John Mullan (road builder)

John Mullan Jr. (July 31, 1830 – December 28, 1909) was an American soldier, explorer, civil servant, and road builder. After graduating from the United States Military Academy in 1852, he joined the Northern Pacific Railroad Survey, led by Isaac Stevens. He extensively explored western Montana and portions of southeastern Idaho, discovered Mullan Pass, participated in the Coeur d'Alene War, and led the construction crew which built the Mullan Road in Montana, Idaho, and Washington state between the spring of 1859 and summer of 1860.

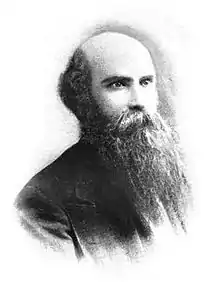

John Mullan Jr. | |

|---|---|

John Mullan in the 1870s or 1880s | |

| Born | July 31, 1830 Norfolk, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | December 28, 1909 (aged 79) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Soldier, civil servant, lawyer |

| Years active | 1852 to 1884 |

| Known for | Building the Mullan Road in Montana, Idaho, and Washington state |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1852–1863 |

| Rank | |

He unsuccessfully sought appointment as Territorial Governor of the new Idaho Territory, although he played a significant role in the territory's formation and the establishment of its boundaries. Leaving the United States Army in April 1863, he failed at several businesses before profiting immensely as a real estate dealer and land attorney in California. At one point, the law firm he co-founded was the largest land speculator in the state. He later became an agent and lobbyist for the states of California, Nevada, and Oregon and for the Washington Territory, securing reimbursements from the federal government. The tarnished reputation he earned as a land speculator, coupled with state politics, led the three states and the territory to deny him most of the income he expected to generate from this business. He died penniless and ill in 1909.

Mullan also served from 1883 to 1887 as one of the commissioners of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions, a private organization acting as an agent of the federal government.

Early life

Mullan was born in Norfolk, Virginia, on July 31, 1830,[1] to John and Mary (née Bright) Mullan. He was the oldest son of what would eventually be 11 children.[2] The Mullans moved to Annapolis, Maryland, in 1833. John Sr. had enlisted in the United States Army in 1823, and about the time of John Jr.'s birth was an ordnance sergeant.[3]

John Jr. began attending school in 1839.[2][4][lower-alpha 1] Despite the financial burden of raising so many children, the Mullans were able to finance secondary and higher education for John. He attended St. John's College in Annapolis, where he studied Greek, Latin, history, mathematics, philosophy, art, rhetoric, navigation, surveying, chemistry, and geology, among other subjects. Mullan graduated from St. John's in 1847[5] with a Bachelor of Arts degree.[6] He was just 16 years old.[2]

In 1845, Secretary of War William L. Marcy transferred the Army post of Fort Severn (which guarded the entrance to Annapolis harbor) to the United States Navy, which converted the fort into the United States Naval Academy. At Marcy's request, John Mullan Sr. was assigned to the Navy (he formally joined the Navy in 1855 at the age of 54), and spent the rest of his career doing light general repair and cleaning at the Naval Academy.[3]

West Point

Probably due to his father's lengthy career in the Army, John Mullan Jr. sought admission to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. The Mullan family were Democrats, and John Sr. had briefly served as an alderman on the Annapolis city council. This made the Mullans extremely well-connected politically, and several respected citizens of Annapolis (including St. John's president Hector Humphreys) wrote John Jr. glowing letters of recommendation. The entire Democratic delegation in the Maryland General Assembly petitioned President James K. Polk to admit him.[7]

In 1848, Mullan traveled to the White House in Washington, D.C., and asked Polk for an appointment to West Point.[lower-alpha 2] Sizing up the diminutive but muscular Mullan, Polk reportedly asked, "Well, don't you think you are rather small to want to be a soldier?" Mullan replied, "I may be somewhat small, sir, but can't a small man be a soldier as well as a tall one?" Polk, amused by Mullan's audacity, gave him the appointment[9] six weeks later.[10]

