José Roca y Ponsa

José Roca y Ponsa (1852–1938), known also as "Magistral de Sevilla", was a Spanish Roman Catholic priest. In historiography he is known mostly for his role in the 1899 conflict between the archbishops of Toledo and Seville. Catapulted to nationwide notoriety, in the early 1900s he was a point of reference for heated debates on religion and politics; today he is considered a representative of intransigent religious fundamentalism. Roca served as lecturing canon by the cathedrals of Las Palmas (1876-1892) and Seville (1892-1917), animated some diocesan periodicals, and published numerous booklets. He was one of very few nationally recognizable personalities of the Spanish Church who openly and systematically supported the Carlist cause, though he remained sympathetic also towards the Integrist breed of Traditionalism.

José Roca y Ponsa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | José Roca y Ponsa 1852 Vic, Spain |

| Died | 1938 Las Palmas, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | religious |

| Known for | priest, theorist |

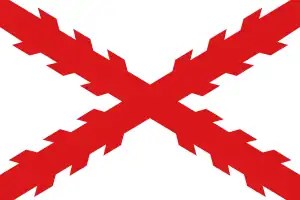

| Political party | Carlism |

Family and youth

.jpeg.webp)

The ancient Catalan family of Roca became very branched throughout the centuries, with its representatives scattered across all of the region. It is not clear what particular line the ancestors of Roca y Ponsa followed; none of the sources consulted provides any information on his distant forefathers. It is established that his father, Cayetano Roca Subirachs (1828-1918),[1] was a native of Vich; he formed part of the local bourgeoisie and in the mid-19th century either owned or otherwise operated a corset factory, manufacture or workshop.[2] At an unspecified time he married Engracia Ponsa; nothing is known either about her or about her family. The couple settled at Calle de la Riera. It is not clear how many children they had; among José's siblings there was at least one brother Cayetano[3] and two sisters, Dolores and Margarita.[4]

The children were brought up in a pious and religious home,[5] though there is no available information on José's childhood. A few sources claim that he “commenced ecclesiastic education” upon entering the local diocesan Vich seminary in 1861;[6] it is not clear whether at the age of 9 he was indeed admitted to the seminary or was rather attending a school run by local Church structures. Roca y Ponsa spent teenage years in his native town as a seminarian preparing for religious service. His education in Seminario de Vich was terminated in unclear circumstances, related to the fall of the Isabelline monarchy and the Glorious Revolution. Later, vague accounts suggest that in the early 1870s he was engaged either in the Carlist conspiracy or Carlist propaganda,[7] and that “in times of political agitation, persecutions, deportations” Roca y Ponsa was “declared undesirable and expelled from the peninsula in order not to interfere in consolidation of revolutionary work”.[8]

Either in late 1872 or in early 1873 Roca y Ponsa and 3 other Vich seminarians were transferred to the seminary in Las Palmas; it is there he completed bachillerato in teología in 1873.[9] He became a deacon in 1874 and was ordained a priest in 1875;[10] he held his first Mass on March 27, 1875.[11] Between June and September Roca y Ponsa served as ecónomo in the Canarian village of Artenara, where in 1876 he ascended to párroco castrense. The same year, and following a brief spell on the peninsula, he obtained bachillerato, licenciatura and doctorado of canon law in Granada.[12] Back on the Canary Islands he assumed teaching at the Las Palmas seminary, first as catedrático of Hermenéutica y Oratoria Sagrada[13] but over the years having classes also in Latin, philosophy, Hebrew and dogmatics.[14] Still in 1876 he passed exams for prebenda de Canónigo Lectoral by the Las Palmas cathedral.[15]

Ecclesiastic career

In Las Palmas Roca y Ponsa kept serving as lecturing canon by the cathedral and as catedrático by the local seminary. Another role he assumed was managing newly launched diocesan reviews.[16] He was gradually gaining recognition; in 1877 the Canary bishop José María Urquinaona nominated him head of the diocesan pilgrimage to Rome.[17] Roca was also assuming prestigious roles during local ceremonies.[18] His position in the Las Palmas hierarchy was enhanced with the 1879 arrival of the new bishop, José Proceso Pozuelo;[19] in 1881 Pozuelo nominated him to sort out the politically sensitive question of the local cemetery.[20] At the turn of the decades Roca launched a short-lived diocesan daily[21] and then a bi-weekly,[22] which he managed until 1888.[23] His militant articles aimed against the liberal regime cost him trial; in 1885 he was sentenced to living 3,5 years 25 km away from Las Palmas,[24] but it is not sure whether the sentence was enforced.[25] In 1890 Roca ascended to rectorship of Seminario de Canarias.[26]

In the early 1890s Roca was already basking in local prestige as a great preacher.[27] However, for reasons which remain unclear[28] he decided to leave the islands and applied for the position of canon at the Seville cathedral. In 1892 he was nominated canonigo penitenciario,[29] and in 1893 he took over Canongía Magistral.[30] His first years in Andalusia were uneventful, as in the mid-1890s he was noted merely for regular sermons.[31] Things changed in 1899 when Roca gained nationwide recognition following publication of his pamphlet directed against teachings of the primate, cardinal Sancha.[32] Because it was wrongly assumed that the criticism was authorised by the Seville archbishop Spínola[33] it caused a scandal and widespread debate.[34] As a well-known personality he was then active in Catholic congresses staged in the early 1900s. Though he gained recognition bordering notoriety, Roca did not progress in terms of his ecclesiastical career, especially since in 1911 his new booklets triggered a negative response from the Vatican.[35] Apart from his role of lecturing canon he assumed only some new teaching jobs in the local seminary,[36] at Hispalense,[37] and at various private establishments.[38]

