Ancient Mesopotamian underworld

The ancient Mesopotamian underworld, most often known in Sumerian as Kur, Irkalla, Kukku, Arali, or Kigal and in Akkadian as Erṣetu, although it had many names in both languages, was a dark, dreary cavern located deep below the ground,[1][2] where inhabitants were believed to continue "a transpositional version of life on earth".[1] The only food or drink was dry dust, but family members of the deceased would pour sacred mineral libations from the earth for them to drink. In the Sumerian underworld, it was initially believed that there was no final judgement of the deceased and the dead were neither punished nor rewarded for their deeds in life.

The ruler of the underworld was the goddess Ereshkigal, who lived in the palace Ganzir, sometimes used as a name for the underworld itself. Her husband was either Gugalanna, the "canal-inspector of Anu", or, especially in later stories, Nergal, the god of war. After the Akkadian Period (c. 2334–2154 BC), Nergal sometimes took over the role as ruler of the underworld. The seven gates of the underworld are guarded by a gatekeeper, who is named Neti in Sumerian. The god Namtar acts as Ereshkigal's sukkal, or divine attendant. The dying god Dumuzid spends half the year in the underworld, while, during the other half, his place is taken by his sister, the scribal goddess Geshtinanna, who records the names of the deceased. The underworld was also the abode of various demons, including the hideous child-devourer Lamashtu, the fearsome wind demon and protector god Pazuzu, and galla, who dragged mortals to the underworld.

Names

The Sumerians had a large number of different names which they applied to the underworld, including Arali, Irkalla, Kukku, Kur, Kigal, and Ganzir.[3] All of these terms were later borrowed into Akkadian.[3] The rest of the time, the underworld was simply known by words meaning "earth" or "ground", including the terms Kur and Ki in Sumerian and the word erṣetu in Akkadian.[3] When used in reference to the underworld, the word Kur usually means "ground",[3][4][lower-alpha 1] but sometimes this meaning is conflated with another possible meaning of the word Kur as "mountain".[3] The cuneiform sign for Kur was written ideographically with the cuneiform sign 𒆳, a pictograph of a mountain.[7] Sometimes the underworld is called the "land of no return", the "desert", or the "lower world".[3] The most common name for the earth and the underworld in Akkadian is erṣetu,[8] but other names for the underworld include: ammatu, arali / arallû, bīt ddumuzi ("House of Dumuzi"), danninu, erṣetu la târi ("Earth of No Return"), ganzer / kanisurra, ḫaštu, irkalla, kiūru, kukkû ("Darkness"), kurnugû ("Earth of No Return"), lammu, mātu šaplītu, and qaqqaru.[8] In the myth "Nergal and Ereshkigal" it is also referred to as Kurnugi.[9]

Conditions

All souls went to the same afterlife,[1][3] and a person's actions during life had no effect on how the person would be treated in the world to come.[1] Unlike in the ancient Egyptian afterlife, there was no process of judgement or evaluation for the deceased;[3] they merely appeared before Ereshkigal, who would pronounce them dead,[3] and their names would be recorded by the scribal goddess Geshtinanna.[3] The souls in Kur were believed to eat nothing but dry dust[11] and family members of the deceased would ritually pour libations into the dead person's grave through a clay pipe, thereby allowing the dead to drink.[12] For this reason, it was considered essential to have as many offspring as possible so that one's descendants could continue to provide libations for the dead person to drink for many years.[13] Those who had died without descendants would suffer the most in the underworld, because they would have nothing to drink at all,[14] and were believed to haunt the living.[15] Sometimes the dead are described as naked or clothed in feathers like birds.[3]

