Joseph Favre

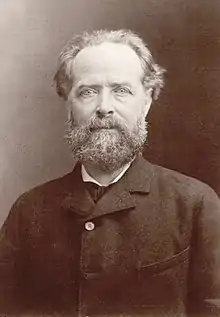

Joseph Favre (pronounced [ʒosɛf favʁ]; 17 February 1849 – 17 February 1903) was a famously skilled Swiss chef who worked in Switzerland, France, Germany, and England. Although he initially only received primary education because of his humble origins, as an adult he audited science and nutrition classes at the University of Geneva, and would eventually publish his four-volume Dictionnaire universel de cuisine pratique, an encyclopedia of culinary science, in 1895.

Joseph Favre | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 17 February 1849 |

| Died | 17 February 1903 (aged 54) |

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Occupation | Chef |

| Known for | Dictionnaire universel de cuisine |

As a young man, he enlisted in Giuseppe Garibaldi's army during the Franco-Prussian War and became an anarchist and a member of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA), also known as the First International. He founded and wrote for various left-wing journals and a magazine for chefs, and also sponsored cooking competitions and exhibitions and launched a chefs' trade union. He would come to favour a more moderate socialism and, like other members of the IWA in Switzerland, eventually rejected anarchism, though he remained active in radical politics. The Bishop of Orléans described his cooking as "diabolically good".

Early years

Joseph Favre was born on 17 February 1849 in Vex, in the canton of Valais in Switzerland. He was the illegitimate child of Victor Leblanc, a Catholic priest, and Madeleine Quinodox. He was orphaned as a young child and only received primary education.[1] Although he wanted to train as a doctor, the local lawyer who raised him told him that, because of his humble origins, he had to choose between becoming a priest or learning a manual trade.[2] When he was aged 14, he was sent as an apprentice cook to an aristocratic family in Sion, the capital of Valais. After his three-year apprenticeship, he moved to Geneva to work in the Hôtel Métropole, and at the same time took science classes at the University of Geneva.[2]

Favre was ambitious to become a master chef. In 1866, he went to Paris to broaden his experience.[2] He worked at La Milanese, a famous restaurant on the boulevard des Italiens, and then for the Maison Chevet, a well-known Parisian traiteur and caterer,[2] which had been founded by Hilaire-Germain Chevet shortly after the French Revolution. It supplied food and chefs for major functions in Paris and throughout Europe. According to Favre, "Chevet was not simply the supplier [of food] to French high society, but also to the high priests of European finance. An array of cooks, respected, respectful, and well-disciplined, would execute magnificent work."[3]

In the summer of 1867, he went to Chevet's Kursaal restaurant in Wiesbaden, reputedly one of the best in Europe. He worked during the next two years at the Taverne Anglaise in Paris, at the Royal Hotel, and the Hamburg Restaurant in London, and, after returning to Paris, at the Hôtel de Bade, the Café de la Paix, and then the Café Riche under the direction of Louis Bignon (1816–1906).[4]

Political activist

The Franco-Prussian War began in July 1870. Joseph Favre enlisted in Giuseppe Garibaldi's army of the Vosges. After peace came in 1871, Favre began a routine where he worked in hotels in the season, then spent the winters in Geneva, where he audited courses at the university. From 1873 to 1879, he worked in a number of fine restaurants and hotels in different parts of Switzerland.[4] He mixed in anarchist and socialist circles and became a friend of Élisée Reclus, Arthur Arnould, Jules Guesde, and Gustave Courbet.[1] Courbet painted Favre's portrait.[5]

Favre joined the International Workingmen's Association (IWA – often called the First International).[5] In 1874, while working in Clarens, he was a member of the IWA section of Vevey along with Reclus, Samuel Rossier, and Charles Perron.[6] In 1875, he was chef at the Hôtel du Parc in Lugano, in the Italian-speaking canton of Ticino. Giuseppe Nabruzzi, brother of the anarchist Lodovico Nabruzzi, also worked there.[1] In 1875, Favre, Lodovico Nabruzzi, and Tito Zanardelli founded the magazine L'Agitatore. Five issues appeared between 20 August and 20 October 1875.[6] In November 1875, Favre, Nabruzzi, Zanardelli, and Benoît Malon founded the Lake Lugano section of the International. They rejected insurrection in favor of evolutionary solutions, and supported trade unions.[7] Articles by Favre, Malon, Zanardelli, Natale Imperatori, and others appeared in the Almanacco del proletario pel 1876 ("1876 Workers' Almanac") in which they opposed anarchist insurrection.[6]

