Kentrosaurus

Kentrosaurus (/ˌkɛntroʊˈsɔːrəs/ KEN-troh-SOR-əs; lit. 'prickle lizard') is a genus of stegosaurid dinosaur from the Late Jurassic in Lindi Region of Tanzania. The type species is K. aethiopicus, named and described by German palaeontologist Edwin Hennig in 1915. Often thought to be a "primitive" member of the Stegosauria, several recent cladistic analyses find it as more derived than many other stegosaurs, and a close relative of Stegosaurus from the North American Morrison Formation within the Stegosauridae.

| Kentrosaurus Temporal range: Late Jurassic (Tithonian), | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton, Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Thyreophora |

| Suborder: | †Stegosauria |

| Family: | †Stegosauridae |

| Genus: | †Kentrosaurus Hennig, 1915 |

| Type species | |

| †Kentrosaurus aethiopicus Hennig, 1915 | |

| Synonyms | |

Fossils of K. aethiopicus have been found only in the Tendaguru Formation, dated to the late Kimmeridgian and early Tithonian ages, about 152 million years ago. Hundreds of bones were unearthed by German expeditions to German East Africa between 1909 and 1912. Although no complete skeletons are known, the remains provided a nearly complete picture of the build of the animal. In the Tendaguru Formation, it coexisted with a variety of dinosaurs such as the carnivorous theropods Elaphrosaurus and Veterupristisaurus, giant herbivorous sauropods Giraffatitan and Tornieria, and the dryosaurid Dysalotosaurus.

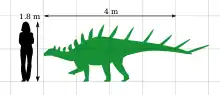

Kentrosaurus generally measured around 4–4.5 metres (13–15 ft) in length as an adult, and weighed about 700–1,600 kilograms (1,500–3,500 lb). It walked on all fours with straight hindlimbs. It had a small, elongated head with a beak used to bite off plant material that would be digested in a large gut. It had a, probably double, row of small plates running down its neck and back. These plates gradually merged into spikes on the hip and tail. The longest spikes were on the tail end and were used to actively defend the animal. There also was a long spike on each shoulder. The thigh bones come in two different types, suggesting that one sex was larger and more stout than the other.

Discovery and naming

The first fossils of Kentrosaurus were discovered by the German Tendaguru Expedition in 1909, recognised as belonging to a stegosaur by expedition leader Werner Janensch on 24 July 1910, and described by German palaeontologist Edwin Hennig in 1915.[1] The name Kentrosaurus was coined by Hennig and comes from the Greek kentron/κέντρον, meaning "sharp point" or "prickle", and sauros/σαῦρος meaning "lizard",[2] Hennig added the specific name aethiopicus to denote the provenance from Africa.[1] Soon after its description, a controversy arose over the stegosaur's name, which is very similar to the ceratopsian Centrosaurus. Under the rules of biological nomenclature, forbidding homonymy, two animals may not be given the same name. Hennig renamed his stegosaur Kentrurosaurus, "pointed-tail lizard", in 1916,[3] while Hungarian paleontologist Franz Nopcsa renamed the genus Doryphorosaurus, "lance-bearing lizard", the same year.[4][5] If a renaming had been necessary, Hennig's would have had priority.[6] However, because the spelling is different, both Doryphorosaurus and Kentrurosaurus are unneeded replacement names; Kentrosaurus remains the valid name for the genus with Kentrurosaurus and Doryphorosaurus being its junior objective synonyms.[7]

Although no complete individuals were found, some material was discovered in association, including a nearly complete tail, hip, several dorsal vertebrae and some limb elements of one individual. These form the core of a mount in the Museum für Naturkunde by Janensch.[8] The mount was dismantled during the museum renovation in 2006/2007, and re-mounted in an improved pose by Research Casting International.[9] Some other material, including a braincase and spine, was thought to have been misplaced or destroyed during World War II.[10] However, all the supposedly lost cranial material was later found in a drawer of a basement cupboard.[11]

From 1909 onwards, Kentrosaurus remains were uncovered in four quarries in the Mittlere Saurierschichten (Middle Saurian Beds) and one quarry in the Obere Saurierschichten (Upper Saurian Beds).[12] During four field seasons, the German Expedition found over 1200 bones of Kentrosaurus, belonging to about fifty individuals,[13] many of which were destroyed during the Second World War.[14] Today, almost all remaining material is housed in the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin (roughly 350 remaining specimens), while the museum of the Institute for Geosciences of the University of Tübingen houses a composite mount, roughly 50% of it being original bones.[12]

In the original description, Hennig did not designate a holotype specimen. However, in a detailed monography on the osteology, systematic position and palaeobiology of Kentrosaurus in 1925, Hennig picked the most complete partial skeleton, today inventorised as MB.R.4800.1 through MB.R.4800.37, as a lectotype (see syntype).[15][16] This material includes a nearly complete series of tail vertebrae, several vertebrae of the back, a sacrum with five sacral vertebrae and both ilia, both femora and an ulna, and is included in the mounted skeleton at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, Germany. The type locality is Kindope, Tanzania, north of Tendaguru hill.[16]