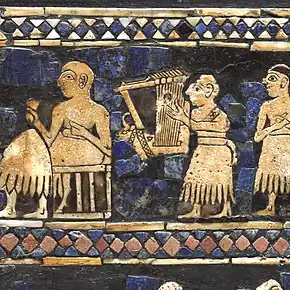

Nonetheless, there are assumptions according to which treasures in wealthy graves had been intended as offerings for Utu and the Anunnaki, so that the deceased would receive special favors in the underworld.[2] During the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112 – c. 2004 BC), it was believed that a person's treatment in the afterlife depended on how they were buried;[12] those that had been given sumptuous burials would be treated well,[12] but those who had been given poor burials would fare poorly.[12] Those who did not receive a proper burial, such as those who had died in fires and whose bodies had been burned or those who died alone in the desert, would have no existence in the underworld at all, but would simply cease to exist.[14] The Sumerians believed that, for the highly privileged, music could alleviate the bleak conditions of the underworld.[10]

Geography

A staircase led down to the gates of the underworld.[3] The underworld itself is usually located even deeper below ground than the Abzu, the body of freshwater which the ancient Mesopotamians believed lay deep beneath the earth.[3] In other, conflicting traditions, however, it seems to be located at a remote and inaccessible location on earth, possibly somewhere in the far west.[3] This alternate tradition is hinted at by the fact that the underworld is sometimes called "desert"[3] and by the fact that actual rivers located far away from Sumer are sometimes referred to as the "river of the underworld".[3] The underworld was believed to have seven gates, through which a soul needed to pass.[1] All seven gates were protected by bolts.[16] The god Neti was the gatekeeper.[17][18] Ereshkigal's sukkal, or messenger, was the god Namtar.[19][17] The palace of Ereshkigal was known as Ganzir.[16]

At night, the sun-god Utu was believed to travel through the underworld as he journeyed to the east in preparation for the sunrise.[20] One Sumerian literary work refers to Utu illuminating the underworld and dispensing judgement there[21] and Shamash Hymn 31 (BWL 126) states that Utu serves as a judge of the dead in the underworld alongside the malku, kusu, and the Anunnaki.[21] On his way through the underworld, Utu was believed to pass through the garden of the sun-god,[20] which contained trees that bore precious gems as fruit.[20] The Sumerian hymn Inanna and Utu contains an etiological myth in which Utu's sister Inanna begs her brother Utu to take her to Kur,[22] so that she may taste the fruit of a tree that grows there,[22] which will reveal to her all the secrets of sex.[22] Utu complies and, in Kur, Inanna tastes the fruit and becomes knowledgeable of sex.[22]

Inhabitants

Ereshkigal and family

A number of deities were believed by the ancient Mesopotamians to reside in the underworld.[3] The queen of the underworld was the goddess Ereshkigal.[16][17][1] She was believed to live in a palace known as Ganzir.[16] In earlier stories, her husband is Gugalanna,[16] but, in later myths, her husband is the god Nergal.[16][17] Her gatekeeper was the god Neti[17] and her sukkal is the god Namtar.[16] In the poem Inanna's Descent into the Underworld, Ereshkigal is described as Inanna's "older sister".[23]

Gugalanna is the first husband of Ereshkigal, the queen of the underworld.[16] His name probably originally meant "canal inspector of An"[16] and he may be merely an alternative name for Ennugi.[16] The son of Ereshkigal and Gugalanna is Ninazu.[16] In Inanna's Descent into the Underworld, Inanna tells the gatekeeper Neti that she is descending to the underworld to attend the funeral of "Gugalanna, the husband of my elder sister Ereshkigal".[16][24][23]

During the Akkadian Period (c. 2334 – 2154 BC), Ereshkigal's role as the ruler of the underworld was assigned to Nergal, the god of death.[1][17] The Akkadians attempted to harmonize this dual rulership of the underworld by making Nergal Ereshkigal's husband.[1] Nergal is the deity most often identified as Ereshkigal's husband.[25] He was also associated with forest fires (and identified with the fire-god, Gibil[26]), fevers, plagues, and war.[25] In myths, he causes destruction and devastation.[25]

