Khaemweset

Prince Khaemweset (also translated as Khamwese, Khaemwese or Khaemwaset or Setne Khamwas)[1][2] was the fourth son of Ramesses II and the second son by his queen Isetnofret. His contributions to Egyptian society were remembered for centuries after his death.[3] Khaemweset has been described as "the first Egyptologist" due to his efforts in identifying and restoring historic buildings, tombs and temples.

| Khaemwaset in hieroglyphs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Khaemwaset ḫꜥ m wꜣst "He who appeared in Thebes" | |||||||

| |||||||

Life

According to historian Miriam Lichtheim:[2]

- Here I should like to stress that Prince Setne Khamwas, the hero of the two tales named for him, was a passionate antiquarian. The historical prince Khamwas, was the fourth son of King Ramses II, had been high priest of Ptah at Memphis and administrator of all the Memphite sanctuaries. In that capacity he had examined decayed tombs, restored the names of their owners, and renewed their funerary cults. Posterity had transmitted his renown, and the Demotic tales that were spun around his memory depicted him and his fictional adversary Prince Naneferkaptah as very learned scribes and magicians devoted to the study of ancient monuments and writings.

Youth and military training

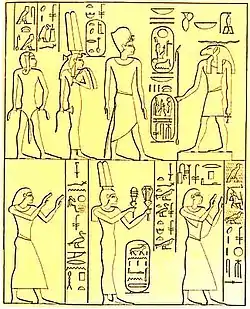

Khaemweset was the second son of Ramesses II and Queen Isetnofret. He was born during the reign of his grandfather Pharaoh Seti I and the fourth son overall. In about the 13th year of the reign of Seti I, crown-prince Ramesses put down a minor revolt in Nubia. Ramesses took his small sons Amunherwenemef and Khaemweset with him on this military campaign. Khaemweset may have been only 4 years old at this time. Khaemweset and his older brother are shown making a charge on the battle field in a chariot. The events were recorded in scenes in the temple at Beit el Wali.[4]

Khaemweset grew up with his brothers during a time of foreign conflict and he is present in scenes from the Battle of Kadesh, the siege of Qode (Naharin), and the siege of Dapur in Syria. In the battle of Kadesh scenes from year 5 of Ramesses II, Khaemweset is shown leading sons of the chiefs of Hatti before the gods. These princes were prisoners of war. In scenes depicting the battle of Qode, Khaemweset is shown both leading prisoners before his father and serving as an attendant of his father. In year 10 of Ramesses II Khaemweset is present during the battle of Dapur.[5]

Priesthood

After this initial period where Khaemweset may have had some military training, or at least was present at the battlefield, he became a Sem-Priest of Ptah in Memphis. This appointment occurred in c. Year 16 of Ramesses II's reign. He would have initially been a deputy to the High Priest of Ptah in Memphis named Huy. During his time as Sem-Priest Khaemweset was quite active in rituals, including the burial of several Apis bulls at the Serapeum of Saqqara. In year 16 of Ramesses, the Apis bull died and was buried in the Serapeum. Funerary gifts were presented by the High Priest of Ptah, Huy, Khaemweset himself, his brother Prince Ramesses, and Vizier Paser. The next burial took place in year 30 and at that time the gifts came from the chief of the treasury Suty and the Mayor of Memphis named Huy. After this second burial Khaemweset redesigned the Serapeum. He created an underground gallery where a series of burial chambers allowed for the burial of several Apis bulls.[4]

Heb-Sed festivals

Around the 25th regnal year of his father, his older brother Ramesses became crown prince, and in the 30th year, Khaemweset's name started to appear in the announcements of the Sed festivals. These were traditionally held in Memphis, but some of the announcements were made in Upper Egypt at El Kab and Gebel el-Silsila. While he was a Sem priest, Khaemweset may have constructed and built additions to the temple of Ptah in Memphis. There are several inscriptions which attest to Khaemweset's activities in Memphis.[5]

Restoring ancient monuments

Khaemweset restored the monuments of earlier kings and nobles. Restoration texts were found associated with the pyramid of Unas at Saqqara, the tomb of Shepseskaf called the Mastabat al-Fir’aun, the sun-Temple of Nyuserre Ini, the Pyramid of Sahure, the Pyramid of Djoser, and the Pyramid of Userkaf. Inscriptions at the pyramid temple of Userkaf show Khaemweset with offering bearers, and at the pyramid temple of Sahure Khamwaset offers a statue of the goddess Bast.[5]

Khaemweset restored a statue of Prince Kawab, a son of King Khufu. The inscription on the throne reads:

- "It is the Chief Directing Artisans and Sem-Priest, the King's Son, Khaemweset, who was glad over this statue of the King's Son Kawab, and who took it from what was cast (away) for debris (?), in [...] .. of his father, the King of South and North Egypt Khufu. Then the S[em-Priest and King's Son, Kha]em[waset] decreed that [it be given] a place of favor of the Gods in company with the excellent Blessed Spirits at the Head of the Spirit (Ka) chapel of Ro-Setjau, – so greatly did he love antiquity and the noble folk who were aforetime, along with the excellence (of) all that they had made, so well, and repeatedly ("a million times").