Mullan entered West Point on July 1, 1848.[10] About 70 percent of classroom time at West Point was spent on three subjects: engineering, mathematics, and science.[11] West Point was then the nation's preeminent engineering school, and Mullan studied under Dennis Hart Mahan, the nation's leading civil engineer.[12] Mullan's was one of the first classes of cadets to learn how to navigate using a compass and odometer.[13] Few cadets engaged in extracurricular reading at the West Point library, but Mullan checked out large quantities of books, many of them dealing with the newly acquired western United States.[13] He graduated in 1852, 15th in a class of 43.[14] Among Mullan's classmates were future generals such as George Crook, George B. McClellan, and Phil Sheridan.[12]

Mullan was commissioned a brevet 2d Lieutenant in the United States Army after graduating from West Point.[15] On July 1, he was assigned to Fort Columbus on Governors Island in New York Harbor.[16]

On November 4, 1852, Mullan left New York City aboard a steamship, traversed the Isthmus of Nicaragua, and arrived in San Francisco on December 1, 1852,[17] where he was assigned to the 1st Artillery Regiment.[18]

The Stevens survey

Preparations for the survey

On February 10, 1853, outgoing President Millard Fillmore signed legislation creating the Washington Territory.[19] On March 17, newly inaugurated President Franklin Pierce appointed one of his supporters, Isaac Stevens, to be Territorial Governor of Washington Territory. The Senate confirmed the appointment the same day.[20] Stevens knew that on March 3, 1853, Congress had appropriated $150,000 ($5,276,400 in 2022 dollars) to survey railroad routes across the Pacific Northwest. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis was eager to complete the surveys, which he believed would show a northern route to be impossible. This would force Congress to survey and fund the construction of a southern route, which in turn would lead to rapid development of the area and the creation of new slave-holding states (as permitted under the Missouri Compromise).[21] Davis was determined to move as swiftly as possible on the surveys, and on March 25, 1853, appointed Stevens to lead the survey project.[22]

The Stevens survey was the first transcontinental survey of the western United States since the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804–1806, and considered very important by the United States government.[23] Stevens largely had his pick of men for the survey project, and chose a wide range of common soldiers, laborers, topographers, engineers, doctors, naturalists, astronomers, geologists, and meteorologists.[23][lower-alpha 3] Private Gustav Sohon also served with the group.[25] Captain John W.T. Gardiner of the 1st Dragoons (cavalry) was appointed the chief officer of the group.[24] Mullan was assigned to the Stevens survey party as a topographical engineer.[lower-alpha 4] That Mullan, only recently arrived in San Francisco, would be ordered to join the Stevens survey is not unusual, as members of the team were drawn from all over the United States.[lower-alpha 5]

Mullan traveled east to the town of St. Louis,[33] a booming town in the state of Missouri. On May 10, while in St. Louis, Mullan was promoted to 2d Lieutenant[34] and assigned to the 2nd Artillery Regiment.[18][34][lower-alpha 6] Mullan now met with Stevens, Capt. Gardiner,[36] and Lieutenant Andrew J. Donelson Jr. of the Army Corps of Engineers.[33] Stevens, who arrived in St. Louis on May 15, 1853,[37] met Mullan[38] and instructed Donelson to take a party to Fort Union (at the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers near what is now the North Dakota/Montana border about 25 miles (40 km) from Williston, North Dakota) and establish a supply depot there.[lower-alpha 7]

Fort Union and Fort Benton

Donelson booked passage on the steamboat Robert Campbell for the trip. He and Mullan had interior cabins (which cost $100 each, or $3,518 in 2022 dollars), while the six sappers slept on the deck (at $47 each, or $1,653 in 2022 dollars).[41] The Donelson/Mullan party left St. Louis on May 21,[36] and arrived at Fort Union on July 3.[33] During the trip, Mullan made meteorological observations whenever the ship halted.[42][43] Mullan also assisted Donelson in mapping the territory the ship passed through from St. Joseph, Missouri to Fort Union.[42][43] During this trip, Mullan met his first Native Americans, members of the Eastern Dakota tribe.[43] The Robert Campbell deposited Donelson, Mullan, and their supplies at Fort Union.[44][45]