Ninazu is the son of Ereshkigal and the father of Ningishzida.[27] He is closely associated with the underworld.[27] He was mostly worshipped in Eshnunna during the third millennium BC, but he was later supplanted by the Hurrian storm god Tishpak.[27] A god named "Ninazu" was also worshipped at Enegi in southern Sumer,[27] but this may be a different local god by the same name.[27] His divine beast was the mušḫuššu, a kind of dragon, which was later given to Tishpak and then Marduk.[27]

Ningishzida is a god who normally lives in the underworld.[28] He is the son of Ninazu and his name may be etymologically derived from a phrase meaning "Lord of the Good Tree".[28] In the Sumerian poem, The Death of Gilgamesh, the hero Gilgamesh dies and meets Ningishzida, along with Dumuzid, in the underworld.[29] Gudea, the Sumerian king of the city-state of Lagash, revered Ningishzida as his personal protector.[29] In the myth of Adapa, Dumuzid and Ningishzida are described as guarding the gates of the highest Heaven.[30] Ningishzida was associated with the constellation Hydra.[31]

Other underworld deities

Dumuzid, later known by the corrupted form Tammuz, is the ancient Mesopotamian god of shepherds[32] and the primary consort of the goddess Inanna.[32] His sister is the goddess Geshtinanna.[32][33] In addition to being the god of shepherds, Dumuzid was also an agricultural deity associated with the growth of plants.[34][35] Ancient Near Eastern peoples associated Dumuzid with the springtime, when the land was fertile and abundant,[34][36] but, during the summer months, when the land was dry and barren, it was thought that Dumuzid had "died".[34][37] During the month of Dumuzid, which fell in the middle of summer, people all across Sumer would mourn over his death.[38][39] An enormous number of popular stories circulated throughout the Near East surrounding his death.[38][39]

Geshtinanna is a rural agricultural goddess sometimes associated with dream interpretation.[40] She is the sister of Dumuzid, the god of shepherds.[40] In one story, she protects her brother when the galla demons come to drag him down to the underworld by hiding him successively in four different places.[40] In another version of the story, she refuses to tell the galla where he is hiding, even after they torture her.[40] The galla eventually take Dumuzid away after he is betrayed by an unnamed "friend",[40] but Inanna decrees that he and Geshtinanna will alternate places every six months, each spending half the year in the underworld while the other stays in Heaven.[40] While she is in the underworld, Geshtinanna serves as Ereshkigal's scribe.[40]

Lugal-irra and Meslamta-ea are a set of twin gods who were worshipped in the village of Kisiga, located in northern Babylonia.[41] They were regarded as guardians of doorways[42] and they may have originally been envisioned as a set of twins guarding the gates of the underworld, who chopped the dead into pieces as they passed through the gates.[43] During the Neo-Assyrian Period (911 BC–609 BC), small depictions of them would be buried at entrances,[42] with Lugal-irra always on the left and Meslamta-ea always on the right.[42] They are identical and are shown wearing horned caps and each holding an axe and a mace.[42] They are identified with the constellation Gemini, which is named after them.[42]

Neti is the gatekeeper of the underworld.[44] In the story of Inanna's Descent into the Underworld, he leads Inanna through the seven gates of the underworld,[44][45] removing one of her garments at each gate so that when she comes before Ereshkigal she is naked and symbolically powerless.[44][45] Belet-Seri is a chthonic underworld goddess who was thought to record the names of the deceased as they entered the underworld.[46] Enmesarra is a minor deity of the underworld.[47] Seven or eight other minor deities were said to be his offspring.[47] His symbol was the suššuru (a kind of pigeon).[47] In one incantation, Enmesarra and Ninmesharra, his female counterpart, are invoked as ancestors of Enki and as primeval deities.[47] Ennugi is "the canal inspector of the gods".[16] He is the son of Enlil or Enmesarra[16] and his wife is the goddess Nanibgal.[16] He is associated with the underworld[47] and he may be Gugalanna, the first husband of Ereshkigal, under a different name.[16]

