John Struthers (anatomist)

Sir John Struthers MD FRCSE FRSE (21 February 1823 – 24 February 1899) was the first Regius Professor of Anatomy at the University of Aberdeen. He was a dynamic teacher and administrator, transforming the status of the institutions in which he worked. He was equally passionate about anatomy, enthusiastically seeking out and dissecting the largest and finest specimens, including whales, and troubling his colleagues with his single-minded quest for money and space for his collection. His collection was donated to Surgeon's Hall in Edinburgh.[1]

John Struthers | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 21 February 1823 Brucefield, Dunfermline |

| Died | 24 February 1899 (aged 76) Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Resting place | Warriston Cemetery |

| Education | University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation(s) | Anatomist, professor |

| Employer(s) | U. Edinburgh, U. Aberdeen |

| Spouse | Christina Margaret Alexander |

| Children | Three sons, four daughters |

| Parent(s) | Alexander, Mary (Reid) |

Among scientists, he is perhaps best known for his work on the ligament which bears his name. His work on the rare and vestigial ligament of Struthers came to the attention of Charles Darwin, who used it in his Descent of Man to help argue the case that man and other mammals shared a common ancestor ; or "community of descent," as Darwin expressed it.

Among the public, Struthers was famous for his dissection of the "Tay Whale", a humpback whale that appeared in the Firth of Tay, was hunted and then dragged ashore to be exhibited across Britain. Struthers took every opportunity he could to dissect it and recover its bones, and eventually wrote a monograph on it.

In the medical profession, he was known for transforming the teaching of anatomy, for the papers and books that he wrote, as well as for his efficient work in his medical school, for which he was successively awarded medicine's highest honours, including membership of the General Medical Council, fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, the presidency of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, and finally a knighthood.

Early life

John Struthers was the son of Alexander Struthers (1767–1853) and his wife Mary Reid (1793–1859).[2] They lived in Brucefield, a large stone-built 18th century house with spacious grounds, which was then just outside Dunfermline; John was born in the house.[3] Alexander was a wealthy mill owner and linen merchant. He bought Brucefield early in the 19th century, along with Brucefield Mill, a linen spinning mill built in 1792. Flax for linen was threshed at the nearby threshing mill, and bleached in the open air near the house. There were still linen bleachers living in Brucefield House in 1841, but they had gone by 1851, leaving the house as the seat of the Struthers family.[3] Mary's father, Deacon John Reid, was also a linen maker. Alexander and Mary were married in 1818; the marriage, though not warmly affectionate, lasted until Alexander's death despite the large age difference. Both Alexander and Mary are buried at Dunfermline Abbey.[4]: 76

Struthers was one of six children, three boys and three girls. The boys were privately tutored in the classics, mathematics and modern languages at home in Brucefield House. They went out boating in summer, skating in winter on the nearby dam; they rode ponies, went swimming in the nearby Firth of Forth, and went for long walks with wealthy friends.[4]: 76 Both his older brother James and his younger brother Alexander studied medicine. James Struthers became a doctor at Leith Hospital. Alexander Struthers died of cholera while serving as a doctor in the Crimean War. His sisters, Janet and Christina, provided a simple education at Brucefield for some poor friends, Daniel and James Thomson. Daniel (1833–1908) became a Dunfermline weaver as well as a historian and reformer.[4]: 71

Medical career

Struthers studied medicine at Edinburgh University, winning prizes as an undergraduate. He completed his doctorate (M.D.) in 1845, becoming a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh at the same time. In 1847, the college licensed him and his brother James to teach anatomy in the Edinburgh Extramural School of Medicine. The courses that they taught at the medical school in Argyle Square, Edinburgh were recognized by the examining bodies of England, Scotland and Ireland.[4]: 77

He worked his way up at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary from "dresser" (surgical assistant), to surgical clerk, to house physician, house surgeon and finally full surgeon. His passion was for anatomy; he told the story of how he had been so concentrated on an anatomy dissection one day in 1843 that he failed to look outside to observe the street procession known as the "Disruption" which launched the Free Church of Scotland. He became Lecturer of Anatomy at the University of Edinburgh.[4]: 77

From 1860 Struthers was joined by William Pirrie at the university, who worked alongside Struthers as Professor of Surgery.[5]

