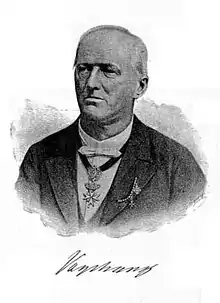

Karl Freiherr von Vogelsang

Karl Freiherr von Vogelsang (3 September 1818 – 8 November 1890), a journalist, politician and Catholic social reformer, was one of the mentors of the Christian Social movement in Austria-Hungary.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Austria |

|---|

|

Life

He was born in Liegnitz in the Silesia Province of Prussia (present-day Legnica, Poland), studied jurisprudence at Bonn, Rostock and Berlin, and settled at his family's estate Alt-Guthendorf near Marlow in Mecklenburg-Schwerin. After the Revolutions of 1848 Vogelsang moved to Berlin, where he made the acquaintance of Wilhelm Emmanuel Freiherr von Ketteler and Friedrich Maassen. Like Maassen he converted to Catholicism in 1850,[1] whereafter he had to resign as deputy to the Protestant Mecklenburg Landtag. Vogelsang then worked as a journalist in Catholic Southern Germany and spent several years in Munich, where he wrote for periodical publications established by the circles around Guido Görres. From 1859 he accompanied Prince Johann II of Liechtenstein on his voyages throughout Europe.

Vogelsang finally settled in Austria in 1864. In 1875, he became editor of the Catholic newspaper Das Vaterland ("The Native Country") edited by Leo von Thun-Hohenstein. This conservative publication was highly influential on Catholic social teaching, helping to establish the 40-hour work week and national health insurance for workers under the government of Minister-President Eduard Taaffe. Vogelsang died at Vienna in 1890, aged 72. Many of his thoughts found entrance into the 1891 Rerum novarum encyclical issued by Pope Leo XIII. As a social reformer, he was later seen as a precursor by the Austrofascist authoritarian state of the 1930s; he was quoted in the regime's propaganda by its leader, Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss.

Antisemitism

Vogelsang was the initiator of the rising Christian people's movement in Austria and in some neighboring countries. Since some former members of the antisemitic people's movement of Georg Ritter von Schönerer (for example the Viennese mayor Karl Lueger) joined Vogelsang, some authors call Vogelsang an antisemite too. But Vogelsang said as well that Christians not only should pray to God but also do good works for the poor so as to be God's people on the side of the Jews, His first chosen and forever beloved people.

However, some of Vogelsang's pronouncedly disfavourable remarks about Jews related to his anti-liberal and anti-capitalist views were included by his admirer, the once Austrofascist and later European federalist who survived the Buchenwald concentration camp, Eugen Kogon, in a volume entitled "Catholic-Conservative Heritage" which called for the establishment of a Catholic Third Reich and was edited by the Benedictine abbot of Maria Laach, Ildefons Herwegen, in 1934, to be distributed to a large share of Catholic households in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland by the Herder publishing house.

Many of the people who gathered into Vogelsang's movement, established the Christian Social Party in 1893, and some successors like Anton Orel developed strong antisemitic views. Another group of followers like Karl Lugmayer, Irene Harand, Pater Cyrill Fischer, Ernst Karl Winter (Sociologist and Vice-mayor of Vienna, who in 1938 emigrated to USA), Alfred Missong and Hildegard Burjan, understood Vogelsang's thoughts as laying stress on social questions. They, like some other Christians, strained to help the poor and to establish new social laws, but they also tried to change people's minds and to help persecuted Jews, Karl before and during the Nazi period.

References

- Rogers, Kara (August 30, 2018). "Karl, Freiherr von Vogelsang". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved September 26, 2018.