Demons

The ancient Mesopotamians also believed that the underworld was home to many demons,[3] which are sometimes referred to as "offspring of arali".[3] These demons could sometimes leave the underworld and terrorize mortals on earth.[3] One class of demons that were believed to reside in the underworld were known as galla;[48] their primary purpose appears to have been to drag unfortunate mortals back to Kur.[48] They are frequently referenced in magical texts,[49] and some texts describe them as being seven in number.[49] Several extant poems describe the galla dragging the god Dumuzid into the underworld.[18] Like other demons, however, galla could also be benevolent[18] and, in a hymn from King Gudea of Lagash (c. 2144 – 2124 BC), a minor god named Ig-alima is described as "the great galla of Girsu".[18] Demons had no cult in Mesopotamian religious practice since demons "know no food, know no drink, eat no flour offering and drink no libation."[50]

Lamashtu was a demonic goddess with the "head of a lion, the teeth of a donkey, naked breasts, a hairy body, hands stained (with blood?), long fingers and fingernails, and the feet of Anzû."[51] She was believed to feed on the blood of human infants[51] and was widely blamed as the cause of miscarriages and cot deaths.[51] Although Lamashtu has traditionally been identified as a demoness,[52] the fact that she could cause evil on her own without the permission of other deities strongly indicates that she was seen as a goddess in her own right.[51] Mesopotamian peoples protected against her using amulets and talismans.[51] She was believed to ride in her boat on the river of the underworld[51] and she was associated with donkeys.[51] She was believed to be the daughter of An.[51]

Pazuzu is a demonic god who was well known to the Babylonians and Assyrians throughout the first millennium BC.[53] He is shown with "a rather canine face with abnormally bulging eyes, a scaly body, a snake-headed penis, the talons of a bird and usually wings."[53] He was believed to be the son of the god Hanbi.[54] He was usually regarded as evil,[53] but he could also sometimes be a beneficent entity who protected against winds bearing pestilence[53] and he was thought to be able to force Lamashtu back to the underworld.[55] Amulets bearing his image were positioned in dwellings to protect infants from Lamashtu[54] and pregnant women frequently wore amulets with his head on them as protection from her.[54]

Šul-pa-e's name means "youthful brilliance", but he was not envisioned as a youthful god.[56] According to one tradition, he was the consort of Ninhursag, a tradition which contradicts the usual portrayal of Enki as Ninhursag's consort.[56][57] In one Sumerian poem, offerings are made to Šhul-pa-e in the underworld and, in later mythology, he was one of the demons of the underworld.[56]

See also

- Ancient Mesopotamian religion – Western Asian body of religious beliefs

- Ghosts in Mesopotamian religions

- Land of Darkness – Mythical land

- Sumerian religion – First religion of Mesopotamia region which is tangible by writing

- World of Darkness – Underworld in Mandaeism

References

Notes

- In his book Sumerian Mythology, first published in 1944 and revised in 1961, the scholar Samuel Noah Kramer argued that Kur could also refer to a personal entity, a monstrous dragon-like creature analogous to the Babylonian Tiamat,[5] but this interpretation was refuted as unsubstantiated by Thorkild Jacobsen in his essay "Sumerian Mythology: A Review Article"[6] and is not mentioned in more recent sources.

Citations

- Choksi 2014.

- Barret 2007, pp. 7–65.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 180.

- Kramer 1961, p. 76.

- Kramer 1961, pp. 76–83.

- Jacobsen 2008a, pp. 121–126.

- Kramer 1961, p. 110.

- Horowitz 1998, pp. 268–269.

- Dalley 2008, p. 169.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 25.

- Black & Green 1992, pp. 58, 180.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 58.

- Black & Green 1992, pp. 180–181.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 181.

- Black & Green 1992, pp. 88–89.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 77.

- Nemet-Nejat 1998, p. 184.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 86.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 134.

- Holland 2009, p. 115.

- Horowitz 1998, p. 352.

- Leick 1998, p. 91.

- Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, p. 55.

- Kramer 1961, p. 90.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 136.