In the mid-1910s Roca started to withdraw from active religious service, especially when in 1914 he suffered a grave accident[39] which led to continuous health problems.[40] Upon reaching the regular retirement age he resigned his canon position and in 1917[41] entered Congregación de Sacerdotes de San Felipe Neri, an order for retired chaplains.[42] On a decreasingly regular basis Roca kept delivering sermons at various Seville churches and in 1925 celebrated 50 years of priesthood.[43] A member of numerous religious congregations,[44] in the late 1920s he rose to executive roles in some[45] but his activity was limited by growing problems with eyesight.[46] His last sermons in Seville are dated for mid-1931; around that time he moved back to Las Palmas,[47] where he was taken care of by the family of his sister.[48] Half-blind,[49] he performed some minor local religious roles until the late 1930s.[50]

Catechist, publisher, author

Roca gained his name first as orator and already in 1879 he was assigned to deliver important sermons during prestigious religious events.[51] In the early 1890s he was locally well known in Las Palmas for his homilies,[52] the image then reinforced during the 25-year-service in Seville.[53] His sermons, passionate and militant, were “a skillful mixture of dogmatic theology and modern apologetics in the refutation of errors of our times”; a few of them were later gathered and published in separate booklets. Some later commentators appreciated Roca's popularization of great apologists but they note also that because of “the fire of his blunt and passionate word”, in his case “orator surpassed theoretician”.[54] Especially after 1910 Roca used to speak also at secular venues, usually marked by right-wing militancy; some were half-scientific sessions commemorating personalities like Jaime Balmes[55] and Marcelino Menendez Pelayo[56] or Traditionalism-flavored, openly political conferences.[57]

For about 15 years Roca was the moving spirit behind a number of Catholic Canarias periodicals, either issued directly by the bishopric or by related institutions. Since the early 1870s he managed a El Golgota,[58] though its lifetime is uncertain;[59] it went beyond the format of a local parochial print, as thanks to Roca's ingenuity El Golgota had correspondents in France, England and Italy.[60] In 1879 he launched a diocesan daily, El Faro Católico de Canarias.[61] It was probably rather short-lived, as in 1881 Roca focused on a new bi-weekly[62] La Revista de las Palmas. It turned out to be a more lasting enterprise, with youth supplement Los Jueves de la Revista added in 1885; as director, Roca[63] managed the publication until 1888.[64] Having moved to Seville in 1899 Roca launched a diocesan daily El Correo de Andalucia and for a while was its key editor.[65] In the 1900s he vigorously took part in conferences known as Asamblea Nacional de Buena Prensa[66] and until the early 1910s remained active in their Sevillan outpost, inspecting Catholic papers in terms of their orthodoxy.[67]

Between 1873 and 1935 Roca published some 15 booklets, formatted either as collections of essays, often based on his earlier sermons, or as pamphlets.[68] They usually dwelled on religion and politics; the author used to offer his – routinely highly critical – diagnosis of Spanish public life, and advanced his own suggestions for the future. Some were responses to specific issues, persons or episodes;[69] some contained more general lectures.[70] Roca used to sign with various, easily attributable pen-names,[71] though he was best known as "Magistral de Sevilla";[72] his late writings were published under his own name.[73] The booklet which made particular impact and caused nationwide controversy was Observaciones que el capitulo XIII del opúsculo del cardenal Sancha ha inspirado a un ciudadano español (1899).[74] ¿Se puede, en conciencia, pertenecer al partido liberal-conservador? (1912) and ¿Cuál es el mal mayor y cuál es el mal menor? (1912) also gained sort of notoriety, namely when the Vatican voiced its skepticism as to the political intransigence advanced; moderate Catholics were quick to stigmatize them as “doctrinas condenadas por Su Santidad”.[75]

Outlook

Roca y Ponsa gained his name mostly thanks to views on religion and politics. They were underpinned by confidence that a community without an officially accepted and enforced orthodoxy, a community where various concepts of public life constantly compete for domination, can not form an orderly, peaceful, operational society. In his view the only appropriate orthodoxy was Catholicism, which for centuries shaped the Spanish self and contributed to greatness of the nation; Catholic principles should serve as guidelines organizing both state and society. Their antithesis was liberalism, not only useless as a political doctrine, but also unacceptable as a moral concept; it remained responsible for decline of Spain and would lead to further calamities in the future.[76] Roca's view was fairly typical for some sections of the Spanish society, yet it was expressed in a most absolute and intransigent form; politics was viewed as battleground between God and Satan.

Roca understood Spanish public life as constant confrontation between Liberalism and Christianity, the two being clearly incompatible. He classified all political groupings into just two categories: liberal and anti-liberal ones;[77] basically, only the Carlists and the Integrists were considered part of the latter;[78] all other parties formed the ungodly, sinister liberal camp. Roca reserved particular criticism for the Conservatives,[79] who accepted the Restoration political framework;[80] though theoretically catering to Christian sections of the society, in fact with their hypocrisy they undermined Christian values.[81] They were guilty of accepting an erroneous understanding of lesser evil, which in fact paved the way for revolution;[82] similarly, he blamed for “malmenorismo” also some sections of the religious hierarchy. It was his pamphlet against the primate, who called for Catholics to “remain faithful and trust in the [liberal] government”, that caused heated nationwide debate, especially since Roca quoted papal authority.[83]

In the early 1900s Roca tried to format the emerging popular Catholic political movement, which at the time was taking shape at numerous Catholic congresses, as a vehicle of militant intransigent policy.[84] He tried to orient them towards rejection of malmenorismo, which in practical terms would have stood for adopting an anti-regime posture; having failed, he then denounced the congresses as doomed[85] and based on false principles.[86] Though at the time classical Spanish liberalism was in decline, giving way to new socialist and republican movements, Roca did not re-focus his approach; for him, new radical revolutionary ideas were merely extreme embodiments of liberalism. While absolutism – also considered a brainchild of the liberal fallacy - was usurpation of an individual, republicanism, nationalism or socialism were also usurpations against godly order, but attempted in the name of specific groups.[87] He kept opposing also social-Catholic and Christian-democratic movements, tailored to operate in a liberalism-ridden democratic regime and guilty of abandoning unity between religious and political objectives.[88]