In 1863, Struthers became the first Regius Professor of Anatomy at the University of Aberdeen.[6][7][2] This was a "Crown Chair" (a professorship recognized by the government), a prestigious position. Struthers' application for the chair was supported by over 250 letters, many from public figures including well-known doctors such as Joseph Lister and James Paget, and politicians such as Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, who became Home Secretary, and James Moncreiff, who became the Scottish Lord Advocate.[note 1] The support of these men was actively solicited by Struthers' well-connected friends and relatives, including his cousin the Reverend John Struthers of Prestonpans, and his energetic wife Christina. With the success of their campaign, the family moved to Aberdeen.[4]: 77

Struthers held the professorship at Aberdeen for 26 years. In that time, he radically transformed anatomy teaching at the university, improved the Aberdeen medical school; set up the museum of anatomy; and helped to lead the reconstruction of the Aberdeen Infirmary. He vigorously collected specimens for his museum, "prepared or otherwise provided, mainly by the work of my own hands, and at my own expense". The specimens were arranged to enable students to compare the anatomy of different animals. He intended the comparative anatomy exhibits to demonstrate evolution through the presence of homologous structures. For example, in mammals, the arm and hand of a human, the wing of a bird, the foreleg of a horse, and the flipper of a whale are all homologous forelimbs. He continually made demands of the University of Aberdeen's Senate for additional room space and money for the museum, against the wishes of his colleagues in the faculty.[8] Struthers could go to great lengths to obtain specimens he particularly wanted, and on at least one occasion this led to court action. He had long admired a crocodile skeleton at Aberdeen's Medico-Chirurgical Society. In 1866 he borrowed it, ostensibly to clean and remount it, but despite the society's urgent requests to have it returned, it stayed in Struthers' museum at Marischal College for ten years. Struthers still hoped to obtain the specimen, and when in 1885 he was made president of the Medico-Chirurgical Society, he again tried to take the crocodile to his museum. The society then obtained an interdict (a court order) restraining him from removing the skeleton.[9][10]

Struthers published about 70 papers on anatomy. He set up a popular series of lectures for the public, held on Saturday evenings.[4]: 78 Many of the methods he used remain relevant today. He had a powerful effect on medical education in Britain, in 1890 establishing the format of three years of "pre-clinical" academic teaching and examination in the sciences underlying medicine, including especially anatomy. His system lasted until the reform of medical training in 1993 and 2003. His 21st century successors at the anatomy school in Aberdeen write that "He would undoubtedly be greatly dismayed at the drastic reduction in the teaching of basic medical sciences, and the subsequent perceived decline in the anatomical knowledge of medical students and practicing clinicians," and they quote one of Struthers' sayings to his students:[9][10]

Unless you are well informed in the foundation sciences and principles, you may practise your profession, but you will never understand disease and its treatment; your practice will be routine, the unintelligent application of the dogmas and directions of your textbook or teacher.[11]

Scientific work

Evolution and Struthers' ligament

Struthers was one of the first advocates of the theory of evolution, speaking publicly[13] and corresponding with Charles Darwin[14] about observations he made during his comparative anatomy studies.

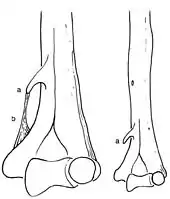

Struthers was interested in abnormal variations in anatomy, such as additional toes, and he collected many specimens which he offered to show Darwin. Among other curiosities, Struthers described the "Ligament of Struthers", a rare extra band of connective tissue present in 1% of humans running from a bony projection on the humerus down to the elbow,[15] and showed that its presence was inherited.[16][17][18][19]

The significance of Struthers' ligament, as Darwin and Struthers understood, is that the vestigial organ has no function in humans, but is inherited from a structure, the supra-condyloid foramen, which certainly had a function in other mammals including marsupials and carnivores. In those other mammals, the supra-condyloid foramen is an opening in the bone that important structures, the median nerve and the brachial artery, run through. Struthers observed that when his ligament was present in humans, the nerve and artery did run through it. Darwin took this to mean that the human structure was homologous with the foramen in other mammals, and that therefore humans and other mammals had a common ancestor. He used Struthers' work as evidence in Chapter 1 of his Descent of Man (1871):[15][20]