- Kasak & Veede 2001, p. 28.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 137.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 138.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 139.

- Black & Green 1992, pp. 139–140.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 140.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 72.

- Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 74–84.

- Ackerman 2006, p. 116.

- Jacobsen 2008b, pp. 87–88.

- Jacobsen 2008b, pp. 83–84.

- Jacobsen 2008b, pp. 83–87.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 73.

- Jacobsen 2008b, pp. 74–84.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 88.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 123.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 124.

- Black & Green 1992, pp. 123–124.

- Kramer 1961, p. 87.

- Wolkstein & Kramer 1983, pp. 157–159.

- Jordan 2002, p. 48.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 76.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 85.

- Black & Green 1992, pp. 85–86.

- cf. line 295 in "Inanna's descent into the nether world"

- Black & Green 1992, p. 116.

- Black & Green 1992, pp. 115–116.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 147.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 148.

- Black & Green 1992, pp. 147–148.

- Black & Green 1992, p. 173.

- George 1999, p. 225.

Works cited

- Ackerman, Susan (2006) [1989], Day, Peggy Lynne (ed.), Gender and Difference in Ancient Israel, Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, ISBN 978-0-8006-2393-7

- Barret, C. E. (2007), "Was dust their food and clay their bread?: Grave goods, the Mesopotamian afterlife, and the liminal role of Inana/Ištar", Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 7 (1): 7–65, doi:10.1163/156921207781375123, ISSN 1569-2116

- Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992), Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary, Austin: University of Texas Press, ISBN 0714117056

- Choksi, M. (2014), "Ancient Mesopotamian Beliefs in the Afterlife", World History Encyclopedia

- Dalley, Stephanie (2008). Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191027215.

- George, Andrew (1999), "Glossary of Proper Nouns", The Epic of Gilgamesh: The Babylonian Epic Poem and Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian, London, New York City, Melbourne, Toronto, New Delhi, Auckland, and Rosebank, South Africa: Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-044919-8

- Holland, Glenn Stanfield (2009), Gods in the Desert: Religions of the Ancient Near East, Lanham, MD; Boulder, CO; New York; Toronto; and Plymouth, UK: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., ISBN 978-0-7425-9979-6

- Horowitz, Wayne (1998), Mesopotamian Cosmic Geography, Mesopotamian Civilizations, Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, ISBN 978-0-931464-99-7

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (2008a) [1970], "Sumerian Mythology: A Review Article", in Moran, William L. (ed.), Toward the Image of Tammuz and Other Essays on Mesopotamian History and Culture, Dove Studies in Bible, Language, and History, Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, pp. 104–131, ISBN 978-1-55635-952-1

- Jacobsen, Thorkild (2008b) [1970], "Toward the Image of Tammuz", in Moran, William L. (ed.), Toward the Image of Tammuz and Other Essays on Mesopotamian History and Culture, Dove Studies in Bible, Language, and History, Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, pp. 73–103, ISBN 978-1-55635-952-1

- Jordan, Michael (2002) [1993], Encyclopedia of Gods, London: Kyle Cathie Limited, ISBN 978-0-8160-5923-2

- Kasak, Enn; Veede, Raul (2001), Kõiva, Mare; Kuperjanov, Andres (eds.), "Understanding Planets in Ancient Mesopotamia" (PDF), Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore, Tartu, Estonia: Folk Belief and Media Group of ELM, 16: 7–33, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.570.6778, doi:10.7592/FEJF2001.16.planets, ISSN 1406-0957

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1961), Sumerian Mythology: A Study of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Third Millennium B.C.: Revised Edition, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 978-0-8122-1047-7

- Leick, Gwendolyn (1998) [1991], A Dictionary of Ancient Near Eastern Mythology, New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-19811-0

- Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea (1998), Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia, Daily Life, Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, ISBN 978-0-313-29497-6

- Wolkstein, Diane; Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983), Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer, New York: Harper&Row Publishers, ISBN 978-0-06-090854-6