Carlist

Roca was one of very few recognizable figures of the Catholic Church who openly and systematically supported the Carlist cause. He inherited Carlist enthusiasm from his father.[89] As Vich was “a city known as a centre of clerical Carlism and Integrism”[90] Roca got his zeal reinforced during the seminary years; involved in Carlist conspiracy in the early 1870s, he was then forced to move to the Canary Islands.[91] Under his management El Golgota, theoretically a Catholic diocesan periodical, became almost undistinguishable from local Las Palmas Traditionalist reviews of the late 1870s;[92] also Roca's sermons and writings were increasingly saturated with the Traditionalist vision of religion and politics. The same line was maintained in La Revista of the 1880s; the bi-weekly assaulted Carlist breakaways led by Pidal[93] and supported the intransigent anti-regime line advocated by Nocedal.[94] However, when in 1888 the latter broke away from orthodox Carlism himself to set up the branch known as Integrism, Roca did not take sides and remained equidistant.[95] Some sources refer to him as “ardent Integrist”,[96] some name him “blockhead Carlist”,[97] and some note that his departure to Andalusia weakened the position of both Canarian Carlists and Integrists.[98]

During his Canarian and Andalusian spells Roca did not engage in Traditionalist political structures, though following the move back to the peninsula his relations with the movement strengthened; under pen-names he contributed to the unofficial Carlist mouthpiece El Correo Español[99] and other regional party dailies,[100] helped to launch El Radical, a Seville periodical issued by the local Juventud Jaimista,[101] toured the country invited by Jaimista youth,[102] or attended party banquets hailing the Carlist leader Bartolomé Feliú;[103] in return, Roca was cheered as great theorist and author by various Carlist bodies.[104] However, he cultivated also the Integrist link; on some public conferences he appeared jointly with pundits like Manuel Senante,[105] remained on friendly terms with Juan Olazábal and perhaps contributed also to the chief Integrist daily, El Siglo Futuro.[106]

As a key attendant Roca took part in a grand Carlist meeting known as Magna Junta de Biarritz of 1919 and delivered one of his key lectures;[107] his embrace with the claimant Don Jaime was among iconic scenes from the rally.[108] In 1920 Roca helped to re-format[109] a Catholic daily El Correo de Andalucia and employed Domingo Tejera as its manager, paving his future path as a Traditionalist editor.[110] In 1924 Don Jaime conferred upon Roca the Orden de la Legitimidad Proscrita.[111] In 1930 and along other Carlists, Roca interacted with cardenal Segura, perplexed about his statements which appeared to endorse Alfonsism;[112] the same year he assisted in a grand rally of Andalusian Integrists.[113] In the first Republican elections of 1931 he ran in Las Palmas as independent Catholic candidate,[114] but failed disastrously.[115] In the early 1930s he was hailed as the great pundit of the cause[116] and indeed in 1934 the claimant Alfonso Carlos nominated him the second member of Consejo de Cultura Tradicionalista;[117] as such, in 1935 he published at least one piece in the Carlist intellectual review Tradición.[118]

Reception and legacy

Until the late 1890s Roca y Ponsa was known locally and appreciated in Catholic circles of Las Palmas and Sevilla for his unyielding, well-delivered sermons.[119] It was the 1899 Sancha–Spínola controversy which catapulted him to nationwide notoriety; Traditionalist dailies saluted him as righteous Christian,[120] while progressist papers ridiculed him as reactionary relic.[121] The issue was formally brought before the Vatican; the pronouncement of the Extraordinary Congregation for Ecclesiastic Affairs, which somewhat ambiguously sided with Sancha,[122] was welcomed with relief in governmental circles;[123] also the regent Maria Christina spoke out.[124] The debate demonstrated that Roca was not isolated among the Spanish clergy, and at one point it seemed that the episcopate was uncertain about the way forward.[125] However, in the following decades the Church opted for a moderate political strategy; Roca's defeat was sealed by another official Vatican pronouncement of 1911; it stated that though doctrinally correct, his writings were not official political recommendations for Catholics.[126] Since the 1910s Roca remained a champion of Catholic virtues only for extreme right-wing groupings like Integrists or Carlists.[127]

Save for a single article written during early Francoism,[128] after death Roca y Ponsa generally fell into oblivion. He has been only marginally present in the Carlist discourse. A 1961 collective work listed him among all-time masters of Traditionalism.[129] It seems that in the 1970s in Seville there was an organisation named Fundación Roca y Ponsa, yet there is nothing known about its activity.[130] In the 1990s the Canarian Carlists attempted to revive his memory; they set up Círculo Tradicionalista Roca y Ponsa in Las Palmas,[131] launched a project on Catholic counter-revolutionary thought on the islands[132] and operated a dedicated web page.[133] The initiative died out; there is only one minor biographic article on Roca[134] and another one on his early writings from the 1870s.[135] Currently he is mentioned – rather marginally – on some Traditionalism-flavored websites.[136] Occasional religious publications dedicated to Las Palmas or Seville note his contributions, though usually only in passing.[137]

.jpg.webp)

In present-day historiography Roca features almost exclusively as a protagonist of the Sancha–Spínola affair. He is typically presented as representative of reactionary, sectarian currents,[138] who advanced intolerant fanaticism and provoked a grave crisis between the archbishops of Toledo and Seville.[139] He might also be noted as author of primitive, run-of-the-mill, anti-Darwinian tirades,[140] failed contender in early discussions on Spanish political Catholicism,[141] or a sample of ultramontanism.[142] More favorably disposed scholars list him among theorists like Manterola, Mateos Gago and Sardá y Salvany[143] or position him as a classical example of Integrism.[144] In wide public discourse Roca is almost absent; if noted, he is mentioned as the one who triggered a conflict between two hierarchs.[145] In 2012 he was unexpectedly elevated to protagonist of an urban legend in-the-making. A podcast series Milenio 3, focused on paranormal activity, suggested that a house in Villanueva de Ariscal, Roca's home during his Seville tenure, was haunted; the authors floated gossip speculations about his private life.[146] There is a street commemorating Roca in Las Palmas.