While at Fort Union, Donelson led Mullan and 11 other men on an exploration of the nearby country.[23] Departing the fort on July 12, they traveled 42 miles (68 km) up Big Muddy Creek, then proceeded due east to the White Earth River. They went down the White Earth River for 30 miles (48 km) before paralleling the Missouri River for another 62 miles (100 km) to reach Fort Union again.[44]

Stevens departed St. Louis for St. Paul, a small town in the Minnesota Territory, on May 23.[46] He and the majority of the survey party left St. Paul on May 28,[47] and extensively mapped the region along what is now Interstate 94. They finally reached Fort Union on August 1.[48] On August 9, the reunited survey party left Fort Union. Stevens originally intended for Donelson and Mullan to lead a party north along the Big Muddy to its headwaters (near modern Plentywood, Montana) before heading west along the border with Canada before turning south to reach Fort Benton[49]—the highest navigable point on the Missouri River.[50] He intended for the main body of the Stevens survey to travel slightly up the Missouri until it reached the Milk River. The main body would then follow the Milk River to a point near present-day Havre, Montana, before heading south to Fort Benton.[49] Traveling on the north bank of the Missouri, the united survey team crossed the Big Muddy on August 11.[51] Then Stevens changed his mind, and decided the entire party should travel together along the Milk, with only small mapping parties sent off at various points to briefly explore the surrounding land.[52] The group reached Fort Benton on September 1.[53] During the trip, Mullan made topographic and meteorological observations.[54]

Mission to the Salish

On September 9, Stevens sent Mullan on a peace mission to the Salish nation.[55] Mullan was instructed to convey the peaceful intentions of the government of the United States, implore the Salish to make peace with the Piegan Blackfeet, and express the desire of the United States to build up the settlement at St. Mary's Mission. Mullan was also to obtain several guides from the Salish, and to explore any nearby passes through the Rocky Mountains. Survey party aide F.H. Burr, three local men, a hunter, and a Piegan Blackfeet guide named White Crane accompanied him.[56][lower-alpha 8]

Mullan traveled south from Fort Benton along Shonkin Creek, west of the Highwood Mountains. Skirting the Little Belt Mountains by driving southeast, he crossed Arrow Creek, passed south through the Judith Gap (the Big Snowy Mountains to the east, the Little Belts to the west), and crossed several tributaries of the Judith River. Reaching the Musselshell River, he explored along its banks up and down stream for several miles, before striking south and finally finding the Salish encampment about 70 miles (110 km) south of the river.[60] On September 18,[55] Mullan encountered about 50 lodges of Salish and 100 lodges of Kalispel, who received him very warmly.[61] At one point during the meeting with the Salish, Stevens found himself without his interpreter. But after realizing a few Salish spoke French, Stevens was able to converse with them (having studied French for two years at West Point).[55] The Salish chief agreed to consider the goodwill message, and sent four of his men back with Mullan as guides to the mountain passes.[61]

Mullan and his companions then returned to the Musselshell, where his Piegan Blackfeet guide left him. The Mullan party followed the Musselshell's north branch to the west-northwest, then continued to the Smith River. They followed the Smith through the Castle Mountains until they reached the Missouri River. The Salish guides knew the area well, and led him across the Helena Valley to Prickly Pear Creek.[62] He crossed the Continental Divide on September 24 via "Hell Gate Pass",[62][lower-alpha 9] and descended the other side into the valley of the Little Blackfoot River. Essentially following what is today U.S. Route 12 and Interstate 90, he followed the river and its successor streams northwest to the Missoula Valley (entering near present-day Hell Gate, Montana), then proceeded south through the Bitterroot Valley to reach Fort Owen (near present-day Stevensville, Montana).[62] There he rendezvoused with the main Stevens survey party on September 30, 1853.[67][68][lower-alpha 10]

Fall of 1853 exploration of the Bitterroot Valley

On October 6, 1853, Mullan traveled from Fort Owen north to the mouth of Hellgate Canyon, where he rejoined Stevens (who had moved there some days earlier).[69] The railroad survey was now over budget and behind schedule, and Stevens still needed to take up his duties as Territorial Governor in the territorial capital of Olympia. Stevens resolved to proceed further westward, while assigning Mullan the task of mapping western Montana with the goal of determining the best route for a railroad. Mullan was also to take meteorological observations, gather data on river and stream flows, find the headwaters of the Missouri River, and gather as much statistical data on population, wildlife, timber, agriculture and geology as he could.[68]