These (things) shall be for (for) all life, stability and prosperity, enduring upon earth, [for the Chief Directing Artisans and Sem-Priest, the King's Son, Khaemwaset, after he has (re)established all their cult procedures of this temple, which had fallen into oblivion [in the remembrance] of men.

He has dug a pool before the noble sanctuary (?), in work (agreeing) with his wishes, while pure channels existed, for purity, and to bring libations from (?) the reservoir (?) of Khafre, that he may attain (the status of) "given life".[5]

- "It is the Chief Directing Artisans and Sem-Priest, the King's Son, Khaemweset, who was glad over this statue of the King's Son Kawab, and who took it from what was cast (away) for debris (?), in [...] .. of his father, the King of South and North Egypt Khufu. Then the S[em-Priest and King's Son, Kha]em[waset] decreed that [it be given] a place of favor of the Gods in company with the excellent Blessed Spirits at the Head of the Spirit (Ka) chapel of Ro-Setjau, – so greatly did he love antiquity and the noble folk who were aforetime, along with the excellence (of) all that they had made, so well, and repeatedly ("a million times").

Some of these restorations took place during his later tenure as Sem priest. The work on the pyramid of Djoser is dated to year 36 of Ramesses II. Some of the inscriptions mention Khaemweset's title as "Chief of the Artificers" or "Chief of Crafts". Hence, some of these restorations were undertaken after his promotion as the High Priest of Ptah in Memphis about the 45th year of the reign of Ramesses II.[4]

Family

Khaemweset was the son of Ramesses II and Queen Isetnofret. He had at least two brothers: Prince Ramesses was his elder brother and Merneptah was his younger brother. Bintanath was his sister. These three siblings are depicted on the Aswan Rock stela with the Pharaoh and Queen shown with Khaemweset in another register. It is possible that Princess Isetnofret was a full sister of Khaemwaset as well, although it is equally possible she was only a half-sister.[3]

Khaemweset is known to have had two sons and a daughter. His eldest son, Ramesses, is mentioned on a block statue from Memphis. Ramesses holds the title "King's Son" on the statue, which here should be interpreted as King's grandson. On the Dorsal Pillar the text reads: "[It is] his dear [son] who perpetuates his name - The King's Son, excellent in wisdom, upright in mind in every deed, great in his enlightenment at all times to maintain the offerings for his father, – the King's Son Ramesses, justified and venerated one."[5]

His second son, Hori, became High Priest of Ptah at Memphis during the later part of the 19th Dynasty.

Khaemweset is also known to have had a daughter named Isetnofret (also written as Isitnofret). Other women at court with that name include her grandmother Queen Isetnofret and her father’s sister. Khaemweset's daughter Isetnofret may have married her uncle, the pharaoh Merneptah. If so, she would be identical to Queen Isetnofret II.[3] Isetnofret's tomb may have recently been found in Saqqara during excavations by Waseda University.[6] Not much is known about Khaemweset's wife, though in the demotic story, Setna II, his wife bears the name Meheweskhe.[7]

One grandson of his is known. His son Hori had a son who was also named Hori. This grandson of Khaemweset would later serve as Vizier of Egypt during the tumultuous period at the end of the Nineteenth Dynasty. He was still performing these duties under Ramesses III.

Burial

%252C_son_of_Ramesses_II._The_head_is_missing._Black_steatite._19th_Dynasty._From_Egypt._The_Petrie_Museum_of_Egyptian_Archaeology%252C_London.jpg.webp)

Whilst first exploring the Serapeum of Saqqara between 1851 and 1853, French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette was confronted by a huge rock, which could only be moved by the use of explosives. Once the shattered remnants of the rock were removed, an intact coffin was discovered which contained the mummy of a man, accompanied by numerous funerary treasures. A gold mask covered his face, and amulets gave his name as Prince Khaemweset, son of Ramesses II and builder of the Serapeum. These remains have now been lost but Egyptologists believe that this was not the grave of Khaemweset and that the remains were those of an Apis Bull made into a human form to resemble the Prince.

The Egyptologist Aidan Dodson is quoted writing in his book "Canopic Equipment from the Serapeum of Memphis":

- "Designated Apis XIV, it comprised a wooden sarcophagus, largely embedded in the ground, with its upper part largely crushed. Inside, there was what had the appearance of a human mummy, its face covered by a somewhat crude gold mask, damaged by damp and bearing a considerable quantity of jewelry, some bearing the name of Prince Khaemweset.

