Jumper (computing)

In electronics and particularly computing, a jumper is a short length of conductor used to close, open or bypass part of an electronic circuit. They are typically used to set up or configure printed circuit boards, such as the motherboards of computers. The process of setting a jumper is often called strapping.

A strapping option is a hardware configuration setting usually sensed only during power-up or bootstrapping of a device (or even a single chip).[1]

Design

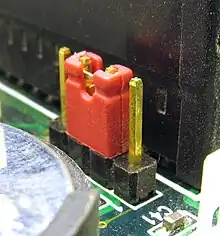

Jumper pins (points to be connected by the jumper) are arranged in groups called jumper blocks, each group having at least one pair of contact points. An appropriately sized conductive sleeve called a jumper, or more technically, a shunt jumper, is slipped over the pins to complete the circuit.

A two-pin jumper only allows to choose between two Boolean states, whereas a three-pin jumper allows to select between three states.

Jumpers must be electrically conducting; they are usually encased in a non-conductive block of plastic for convenience. This also avoids the risk that an unshielded jumper will accidentally short out something critical (particularly if it is dropped on a live circuit).

Jumper shunts can be categorized by their pitch (uniform distance between pins measured from center to center). Some common pitches are:

- 2.54 mm (0.100 in)

- 2.00 mm (0.079 in)

- 1.27 mm (0.050 in)

Use

When a jumper is placed over two or more jumper pins, an electrical connection is made between them, and the equipment is thus instructed to activate certain settings accordingly. For example, with older PC systems, CPU speed and voltage settings were often made by setting jumpers.

Some documentation may refer to setting the jumpers to on, off, closed, or open. When a jumper is on or covering at least two pins it is a closed jumper, when a jumper is off, is covering only one pin, or the pins have no jumper it is an open jumper.

Jumperless designs have the advantage that they are usually fast and easy to set up, often require little technical knowledge, and can be adjusted without having physical access to the circuit board. With PCs, the most common use of jumpers is in setting the operating mode for ATA drives (master, slave, or cable select), though this use declined with the rise of SATA drives and Plug and Play devices. Jumpers have been used since the beginning of printed circuit boards.[2][3]

Permanent parts of a circuit

Some printed wiring assemblies, particularly those using single-layer circuit boards, include short lengths of wire soldered between pairs of points. These wires are called wire bridges or jumpers, but unlike jumpers used for configuration settings, they are intended to permanently connect the points in question. They are used to solve layout issues of the printed wiring, providing connections that would otherwise require awkward (or in some cases, impossible) routing of the conductive traces. In some cases a resistor of 0 ohms is used instead of a wire, as these may be installed by the same robotic assembly machines that install real resistors and other components.

Jumpers setting configuration options not normally meant to be user-configurable can also be implemented as solder jumpers, typically two (or more) pads positioned closely together or even with interwoven shapes. Typically non-conductive by default they can be easily changed into a closed connection due to deliberately placed solder bridge on top of them. If the closed state is the default state, the PCB designer can superimpose a thin trace, which would be cut (with a knife) to open the jumper.

See also

References

- "USB251xB/xBi - USB 2.0 Hi-Speed Hub Controller" (PDF). Microchip Technology Inc./ Standard Microsystems Corporation (SMSC). 2015-07-15 [2010]. DS00001692C. Retrieved 2021-11-12. (57 pages)

- Weedmark, David (2013-06-13). "How to Use Jumpers on a SATA Hard Drive". Small Business - Chron.com. Retrieved 2023-06-01.

- "jumper settings". th99.80x86.ru. 2007-05-18. Archived from the original on 2007-10-23. Retrieved 2023-06-01.

External links

- Jumper Settings Archive at the Wayback Machine (archived 2007-10-11)