On October 8, Mullan left Fort Owen for a spot about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) north-northwest of present-day Corvallis, Montana. He and 15 men set up a camp here in just seven days, erecting two barns, a corral, and four log cabins. Mullan named it Cantonment Stevens.[70] On October 15, he and guide John Owen (owner of Fort Owen) set out to explore the southern end of the Bitterroot Valley and then proceed southward to find their way to Fort Hall (near present-day Pocatello, Idaho). But Owen lost his way after just a few days, and the two returned ignominiously to Cantonment Stevens.[70] In November, Mullan, accompanied by five men,[lower-alpha 11] explored the Bitterroot River to its source, crossed the Sapphire Mountains and Anaconda Range, and explored the Big Hole River north and west to the Jefferson River.[71] Returning to the Missoula Valley, from November 28 to December 13 he retraced his route to the Big Hole River, followed it south to its headwaters, then crossed the Beaverhead Mountains to enter modern-day Idaho. Passing south via the valley between the Beartooth Mountains and the Lemhi Range, he reached Fort Hall on December 13.[72]

On December 19, he struck north again, retracing his path.[73] He crossed Monida Pass,[73] then turned east after crossing the Beaverhead Mountains, passing through a broad prairie between the Pioneer Mountains and the Ruby Range. He followed the Beaverhead River to the Jefferson River again, then explored the Gallatin Valley before turning west to the Big Hole River again. Turning north, he followed a stream until he reached a series of low ridges which divided the Big Hole tributary from the Hellgate Fork of the Bitterroot River. Crossing these, he arrived at the headwaters of the Deer Lodge River (now known as the Clark Fork River) on December 31. He followed the Deer Lodge River to the Hellgate Fork, and retraced his path back to Fort Owen, which he reached on January 10.[74] Mullan and his men had traveled through heavy snows and strong winds that drove the wind chill tens of degrees below zero, crossed rivers and streams covered in thin ice (through which their horses frequently plunged), and often went hungry.[75] They had crossed the Continental Divide four times in the dead of winter, had identified two wagon routes from Fort Hall to Fort Owen, and seen Beaverhead Rock (which, in 1805, had told the Lemhi Shoshone teenage girl guide Sacagawea that she and the Lewis & Clark Expedition were near her homeland).[76] In 45 days, he had traveled more than 700 miles (1,100 km).[77][78]

Blazing the Fort Benton-Mullan Pass road

In February 1854, Mullan learned from Native Americans of a much better pass between the Missoula Valley and the Helena Valley.[79] On March 2,[79] he left the Missoula Valley with five men, one of whom was Private Gustav Sohon.[80] Mullan retraced his route along the Little Blackfoot River and over "Hell Gate Pass", and followed the Missouri River north to Fort Benton, which he reached on March 12. Obtaining soldiers, wagons, and supplies, he departed on March 14 and scouted out a level prairie road from Fort Benton to the confluence of the Sun and Missouri rivers (at present-day Great Falls, Montana). Rather than follow the route taken by Stevens a year earlier, he stuck to the Missouri River, which offered a flat road at least to the Dearborn River. He then decided to strike inland rather than keep to the river, and discovered a wide, flat prairie about 15 miles (24 km) west of the river. This allowed him to skirt the rugged Adel Mountains Volcanic Field. He then followed the valley of Little Prickly Pear Creek back to the Missouri River. On March 21, he camped on Prickly Pear Creek in the foothills of the Lewis and Clark Range. Following Tenmile Creek and then Austin Creek, he discovered and then crossed Mullan Pass.[33][80][81][82][83]

After taking Mullan Pass over the Continental Divide, he regained the valley of the Little Blackfoot River and reached the Missoula Valley on March 28. Although the Mullan route was 40 miles (64 km) longer than the Stevens/Donelson route over Cadotte Pass discovered in 1853, Mullan Pass had a gradual ascent and descent over only lightly wooded country that made it nearly perfect for the construction of a wagon road.[66] Mullan had also crossed the pass in winter but encountered no difficulty with wagons.[80] The importance of the Mullan Pass was immediately recognized by the press.[80]