Unaware that Hennig had already defined a lectotype, Peter Galton[17] selected two dorsal vertebrae, specimens MB.R.1930 and MB.R.1931, from the material figured in Hennig's 1915 description, as 'holotypes'. This definition of a holotype is not valid, because Hennig's selection has priority. In 2011, Heinrich Mallison clarified that all the material known to Hennig in 1915, i.e. all the bones discovered before 1912, when Hermann Heck concluded the last German excavations, are paralectotypes, and that MB.R.4800 is the correct lectotype.[18]

Description

Kentrosaurus was a small stegosaur. It had the typical dinosaurian body bauplan, characterised by a small head, a long neck, short forelimbs and long hindlimbs, and a long, horizontal and muscular tail. Typical stegosaurid traits included the elongation and flatness of the head, the powerful build of the forelimbs, erect and pillar-like hindlimbs and an array of plates and spikes running along both sides of the top mid-line of the animal.[15]

Size and posture

Kentrosaurus aethiopicus was a relatively small stegosaur, reaching 4–4.5 m (13–15 ft) in length and 700–1,600 kg (1,500–3,500 lb) in body mass.[8][upper-alpha 1][20][21] Some specimens suggest that relatively larger individuals could have existed.[1][13] These specimens are comparable to some Stegosaurus specimens in terms of the olecranon process in development.[22]

The long tail of Kentrosaurus results in a position of the center of mass that is unusually far back for a quadrupedal animal. It rests just in front of the hip, a position usually seen in bipedal dinosaurs. However, the femora are straight in Kentrosaurus, as opposed to typical bipeds, indicating a straight and vertical limb position. Thus, the hindlimbs, though powered by massive thigh muscles attached to a long ilium, did not support the animal alone, and the very robust forelimbs took up 10 to 15% of the bodyweight.[9] The center of mass was not heavily modified by the osteoderms (bony structures in skin) in Kentrosaurus or Stegosaurus, which allowed the animals to stay mobile despite their armament. The hindlimbs’ thigh muscles were very powerful, allowing Kentrosaurus to reach a tripod stance on its hindlegs and tail.[23]

Skull and dentition

Eight specimens from the skull, mandible, and teeth have been collected an described from the Tendaguru Formation, most of them being isolated elements.[24] Two quadrates (bones from the jaw joint) were referred to Kentrosaurus, but they instead belong to a juvenile brachiosaurid.[25]

.jpg.webp)

The long and narrow skull was small in proportion to the body. It had a small antorbital fenestra, the hole between the nose and eye common to most archosaurs, including modern birds, though lost in extant crocodylians. The skull's low position suggests that Kentrosaurus may have been a browser of low-growing vegetation. This interpretation is supported by the absence of premaxillary teeth and their likely replacement by a horny beak or rhamphotheca. The presence of a beak extended along much of the jaws may have precluded the presence of cheeks in stegosaurs.[26] Due to its phylogenetic position, it is unlikely that Kentrosaurus had an extensive beak like Stegosaurus and it instead probably had a beak restricted to the jaw tips.[27][28] Other researchers have interpreted these ridges as modified versions of similar structures in other ornithischians which might have supported fleshy cheeks, rather than beaks.[7]

There are two nearly complete braincases known from Kentrosaurus though they exhibit some taphonomic distortion.[24] The frontals and parietals are flat and broad, with the latter bearing two transversely concave ventral sides with a ridge running down the middle that divides them. The lateral surface of the frontals form part of the orbit (eye socket) and the medial side creates the anterior part of the endocranial cavity (braincase). Basioccipitals (where the skull articulated with the cervical vertebrae) form the posterior floor of the brain and the occipital condyle, which is large and spherical in Kentrosaurus. The rest of the braincase is formed by the presphenoid composing the anterior end. The overall braincase morphology is very similar to those of Tuojiangosaurus, Huayangosaurus, and Stegosaurus. However, the occipital condyle is a closer distance to the basisphenoid tubera (bone at the front of the braincase) in Kentrosaurus and Huayangosaurus than in Tuojiangosaurus and some specimens of Stegosaurus. Due to dinosaurs having more molding in their braincases, endocasts of Kentrosaurus can be reconstructed using the preserved fossils. The brain is relatively short, deep, and small, with a strong cerebral and pontine flexures and a steeply inclined posterodorsal edge when compared to those of other ornithischians. There is a small dorsal projection in the endocast where an unossified (lacking bone) region between the top of the supraoccipital (bone at the top-back of the braincase) and overlying parietal that was likely covered in cartilage. This characteristic is seen in other ornithischians. Because of the prominent flexures, many of the aspects of the brain can only be interpreted by the present structures.[24]

