Cayor

Cayor (Wolof: Kajoor; Arabic: كاجور) was from 1549 to 1876 the largest and most powerful kingdom that split off from the Jolof Empire in what is now Senegal. Cayor was located in northern and central Senegal, southeast of Walo, west of the kingdom of Jolof, and north of Baol and the Kingdom of Sine.

Kingdom of Cayor Kajoor | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1549–1879 | |||||||||

Reconstructed flag | |||||||||

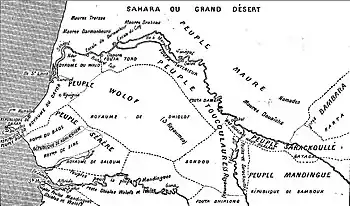

Senegalese states c. 1850. Cayor is at left, center | |||||||||

| Status | Kingdom | ||||||||

| Capital | Mboul (traditional) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Wolof | ||||||||

| Religion | African traditional religions, Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Damel | |||||||||

• 1549 – ? | Dece Fu Njogu (first) | ||||||||

• 1879 | Samba Laube Fal (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | Cayor defeats Jolof at Battle of Danki 1549 | ||||||||

• Sporadically in personal union with Baol | 1555–1874 | ||||||||

• French colonization | 1879 | ||||||||

| Currency | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Etymology

Cayor (also spelled Kayor, Kadior, Cadior, Kadjoor, Nkadyur, Kadyoor, Encalhor, among others) comes from the Wolof endonym for the inhabitants "Waadyor" meaning "people of the arid lands." This distinguishes the people of Cayor from their neighbors, who to the present day refer to themselves by doubling the name of their native region (Waalo-Waalo, Saloum-Saloum e.g.).[1]

History

In 1549, the damel (dammeel in Wolof,[2] often translated into European languages as "king") Dece Fu Njogu became independent from Jolof and set Cayor's capital at Mboul.

During the Char Bouba War in the late 17th century, Damel Detye Maram was overthrown by an alliance between a lingeer and the marabouts of Cayor. When the new damel failed to follow Islam, however, he in turn was killed and the ruling class sought Saloum's support against drive out the marabouts.[3] When the Islamic movement's leader Nasr al-Din was killed in battle in 1674, the old aristocracy reasserted themselves but had been weakened.

In 1693 the aristocracy, now threatened by the Buur of Saloum, appealed to the Teigne of neighboring Baol, Lat Sukaabe Fall for help. He took over Cayor and declared himself the Damel-Teigne, imposing the hegemony of his material line, the Geej, over the previously dominant Dorobe and Guelwaar. He also strengthened central power, coopted the marabouts with royal appointments, and frequently clashed with the French over their attempts to impose a trade monopoly on the kingdom.[4]

In 1776, inspired by the rise of the Imamate of Futa Toro, the marabouts again rose up against Damel Amari Ngoone Ndela Kumba but were defeated and sold into slavery. Soon after, Almamy Abdul Kader invaded but was defeated at the battle of Bunxoy. Abdulkader was captured, but the damel soon released him.[5]: 95 The surviving marabouts played an important role in founding the Lebou republic on the Cap-Vert peninsula.[1]

During the 18th century, under the leadershup of Damel Maïsa Teindde Ouédji, Cayor annexed the Kingdom of Baol but was then embroiled in a succession dispute after his death. Baol regained its independence in 1756.[6]

Lat Jor and Resistance to the French

In 1859 a rebellion broke out in the province of Ndiambour led by prominent marabout leaders and the pretender Ma-Dyodyo Fall attempting to overthrow the ruling Geej dynasty, but was quickly crushed.[7] When the new damel did not agree to French commercial demands,[8] in 1861 they installed Ma-Dyodyo in power, sparking a backlash among the nobility led by Lat Jor. After some initial military success in 1863, early the next year French troops forced Lat Jor to take refuge with the almaami of Saloum, Maba Diakhou Ba.[9][10]

The French attempted to annex the country, but this ultimately proved unworkable.[11] In 1868 Lat Jor and his troops returned to Cayor to attempt to regain independence. He allied with Shaikh Amadou Ba and defeated the French in the battle of Mekhe on July 8th, 1869.[12] By 1871 the French accepted his restoration to the position of damel. Amadou Ba's interventions in Cayor soon ended their alliance. [13] Over the next few years Lat Jor tried to exert his authority over Baol and helped the French defeat and kill Amadou in 1875.[14]

This alliance was broken in 1881 when Lat Jor began a rebellion to resist the construction of the Dakar to Saint-Louis railway across Cayor. Dior is reported to have told the French Governor Servatius:

"As long as I live, be assured, I shall oppose, with all my might the construction of this railway."[15]

The Governor installed one of Lat Jor's nephews Samba Laube Fal (1858–1886) in his place as Damel in 1883, but his rule lasted only three years before he was murdered by a French lieutenant in Tivaouane on October 6, 1886. Lat Jor died in battle soon afterwards, and the kingdom of Cayor ceased to exist as an independent, united state.[16]

Government

In addition to Cayor, the damels also ruled over the Lebou area of Cap-Vert (where modern Dakar is), and they often ruled as the "Teignes" (rulers) of the neighboring kingdom of Baol.

Traditionally the damel himself was not purely hereditary, but was designated by a 4-member council consisting of:

- the Jaudin Bul (Diawdine-Boul), hereditary chief of the Jambur ("free men"; French Diambour)

- the Calau (Tchialaw), chief of the canton of Jambanyan (Diambagnane)

- the Botal (Bôtale), chief of the canton of Jop (Diop), and

- the Baje (Badgié), chief of the canton of Gateny (Gatègne).