Exploring the Flathead Valley

Mullan now sought a route west out of the Flathead Valley to the plains of eastern Washington.[84] On April 14,[85] Mullan left Cantonment Stevens with four of his best men: Thomas Adams, W. Gates, Gabriel Prudhomme, and Gustav Sohon.[84] Mullan followed the Clark Fork to its confluence with the Flathead River. His party built rafts to cross the Flathead, and emerged onto Camas Prairie[85] on April 17. The party spent the night with the Kalispel Indians, traveled north for two days, and spent the night with a band of Yakama led by Chief Owhi.[84] Following the Flathead River again,[85] the party reached Flathead Lake. Mullan's group traveled 40 miles (64 km) north of the lake to try to find a way west, but could not. They turned south again on April 27.[86]

The party built a bridge to cross the Tobacco River, and were forced to swim a tributary of the Tobacco at another point.[87] A Ktunaxa (Kootenai) Indian offered them hospitality on April 29 as the group followed the Tobacco River to its headwaters near the modern town of Fortine, Montana.[88] A day later they met Michael Ogden, a Hudson's Bay Company agent who had established a temporary trading post in the vicinity of modern-day Kalispell, Montana. Resting with Ogden for a day, the party continued south back to Cantonment Stevens accompanied by an Indian woman and her children.[87] Reaching Camas Prairie, Mullan followed Hot Springs Creek to its source, rediscovering a series of hot springs near present Hot Springs, Montana, which Lewis and Clark had previously visited.[89] Continuing to Cantonment Stevens, on May 4 the Mullan party found its way barred by the Clark Fork River.[lower-alpha 12] Two rafts were built in an attempt to cross the river, which was swollen with spring runoff. Prudhomme, riding his horse, crossed the river safely while guiding the other horses and towing one raft. But Mullan's raft, with the remainder of the group, was swept downstream. Mullan was cast adrift when the raft struck a snag, and may have been killed by flotsam if his men had not abandoned their rafting poles to save him. Mullan now ordered Adams, Gates, and Sohon to strip naked and swim for shore, towing the raft behind them. The raft, now 2 miles (3.2 km) downstream, passed a rocky island. The men swam for the island, and pulled the raft close. Mullan's party now tried to save their supplies, and got most of them on the island before the raft broke free and disintegrated. Adams swam to the opposite shore through icy water, and made his way (still naked) to Prudhomme. Prudhomme then helped rescue the party and the supplies using the horses.[92]

After nearly losing the party, Mullan's group arrived back at Cantonment Stevens on May 5.[89]

Final explorations

.jpg.webp)

With Native Americans either unwilling to talk, purposefully deceitful, or too unfamiliar with wagon travel to offer good advice, Mullan still needed to determine which of the remaining passes known to white explorers would be the best for a planned railroad or wagon road. On May 21, Mullan set out with a small party on horseback, following the Clark Fork. Reaching Lake Pend Oreille, the group abandoned their horses and canoed across the lake and down the Pend Oreille River to the St. Ignatius Mission near modern-day Cusick, Washington.[93][94] A messenger was sent to John Owen, who had relocated to the Spokane Valley, asking him to send horses to the mission. Meanwhile, Mullan and the remainder of his group traveled northwest about 30 miles (48 km) to Fort Colville, a Hudson's Bay Company trading post located at Kettle Falls on the Columbia River. After purchasing supplies, the party returned to St. Ignatius.[93] Consulting with Native Americans living at St. Ignatius,[95] Mullan's group then went south to the Spokane Valley, and returned east by following the Coeur d'Alene River into the mountains and crossing Lookout Pass back to the Bitterroot Valley and Cantonment Stevens.[96] Mullan reported to Stevens that flooding on the Pend Oreille route rendered it less feasible than the Lookout Pass route.[95]