Citations

- in some sources his segundo apellido is spelled as "Subirat", see e.g. La Gaceta de Tenerife 09.04.18, available here. However, the official death certificate of José Roca y Ponsa adheres to the "Subirachs" spelling, Partida de defunción de José Roca y Ponsa, [in:] Registro Civil de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 97-1 (95): 49

- Coses del Vic vell (13 setembre 1863), [in:] Diari de Vic 05.05.1933, available here

- Cayetano died in 1912, La Prensa 17.06.12, available here

- Dolores married Manuel González Martín, descendant to a bourgeoisie Las Palmas family. She died shortly afterwards and the widower married her sister, Margarita. The two commenced a prestigious Canarian branch of González Roca, José Miguel Alzola, Don José Roca y Ponsa, [in:] José Miguel Alzola, La Real Cofradia del Santísimo Cristo del Buen Fin y la Ermita del Espíritu Santo, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 1992, ISBN 8460421279, p. 38. The niece of Roca y Ponsa, Carmen González Roca, was founder of Las Catequistas del Pino, Julio Sánchez Rodríguez, Curas Catalanes en Canarias, [in:] La Provincia. Diario de Las Palmas 05.12.17, pp. 8-9, available here

- Roca Subirachs was noted in 1871 as donating money to jubileo pontificio of Pio X, El Pensamiento Español 07.06.71, available here

- B. de Artagan [Reinaldo Brea], Políticos del Carlismo, Barcelona 1903, p. 278, Juan María Roma (ed.), Album histórico del Carlismo, Barcelona 1933, p. 223

- “su adhesión al tradicionalismo catalán le crearon grandes dificultades con la Autoridad civil, viéndose obligado a abandonar aquella diócesis y a acogerse a la hospitalidad brindada por la de Canarias”, Alzola 1992, p. 38

- Tradición 01.02.33, available here

- José Miguel Barreto Romano, Manifestaciones de la división de los católicos durante el obispado de José Pozuelo y Herrero (1879-1890), [in:] Almogaren 22 (1998), p. 67

- Roma 1933, p. 223, José Fermín Garralda Arizcun, José Roca y Ponsa, [in:] Real Academia de Historia service, available here

- La Gaceta de Tenerife 07.04.25, available here

- Roma 1933, p. 223, Barreto Romano 1998, p. 67, Brea 1903; p. 278

- Sánchez Rodríguez 2017, p. 8

- Brea 1903, p. 278

- Sánchez Rodríguez 2017, p. 8

- Roma 1933, p. 223, Jaime del Burgo, Bibliografia del siglo XIX. Guerras carlistas. Luchas políticas, Pamplona 1978, p. 438

- Roma 1933, p. 223

- e.g. in 1878 Roca spoke during the Las Palmas ceremony marking the death of Pius IX, Jesús Perez Plasencia, El pontificado de Pio IX visto por un cura ultramontano desde Canarias, [in:] Almogaren 22 (1998), p. 77

- Proceso Pozuelo served in 1863-1865 as the canon in Vich; he knew Roca since his childhood and later turned into his promoter, Barreto Romano 1998, p. 67

- the Las Palmas bishop contested “usurpación del cementerio catolico” of 1868 by the then Junta Revolucionaria, Del Burgo 1978, p. 345

- Del Burgo 1978, p. 345

- Del Burgo 1978, p. 846

- Agustín Millares Cantero, Anticlericales, masones y librepensadores en Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (1868-1931), [in:] Almogaren 22 (1998), p. 113

- the 1885 sentence was a follow-up of an 1883 article, published by Roca in La Revista de Las Palmas and titled El despotismo liberal; in very militant tone it protested official measures aimed against religious orders, Barreto Romano 1998, p. 69. Oddly enough, also in 1885 Roca was nominated by the official administration a Fiscal de la Subdelegación Castrense de Canarias, Brea 1903, p. 270

- the Las Palmas bishop tended to side with Roca, Barreto Romano 1998, p. 69

- Roma 1933, p. 223, Brea 1903, p. 279

- Roca used to give 3 sermons per day; the last one was usually the most improvised one and was considered the best, Tradición 01.02.33, available here. His Las Palmas sermons have allegedly inspired Domingo Tejera de Quesada, then an 8-year-old boy later turned a Carlist propagandist, Tradición 01.02.35, available here

- it is not known whether Roca’s decision to leave Canarias was related to departure of bishop Urquinona, who in 1890 left the islands to assume the bishopry of Segovia

- Roma 1933, p. 223

- Roma 1933, pp. 223-224

- apart from the cathedral Roca preached also to various local institutions and organisations, e.g. in 1897 he was noted as speaking to Hermandad de Monserrate in Seville, ABC 26.03.94, available here

- in 1899 the archbishop of Toledo and the primate, cardenal Sancha, published an article which called the clergy and the Catholics to remain faithful and trust in the government of Sagasta. Roca responded with an anonymous booklet Observaciones que al capitulo XIII del opúsculo del cardenal Sancha ha inspirado a un ciudadano español, which claimed that the primate went off limits and that Catholics were free to follow their own political preferences, for details see e.g. Cristóbal Robles Muñoz, Maura, un político liberal, Madrid 1995, ISBN 9788400074852, pp. 92-100

