Josef Rotter

Josef Rotter (fl. 1902–1914) was a teacher, illustrator, and editorial cartoonist of German or Austrian origin, most noted for his contribution to the Molla Nasreddin magazine.

Early life and education

Rotter's date and place of birth are not known. The best, yet far from precise, indication regarding his birthdate is a 1902 group photo at one of Rotter's workplaces, showing a man in his midthirthies to midfifthies[1] with an obvious resemblance to a caricature portrait of Rotter in the Jalil Mammadguluzadeh Encyclopedia.[2]

Rotter has been variously described as German,[3] German-born,[4] ethnic German,[5] and Austrian, without German necessarily referring to the German Empire, and with the term Austrian applied to Rotter in a meticulous, largely ethnographic work by Karl August Fischer.[6]

Rotter is said to have studied at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts,[7] but his name does not appear in the institution's exhaustively digitized 1809–1935 student matriculation books.[8]

1902–1914 Career

In 1902 Rotter accepted an invitation to teach at the newly founded Tbilisi Secondary School of Painting and Sculpture, the immediate precursor of the Georgian Academy of Fine Arts.[9] The invitation was issued by Oskar Schmerling, a second generation Caucasian German artist and director of the school, with whom Rotter would remain in close contact for years—the two men not only teaching at the same institution, but also traveling together, and contributing to many of the same magazines.[10]

From 1906 to 1914 Rotter engaged in a remarkably intense and multicultural activity, creating about twenty two hundred illustrations for seven periodicals, all based in Tbilisi but aiming at four linguistic groups over and beyond South Caucasia: the Armenian Khatabala, the Azeri Molla Nasreddin, the Georgian Eshmakis matrakhi, Nakaduli, Nishaduri, Tsnobis purtseli, and the German Kaukasische Post. [11] Five of these publications were launched in the wake of the 1905 Russian Revolution,[12] all took advantage of the subsequent relaxation of censorship,[13] and four were satirical magazines with pioneering content.[14]

Over eleven hundred of Rotter’s illustrations were published in Molla Nasreddin. Each issue of this weekly magazine, whose publication experienced multiple interruptions, had a close to eight-page editorial content, including four pages devoted to social or political cartoons. About a third of these fully illustrated pages in 1906–1907, half in 1908–1909, three-quarters in 1910–1913, nine-tenths in 1914, and three-fifths over the entire 1906–1914 period, were filled with Rotter’s work.[15] So Rotter’s role is seen as essential. Cartoons were meant to widen the audience of the magazine, include the less educated, and cross linguistic barriers; and indeed, Molla Nasreddin enjoyed a large circulation, with numerous schools and coffeehouses among its subscribers, and a geographic reach suggesting a far from exclusively Azeri readership.[16] So again Rotter’s role is seen as pivotal, but this time from a more qualitative point of view and in tandem with Schmerling, the publication’s other prominent illustrator. Finally, considering the impact of Molla Nasreddin as whole, or an aggregate of words and images, the magazine stands out as a successful proponent of progressive ideas in connection with the Muslim world, a model or reference point for the Armenian, Azeri, Georgian, Iranian, and Tatar press, and a significant force in the Persian Constitutional Revolution.[17]

In the same period, besides his editorial work, Rotter created nine illustrations for Abbas Ghayebzadeh's Azeri translation of Ferdowsi's Rostam and Sohrab, published in Tbilisi in 1908.[18]

Later life and death

Rotter’s collaboration with Tbilisi based periodicals came to a sudden end in the summer of 1914, shortly before the onset of Word War I.[19] Less than conclusive indications that Rotter survived the war are the first publications of some of his work in the 1920s and 1930s, viz. two sets of seven illustrations for Leopold Georg Ricek's narratives of Dietrich von Berne’s exploits published in Vienna in 1923 and 1924, and an album of twelve engravings dealing with Armenian myths and legends published in Yerevan in 1939.[20] The date and place of Rotter’s death are not known.

Gallery

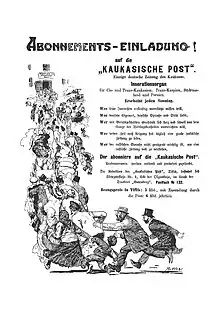

From the Kaukasische Post, January 17, 1910, no. 3, p. 18.

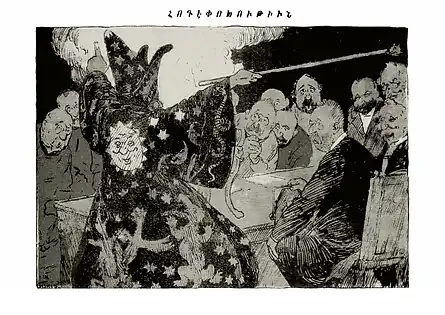

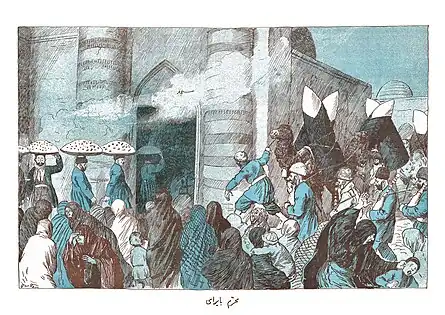

From the Kaukasische Post, January 17, 1910, no. 3, p. 18. From Khatabala, June 2, 1912, no. 21, p. 249.