Mullan then explored the last remaining route for a roadway: Following Lewis and Clark's trail over Lolo Pass.[95] Mullan and his party left on September 19, leaving the Bitterroot Valley by cutting westward where Lolo Creek meets the Bitterroot River (near present-day Lolo, Montana). For 20 miles (32 km), the wide Lolo Creek Valley provided easy going. The route over Lolo Pass, however, was steep and blocked by much fallen timber. The party passed Lolo Hot Springs (first identified by Lewis and Clark), and then followed the Lochsa River to the Middle Fork of the Clearwater River (then called the Kooskooskia) and the way out of the mountains. After 11 days of very difficult travel,[97] Mullan's group emerged onto the Weippe Prairie and continued following the Clearwater—intent on following it until it reached the Snake River. From there, the party could easily orient itself and travel to Fort Walla Walla.[98] About 20 miles (32 km) from the Clearwater's confluence with the Snake, Mullan's group struck south up the valley of Lapwai Creek.[99] After a few miles, he came upon the farmhouse of noted fur trader and frontiersman William Craig. Craig, his wife, and the local Niimíipu (or Nez Perce) people fed the group fresh vegetables, the first the group had eaten in 21 months. Mullan's party spent the night at the Craig farm, and then cut overland west to Fort Walla Walla.[100] The party reached Fort Walla Walla on October 9, and then Fort Dalles on October 14. Having surveyed all known routes, Mullan wrote a final report to Stevens advising that the future military road utilize Lookout Pass. He was then discharged from the Stevens survey party, and returned to Army authority.[99]

Interregnum of 1855 to 1858

Mullan proceeded to Olympia, the capital of the Washington Territory, in December 1854, where he joined Stevens and other members of the Stevens survey party in writing reports about the survey mission. Mullan and Stevens became close friends, and Stevens sent Mullan to Washington, D.C., with letters and proposals to build a military road from Fort Benton to Fort Walla Walla.[101] When he reached Washington in January 1855, Mullan learned that Congress had appropriated $30,000 ($977,111 in 2022 dollars) to build a military wagon road from the confluence of the Platte and Missouri rivers in the Nebraska Territory to the military road leading from Fort Walla Wall to Olympia. Secretary of War Davis, however, refused to spend the money, noting that the appropriation was far too little to build the road.[102]

Mullan attempted to convince Davis to authorize the expenditure of funds, but was not successful.[103] On February 28, the Army promoted Mullan to 1st Lieutenant and ordered him to report to his unit, Company H of the 2nd Artillery Regiment.[34][lower-alpha 13] The regiment was stationed in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, which was at that time in the grip of a long yellow fever epidemic, and three officers of the regiment had died. Mullan did not immediately report to duty, and Company H listed him as absent without leave.[104] Mullan finally reported for duty in late July, and on July 27 applied for a transfer to the Corps of Topographical Engineers.[105] His request was denied.[106]

Seminole War

The Third Seminole War broke out in Florida on November 20, 1855.[107] A wide range of sources, including George W. Cullum's Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy,[34] the unpublished memoirs of Rebecca Mullan,[108] the American National Biography,[109] frontier historian Dan L. Thrapp,[110] and Montana historians Edwin Purple and Kenneth Owens,[111] all claim that Mullan spent time in Florida fighting in the Third Seminole War—some claiming as much as two years.

But Mullan biographer Keith Peterson has argued that Mullan spent no time in Florida, or at most a few weeks. Peterson notes that Mullan remained in Louisiana with Company H until at least January 1856, when he was ordered to report to Company A at Fort McHenry in Baltimore, Maryland. Mullan did not report to Company A until March 5, so it is possible that he spent part of January and February in Florida. But if so, there are no Army records of it and his time there would be brief at best. Mullan was detached from Company A in May and June 1856, but this would have left him almost no time to travel to and fight in Florida. He returned to Company A in early July 1856, and remained there until Company A was transferred to Fort Leavenworth in the Kansas Territory. He remained in Kansas until December 1857, when he was transferred to Washington, D.C., to work with Isaac Stevens again.[112]

Approval of the Mullan Road

Convinced that Native American attacks and additional settlement of the area could be achieved only by having a military road built, Isaac Stevens resigned as Washington Territory's governor and was elected its congressional delegate in July 1857.[113] Stevens moved to Washington, D.C., and began pushing for money to build the Fort Benton-Fort Walla Walla road. Although it is unclear if Stevens actually made the request, in late 1857 Mullan was detached from Company A and ordered to the capital to assist Stevens with his efforts.[114]