In the mandible (lower jaw), only an incomplete right dentary is known from Kentrosaurus.[29] The deep dentary is almost identical in shape to that of Stegosaurus, albeit much smaller. Similarly, the tooth is a typical stegosaurian tooth, small with a widened base and vertical grooves creating five ridges. The dentary has 13 preserved alvelovi on the dorsomedial side and it they are slightly convex in lateral and dorsal views. On the surface adjacent to the alveoli, there is a shallow groove bearing small foramina (small openings in bone) that is similar to grooves on the dentary of the Cretaceous neornithischian Hypsilophodon, with one foramina per tooth position. Stegosaurian teeth were small, triangular, and flat; wear facets show that they did grind their food.[30] A single complete cheek tooth is preserved, with a large crown and long root. The crown notably has fewer marginal denticles and a prominent cingulum compared to Stegosaurus, Tuojiangosaurus, and Huayangosaurus.[24]

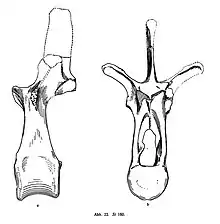

Postcrania

The neck was composed of 13 cervical (neck) vertebrae, the first being the atlas which was strongly fused to the occipital region of the skull and followed by the axis. The other 11 cervicals had hourglass-shaped centra (the base of a vertebra) and rounded ventral keels. The diapophyses are large and strongly angled posteriorily and parallel to each other. The spinous processes got larger towards the posterior end, while the postzygapophyses became smaller and less horizontal, giving the anterior part of the neck lots of mobility laterally. The dorsal column consists of 13 dorsal (back) vertebrae which are tall and have short centra. They have a neural arch more than twice as high as the centrum, the vertebral body, and almost completely occupied by the extremely spacious neural canal, a trait unique to Kentrosaurus. The diapophyses too were laterally elongated, creating a Y-shape in anterior view. The sacrum (part of pelvis with vertebrae) consists of 6 fused centra, the first being a loose sacrodorsal, while the rest of the centra's transverse processes (extensions of bone) are fused to the dorsal parts of the sacral ribs into a solid sacral plate. The ribs also fuse to the ilium (the upper part of the pelvis) creating a fully ankylosed and solid sacrum. The ilium is notable in that the preacetabular process, front blade, of the ilium widens laterally, to the front outer side, and does not taper unlike in all other stegosaurs. Another characteristic is that the length of the ilium equals, or is greater than, that of the thigh bone.[12] The caudal (tail) vertebrae are 29 in number, though 27-29 are coossified for attachment to the thagomizers (tail spikes). The caudal vertebrae are very unique, as they have a combination of transverse processes up to the 28th vertebra and rod-shaped processes on the posterior caudals. These posterior caudal processes have narrow bases that do not tough the plate formed by the fusion of the processes of the sacral vertebrae. Kentrosaurus can be distinguished from other members of the Stegosauria by a number of processes of the vertebrae, which in the tail do not run sub-parallel, as in most dinosaurs. In the front third of the tail, they point backwards, the usual direction. In the middle tail, however, they are almost vertical, and further back they are hook-shaped and point obliquely forward. The chevrons, bones pointing to below from the bottom side of the tail vertebrae, have the shape of an inverted T.[12]

.jpg.webp)

The scapula (shoulder blade) is sub-rectangular, with a robust blade. Though it is not always perfectly preserved, the acromion ridge is slightly smaller than in Stegosaurus. The blade is relatively straight, although it curves towards the back. There is a small bump on the back of the blade, that would have served as the base of the triceps muscle. The coracoid is sub-circular.[31] The fore limbs were much shorter than the stocky hind limbs, which resulted in an unusual posture. The humerus (upper arm bone), like other stegosaurs, has greatly expanded proximal and distal ends that were attachment points between the coracoid and ulna-radius (forearm bones) respectively. The radius was larger than the ulna and had a wedge-shaped proximal end. The manus (hand) was small and had five toes with 2 toes bearing only a single phalange. The hindlimbs were much larger and too are similar to those of other stegosaurs. The femur (thigh bone) is the longest element in the body, with the largest known femur measuring 665 mm from the proximal to distal end. The tibia (shin bone) was wide and robust, while the fibula was skinny and thin without a greatly expanded distal end. The pes (foot) terminated in 3 toes, all of which had hoof-like unguals (claws).[15][32][24]

