt, Walcheren Causeway, Flushing, Lower Maas, Venlo Pocket, Roer, Ourthe, Rhineland, Reichswald, Goch, Weeze, Rhine, Ibbenbüren, Drierwalde, Aller, Bremen, North-West Europe 1944–45

- Italy: Cassino II, Trasimene Line, Tuori, Gothic Line, Monte Gridolfo, Coriano, San Clemente, Gemmano Ridge, Montilgallo, Capture of Forli, Lamone Crossing, Lamone Bridgehead, Rimini Line, Montescudo, Cesena, Italy 1944–45

- Asia: Singapore Island, Malaya 1941–1942, Chindits 1943, Chindits 1944, North Arakan, Kohima, Pinwe, Shwebo, Myinmu Bridgehead, Irrawaddy, Burma 1943 1944–1945

- Other Theatres: Malta 1940, Athens, Greece 1944–45

- Korean War:

Colonels-in-Chief

Colonels-in-Chief were:[37]

- 1958–2002: HM Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother

- 2003–2006: Lt-Gen. HRH Prince Charles, Prince of Wales, KG, KT, GCB, AK, QSO, ADC

Regimental Colonels

Colonels of the Regiment were:[37]

- 1958–1962: Maj-Gen. Thomas Bell Lindsay Churchill, CB, CBE, MC (from the Manchester Regiment)

- 1962–1965: Maj-Gen. George Douglas Gordon Heyman, CBE

- 1965–1970: Maj-Gen. Derek Gordon Thomond Horsford, CBE, DSO

- 1970–1975: Brig. Arthur Eric Holt

- 1975–1986: Col. Sir Geoffrey F. Errington, Bt.

- 1986–1994: Brig. Peter Ronald Davies, CB

- 1994–2002?: Brig. Jeremy John Gaskell, OBE

- 2002?–2006: Col. Malcolm Grant Howarth, CBE

- 2006: Regiment merged with The King's Own Royal Border Regiment and The Queen's Lancashire Regiment to form The Duke of Lancaster's Regiment (King's, Lancashire and Border)

Notes

- House of Commons Written Answers, 10 January 2005. Retrieved 23 June 2007.

- Chandler (2003), p338

- Mileham (2000), p193

- Mills, T.F. "The King's Regiment". regiments.org. Archived from the original on 5 May 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Mileham (2000), p203

- Regiments.org

- Mileham (2000), p195

- Speller (2005), The Royal Navy and Maritime Power in the Twentieth Century, p166

- Tripp (2002), History of Iraq, pp165-166

- Mileham (2000), p196

- "King's Regiment". British Army units 1945 on. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- The Police Service of Northern Ireland records the deaths of 148 security personnel, including 131 soldiers, and 322 civilians, including members of Republican and Loyalist paramilitary organisations. Additionally, there were 10,631 reported shooting incidents and 1,853 attempted bomb attacks, of which 1,382 resulted in detonation. Security and Defence, CAIN, cain.ulst.ac.uk. Retrieved 22 June 2008.

- Reitan, Earl A. (2003), The Thatcher Revolution: Margaret Thatcher, John Major, Tony Blair and the Transformation of Modern Britain 1979–2002, p111

- Mileham (2000), p208

- Mileham (2000), p206

- Mileham (2000), p207

- Cashinella, Brian (1972), Two IRA Leaders are Arrested by Éire Police, The Times, 1 June 1972, p1

- "King'sRegiment". Palace Garden. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- Cox, Guelke & Stephen (2000), A Farewell to Arms?: Beyond the Good Friday Agreement, p213

- Brooke (1990), House of Commons Hansard Debates, 24 October, publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- Coalition divided over battle for hearts and minds, guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 13 June 2007.

- Greste (2003), Business as usual for British forces in Iraq, news.bbc.co.uk

- Russell (2003), British troops patrol Basra using low-key tactics, alertnet.org (Reuters).

- Neely (2003), Crime-racked Basra calls on British troops to get tougher, The Independent, 23 October. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- BBC (2003), UK troops attacked in Basra, 9 August, news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- For services in Iraq, Major James Benjamin Weston Hollister and Lance-Corporal Michael Davidson were awarded the Military Cross for "gallantry during active operations against the enemy"; Captain Taitusi Kagi Saukuru was awarded the (Queen's Gallantry Medal) for "displaying great composure under pressure" and "outstanding leadership and professionalism of the highest order". In addition Lieutenant Colonel Ciaran Munchin Griffin received an OBE and Major Andrew Michael Pullan and Kingsman Paul Dennis Vanden were mentioned in despatches. Operational Honours and Awards Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, gnn.gov.uk. Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- UK troops 'shot harmless Iraqis', news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- High Court publication Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, hmcourts-service.gov.uk. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- BBC (2004), Court challenge over Iraqi deaths, 5 May, news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- BBC (2004), Iraqis win death probe test case, news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- "Appeal Decision" (PDF). Redress. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- "Duke of Lancaster's Regiment". Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- "The King's Regiment". Archived from the original on 5 May 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- "5th/8th (Volunteer) Battalion The King's Regiment". Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- "5th/8th Battalion, The King's Regiment". Archived from the original on 16 August 2007.

- "The King's and Cheshire Regiment". Archived from the original on 7 March 2002. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- "The Kings Regiment". regiments.org. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

References

- Chandler, David (2003), The Oxford History of the British Army, Oxford Paperbacks ISBN 0-19-280311-5

- Mileham, Patrick (2000), Difficulties Be Damned: The King's Regiment – A History of the City Regiment of Manchester and Liverpool, Fleur de Lys ISBN 1-873907-10-9

- History of the Duke of Lancaster's Regiment, army.mod.uk