- since Roca’s Observaciones was published with the official “licencia ecclesiástica”, issued by the Seville archbishopry, Sancha assumed that Roca voiced on behalf of the Seville archbishop Marcelo Spínola, who was probably either unaware or vaguely aware of the content of the booklet. Later Sancha and Spínola got to know each other better, and in 1904, during coronation of Vírgen de los Reyes, a great Seville feast engineered by Spínola, it was Sancha who performed the act. This conciliatory gesture might be interpreted as some sort of apology on part of Spínola, ABC 04.12.2004, available here

- during the conflict, lasting for few months between 1899 and 1900, Roca’s “name reverberated across all Spain”, ABC 04.05.43, available here

- Cristóbal Robles, Cristóbal Robles Muñoz, José María de Urquijo e Ybarra: opinión, religión y poder, Madrid 1997, ISBN 9788400076689, p. 288

- La Gaceta de Tenerife 07.04.25, available here

- José-Leonardo Ruiz Sánchez, Catolicismo y comunicación en la historia contemporánea, Sevilla 2005, ISBN 9788447208937, p. 135

- like Escuela de Comercio, Nicolás Salas, Sevilla, crónicas del siglo XX, Sevilla 1991, ISBN 9788474056761, p. 170

- in 1914 Roca stumbled and fell during the service; the accident left him briefly unconscious, Diario de Valencia 11.04.14, available here

- considered at the brink of death, Roca was administered last rites, El Correo Español 11.12.14, available here

- some sources claim he resigned in 1916, La Gaceta de Tenerife 07.04.25, available here

- La Prensa 17.01.17, available here

- La Gaceta de Tenerife 07.04.25, available here

- e.g. in 1929 Roca was active in Hermandad Macarena, ABC 28.03.92, available here

- e.g. in 1929 Roca served as director of La Congregación Mariana del Magisterio, ABC 16.11.29, available here; he rose also to prefect of the Neri congregation, La Prensa 19.01.38, available here; in 1931 he was director espiritual de Real Asociación de Maestros de la Primera Enseñanza San Casiano, ABC 20.01.31, available here

- in 1928 in Seville Roca underwent the eyesight surgery, La Gaceta de Tenerife 17.11.28, available here

- exact date of Roca’s move from Seville to Las Palmas is not clear; his last fairly regular sermons in Seville were dated June 1931, ABC 11.06.31, available here

- La Prensa 19.01.38, available here

- Tradición 01.02.35, available here

- until death Roca was vicesuperior of Oratorio de los Padres Filipenses in Santa Cruz, La Prensa 18.01.38, available here

- Millares Cantero 1998, p. 116

- Tradición 01.02.35, available here

- e.g. in 1906 Roca delivered sermon during funeral of the archbishop Spínola Maestre, Sánchez Rodríguez 2017, p. 9

- ABC 04.05.1943, available here

- El Restaurador 13.09.10, p. 1

- La Correspondencia de España 15.07.12, available here

- ABC 05.09.10, available here

- some authors claim that Roca managed also El Triunfo and La Tregua, Roma 1933, p. 223, Del Burgo 1978, p. 438; however, other scholars claim these were independent Carlist dailies, Perez Plasencia 1998, p. 78

- Roma 1933, p. 223, Del Burgo 1978, p. 438

- Perez Plasencia 1998, pp. 78-79

- Del Burgo 1978, p. 345

- Del Burgo 1978, p. 846

- Del Burgo 1978, p. 547

- Millares Cantero 1998, p. 113

- Jesus Donaire, ¡El Correo de Andalucía cumple 120 años!, [in:] El Correo de Andalucía 02.02.19, available here

- e.g. in 1906 in Seville or in 1908 in Zaragoza, José Fermín Garralda Arizcun, José Roca y Ponsa, [in:] Real Academia de Historia service, available here

- Roca was active in Centro General de Sevilla, a local Andalusian body of Asociación Nacional de la Buena Prensa; he served as one of the “consultores”, José-Leonardo Ruiz Sánchez, Periodismo católico en Sevilla, [in:] José-Leonardo Ruiz Sánchez (ed.), Catolicismo y comunicación en la historia contemporánea, Sevilla 2005, ISBN 8447208931, p. 147

- in 1890 Roca published El hijo pródigo, a 3-act drama; it was actually played on stage in Las Palmas, María del Mar López Cabrera, Sobre la critica teatral en la prensa Gran Canaria (1853-1900), [in:] Signa: revista de la Asociación Española de Semiótica 14 (2005), p. 269

- El Licenciado Lorenzo García ante la Fé y la Razón (1876) was an onslaught on Darwinist theories as presented by a Canarian liberal theorist, Rafael Lorenzo y García; El Congreso de Burgos y el Liberalismo (1899) was highly critical commentary to the Catholic congress concluded in Burgos; Observaciones que el capitulo XIII del opúsculo del cardenal Sancha ha inspirado a un ciudadano español (1899) was repudiation of political recommendations of the primate; En propia defensa. Carta abierta al Excmo. Sr. Cardenal Sancha (1899) was a continuation of Observaciones; Las normas dadas en Roma a los integristas (1910) was summary of the Integrist pilgrimage to Rome; El Rey soberano y la Nación en Cortes. Ideas de Balmes recogidas por el Magistral de Sevilla (1911) was a historiographic essay on Jaime Balmes; De Liberalismo. Sobre las conferencias del P. Coloma (1912) was critical account of social theories advanced by Luis Coloma

- Bosquejo de la civilización moderna (1873), A los buenos españoles: la regeneración liberal (1899), Como debe combatirse al liberalismo en España? (1909), ¿Cuál es el mal mayor y cuál es el mal menor? (1912), ¿Se puede, en conciencia, pertenecer al partido liberal-conservador? (1912), El Dinero (articles collected from press, 1912), Lecturas morales para fomentar el espiritú de reparación (1927), Vivamos alegres (1933), El hombre. Su origen, naturaleza, vida terrenal y su destino (1935), Cristo-Maestro (1936)

- like "Ciudadano Español" or "Católico Español"

- as “Magistral de Sevilla” Roca signed Carta abierta al Excmo. Sr. Cardenal Sancha, Las normas dadas en Roma a los integristas, Como debe combatirse al liberalismo en España? or ¿Cuál es el mal mayor y cuál es el mal menor?