In the winter of 1875–76, Favre prepared a dinner for Mikhail Bakunin, Errico Malatesta, Reclus, Malon, and others, described in his dictionary of cooking, in which he created a recipe for a "Salvator" pudding. The room filled with the smoke of Turkish tobacco and Favre had to open the windows in cold weather. The group was ill-assorted, with different political views, wine and beer drinkers and abstainers, vegetarians and gourmets, but all could agree that the pudding was exquisite.[6] In March 1876, the Lake Lugano section finally broke with the anarchists.[6] In February 1877, Favre played an active role in the second congress of the Northern Italian section of the International Workingmen's Association (Federazione Alta Italia dell'Associazione Internazionale dei Lavoratori, or "FAIAIL"), where he spoke several times in favor of participating in parliamentary elections.[1] At the end of 1877, Favre was working in Bex. Malon, César De Paepe, Ippolito Perderzolli, and Favre co-founded the journal Le Socialisme progressif. Twenty-three issues appeared between 7 January and 30 November 1878.[6]

Master chef

Favre, like other great chefs of this period, was a follower of Antonin Carême and accepted his culinary theories concerning haute cuisine.[8] From 1873 to 1879, Favre worked in hotels and restaurants in Lausanne, Clarens, Fribourg, Lugano, Basel, Bex, and Rigi Kulm. In 1880, he was hired to reorganize the kitchens of the Central Hotel in Berlin. He spent eight months in Kassel with Count Botho zu Eulenburg, governor of Hesse, before finally returning to Paris.[4]

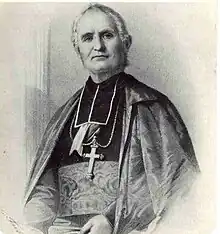

A story relates that in 1876, Favre was chef at the Hôtel Zaehringen in Fribourg, and prepared a light meal for the Bishop of Orléans, Félix Dupanloup, and the Empress Eugénie, who was travelling incognito.[9] It included a vol-au-vent with béchamel sauce and an unusual dish of duck stuffed with foie gras. After the meal, the bishop told the maître d'hôtel that he could not have eaten better on Olympus, and no doubt the cook was capable and religious. The maître d'hôtel said he was certainly capable, and he worked religiously. The bishop laughed and said he suspected as much, for the vol-au-vent was "diabolically good".[4]

On September 15, 1877, Favre launched La Science culinaire in Geneva, the first time a professional chef had run a journal.[4] The journal published contributions from chefs, and may have started the concept of applying science to cooking, although it would be many more years before theories of molecular gastronomy began to appear.[10] Favre was also the first to suggest the idea of culinary exhibitions and competitions, which would showcase the professional and artistic skills of chefs and cooks. They would have a teaching function, and would serve as qualifications to the chefs who passed the public tests. In 1878, the first culinary exhibition was held in Frankfurt.[11]

In 1879, Favre founded the Union Universelle pour le Progrès de l'Art Culinaire, which grew to 80 sections around the world.[1] The Société des Cuisiniers Français based in Paris was the main division of the union, and served as its headquarters. It published the journal L'Art Culinaire.[12] In April 1883, Favre and five others were expelled from the union "for their hostile actions in trying to bring about a split in the society." Favre founded a rival Academie culinaire. He continued to use the name of the Paris chapter of the Union Universelle despite legal action.[13] Favre's colleagues are said to have been upset that he sponsored cooking classes for the public and free lectures, since they thought he was revealing professional secrets.[14]

Last years

Favre retired to Boulogne-sur-Seine and spent the last years of his life preparing his great dictionary of cooking, whose first articles had appeared in La Science culinaire. The complete work in four volumes appeared in 1895, with this Notice to the Reader:[4]

Struck by the considerable number of fanciful terms and names given to dishes on restaurant menus and the menus of dining rooms, I have long thought that classification in the form of a dictionary, including the etymology, history, food chemistry, and properties of natural foods and recipes would be a book most useful to society.