Armour

Typically for a stegosaur, Kentrosaurus had extensive osteoderm (bony structures in the skin) covering, including small plates (probably located on the neck and anterior trunk), and spikes of various shapes. The spikes of Kentrosaurus are very elongated, with one specimen having a bone core length of 731 millimetres.[20] The plates have a thickened section in the middle, as if they were modified spines.[33] The spikes and plates were likely covered by horn. Aside from a few exceptions they were not found in close association with other skeletal remains. Thus, the exact position of most osteoderms is uncertain. A pair of closely spaced spikes was found articulated with a tail tip, and a number of spikes were found apparently regularly spaced in pairs along the path of an articulated tail.[13]

Hennig[13] and Janensch,[8] while grouping the dermal armour elements into four distinct types, recognised an apparently continuous change of shape among them, shorter and flatter plates at the front gradually merging into longer and more pointed spikes towards the rear, suggesting an uninterrupted distribution along the entire body, in fifteen pairs.[33] Because each type of osteoderm was found in mirrored left and right versions, it seems probable that all types of osteoderms were distributed in two rows along the back of the animal, a marked contrast to the better-known North American Stegosaurus, which had one row of plates on the neck, trunk and tail, and two rows of spikes on the tail tip. There is one type of spike that differs from all others in being strongly, and not only slightly, asymmetrical, and having a very broad base. Because of bone morphology classic reconstructions placed it on the hips, at the iliac blade, while many recent reconstructions place it on the shoulder, because a similarly shaped spike is known to have existed on the shoulder in the Chinese stegosaurs Gigantspinosaurus and Huayangosaurus.[33]

Classification and species

Like the spikes and shields of ankylosaurs, the bony plates and spines of stegosaurians evolved from the low-keeled osteoderms characteristic of basal thyreophorans.[34] Galton (2019) interpreted plates of an armored dinosaur from the Lower Jurassic (Sinemurian-Pliensbachian) Lower Kota Formation of India as fossils of a member of Ankylosauria; the author argued that this finding indicates a probable early Early Jurassic origin for both Ankylosauria and its sister group Stegosauria.[35]

The vast majority of stegosaurian dinosaurs thus far recovered belong to the Stegosauridae, which lived in the later part of the Jurassic and early Cretaceous, and which were defined by Paul Sereno as all stegosaurians more closely related to Stegosaurus than to Huayangosaurus.[36] This group is widespread, with members across the Northern Hemisphere, Africa and possibly South America.[37] The South American remains come from Chubut, Argentina and consist only of a partial humerus, but the anatomy of the humerus is very similar to that of Kentrosaurus and both date to the Late Jurassic. In a phylogenetic analysis, the Chubut stegosaurid was recovered in polytomy with Kentrosaurus as basal stegosaurids, further suggesting that they are closely related.[37]

In Hennig's 1915 description, Kentrosaurus was assigned to the family Stegosauridae due to the preservation of dermal armor and features like posterodorsally angled neural spines on the caudal vertebrae.[1] This is confirmed by modern cladistic analyses, although in 1915 Stegosauridae was a far more inclusive concept that included some taxa now classified as ankylosaurs. A consecutive narrowing down of this concept caused Kentrosaurus, until the 1980s to be seen as a typical "primitive" stegosaurian,[38] to be placed in a more derived, higher, position in the stegosaur evolutionary tree. However, recent analyses have consistently found Kentrosaurus to be in Stegosauridae, though typically as one of the most basal genera in the family.[39][37][40] Kentrosaurus has many traits not seen in other stegosaurids but seen in basal stegosaurians, such as the presence of a parascapular spine and maxillary teeth with only seven denticles at the margin.[17][41] Cladogram of Stegosauria below that includes nearly every known stegosaur genus, recovering Kentrosaurus as a basal stegosaurid:[40]

| Eurypoda |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The type and sole accepted species of Kentrosaurus is Kentrosaurus aethiopicus, named by Hennig in 1915. Fragmentary fossil material from Wyoming, named Stegosaurus longispinus by Charles Gilmore in 1914,[42] was in 1993 classified as a North American species of Kentrosaurus, as K. longispinus.[43] However, this action was not accepted by the paleontological community, and S. longispinus has been assigned to its own genus, Alcovasaurus, differing from Kentrosaurus in having more elongated tail spikes and the structure of the pelvis and vertebrae.[44][45] Cladogram of the phylogenetic analysis of Stegosauridae conducted by Maidment et al (2019), which recovers a distinct Alcovasaurus:[46]

| Stegosauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Feeding

Like all ornithischians, Kentrosaurus was a herbivore. The fodder was barely chewed and swallowed in large chunks. One hypothesis on stegosaurid diet holds that they were low-level browsers, eating foliage and low-growing fruit from various non-flowering plants.[47] Kentrosaurus was capable of eating at heights of up to 1.7 m (5 ft 7 in) when on all fours. It may also have been possible for it to rear up on its hindlegs to reach vegetation higher in trees.[9]