- this is how Roca signed Vivamos alegres or El hombre. Su origen, naturaleza, vida terrenal y su destino

- full title Observaciones que al capitulo XIII del opúsculo del cardenal Sancha ha inspirado a un ciudadano español, Sevilla 1899

- Robles, Robles Muñoz 1997, p. 288

- Compare excerpts from Observaciones: “Los males que pesan sobre la Iglesia española proceden de nuestras Constituciones liberales. No ha habido, no hay verdadera lucha con el protestantismo: ni éste ha hecho descreído al pueblo, ni ha pagado a profesores panteístas o racionalistas que corrompieran a la juventud, ni ha empobrecido al clero, ni ha encanallado nuestros espectáculos. Todo esto es obra del liberalismo, que sólo se ha presentado en España triunfador y dominador por medio del Constitucionalismo". Also: "Podré confiadamente afirmar que el Trono actual es el mismo de Alfonso XII y de Isabel II, y representa lo mismo que representó el año 1833 y siguientes, Doña María Cristina, augusta abuela de D. Alfonso XII... ¿Y quién duda que el Poder moderador en España, desde 1833, se ha identificado con el liberalismo; pues el liberalismo lo estableció, defendió tenazmente y rodeó con amor; a condición de que el Trono fuera fiel a la causa liberal y a sus partidarios, nunca les hiciera traición ni les abandonara, aunque tuviera que pasar por el bárbaro degüello de los Religiosos, el inmenso robo sacrilego (que diría Menéndez Pelayo) de los bienes de la iglesia y el rompimiento consiguiente con el Vicario de Cristo? Estos son los hechos consignados en la historia, de que no es posible dudar”, referred after Del Burgo 1978, p. 865

- ABC 30.12.12, available here

- during a Carlist conference of 1910 in Valencia Roca named Traditionalism “fuerza antirrevolucionaria y patriótica, única que se preocupa en reestablecer el impe-rio de Cristo"; he went on to note that “vosotros, los carlistas, sois la fuerza antirrevolucionaría de Europa. Los católicos de Italia y de Francia no cumplen con su deber”, ABC 05.09.10, available here

- ¿Se puede, en conciencia, pertenecer al partido liberal-conservador? caused outrage as Roca claimed that being a Catholic was not compatible to being a member of the Conservative Party, Cristóbal Robles Muñoz, Jesuitas e Iglesia Vasca. Los católicos y el partido conservador (1911-1913), [in:] Príncipe de Viana 192 (1991), p. 200. Particular criticism was reserved for these deemed traitors, who left the righteous Traditionalist camp, especially Unión Católica of Alejandro Pidal, Barreto Romano 1998, p. 59

- El Restaurador 23.09.08, available here

- the Conservative embracement of malmenorismo was since 1812 "mal gravísimo, causa de todas las injusticias de que es víctima la Iglesia en España, y de la indiferencia religiosa del pueblo, y de la pérdida de la fe en tantas almas". Its hypocrysy “engaña a los católicos, los divide y los debilita, al paso que hace posible y fácil el triunfo de la revolución más anticlerical, en las esferas del gobierno, sin sacudidas ni graves excesos contra el orden material, consiguiendo que, sin oposición suya, se conviertan esos excesos en leyes, sin alarma de los católicos, sin indignación, sin adecuada resistencia”, Del Burgo 1978, p. 865

- Barreto Romano 1998, p. 59

- Roca pointed out that the Pope did not tell the Spaniards to follow any dynasty or any constitution, Vic V. Cárcel, León XIII frente a los integristas españoles. El incidente Sancha-Spinola, [in:] Miscellanea Historiae Pontificiae 50 (1983), pp. 477-504

- José Fermín Garralda Arizcun, Proyeccion sociopolítica de los congresos católicos en España (1), [in:] Verbo 333-334 (1995), pp. 369, 373

- Roca clashed Alfredo Brañas as to the role of the Catholic congresses and their position versus liberalism, José Fermín Garralda Arizcun, José Roca y Ponsa, [in:] Real Academia de Historia service, available here

- Garralda Arizcun 1995, p. 374, Ruiz Sánchez 2005, p. 137

- according to Roca, absolutism and revolution are two forms of “espiritú de orgullo y rebeldía”, which grew out of “regalismo cismático de José II de Austria y del Galicanismo”, Perez Plasencia 1998, pp. 82-83

- compare e.g. his criticism of Gonzalo Coloma, Robles, Robles Muñoz 1997, p. 288

- Roca Subirachs remained a Carlist until death; already an octogenarian, in the 1910s he formed part of the Carlist Comité Provincial of Las Palmas, El Correo Español 23.11.10, available here, and in 1911 served as honorary member of Juventud Tradicionalista of Las Palmas, El Correo Español 07.04.11, available here

- “una ciudad que habia destacado como centro activo del carlismo clerical y integrismo”, Barreto Romano 1998, p. 67

- “su adhesión al tradicionalismo catalán le crearon grandes dificultades con la Autoridad civil, viéndose obligado a abandonar aquella diócesis y a acogerse a la hospitalidad brindada por la de Canarias”, Alzola 1992, p. 38