- In spite of its appearance, the mummy proved to be a mass of fragrant resin, containing a quantity of disordered bone. Although frequently stated to be the mummy of Khaemweset, on the basis of its possessing his jewelry, the mass of resin containing bony fragments is far more reminiscent of the undoubted Apis of tombs E and G. Its formation into the simulacrum of a human mummy also finds echo in the anthropoid coffin lids that covered the resinous masses within the sarcophagi of Apis VII and IX, there can thus be no doubt that the burial is actually that of the bull, Apis XIV."[8]

.jpg.webp)

During earlier excavations the Waseda University expedition found the remains of a monument which may have been Khaemweset's "ka-house". [9]

Khaemweset in Ancient Egyptian fiction

In later periods of Egyptian history, Khaemweset was remembered as a wise man, and portrayed as the hero in a cycle of stories dating to the Hellenistic period.[3] In these stories his name is Setne, a distortion of the real Khaemwaset's title as setem-priest of Ptah; modern scholars call this character "Setne Khamwas".[10]

The first tale, dubbed Setne I or Setne Khamwas and Naneferkaptah, describes how Khaemwaset seeks and finds a book of powerful magical spells, the Book of Thoth, in the tomb of Prince Naneferkaptah. Against the wishes of Naneferkaptah's spirit, Khaemwaset takes the book and becomes cursed. Setne then meets a beautiful woman who seduces him into killing his children and humiliating himself in front of the pharaoh. He discovers that this episode was an illusion created by Neferkaptah, and in fear of further retribution, Setne returns the book to Neferkaptah's tomb. At Neferkaptah's request, Setne also finds the bodies of Neferkaptah's wife and son and buries them in Neferkaptah's tomb, which is then sealed.[11]

The second tale is known as Setne II or the Tale of Setne Khamwas and Si-Osire. Khaemwaset and his wife have a son named Si-Osire who turns out to be a highly skilled magician. In the first part of the story, Si-Osire brings his father to visit the Duat, the land of the dead, where they see the pleasant fate of the deceased spirits who lived justly and the torments inflicted on spirits who sinned during their lives. In the second part, it is revealed that Si-Osire is actually a famous magician from the time of Thutmose III who returned to save Egypt from a Nubian magician. After the confrontation, Si-Osire disappears, and Khaemwaset and his wife have a real son who is also named Si-Osire in honor of the magician.[12]

Popular culture

- Khaemwaset appears in the game Age of Mythology under the name of Setna, where he is portrayed as a priest of Osiris rather than Ptah.

- Khaemwaset is the protagonist of Pauline Gedge's novel "Scroll of Saqqara".[13] it is directly inspired by the Setne I tale, but with many changes.

- Khaemwaset appears in The Serpents Shadow, the final book in The Kane Chronicles, as the evil magician Setne, although he is also referred to as Prince Khaemwaset. His character additionally appears in the Kane Chronicles short story The Crown of Ptolemy.

- Khaemwaset is a main character in Saviour Pirotta's The Crocodile Curse, the second book in The Nile Adventures series[14]

See also

Bibliography

- M. Ibrahim Aly, À propos du prince Khâemouaset et de sa mère Isetneferet, in: Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Abteilung Kairo 49 (MDAIK 1993) 97-105.

References

- "BBC - History - Ancient History in depth: The 'Death in Sakkara' Gallery". Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- Miriam Lichtheim. "Ancient Egyptian Literature Vol III".

- Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson (2004), p. 170-171

- Kitchen, Kenneth A., Pharaoh Triumphant: The Life and Times of Ramesses II, King of Egypt, Aris & Phillips. 1983, pp 40, 89, 102-109, 162, 170, 227-230. ISBN 978-0-85668-215-5

- Kitchen, K.A., Ramesside Inscriptions, Translated & Annotated, Translations, Volume II, Blackwell Publishers, 1996

- Tomb of Isetnofret Discovered in Saqqara Archived 2009-03-09 at the Wayback Machine

- William Kelly Simpson and Robert Kriech Ritner, The Literature of Ancient Egypt, Yale University Press (2003), p. 490

- Aidan Dodson, Canopic Equipment from the Serapeum of Memphis, A. Leahy and W.J. Tait (eds) (1999)

- YOSHIMURA, Sakuji and Izumi H. TAKAMIYA, "Waseda University excavations at North Saqqara from 1991 to 1999", in: Abusir and Saqqara 2000, 161-172. (map, plan, fig., pl.)

- Lichtheim, Miriam, Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume III: The Late Period, University of California Press, 2006 [1980], pp. 125–126

- Lichtheim 2006, pp. 127–137

- Lichtheim 2006, pp. 138–151

- "Scroll of Saqqara". www.goodreads.com. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- "The Crocodile Curse".

External links

Media related to Khaemweset at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Khaemweset at Wikimedia Commons- Prince Khaemwaset

- Khaemwaset - Nozomu Kawai. The Encyclopedia of Ancient History DOI: 10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah15225