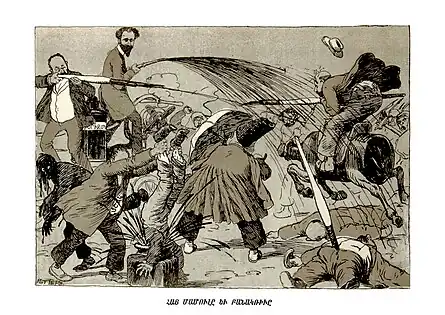

From Khatabala, June 2, 1912, no. 21, p. 249. From Khatabala, December 3, 1911, no. 49, p. 488.

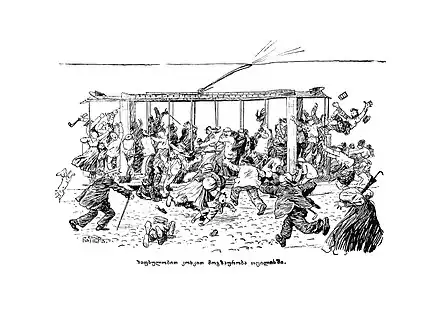

From Khatabala, December 3, 1911, no. 49, p. 488. From Matrakhi da salamuri, June 21, 1909, no. 2, p. 16.

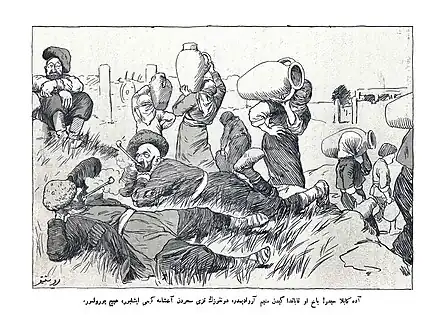

From Matrakhi da salamuri, June 21, 1909, no. 2, p. 16. From Molla Nasreddin, November 13, 1910, no. 36, p. 8.

From Molla Nasreddin, November 13, 1910, no. 36, p. 8. From Molla Nasreddin, January 12, 1911, no. 2, pp. 4-5.

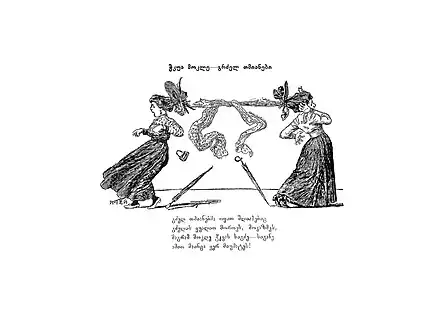

From Molla Nasreddin, January 12, 1911, no. 2, pp. 4-5. From Nakaduli: Saqmatsvilo zhurnali mtsiretslovantatvis, January 1912, no. 1, p. 4.

From Nakaduli: Saqmatsvilo zhurnali mtsiretslovantatvis, January 1912, no. 1, p. 4. From Nishaduri, 1907, no. 8, p. 4.

From Nishaduri, 1907, no. 8, p. 4. From Tsnobis purtseli: Suratebiani damateba, January 14, 1906, no. 372, p. 4.

From Tsnobis purtseli: Suratebiani damateba, January 14, 1906, no. 372, p. 4.

Notes

- Thirtieth photo in GAHPC (n.d.), third row, fourth person from the right. See also the undated photo in Caffee et al. (2023), second row, second person from the left. Both pictures were taken at the Arshakuni House, hosting the Caucasian Society for the Promotion of Fine Arts and the Tbilisi Secondary School of Painting and Sculpture (TSAA 2017, Eliozova 2018), whose connection with Rotter is described in the next section.

- UAW (2012). The portrait was first or beforehand published in the illustrated supplement to Tsnobis Furtseli, p. 4 of the April 6, 1903, no. 107 issue, where it is signed by Oskar Schmerling, and appears in a group of eight, not individually identified, but collectively described as “visual artists.”

- Guliyev and Rza (1984, 187), Javadi (2009), UAW (2012).

- Grant (2020, 8).

- Slavs and Tatars (2011, 6).

- Fischer (1944, 20–21, 80).

- Guliyev and Rza (1984, 187), UAW (2012).

- ABKM (2015).

- TSAA (2017), SovLab (n.d.).

- Caffee et al. (2023), Slavs and Tatars (2011, 7), Sovlab (n.d.).

