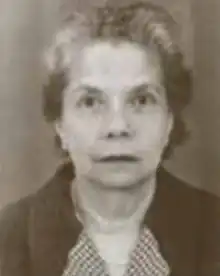

Julia Adolfs

Julia Adolfs (24 September 1899 – 16 November 1975) was the first woman of Indo-European descent to practice law in the Dutch East Indies. She studied at Leiden University in the Netherlands and began to practice in 1927 in Surabaya where she gained a reputation for practicing criminal law. Acting as an attorney for Chinese clients and Royal Dutch Shell (citation needed) she became prominent, investing her earnings in rental properties. When Indonesia gained independence, her properties were nationalized and she eventually moved to Monaco. A scholarship bearing her name is presented by the University of Amsterdam as a research grant for law students.

Julia Adolfs | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Julia Henriëtte Adolfs 24 January 1899 Semarang, Dutch East Indies, The Netherlands |

| Died | 16 November 1975 (aged 76) Amsterdam, The Netherlands |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Other names | Julia Jaarsma-Adolfs, Julia Henriëtte Jaarsma-Adolfs |

| Occupation | lawyer |

| Years active | 1927–1961 |

| Known for | first woman lawyer in the Dutch East Indies |

| Relatives | Gerard Pieter Adolfs (brother) |

Early life

Julia Henriëtte Adolfs was born on 24 January 1899 in Semarang, Dutch East Indies to Henriëtte (née Donkel) and Cornelis Gerardus Adolfs, as one of eight children.[1][2] Her older brother Gerard, known as "Ger" would become a renowned painter. Her father, a native of Amsterdam, was tall and blond. He had a degree in architecture and was known for his skill as an amateur painter, photographer and musician.[1] Her mother's family, of Javanese ancestry, owned a livestock breeding farm.[3] After completing her primary and secondary education in Java,[4] Adolfs wrote to distant relatives in the Netherlands hoping they could help her to continue her education. With their help, she enrolled in Leiden University,[3] and completed her doctoral examination to practice law in the Dutch East Indies in 1926.[4]

Career

Adolfs returned to Java, as the first woman lawyer of the colony. In March 1927, she joined the law firm in Surabaya operated by Sytze Jaarsma.[4] Five months later Adolfs and Jaarsma married[5] and they would subsequently have three daughters. Jaarsma preferred the study of law and his casework often centered on the fundamental rights of Europeans in the colony. Adolfs on the other hand preferred the practice of law.[3] Though she argued cases on family, inheritance, or real estate law,[6][7][8] her specialty was criminal law.[3] She defended some of the most notorious criminals in the port city and had many Chinese clients.[9] Newspapers reported that the two lawyers who made a name for themselves at the time litigating on behalf of Chinese businessmen were Adolfs and Victor Ploegman.[10] Because of the nature of her work and the numerous Chinese artifacts which adorned her home, it was often rumored that she participated in smuggling and took a percentage of the earnings of her clients' gains. A former judge who often worked with Adolfs wrote in 1972 that "She was certainly a major criminal lawyer and the best I met during my long career of almost half a century".[3]

By the early 1930s, Adolfs also served as a public prosecutor in the Supreme Court of Justice of Surabaya[7] and had an established record as a lawyer for Royal Dutch Shell. Using the profits from her work, she invested in rental properties, amassing 110 units prior to Indonesian Independence. During the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies during the Second World War, the family were imprisoned for three and a half years in various internment camps. After the Japanese withdrew, the family home was in the center of intense fighting during the Bersiap and Adolfs and Jaarsma sent their daughters to safety to attend school in the Netherlands. When the Indonesian National Revolution ended in independence for Indonesia, Adolfs' properties were nationalized. Long after other Dutch citizens had left Java,[3] and even after her husband's death in 1959,[11] Adolfs remained in Surabaya filing mostly unsuccessful claims to restore her property.[3]

Later life and legacy

In 1961, Adolfs finally left Indonesia and reunited with her daughters in the Netherlands. She died on 16 November 1975 in Amsterdam and was buried in the Westerveld Cemetery in Driehuis.[11] In 2015, when Adolfs' last surviving daughter, Trudie Vervoort-Jaarsma died, she bequeathed €4 million of the combined family capital to the University of Amsterdam in the name of her mother and her own daughter, Madeleine Vervoort. It was the largest single bequest left to a Dutch university by a private citizen.[9] The scholarship fund named after Adolfs is a research grant for the law faculty, while the fund named after Vervoort is a travel grant, in recognition that attaining an education often requires collecting data in various locations.[12]

References

Citations

- Borntraeger-Stoll & Orsini 2008, p. 17.

- Population Register 1899, p. 25.

- Goutbeek 2016, p. 13.

- De Indische Courant 1927, p. 5.

- Algemeen Handelsblad 1927, p. 6.

- Nieuwe Courant 1948, p. 4.

- De Indische Courant 1932, p. 3.

- De Indische Courant 1939, p. 4.

- Wiegman 2016.

- De Indische Courant 1940, p. 5.

- Begraafplaats Westerveld 2005.

- Goutbeek 2016, p. 14.

Bibliography

- Borntraeger-Stoll, Eveline; Orsini, Gianni (2008). Jansen, Frans (ed.). Gerard Pieter Adolfs: 1898–1968: The Painter of Java and Bali. Wijk en Aalburg, The Netherlands: Pictures Publishers. ISBN 978-90-73187-62-7.

- Goutbeek, Albert (July 2016). "Geschiedenis van Drie Generaties Vrouwen Leidt Tot Nalatenschap van Vier Miljoen" [History of Three Generations of Women Leads to Legacy of Four Million]. Spui. Vol. 44, no. 1. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Alumni Association of the University of Amsterdam. pp. 12–14. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Wiegman, Marcel (7 June 2016). "Wie was de vrouw die de UvA een Indisch kapitaal naliet?" [Who Was the Woman Who Left UvA East Indian Capital?]. Het Parool (in Dutch). Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Begraafplaats Westerveld Duin en Kruidbergerweg". online-begraafplaatsen.nl (in Dutch). The Netherlands. 2005. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Executoriale Verkoop" [Executorial Sale]. De Indische Courant (in Dutch). Vol. 272. Surabaya, Dutch East Indies. 10 August 1932. p. 3. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Familieberichten: Getrouwd" [Family messages: Married]. Algemeen Handelsblad (in Dutch). Vol. 32494. Amsterdam, the Netherlands. 16 August 1927. p. 6. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "Population Register: Julia Henriëtte Adolfs". openarch.nl. Leiden, The Netherlands: Erfgoed Leiden en Omstreken. 24 January 1899. p. 25. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "Pro-Deo: Executoriale Verkoop" [Pro-Deo: Executorial Sale]. De Indische Courant (in Dutch). Vol. 157. Surabaya, Dutch East Indies. 20 March 1939. p. 4. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Soerabaia's Advocate" [Surabaya's Lawyer]. De Indische Courant (in Dutch). Vol. 162. Surabaya, Dutch East Indies. 28 March 1927. p. 5. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "Van Het Landgerecht: In de wachtkamer" [From the Country Court: In the waiting room]. De Indische Courant (in Dutch). Vol. 140. Surabaya, Dutch East Indies. 28 February 1940. p. 4. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "(untitled, text begins: Bij expiloit van den deurwaarder)" [Exploitation of the bailiff]. Nieuwe Courant (in Dutch). Vol. 3, no. 41. Surabaya, Dutch East Indies. 21 February 1948. p. 4. column 1. Retrieved 2 September 2019.