- Perez Plasencia 1998, p. 78

- Barreto Romano 1998, p. 59

- José Miguel Barreto Romano, Manifestaciones de la división de los católicos durante el obispado de José Pozuelo y Herrero (1879-1890), [in:] Almogaren 22 (1998), p. 54

- it appears that Roca’s traditionalism was deprived of the dynastic ingredient and was closer to the Integrist rather than to the Carlist blueprint. At one point he noted that “el tradicionalismo se avendría con la república si ésta confesase á Dios, y atacaría la Monarquía si sus Gobiernos le persiguiesen”, ABC 05.09.10, available here

- William James Callahan, The Catholic Church in Spain, 1875-1998, Lansing 2009, ISBN 9780813209616, p. 72

- El País 08.09.99, available here. Some scholars count Roca among very few Carlists “for ever” active in the 1930s, Manuel Martorell Pérez, Nuevas aportaciones históricas sobre la evolución ideológica del carlismo, [in:] Gerónimo de Uztariz 16 (2000), p. 104

- Barreto Romano 1998, p. 55

- Roma 1933, p. 224

- e.g. with Diario de Valencia, see Diario de Valencia 18.03.11, available here. In 1899 Roca promised his contribution to José Domingo Corbató, a somewhat unorthodox Carlist at odds with the religious hierarchy, José Andres Gallego, La política religiosa en España 1889-1913, Madrid 1975, ISBN 8427612478, p. 167. In 1909-1910 Roca managed also a Traditionalist Sevilla daily La Unidad Catolica, Concha Langa Nuño, De cómo se improvisó el franquismo durante la Guerra Civil: la aportación del ABC de Sevilla, Sevilla 2007, ISBN 9788461153336, p. 49

- José Fermín Garralda Arizcun, José Roca y Ponsa, [in:] Real Academia de Historia service, available here. In the 1910s Roca served also as director espiritual of Juventud Jaimista of Seville, Brea 1903, p. 279

- e.g. he visited Gijón, invited by the local Jaimista youth organisation, El Correo Español 06.03.12, available here

- El Correo Español 14.09.10, available here

- in 1908 Roca was awarded “pluma de oro” by the Carlist youth organisation from Madrid, El Correo Español 24.12.08, available here

- El Restaurador 24.09.08, available here

- Robles Muñoz 1991, p. 204

- Melchor Ferrer, Breve historia del legitimismo español, Madrid 1958, p. 102

- Diario de Valencia 04.12.19, available here

- with permission and assistance of the archbishop of Seville, La Gaceta de Tenerife 07.04.25, available here

- ABC 11.06.94, available here

- Correo de Tortosa 14.03.24, also La Cruz 14.03.24, available here

- Santiago Martínez Sánchez, El Cardenal Pedro Segura y Sáenz [PhD thesis Universidad de Navarra], Pamplona 2002, p. 151

- El Siglo Futuro 20.10.30, available here

- prior to fielding his candidature Roca obtained official permission from respective ecclesiastic authorities, El Siglo Futuro 19.06.31, available here

- Roca gathered 735 votes while the leading candidate was supported by 24,000 voters. Details in María Luisa Tezanos Gandarillas, Roca Ponsa, católico jaimista: Canarias, [in:], María Luisa Tezanos Gandarillas, Los sacerdotes diputados ante la política religiosa de la Segunda República: 1931-1933 [PhD thesis Universidad de Alcalá], Alcalá de Henares 2017, pp. 159-162

- Roma 1933, p. 224

- Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español, vol. XXX/2, Sevilla 1979, p. 44

- Deberes políticos de los católicos, [in:] Tradición 1935; see also Antonio M. Moral Roncal, La cuestión religiosa en la Segunda República Española: Iglesia y carlismo, Madrid 2009, ISBN 9788497429054, p. 230. Roca kept contributing to other Carlist papers, also these at the vergy of the party orthodoxy like El Cruzado Español, compare El Cruzado Español 11.04.30, available here. In a homage article in Tradición by Domingo Tejera, the editor whom Roca invited in 1920 to lead a diocesan Seville periodical, honored him by calling that the Carlists “formemos la guardia sobre la borda, y saludemos al viejo soldado de Cristo, nuestro capitán”, Tradicion 01.02.35, available here

- Tradición 01.02.35, available here

- see e.g. El Siglo Futuro 18.10.30, available here

- “pobre zopenco de Roca y Ponsa, magistral de Sevilla y carlista de clase de testaferros”, El País 08.09.1899, available here

- “El nuncio y la Santa Sede manifestaron su apoyo al cardenal Sancha, condenaron las críticas que había recibido su pastoral y reprobaron la conducta de Spínola. Sin embargo todo ello se hizo en secreto y, para no alimentar la polémica, se prohibió la publicación del folleto de Roca y Ponsa pero no se condenó su contenido. El comportamiento ambigüo de la Santa Sede ratificó al magistral de Sevilla en su convicción de que sus Observaciones no contenían nada reprobable ‘tanto en lo que atañe a las ortodoxias, como en lo que se refiere a las formas’, por lo que consideraba injusto que se prohibiese su publicación”, Gandarillas 2017, p. 160

- Robles Muñoz 1995, pp. 98-100

- the regent Maria Christina voiced her disgust with Observaciones to Spinola, but he did not condemn Roca and left Madrid without paying customary respects to the regent, Robles Muñoz 1995, p. 100

- Robles Muñoz 1995, p. 97

- Robles, Robles Muñoz 1997, p. 288

- at the turn of the 1910s and 1920s Roca was cultivated mostly by El Siglo Futuro and El Correo Español; see also homage articles in Carlist publications, Brea 1903, pp. 278-281, and Roma 1933, pp. 223-224

- ABC 04.05.43, available here

- Jacek Bartyzel, Nic bez Boga, nic wbrew tradycji, Radzymin 2015, ISBN 9788360748732, p. 106