With its centre of mass close to the hind-limbs, the animal could potentially support itself as it stood up. The hips were likely capable of allowing a vertical trunk rotation of about 60 degrees and the tail probably would either have been fully lifted, not blocking this movement or have enough curvature to rest on the ground; thus it could have provided additional support, though precisely because of this flexibility it is not certain whether much support was actually provided: it was not stiff enough to function as a "third leg" as had been suggested by Robert Thomas Bakker. In this pose, Kentrosaurus could have fed at heights of 3.3 m (11 ft).[9]

Sexual dimorphism

Differences in the proportions, not the size, of the femurs (thighbones) led Holly Barden and Susannah Maidment to realize that Kentrosaurus probably showed sexual dimorphism. This dimorphism of the femurs consisted in them being either more or less robust than the other. The occurrence ratio of the robust morph to the gracile one was 2:1, and it is likely that the higher percentage of animals were females. Because of this ratio, it was considered reasonable to assume that in their society, Kentrosaurus males mated with more than one female, a behaviour also found in other vertebrates.[48]

The problem posed by the ratio is that the multiple specimens studied, died in the same place, but probably not in a sudden mass-death and so do not represent a single herd or contemporary population. The results may have been distorted by a greater chance for robust animals of getting fossilised or discovered. In an earlier study by Galton in 1982, it was suggested that individual difference in the sacral rib count of both Kentrosaurus and Dacentrurus might be an indication of dimorphism: females would have had an extra pair of sacral ribs, having also the first sacral vertebra connected to the ilium, in addition to the subsequent four sacrals.[48]

Reproduction and growth

As the plates and spikes would have been obstacles during copulation, it is possible that pairs mated back-to-back with the female staying still in a lordosis posture as the male maneuvers his penis into her cloaca. The shoulder spikes would have made the female unable to lie on her side during mating as is proposed for Stegosaurus.[49]

In 2013, a study by Ragna Redelstorff e.a. concluded that the bone histology of Kentrosaurus indicated that it had a higher growth rate than reported for Stegosaurus and Scutellosaurus, in view of the relatively rapid deposition of highly vascularised fibrolamellar bone. As Stegosaurus was larger than Kentrosaurus, this contradicts the general rule that larger dinosaurs grew quicker than smaller ones.[50]

Defence

Because the tail had at least forty caudal vertebrae,[13] it was highly mobile.[9] It could possibly swing at an arc of 180 degrees, covering the entire half circle behind it.[20][9] Swing speeds at the tail end may have been as high as 50 km/h. Continuous rapid swings would have allowed the spikes to slash open the skin of its attacker or to stab the soft tissues and break the ribs or facial bones. More directed blows would have resulted in the sides of the spikes fracturing even sturdy longbones of the legs by blunt trauma. These attacks would have crippled small and medium-sized theropods and may even have done some damage to large ones.[20] Earlier interpretations of the defensive behaviour of Kentrosaurus included the suggestion that the animal might have charged to the rear, to run through attackers with its spines, in the way of modern porcupines.[38]

Though Kentrosaurus likely stood with forelimbs erect like in other dinosaurs, it is hypothesised that the animal adopted a sprawling posture when defending itself. Its neck was flexible enough to allow it to keep sight of predators, as it could reach the sides of its body with its snout and look over the back. In addition, the posterior position of the center of mass may not have been advantageous for rapid locomotion, but meant that the animal could quickly rotate around the hips by pushing sideways with the arms, keeping the tail pointed at the attacker.[9] Kentrosaurus was nevertheless not invulnerable. A quick predator could have made it to the tail base (where the impact speed would be much lower) when the tail passed and the neck and upper-part of the body would have been unprotected by the tail swings. A successful predation of Kentrosaurus may have required group hunting. Compared to the more robust spikes of Stegosaurus, the thinner spikes of Kentrosaurus were at greater risk of bending.[20]

Paleoecology

Kentrosaurus lived in what is now Tanzania in the Late Jurassic Tendaguru Formation. The main Kentrosaurus quarries were located in the Middle Saurian Beds dating from the upper Kimmeridgian. Some remains were found in the Upper Saurian Beds dating from the Tithonian.[51] Since 2012, the boundary between the Kimmeridgian and Tithonian is dated at 152.1 million year ago.[52]

The Tendaguru ecosystem primarily consisted of three types of environment: shallow, lagoon-like marine environments, tidal flats and low coastal environments; and vegetated inland environments. The marine environment existed above the fair weather wave base and behind siliciclastic and ooid barriers. It appeared to have had little change in salinity levels and experienced tides and storms. The coastal environments consisted of brackish coastal lakes, ponds and pools. These environments had little vegetation and were probably visited by herbivorous dinosaurs mostly during droughts. The well vegetated inlands were dominated by conifers. Overall, the Late Jurassic Tendaguru climate was subtropical to tropical with seasonal rains and pronounced dry periods. During the Early Cretaceous, the Tendaguru became more humid.[53] The Tendaguru Beds are similar to the Morrison Formation of North America except in its marine interbeds.[54]