Culture

Cayor society was highly stratified. The damel and nobles (Garmi) were at the top of the hierarchy followed by free men (including villagers and marabouts) who were known as Jambur. Below the Jambur were the Nyenoo, members of hereditary and endogamous castes that were metalworkers, tailors, griots, woodcarvers, etc. The lowest group of the hierarchy consisted of Dyaam, or slaves. Slaves were generally treated well and those that were owned by the kingdom often exercised military and political power.[17]

The Tyeddo class were warriors generally recruited among the slaves of the damel. Fiercely opposed to Islam, they were renowned drinkers, brave fighters, and inveterate raiders. Their depredations went a long way to creating unrest and promoting Islam among the population.[1]

As early as the 15th century, rulers were exposed to Islamic influence. In 1445, Venetian traveler Alvise Cadamosto reported that the king's entourage included Berber and Arab clerics.[18] Since at least the 16th century, traces of Islamic influence were felt in the kingdom and in certain rituals among the nobility. Literate marabouts settled in the area from Mali or Fouta. With the conversion of Lat Jor to Islam, the inhabitants began to quickly adopt the religion as well.[19]

List of rulers

Names and dates taken from John Stewart's African States and Rulers (1989).[20]

- Detye Fu-N'diogu (1549)

- Amari Fall (1549-1593)

- Samba Fall(1593-1600)

- Khuredya Fall (1600-1610)

- Biram Manga Fall (1610-1640)

- Dauda Demba Fall (1640-1647)

- Dyor Fall (1647-1664)

- Birayma Yaasin-Bubu Fall (1664–1681)

- Detye Maram N'Galgu Fall (1681–1683)

- Faly Fall (1683–1684)

- Khuredya Kumba Fall (1684–1691)

- Birayma Mbenda-Tyilor Fall (1691–1693)

- Dyakhere Fall (1693)

- Dethialaw Fall (1693–1697)

- Lat Sukaabe Fall (1697–1719)

- Isa-Tende Fall (1719–1748)

- Isa Bige N'Gone Fall (1758–1759) (First Reign)

- Birayma Yamb Fall (1759–1760)

- Isa Bige N'Gone Fall (1760–1763) (Second Reign)

- Dyor Yaasin Isa Fall (1763–1766)

- Kodu Kumba Fall (1766–1777)

- Birayama Faatim-Penda Fall (1777–1790)

- Amari Fall (1790–1809)

- Birayama Fatma Fall (1809–1832)

- Isa Ten-Dyor Fall (1832–1855)

- Birayama-Fall (1855–1859)

- Ma-Kodu Fall (1859 – May 1861)

- Ma-Dyodyo Fall (May 1861 – December 1861) (First Reign)

- Lat-Dyor Diop (1862 – December 1863) (First Reign)

- Ma-Dyodyo Fall (January 1864 – 1868) (Second Reign)

- Lat-Dyor Diop (1868 – December 1872) (Second Reign)

- Amari Fall (January 1883 – August 1883)

- Samba Fall (1883–1886)

References

- Monteil 1963, p. 78.

- Papa Samba Diop, Glossaire du roman sénégalais, L'Harmattan, Paris, 2010, p. 140-143

- Barry 1998, p. 52.

- Barry 1998, p. 82-3.

- Boulègue, Jean (1999). "Conflit politique et identité au Sénégal : la bataille de Bunxoy (c. 1796)". Histoire d'Afrique : les enjeux de mémoire (in French). Paris: Karthala. p. 93-99.

- Barry, Boubacar (1972). Le royaume du Waalo: le Senegal avant la conquete. Paris: Francois Maspero. p. 195-6.

- Searing 2002, p. 32.

- Searing 2002, p. 38.

- Monteil 1963, p. 91.

- Lewis 2022, p. 57-58.

- Charles 1977, pp. 55.

- Gaye, Khalifa Babacar. "AUJOURD'HUI : 8 juillet 1869, Lat-Dior et Cheikhou Amadou Ba remportent la bataille de Mékhé". Sene News. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- Charles 1977, pp. 74.

- Charles 1977, pp. 78.

- BBC. The Story of Africa: Railways.

- Monteil 1963, p. 92-93.

- Lewis 2017, p. 167-8.

- Mota, Thiago H. (2021). "Wolof and Mandinga Muslims in the early Atlantic World: African background, missionary disputes, and social expansion of Islam before the Fulani jihads". Atlantic Studies. 20: 150–176. doi:10.1080/14788810.2021.2000835. ISSN 1478-8810. S2CID 244052915.

- Lewis 2017, p. 167, 172.

- Stewart, John (1989). African States and Rulers. London: McFarland. p. 150. ISBN 0-89950-390-X.

Sources

- Barry, Boubacar (1998). Senegambia and the Atlantic slave trade. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Charles, Eunice A. (1977). Precolonial Senegal : the Jolof Kingdom, 1800-1890. Brookline, MA: African Studies Center, Boston University. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- Lewis, Jori (2022). Slaves for Peanuts: A Story of Conquest, Liberation, and a Crop That Changed History. The New Press. ISBN 978-1-62097-156-7.

- Lewis, I. M. (2017). Islam in Tropical Africa. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-138-23275-4.

- Monteil, Vincent (1963). "Lat-Dior, damel du Kayor (1842-1886) et l'islamisation des Wolofs". Archives de Sociologie Des Religions. 8 (16): 77–104. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- Searing, James F. (2002). "God alone is king" : Islam and emancipation in Senegal : the Wolof kingdoms of Kajoor and Bawol, 1859-1914. NH: Heinemann. Retrieved 15 July 2023.