At an 1889 congress, Favre recommended that young girls be given instruction in preparing foods for infants, adults, those in their declining years, and the old. By keeping food fresh and clean and following hygienic methods, they could use the immense resources of nature without danger.[15] He said, "there is an abyss between the greed of the Romans, who had to vomit before they could enjoy fresh gorging; the gluttonous gastronomy whose effects are indigestion, disorders and gout; and culinary science, which aims to achieve health through food that sustains virility, the fruitful development of the vital forces and sustains the intellectual faculties in their integrity. This gap must be filled. It is to France that the honor has been given of putting hygienic cooking into practice."[16][lower-alpha 1]

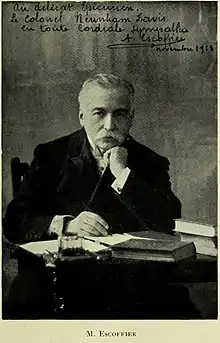

Joseph Favre died on 17 February 1903 in Boulogne-sur-Seine. He had almost completed a revision of his dictionary. A second edition appeared soon after his death in 1903, completed by his wife.[4] Along with Carême (1784–1833) and Auguste Escoffier (1846–1935), who admired him, Favre is one of the most famous names in French gastronomy.[17]

Works

- Favre, Joseph (1895). Dictionnaire universel de cuisine et d'hygiène alimentaire.

- Favre, Joseph (1903). Dictionnaire universel de cuisine pratique: encyclopédie illustrée d'hygiène alimentaire. L'Auteur. (Full text, as images, at the Gallica digital library of the Bibliothèque nationale de France)

See also

References

Footnotes

- French: Il y a un abîme entre la gourmandise des Romains, nécessitant le vomitif pour jouir d'une nouvelle déglutition; la gastronomie gloutonne dont les conséquences sont l'indigestion, les troubles et la goutte, et la science culinaire qui a pour but la véritable recherche de la santé par la cuisine qui entretient la virilité, le fécond développement des forces vitales et maintient les facultés intellectuelles dans leur intégrité. Cette lacune doit être comblée pour nous: c'est à la France qu'est dévolu l'honneur de mettre en pratique la cuisine hygénique.[16]

- Joseph Favre:ABMO.

- Trubek 2000, p. 69.

- Trubek 2000, p. 39.

- Epistémon 1936.

- Beck 1984, p. 203.

- FAVRE Joseph: Anarchici IN Svizzera.

- Brunello 2012.

- Mennell 1996, p. 149.

- Parienté & Ternant 1981, p. 316.

- Aguilera 2012, p. 311.

- Jacobs & Scholliers 2003, p. 219.

- Trubek 2000, p. 94.

- Mennell 1996, p. 171.

- This 2013, p. 71.

- Favre 1890, p. 1003.

- Favre 1890, p. 1002.

- La cuisine à quatre mains 2009.

Bibliography

- Aguilera, José Miguel (2012). Edible Structures: The Basic Science of what We Eat. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-9890-1. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- "FAVRE Joseph". Cantiere biografico degli Anarchici IN Svizzera (in Italian). Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- Beck, Leonard N. (1984). Two Loaf-Givers: Or a Tour Through the Gastronomic Libraries of Katherine Golden Bitting and Elizabeth Robins Pennell. Library of Congress. ISBN 978-0-8444-0404-2. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- Brunello, Piero (2012). "NABRUZZI, Lodovico". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). Vol. 77. Treccani. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- Epistémon (July 1936). "Joseph Favre 1849–1903". Grangousier, Revue de Gastronomie médicale (in French). Retrieved 2013-09-04.

- Favre, M.J. (1890). "De la cuisine hygiénique et de la nécessité des écoles de cuisine". Congrès d'Hygiène de 1889: Compte rendu (in French). Bibliothèque des Annales économiques. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- Jacobs, Marc; Scholliers, Peter (2003-06-01). Eating Out in Europe: Picnics, Gourmet Dining and Snacks Since the Late Eighteenth Century. Berg. ISBN 978-1-85973-658-6. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- "Joseph Favre". L'Internazionale italiana fra libertari ed evoluzionisti (in Italian). ABMO. Retrieved 2013-09-04.

- La cuisine à quatre mains (24 October 2009). "Immortel Escoffier". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- Mennell, Stephen (1996). All Manners of Food: Eating and Taste in England and France from the Middle Ages to the Present. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06490-6. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- Parienté, Henriette; Ternant, Geneviève de (1981). La fabuleuse histoire de la cuisine française (in French). Editions O.D.I.L. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- This, Hervé (2013-08-13). Building a Meal: From Molecular Gastronomy to Culinary Constructivism. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-51353-1. Retrieved 2013-09-05.

- Trubek, Amy B. (2000). Haute Cuisine: How the French Invented the Culinary Profession. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1776-6. Retrieved 2013-09-05.