- ABC 12.11.72, available here, also ABC 09.11.74, available here

- Perez Plasencia 1998, p. 75

- the project was launched as José Roca y Ponsa y el pensamiento "Católico, contra-revolucionario" en Canarias, to be financed by Real Sociedad Económica de Amigos del País de Las Palmas and La Fundación Mapfre-Guanarteme

- for defunct website of the organisation see here

- Manuel Ferrer Muñoz, Apuntes biográficos sobre don José Roca y Ponsa, Magistral de la Catedral de Sevilla, [in:] Actas del II Congreso de Historia de Andalucía, Córdoba 1996, vol. III, pp. 139-144. ISBN 8479590416

- Perez Plasencia 1998

- see e.g. Roca y Ponsa, José, 1852-1937, [in:] Fundación Ignacio Larramendi service, available here, or reference at FB account of Círculo Tradicionalista de Granada, available here

- see e.g. Alzola 1992

- Vic V. Cárcel, León XIII frente a los integristas españoles. El incidente Sancha-Spinola, [in:] Miscellanea Historiae Pontificiae 50 (1983), pp. 477-504

- see e.g. Lorena R. Romero Domínguez, La buena prensa: prensa católica en Andalucía durante la Restauración, Sevilla 2009, ISBN 9788493754815, p. 128, also Robles Muñoz 1995, p. 97, Robles, Robles Muñoz 1997, p. 288, Tezanos Gandarillas 2017, pp. 159-162, Cárcel Ortí 1989, pp. 249-355, Barreto Romano 1998, p. 67, Perez Plasencia 1998, p. 77, Millares Cantero 1998, p. 113, Salas 1991, p. 170

- El Licenciado Lorenzo García ante la Fé y la Razón was dubbed “run-of-the-mill anti-Darwinian tirade”, Thomas F. Glick, The Comparative Reception of Darwinism, Chicago 1988, ISBN 9780226299778, p. 332

- Ruiz Sánchez 2005, p. 138

- Perez Plasencia 1998

- Ruiz Sánchez 2005, pp. 135-138

- “caracterizado personaje del integrismo local”, Ruiz Sánchez 2005, p. 135; Feliciano Montero, Spanish Catholicism at the Turn of the Century and the Crisis of 1898, [in:] Studia historica 15 (1997), p. 235

- ABC 04.12.04, available here. Other, somewhat more sympathetic portraits of Roca in Alzola 1992, Garralda Arizcun 1995, Ferrer Muñoz 1996, and Sánchez Rodríguez 2017

- the podcast author, Iker Jimenez, suggested that Roca y Ponsa maintained an intimate relationship with his longtime servant, a certain Dolores Sánchez. As reportedly she suddenly disappeared, the locals allegedly speculated that Roca either murdered her or immured her alive in the dungeons of the house, Fenómenos paranormales: la finca del magistral, [in:] Sevilla ciudad de embrujo service, available here. Most feedback gathered suggests the story is faked in almost every detail, see comments under La casa encantada de Villanueva del Ariscal, [in:] Voces del Misterio service, available here

Further reading

- José Miguel Alzola, Don José Roca y Ponsa, [in:] José Miguel Alzola, La Real Cofradia del Santísimo Cristo del Buen Fin y la Ermita del Espíritu Santo, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 1992, ISBN 8460421279, pp. 38–40

- Vicente Cárcel Ortí, San Pío X, los Jesuitas y los integristas españoles, [in:] Archivum Historiae Pontificiae 27 (1989), pp. 249–355

- Manuel Ferrer Muñoz, Apuntes biográficos sobre don José Roca y Ponsa, Magistral de la Catedral de Sevilla, [in:] Actas del II Congreso de Historia de Andalucía, vol. 3, Córdoba 1996, pp. 139–144

- José Fermín Garralda Arizcun, Proyección sociopolítica de los Congresos Católicos en España (1889-1908) (I), [in:] Verbo 333-334 (1995), pp. 343–374

- Jesús Perez Plasencia, El pontificado de Pio IX visto por un cura ultramontano desde Canarias, [in:] Almogaren 22 (1998), pp. 75–103

- Julio Sánchez Rodríguez, Curas Catalanes en Canarias, [in:] La Provincia. Diario de Las Palmas December 5, 2017, pp. 8–9

- María Luisa Tezanos Gandarillas, Roca Ponsa, católico jaimista: Canarias, [in:], María Luisa Tezanos Gandarillas, Los sacerdotes diputados ante la política religiosa de la Segunda República: 1931-1933 [PhD thesis Universidad de Alcalá], Alcalá de Henares 2017, pp. 159–162

External links

- Las tres coronas de Pío el Grande: oración fúnebre de Pío IX que en las solemnes exequias celebradas en la Santa Iglesia Catedral de las Palmas de Gran Canaria pronunció el día 28 de febrero de 1878 el Sr. Dr. D. José Roca y Ponsa, canónigo lectoral y profesor del Seminario conciliar

- La Sagrada Biblia y los humanos conocimientos: discurso leído en la solemne apertura del curso académico de 1896 á 97 en el Seminario Conciliar de Sevilla

- El Congreso de Burgos y el Liberalismo

- Oración fúnebre del... Sr. Cardenal Don Marcelino Spinola y Maestre, Arzobispo de Sevilla

- ¿Cómo debe combatirse al Liberalismo en España?

- Las normas dadas en Roma á los integristas, y su explicación

- El Rey soberano y la nación en Cortes. Ideas de Balmes

- ¿Cuál es el mal mayor y cuál el mal menor?

- ¿Se puede, en conciencia, pertenecer al partido liberal-conservador?

- Roca y Ponsa at the RAH service

- Calle Magistral Roca Ponsa in Las Palmas

- Por Dios y por España; contemporary Carlist propaganda on YouTube