In some of the lower Quadrumana, in the Lemuridae and Carnivora, as well as in many marsupials, there is a passage near the lower end of the humerus, called the supra-condyloid foramen, through which the great nerve of the fore limb and often the great artery pass. Now in the humerus of man, there is generally a trace of this passage, which is sometimes fairly well developed, being formed by a depending hook-like process of bone, completed by a band of ligament. Dr. Struthers, who has closely attended to the subject, has now shewn that this peculiarity is sometimes inherited, as it has occurred in a father, and in no less than four out of his seven children. When present, the great nerve invariably passes through it; and this clearly indicates that it is the homologue and rudiment of the supra-condyloid foramen of the lower animals. Prof. Turner estimates, as he informs me, that it occurs in about one per cent of recent skeletons. But if the occasional development of this structure in man is, as seems probable, due to reversion, it is a return to a very ancient state of things, because in the higher Quadrumana it is absent.[20][note 2]

Whale anatomy

Aberdeen, a coastal city, gave Struthers the opportunity to observe the whales which were from time to time washed up on Scotland's coast. In 1870 he observed, dissected and described a blue whale (which he called a "Great Fin-Whale") from Peterhead. He brought the entire skeleton of a sei whale back to the anatomy department at Aberdeen, where for a century it was suspended overhead in the hall. He vigorously collected examples of a wide range of species to form a museum of zoology, with the intention of illustrating Darwin's theories. As an energetic and forceful personality with a strong enthusiasm for zoology, he alarmed his colleagues at the University of Aberdeen by constantly asking for money and space to acquire and house his collection.[8][21]

Dissecting the "Tay Whale"

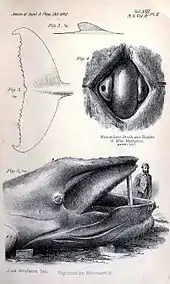

Struthers became known to the general public for his dissection of the "Tay Whale", one of his largest specimens.[8]

At the end of December 1883, a humpback whale appeared in the Firth of Tay off Dundee, attracting much local interest. It was harpooned, but after an all-night struggle escaped. A week later it was found dead, and was towed on to the beach at Stonehaven, near Aberdeen. Struthers quickly visited the carcass, measuring it as 40 feet long with a tail 11 feet 4 inches wide. Struthers was not able to start dissecting it at once, as a local entrepreneur, John Woods, bought the whale and took it to his yard in Dundee, where on the first Sunday, 12,000 people paid to see it.[8]

Struthers was not allowed to dissect the famous specimen until it was too badly decomposed for further public exhibition.[note 3] He was well used to working on stinking carcasses: his dissecting room was reputed to stink "like the deck of a Greenland whaler".[22] The dissection was disturbed by John Woods, who admitted the public, for a fee, to watch Struthers and his assistants at work, with a military band playing in the background. Progress on the dissection was impeded by snow showers. Struthers was able to remove much of the skeleton before Woods had the flesh embalmed; the carcass was then stuffed and sewn up to be taken on a profitable tour as far as Edinburgh and London. After months of waiting, on 7 August 1884, Struthers was able to remove the skull and the rest of the skeleton. Over the next decade, Struthers wrote seven anatomy articles on the whale, with a complete monograph on it in 1889.[8]

Life and family

Struthers' siblings included James Struthers MD (1821–1891), a doctor at Leith hospital for 42 years, and his youngest brother Alexander Struthers MB who died at Scutari Hospital in Istanbul during the Crimean War.[23]

Struthers married Christina Margaret Alexander (born 15 January 1833) on 5 August 1857. Christina was the sister of John Alexander, chief clerk to Bow Street Police Court. She too came from a Scottish medical family; her parents were Dr James Alexander (1795–1863) and Margaret Finlay (1797–1865), both of old Dunfermline families; James practised as a surgeon just across the English border in the small town of Wooler, Northumberland.[4]: 77 On James' death as a "country practitioner", the city-dweller Struthers wrote[24]

The great majority of the profession are and must be country practitioners; the hardest work of the profession is done by them; in the winter nights, when the world is asleep, they have many a long and weary drive; they are far from libraries, from hospitals and museums, and from societies; and thus in their comparative isolation want that stimulus and guidance which tend to keep the city practitioner up to the mark.[24]

Struthers was father-in-law of nitroglycerine chemist David Orme Masson, who married his daughter Mary. He was grandfather of another explosives chemist, Sir James Irvine Orme Masson, and father-in-law of educator Simon Somerville Laurie, who married his daughter Lucy.[25][26]

Retirement

On retiring from the University of Aberdeen, Struthers returned to Edinburgh. He lived at 15 George Square.[27]

He was buried in the north-east section of the central roundel of Warriston Cemetery, Edinburgh, in 1899; his wife Christina joined him there in 1907. The grave faces over a path to that of his brother, James Struthers.

