Judeo-Moroccan Arabic

Judeo-Moroccan Arabic is the variety or the varieties of the Moroccan vernacular Arabic spoken by Jews living or formerly living in Morocco.[2][3] Historically, the majority of Moroccan Jews spoke Moroccan vernacular Arabic, or Darija, as their first language, even in Amazigh areas, which was facilitated by their literacy in Hebrew script.[4]: 59 The Darija spoken by Moroccan Jews, which they referred to as al-‘arabiya diyalna ("our Arabic") as opposed to ‘arabiya diyal l-məslimīn (Arabic of the Muslims), typically had distinct features,[4]: 59 such as š>s and ž>z "lisping," some lexical borrowings from Hebrew, and in some regions Hispanic features from the migration of Sephardi Jews following the Alhambra Decree.[3] The Jewish dialects of Darija spoken in different parts of Morocco had more in common with the local Moroccan Arabic dialects than they did with each other.[5]: 64

| Judeo-Moroccan Arabic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native to | Israel, Morocco, France |

| Ethnicity | Moroccan Jews |

Native speakers | 66,000 (2000–2018)[1] |

| Hebrew alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | aju |

| Glottolog | jude1265 |

| ELP | Judeo-Moroccan Arabic |

Nowadays, speakers of the language are usually older adults.[6] The young generation of the Jews of Morocco who studied at schools of the Alliance Israelite Universelle under the French protectorate made French their mother tongue.

The vast majority of Moroccan Jews have relocated to Israel and have switched to using Hebrew as their native language. Those who immigrated to metropolitan France typically use French as their first language, while the few still left in Morocco tend to use either French, Moroccan or Judeo-Moroccan Arabic in their everyday lives.

History and composition

Historically

Widely used in the Jewish community during its long history there, the Moroccan dialect of Judeo-Arabic has many influences from languages other than Arabic, including Spanish (due to the close proximity of Spain), Haketia or Moroccan Judeo-Spanish, due to the influx of Sephardic refugees from Spain after the 1492 expulsion, and French (due to the period in which Morocco was colonized by France), and, of course, the inclusion of many Hebrew loanwords and phrases (a feature of all Jewish languages). The dialect has considerable mutual intelligibility with Judeo-Tunisian Arabic, and some with Judeo-Tripolitanian Arabic (which, like Judeo-Moroccan Arabic, are associated with Maghrebi Arabic), but almost none with Judeo-Iraqi Arabic.

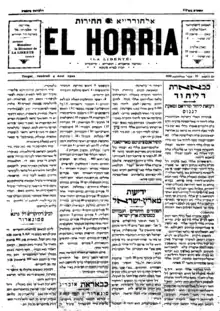

Most literate Muslims in Morocco would write, not in vernacular Arabic, but in Standard Arabic, but Moroccan Jews, who typically did not learn Standard Arabic as it was taught in Islamic religious contexts, wrote in Darija using Hebrew script.[4]: 59 For them, Darija was a literary language: Judah ibn Quraish wrote a risala on Semitic languages in Maghrebi Judeo-Arabic to the Jews of Fes already in the ninth-century.[4]: 59

Today

The vast majority of Morocco's 265,000 Jews emigrated to Israel after 1948, with significant emigration to Europe (mainly France) and North America as well. Although about 3,000 Jews remain in Morocco today,[7] most of them speak French rather than Judeo-Moroccan,[8] and their Arabic is more akin to Moroccan Arabic than to Judeo-Arabic. There are estimated to be 8,925 speakers in Morocco, mostly in Casablanca and Fes, and 250,000 in Israel (where speakers reported bilingualism with Hebrew). Most speakers, in both countries, are elderly. There is a Judeo-Arabic radio program on Israeli radio. It also has an impact on the language of Moroccan Jews on the economic and geographic peripheries of Israel, in places such as Beersheba as portrayed in Zaguri Imperia.[9]

Varieties

Simon Levy identifies three groups of Judeo-Moroccan Arabic based on the pronunciation of the letter qaf (in traditional Maghrebi Arabic script: ق, in Hebrew script: ק): 1) the dialects of Jewish communities in Fez, Sefrou, Meknes, Rabat, and Salé, which pronounce the qāf as a hamza or glottal stop; 2) the dialects of Marrakesh, Essaouira, Safi, el-Jadida, and Azemmour, which pronounce it as a voiced post-velar occlusive [q]; and 3) the dialects of Debdou, Tafilalt, and the Draa River valley, which pronounce it as a voiced velar occlusive [k].[3]

References

- Judeo-Moroccan Arabic at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- Sibony, Jonas (September 2019). "Curses and profanity in Moroccan Jewish-Arabic and what's left of it in the Hebrew sociolect of Israelis from Moroccan origins". Romano-Arabica. XIX.

- Levy, Simon (2013). "Les parlers arabes des juifs du Maroc". Langage et société. 143 (1): 41. doi:10.3917/ls.143.0041. ISSN 0181-4095.

- Gottreich, Emily (2020). Jewish Morocco. I.B. Tauris. doi:10.5040/9781838603601. ISBN 978-1-78076-849-6. S2CID 213996367.

- Bensimon-Choukroun, Georgette. Langues en contact dans le judéo-arabe de Fès : le système consonantique. OCLC 1201718554.

- Raymond G. Gordon Jr., ed. 2005. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. 15th edition. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- "EJP | News | France | Jewish pilgrims flock to Morocco to honour celebrated rabbis". Archived from the original on 2012-05-18. Retrieved 2012-05-17.

- "Jewish Language Research Website: Judeo-Arabic". Archived from the original on 21 July 2020.

- Sibony, Jonas (2021-05-06). "Moroccan Arabic and Jewish‑Arabic in Hebrew as Spoken by Israelis of Moroccan Origin: The Case of the TV Show Zaguri Imperya". Yod (23): 131–148. doi:10.4000/yod.4553. ISSN 0338-9316. S2CID 236561204.

- Heath, Jeffrey, Jewish and Muslim dialects of Moroccan Arabic (Routledge Curzon Arabic linguistics series): London, New York, 2002.

- Stories in Judeo-Arabic by David Bensoussan

External links

- Reka Kol Israel radio station broadcasting a daily program in Judeo-Moroccan (Mugrabian)