- Based on Karimli, Nabiyev, and Mirahmadov (1996–2010), and online resources provided by the National Library of Armenia and Parliamentary Library of Georgia, the counts of Rotter’s illustrations in Eshmakis Matrakhi, Kaukasische Post, Khatabala, Nakaduli, Nishaduri, Molla Nasreddin, and the illustrated supplements to Tsnobis Furtseli are 18, 3, 840, 151, 16, 1161, and 22. The count for Eshmakis Matrakhi includes Rotter’s contributions to the magazine’s avatars Matrakhi, Matrakhi da salamuri, Salamuri, Chevni salamuri, Eshmaki, and Eshmakis salamuri (mentioned in WF (2022)). Similarly, the count for Nakaduli conflates the illustrations published in either its children’s or teenager’s editions.

- Abashidze (1984, 452), Fischer (1944, 14), Svanidze (2018).

- Daly (2009), Rigberg (1966).

- Bennigsen (1962, 505, 512), Svanidze (2018).

- Karimli, Nabiyev, and Mirahmadov (1996–2010).

- Bennigsen (1962, 507, 514), Grant (2020, 5, 8–9), Slavs and Tatar (2011, 5). While reported circulation numbers range from 2,500 to 25,000, and are commonly described as impressive, comparisons are made difficult by the uncertainty surrounding the proportion of Azeris, or more generally Turkophones, in Persia.

- Bennigsen (1962, 505, 508–512, 514).

- Ferdowsi (1908).

- Karimli, Nabiyev, and Mirahmadov (1996–2010), and online resources provided by the National Library of Armenia and Parliamentary Library of Georgia. The last issue of Molla Nasreddin with Rotter's illustrations is dated July 23, 1914 (Julian calendar).

- Ricek (1923, 1924), Armanavag (2014).

References

- Abashidze, Irakli, ed. 1984. Georgian Soviet Encyclopedia. Vol. 7. Tbilisi: Georgian Academy of Sciences.

- ABKM (Akademie der Bildenden Künste München). 2015. “Digitale Edition der Matrikelbücher 1809–1935.” Matrikelbücher.

- Armanavag. 2014. “Armenian Myths and Legends.” LiveJournal, March 26, 2014.

- Caffee, Naomi, et al. n.d. Beyond Caricature: The Oskar Schmerling Digital Archive.

- Bennigsen, Alexandre. 1962. “Mollah Nasreddin et la presse satirique musulmane de Russie avant 1917.” Cahiers du monde russe et soviétique 3 (3): 505–20.

- Daly, Jonathan D. 2009. “Government, Press, and Subversion in Russia, 1906–1917.” The Journal of The Historical Society 9 (1): 23–65.

- Eliozova, Irina. 2018. “The Caucasus Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts.” Propaganda.

- Ferdowsi, Abolqasem. 1908. Rostam o Sohrab. Translated by Abbas Ghayebzadeh. Tiflis: Gheyrat.

- Fischer, Karl August. 1944. Die „Kaukasische Post“. Leipzig: S. Hirzel Verlag.

- GAHPC (Georgian Association for the History of Photography in the Caucasus). n.d. “Gigo Gabashvili Collection.” The Georgian Museum of Photography. Accessed July 25, 2025.

- Grant, Bruce. 2020. “Satire and Political Imagination in the Caucasus: The Sense and Sensibilities of Molla Nasreddin.” Acta Slavica Iaponica 40: 1–18.

- Guliyev, Jamil, and Rasul Rza, eds. 1984. Azerbaijani Soviet Encyclopedia, Vol. 8. Baku: Azerbaijani Academy of Sciences, 1976–87.

- Javadi, Hassan. 2009. “Molla Nasreddin ii: Political and Social Weekly.” Encyclopaedia Iranica. .

- Karimli, Teymour, Bakir Nabiyev, and Aziz Mirahmadov, eds. 1996–2010. Molla Nasreddin. 7 vols. Baku: Azarbaijan Dowlati Nashriati, Chinar Chap.

- Ricek, Leopold Georg. 1923. Dietrich von Berne und seine Heergesellen. Vienna: Verlag von A. Pichlers Witwe und Sohne.

- Ricek, Leopold Georg. 1924. Dietrich von Berne und die Rabenschlacht. Vienna: Verlag von A. Pichlers Witwe und Sohne.

- Rigberg, Benjamin. 1966. “The Efficacy of Tsarist Censorship Operations, 1894–1917.” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas 14 (3): 327–346.

- SovLab (Soviet Past Research Laboratory). n.d. “Biographies.” Georgian-German Archive. Accessed July 25, 2023.

- Slavs and Tatars, ed. 2011. Molla Nasreddin: The Magazine that Would've, Could've, Should've. Zurich: JRP Ringier.

- Svanidze, Tamara. 2018. “Le journal satirique Le Martinet du Diable, observateur caustique de la première Republique de Géorgie.” Hypotheses.

- TSAA (Tbilisi State Academy of Arts). 2017. “History of the Academy.” Tbilisi State Academy of Arts.

- UAW (Union of Azerbaijan Writers). 2012. “Rotter Joseph.” Jalil Mammadquluzadeh Encyclopedia.

- Wikimedia Foundation. 2022. “Eshmakis Matrakhi.” Georgian edition of Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Accessed December 15, 2022.