All three of their sons, Alexander, James and John also worked in the medical profession; John William Struthers followed his uncle James by working at Leith Hospital, and followed his father by working at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary and by becoming president of the Royal College of Surgeons.[4]: 79

Awards and distinctions

In 1852 Struthers was elected a member of the Harveian Society of Edinburgh and served as president in 1894.[28] He was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree by the University of Glasgow in 1885 for his work in medical education.[4]: 78 [2] In 1892 he was given honorary membership of the Royal Medical Society; he also became president of the Royal Physical Society of Edinburgh.[4]: 78 He was appointed to the General Medical Council in 1883 and remained a member until 1891.[4]: 78 He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1894.[29] In 1895 he was made president of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh; he held the position for two years.[4]: 78 In 1898, he was knighted (as Sir John Struthers) by Queen Victoria for his service to medicine.[4]: 78 [30][31]

Glasgow University's Struthers Medal is named in his honour.[32]

Publications

Struthers authored over 70 manuscripts and books, including the following.

Books

- Struthers, John (1854). Anatomical and Physiological Observations. Edinburgh: Sutherland and Knox.

- Struthers, John (1867). Historical Sketch of the Edinburgh Anatomical School. Edinburgh: Maclachlan and Stewart.

- Struthers, John (1889). Memoir on the Anatomy of the Humpback Whale, Megaptera Longimana. Edinburgh: Maclachlan.

Papers

- Struthers, John (1854). "On some points in the abnormal anatomy of the arm". Br. Foreign Medico-Chir. Rev. 13: 523–533.

- Struthers, J (1863). "Contributions to Anatomy". The Lancet. Elsevier BV. 81 (2056): 87–88. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(00)63465-7. ISSN 0140-6736.

- Struthers, John (1871). "On some points in the anatomy of a Great Fin Whale (Balaenoptera musculus)". Journal of Anatomical Physiology. 6: 107–125.

- Struthers, John (1873). "On Hereditary Supra-Condyloid Process in Man". The Lancet. Elsevier BV. 101 (2581): 231–232. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)63384-7. ISSN 0140-6736.

- Struthers, John (1881). "On the bones, articulations and muscles of the rudimentary hind limbs of the Greenland Right Whale (Balena mysticetus)". Journal of Anatomical Physiology. 15: 141–321.

- Struthers, John (October 1893). "The New Five-Year Course of Study: Remarks on the position of Anatomy among the Earlier Studies, and on the relative value of Practical Work and of Lectures in Modern Medical Education". Edinburgh Medical Journal.

- Struthers, John (1895). "On the external characters and some parts of the anatomy of a Beluga (Delphinapterus leucas)". Journal of Anatomical Physiology. 30: 124–156.

Notes

- The text says 'Lord Grey'; but Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey had been prime minister until 1834. His younger brother Sir George Grey, 2nd Baronet later became Home Secretary, but in 1839–40 he held other ministerial roles. James Moncreiff became Lord Advocate in 1851.

- Darwin referenced this item in the Descent of Man as follows: "With respect to inheritance, see Dr. Struthers in the Lancet, Feb. 15, 1873, and another important paper, ibid., Jan. 24, 1863, p. 83. Dr. Knox, as I am informed, was the first anatomist who drew attention to this peculiar structure in man; see his Great Artists and Anatomists, p. 63. See also an important memoir on this process by Dr. Gruber, in the Bulletin de l'Acad. Imp. de St. Petersbourg, tom. xii., 1867, p. 448."

- Dissection began on 25 January 1884.

References

- "Key Object Page | Frog Skeleton". Surgeon's Hall Museums.

It is part of a collection of comparative anatomy put together by John Struthers (1823–1899), Scottish zoologist and anatomist. At one time, the museum held a whole array of animals, from a tiger skeleton and a dolphin skull, to the pulmonary vein of a whale and the skin of a porcupine fish. Much of what we do have will be featured in the new displays that open in September.

- Power, D'Arcy (1901). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). Vol. 3. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- (Historic Scotland). "Off Old Mill Court, Brucefield House, Dunfermline". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- "Living in the past | Sir John Struthers 1823–1899" (PDF). Dunfermline Heritage Community Projects. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Wallis, Patrick. "Pirrie, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/22313. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Gorman, Martyn, 2003. Introduction

- "Sir John Struthers Dead.; He Was Vice President of the Edinburgh College of Surgeons". The New York Times. 25 February 1899. Retrieved 21 June 2008.