Kentrosaurus would have coexisted with fellow ornithischians like Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki; the sauropods Giraffatitan brancai, Dicraeosaurus hansemanni and D. sattleri, Janenschia africana, Tendaguria tanzaniensis and Tornieria africanus; theropods "Allosaurus" tendagurensis, "Ceratosaurus" roechlingi, "Ceratosaurus" ingens, Elaphrosaurus bambergi, Veterupristisaurus milneri and Ostafrikasaurus crassiserratus; and the pterosaur Tendaguripterus recki.[55][56][57][58] Other organisms that inhabited the Tendaguru included corals, echinoderms, cephalopods, bivalves, gastropods, decapods, sharks, neopterygian fish, crocodilians and small mammals like Brancatherulum tendagurensis.[59]

See also

Notes

- p. 223 in Paul (2010)[19]

References

- Hennig, E. (1915). "Kentrosaurus aethiopicus, der Stegosauride des Tendaguru [Kentrosaurus aethiopicus, the stegosaur of the Tendaguru]" (PDF). Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin. 1915: 219–247.

- Liddell, Henry George and Robert Scott (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged ed.). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-910207-5.

- Hennig, E. (1916). "Zweite Mitteilung über den Stegosauriden vom Tendaguru [Second report on the stegosaurid of the Tendaguru]". Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin (in German). 1916 (6): 175–182.

- Nopcsa, Baron. F. (1915). "Die Dinosaurier der Siebenbürgischen Landesteile Ungarns [The dinosaurs of the Siebenbürgen part of the Hungarian Empire]". Mitteilungen aus dem Jahrbuche der Königlich Ungarischen Geologischen Reichsanstalt (in German). 23: 1–26.

- Nopcsa, F. (1916). "Doryphorosaurus nov. nom. für Kentrosaurus HENNIG 1915". Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie. 1916: 511–512.

- Hennig, E. (1916). "Kentrurosaurus, non Doryphorosaurus". Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie (in German). 1916: 578.

- Galton PM, Upchurch P (2004). "Stegosauria". In Weishampel DB, Dodson P, Osmólska H (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- Janensch, W. (1925). "Ein aufgestelltes Skelett des Stegosauriers Kentrurosaurus aethiopicus HENNIG 1915 aus den Tendaguru-Schichten Deutsch-Ostafrikas [A mounted skeleton of the Stegosaur Kentrurosaurus aethiopicus HENNIG 1915 from the Tendaguru layers of German East Africa]". Palaeontographica. Supplement 7 (in German): 257–276.

- Mallison, H. (2010). "CAD assessment of the posture and range of motion of Kentrosaurus aethiopicus HENNIG 1915". Swiss Journal of Geosciences. 103 (2): 211–233. doi:10.1007/s00015-010-0024-2. S2CID 132746786.

- Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Kentrosaurus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 516–519. ISBN 978-0-89950-917-4.

- Galton, P.M. (1988). "Skull bones and endocranial casts of stegosaurian dinosaur Kentrosaurus HENNIG, 1915 from Upper Jurassic of Tanzania, East Africa". Geologica et Palaeontologica. 22: 123–143.

- Mallison, H. (2011). "The real lectotype of Kentrosaurus aethiopicus HENNIG 1915" (PDF). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie. 259 (2): 197–206. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2011/0114.

- Hennig, E. (1925). "Kentrurosaurus aethiopicus. Die Stegosaurier-Funde vom Tendaguru, Deutsch-Ostafrika [Kentrurosaurus aethiopicus. The Stegosaur find from Tendaguru, German East-Africa]". Palaeontographica. Supplement 7 (in German): 101–254.

- Maier, G (2003). African Dinosaurs Unearthed. The Tendaguru Expeditions. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 432. ISBN 978-0-253-34214-0.

- Hennig, E. (1925). Kentrurosaurus aethiopicus; die Stegosaurierfunde vom Tendaguru, Deutsch-Ostafrika. Palaeontographica-Supplementbände, 101-254.

- Janensch, W. (1925). Ein aufgestelltes skelett des stegosauriers Kentrurosaurus aethiopicus E. Hennig aus den Tendaguru-schichten Deutsch-Ostafrikas. Palaeontographica-Supplementbände, 255-276.

- Galton, P.M. (1982). "The postcranial anatomy of stegosaurian dinosaur Kentrosaurus from the Upper Jurassic of Tanzania, East Africa". Geologica et Palaeontologica. 15: 139–165.

- Mallison, H. (2011). The real lectotype of Kentrosaurus aethiopicus HENNIG, 1915. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie-Abhandlungen, 197-206.

- Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press

- Mallison, H. (2011). "Defense capabilities of Kentrosaurus aethiopicus HENNIG 1915". Palaeontologia Electronica. 14 (2): 10.