- "Professor Struthers and the Tay Whale". Archived from the original on 11 November 2005. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- Waterston, S. W.; Laing, M. R.; Hutchison, J. D. (2007). "Nineteenth century medical education for tomorrow's doctors". Scottish Medical Journal. 52 (1): 45–49. doi:10.1258/rsmsmj.52.1.45. PMID 17373426. S2CID 30286930.

- Waterston, S. W.; Hutchison, J. D. (2004). "Sir John Struthers MD FRCS Edin LLD Glasg: Anatomist, zoologist and pioneer in medical education". The Surgeon. 2 (6): 347–351. doi:10.1016/s1479-666x(04)80035-0. PMID 15712576.

- Struthers, John (1856). "Hints to students on the prosecution of their studies: Being Extracts from the Introductory Address at Surgeons' Hall, Session 1855–56". Edinburgh Medical Journal. 2 (3): 353–60.

- Struthers J (1854). "On Some Points in the Abnormal Anatomy of the Arm". Br Foreign Med Chir Rev. 13 (26): 523–533. PMC 5185442. PMID 30164440.

- Struthers, John (24 February 1874). "Evolution". Aberdeen Daily Free Press. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- "Darwin Correspondence Project – Letter 4725 – Struthers, John to Darwin, C. R., 31 Dec 1864". Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- Gorman, Martyn. "The Zoology of Professor Struthers". Charles Darwin and Struthers' ligament. University of Aberdeen. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- Struthers, John (1863). "On the solid-hoofed pig; and on a case in which the fore foot of the horse presented two toes". Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal. 17: 273–80.

- Struthers, J. (1863). "Contributions to Anatomy". The Lancet. 81 (2056): 87–88. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)63465-7.

- Struthers, J. (1873). "On Hereditary Supra-Condyloid Process in Man". The Lancet. 101 (2581): 231–232. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)63384-7.

- Gorman, Martyn, 2003. Darwin & Struthers' Ligament.

- Darwin, Charles R. (1871). The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. John Murray. p. 28.

- Williams, M. J. (1996). "Professor Struthers and the Tay whale". Scottish Medical Journal. 41 (3): 92–94. doi:10.1177/003693309604100308. PMID 8807706.

- Pennington, C. The modernisation of medical teaching at Aberdeen in the nineteenth century. Aberdeen University Press, 1994.

- Leith Hospital 1848–1988, D H A Boyd, ISBN 0-7073-0584-5

- Struthers, John. Memoir of Dr Alexander, Wooler.

- Weickhardt, LW (2006). "Sir James Irvine Orme Masson (1887–1962)". Masson, Sir James Irvine Orme (1887–1962). ISSN 1833-7538.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Josipa Petrunic. "Simon Somerville Laurie". Gifford Lectures. University of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012.

- Edinburgh Post Office Directory 1899

- Watson Wemyss, Herbert Lindesay (1933). A Record of the Edinburgh Harveian Society. T&A Constable, Edinburgh.

- C.D. Waterson; A. Macmillan Shearer (July 2006). Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh: 1783 – 2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. ISBN 0-902198-84-X.

- "Sir John Struthers, M.D., LL.D". Nature. 59 (1533): 468–469. 1899. Bibcode:1899Natur..59..468.. doi:10.1038/059468a0.

- "Obituary: Emeritus Professor Sir John Struthers". Medical Press and Circular: 232. 1 March 1899.

- "Struthers Medal and Prize". University of Glasgow. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

Sources

- Darwin, Charles (1871). The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1st ed.). London: John Murray. ISBN 0-8014-2085-7. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- Gorman, Martyn (2003). "The Zoology of Professor Struthers". University of Aberdeen. Archived from the original on 26 April 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- "Struthers, Sir John (1823–1899), anatomist and medical reformer". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26680. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Waterston, S.W.; Hutchison, J.D. (December 2004). "Sir John Struthers MD FRCS Edin LLD Glas: anatomist, zoologist and pioneer in medical education" (PDF). The Surgeon. 2 (6): 347–351. doi:10.1016/S1479-666X(04)80035-0. PMID 15712576. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2014.

- Struthers, John (1863). Memoir of Dr Alexander, Wooler.

External links

- The Zoology of Professor Struthers Archived 26 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine at University of Aberdeen