- Benson, Roger B. J.; Campione, Nicolás E.; Carrano, Matthew T.; Mannion, Philip D.; Sullivan, Corwin; Upchurch, Paul; Evans, David C. (2014-05-06). "Rates of Dinosaur Body Mass Evolution Indicate 170 Million Years of Sustained Ecological Innovation on the Avian Stem Lineage". PLOS Biology. 12 (5): e1001853. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001853. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 4011683. PMID 24802911.

- Woodruff, D.C.; Trexler, D.; Maidment, S.C.R. (2019). "Two New Stegosaur Specimens from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Montana, USA". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 64 (3): 461–480. doi:10.4202/app.00585.2018. S2CID 201310639.

- Mallison, H. (2014-03-07). "Osteoderm distribution has low impact on the centre of mass of stegosaurs". Fossil Record. 17 (1): 33–39. doi:10.5194/fr-17-33-2014. ISSN 2193-0066.

- Galton, P. M. (1988). Skull bones and endocranial casts of stegosaurian dinosaur Kentrosaurus Hennig, 1915 from Upper Jurassic of Tanzania, East Africa. Geologica et Palaeontologica, 22, 123-143.

- Maidment, S. C., Norman, D. B., Barrett, P. M., & Upchurch, P. (2008). Systematics and phylogeny of Stegosauria (Dinosauria: Ornithischia). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 6(4), 367-407.

- Czerkas, S (1999). "The beaked jaws of stegosaurs and their implications for other ornithischians". Miscellaneous Publication of the Utah Geological Survey. 99–1: 143–150.

- Knoll, F (2008). "Buccal soft anatomy in Lesothosaurus (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)" (PDF). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 248 (3): 355–364. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2008/0248-0355.

- Barrett, P.M. (2001). Tooth wear and possible jaw action of Scelidosaurus harrisonii Owen and a review of feeding mechanisms in other thyreophoran dinosaurs. Pp. 25-52 in Carpenter, K. (ed.): The Armored Dinosaurs. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Hennig, E. (1936). Ein dentale von Kentrurosaurus aethiopicus Hennig. Palaeontographica-Supplementbände, 309-312.

- Fastovsky DE, Weishampel DB (2005). "Stegosauria: Hot Plates". In Fastovsky DE, Weishampel DB (eds.). The Evolution and Extinction of the Dinosaurs (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 107–30. ISBN 978-0-521-81172-9.

- Maidment, Susannah Catherine Rose; Brassey, Charlotte; Barrett, Paul Michael (2015-10-14). "The Postcranial Skeleton of an Exceptionally Complete Individual of the Plated Dinosaur Stegosaurus stenops (Dinosauria: Thyreophora) from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Wyoming, U.S.A." PLOS ONE. 10 (10): e0138352. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1038352M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138352. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4605687. PMID 26466098.

- Galton, P. M. (1982). The postcranial anatomy of stegosaurian dinosaur Kentrosaurus from the Upper Jurassic of Tanzania, East Africa.

- Galton, P.M., and P. Upchurch, 2004, "Stegosauria", pp. 343–362 in: D.B. Weishampel, P. Dodson, and H. Osmolska (eds.), The Dinosauria, 2nd Edition. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

- Norman, David (2001). "Scelidosaurus, the earliest complete dinosaur" in The Armored Dinosaurs, pp 3-24. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33964-2.

- Peter M. Galton (2019). "Earliest record of an ankylosaurian dinosaur (Ornithischia: Thyreophora): Dermal armor from Lower Kota Formation (Lower Jurassic) of India". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 291 (2): 205–219. doi:10.1127/njgpa/2019/0800. S2CID 134302379.

- Sereno, P.C., 1998, "A rationale for phylogenetic definitions, with application to the higher-level taxonomy of Dinosauria", Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 210: 41-83

- Rauhut, Oliver W. M.; Carballido, José Luis; Pol, Diego (2020-12-10). "First osteological record of a stegosaur (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the Upper Jurassic of South America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 40 (6): e1862133. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1862133. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 234161169.

- Norman, D.B., 1985, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs, Salamander Books Ltd, London

- Hui, Dai; Ning, Li; Maidment, Susannah C. R.; Guangbiao, Wei; Yuxuan, Zhou; Xufeng, Hu; Qingyu, Ma; Xunqian, Wang; Haiqian, Hu; Guangzhao, Peng (2022-03-30). "New stegosaurs from the Middle Jurassic Lower Member of the Shaximiao Formation of Chongqing, China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 41 (5): e1995737. doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.1995737. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 247267743.

- Raven, Thomas J.; Maidment, Susannah C. R. (2017). "A new phylogeny of Stegosauria (Dinosauria, Ornithischia)". Palaeontology. 60 (3): 401–408. doi:10.1111/pala.12291. hdl:10044/1/45349. S2CID 55613546.

- Galton, P.M., 1990, "Stegosauria", in: D.B. Weishampel, P. Dodson, & H. Osmólska (eds.), The Dinosauria. University of California Press, pp. 435–455

- Gilmore, C.W. (1914). "Osteology of the armored Dinosauria in the United States National Museum, with special reference to the genus Stegosaurus". United States National Museum Bulletin. 81: 1–136. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.63658.

- Olshevsky, G.; Ford, T.L. (1993). "The Origin and Evolution of the Stegosaurs". Kyoryugaku Saizensen. 4: 64–103.

- Ulansky, R. E., 2014. Evolution of the stegosaurs (Dinosauria; Ornithischia). Dinologia, 35 pp. [in Russian]. [DOWNLOAD PDF] http://dinoweb.narod.ru/Ulansky_2014_Stegosaurs_evolution.pdf.

- Ulansky, RE, 2014. Natronasaurus longispinus, 100 years with another name. Dinologia, 10 pp. [In Russian].

- Maidment, Susannah C. R.; Raven, Thomas J.; Ouarhache, Driss; Barrett, Paul M. (2020-01-01). "North Africa's first stegosaur: Implications for Gondwanan thyreophoran dinosaur diversity". Gondwana Research. 77: 82–97. Bibcode:2020GondR..77...82M. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2019.07.007. hdl:10141/622706. ISSN 1342-937X. S2CID 202188261.

- Weishampel DB (1984). "Interactions between Mesozoic Plants and Vertebrates: Fructifications and seed predation". N. Jb. Geol. Paläontol. Abhandl. 167: 224–250.

- Barden, H.E.; Maidment, S.C.R. (2011). "Evidence for sexual dimorphism in the stegosaurian dinosaur Kentrosaurus aethiopicus from the Upper Jurassic of Tanzania". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (3): 641–651. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.557112. S2CID 83521877.

- Isles, T. (2009). "The socio-sexual behaviour of extant archosaurs: Implications for understanding dinosaur behaviour" (PDF). Historical Biology. 21 (3–4): 139–214. doi:10.1080/08912960903450505. S2CID 85417112.

- Ragna Redelstorff; Tom R. Hübner; Anusuya Chinsamy; P. Martin Sander (2013). "Bone histology of the stegosaur Kentrosaurus aethiopicus (Ornithischia: Thyreophora) from the Upper Jurassic of Tanzania". The Anatomical Record. 296 (6): 933–952. doi:10.1002/ar.22701. PMID 23613282. S2CID 23433029.

- Robert Bussert, Wolf-Dieter Heinrich and Martin Aberhan, 2009, "The Tendaguru Formation (Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous, southern Tanzania): definition, palaeoenvironments, and sequence stratigraphy", Fossil Record 12(2) 2009: 141–174

- Gradstein, F.M.; Ogg, J.G.; Schmitz, M.D. & Ogg, G.M., 2012, A Geologic Time Scale 2012, Elsevier

- Aberhan, Martin; Bussert, Robert; Heinrich, Wolf-Dieter; Schrank, Eckhart; Schultka, Stephan; Sames, Benjamin; Kriwet, Jürgen; Kapilima, Saidi (2002). "Palaeoecology and depositional environments of the Tendaguru Beds (Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous, Tanzania)". Fossil Record. 5 (1): 19–44. doi:10.1002/mmng.20020050103.

- Mateus, Octávio (2006). "Late Jurassic dinosaurs from the Morrison Formation (USA), the Lourinhā and Alcobaça formations (Portugal), and the Tendaguru Beds (Tanzania): a comparison". In Foster, J.R.; Lucas, S.G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Morrison Formation. pp. 223–232. ISSN 1524-4156.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Weishampel, David B; et al. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution (Late Jurassic, Africa)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 552. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- Barrett, P.M., Butler, R.J., Edwards, N.P., & Milner, A.R. Pterosaur distribution in time and space: an atlas. p61–107. in Flugsaurier: Pterosaur papers in honour of Peter Wellnhofer. 2008. Hone, D.W.E., and Buffetaut, E. (eds). Zitteliana B, 28. 264pp.

- Rauhut, Oliver W. M. (2011). "Theropod dinosaurs from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru (Tanzania)". Special Papers in Palaeontology. 86: 195–239.

- Buffetaut, Eric (2012). "An early spinosaurid dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru (Tanzania) and the evolution of the spinosaurid dentition". Oryctos. 10: 1–8.

- Heinrich, Wolf-Dieter; et al. (2001). "The German‐Tanzanian Tendaguru Expedition 2000". Fossil Record. 4 (1): 223–237. doi:10.1002/mmng.20010040113.

External links

- Stegosauria from Thescelosaurus.com (Includes details on Kentrosaurus, its junior synonyms, and other material)