With the need to move military personnel and supplies from Fort Walla Wall into the interior due to the ongoing Yakima War and the emerging Utah War (between the U.S. government and Mormon settlers) ever more apparent, on March 15, 1858, the War Department issued orders for construction of the Fort Benton-Fort Walla Wall Road.[lower-alpha 14] Mullan was ordered to report to Fort Walla Walla and supervise the effort.[116][117] The War Department relied on the legal authority and $30,000 appropriation provided for in 1855 to begin the work.[117][118]

Coeur d'Alene War

Mullan believed he could complete the military road by December 1858.[115] Mullan departed New York City on April 5,[119] bound for Panama. After crossing the Isthmus of Panama, he boarded the sidewheel paddle steamer Sonora and arrived in San Francisco on May 1. Traveling by coastal steamer,[120] he reached Fort Dalles on May 15,[119] accompanied by civilian topographical engineers Theodore Kolecki and P.M. Engle. At the fort, Mullan met and employed Gustav Sohon, now a civilian as well.[121][lower-alpha 15] Mullan organized and outfitted a work party of 30 civilians,[123] and began work on the road. They graded the flat prairie and had reached Five-Mile Creek (about 3 miles (4.8 km) from the fort) when word reached Mullan and Colonel George Wright (commander of Fort Dalles) that Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Edward Steptoe had been routed by a group composed primarily of Cayuse, Schitsu'umsh, Spokan, and Yakama warriors at the Battle of Pine Creek (near present-day Rosalia, Washington) on May 17, 1858.[124] The Schitsu'umsh were outraged by miners and illegal white settlers invading their territory. Although their lands were protected by treaty, they perceived the construction of the Mullan Road as a precursor to a land-grab by the United States.[125]

The Coeur d'Alene War had begun.

Realizing work on the road could not continue if Native American hostilities were under way, on May 27,[126] Mullan sent word to Steptoe (stationed at Fort Walla Walla) asking for 65 soldiers to escort his road-building crew as they worked toward the Rocky Mountains.[123] While he waited for a reply, Mullan's men bridged Three-Mile Creek and Five-Mile Creek. On May 30, Steptoe responded that he could not fulfill Mullan's request.[124] Mullan was forced to disband his road-building crew, retaining only Kolecki, Sohon, and a few men to care for the horses and mules.[127]

Seeking the enemy

Mullan immediately volunteered to serve under Col. Wright, whom the War Department had designated commander of the retaliatory effort.[127] Brevet Brig. Gen. Newman S. Clarke, commander of the Department of the Pacific, ordered Wright to not only punish the tribes severely but to make any surrender conditional: Mullan must be allowed to build his road without being molested in the slightest.[128] Realizing no work on the road could be completed for the remainder of 1858, Mullan wrote to the War Department on June 21, asking for an additional congressional appropriation for road construction. On July 14, Mullan—accompanied by Kolecki, Sohon, three employees, and a Native American boy—left on a nine-day journey to Fort Walla Walla.[129] Wright signed a treaty with a faction of the Niimíipu (Nez Perce) on August 6, in which they agreed to fight alongside the U.S. Army against the other tribes.[130][131] On August 7, Capt. Erasmus D. Keyes led a column of 700 men out of Fort Walla Walla, heading for the confluence of the Snake and Tucannon rivers (about 60 miles (97 km) north of the fort).[132][130] The group included 200 civilian pack-train workers, 30 Niimíipu in Army uniforms, two 12-pound (5.4 kg) howitzers, and two 6-pound (2.7 kg) cannon.[132][131][lower-alpha 16]

The column reached its destination on August 10, and began construction of Fort Taylor. Keyes had instructions to cover the mouth of both the Tucannon and the Palouse River, about 2 miles (3.2 km) down the Snake. Keyes ordered Mullan to clear a path through the shoreline brush to allow easy travel to the mouth of the Palouse. The work was proceeding on August 11 when Mullan's men captured two Native Americans. One escaped and plunged into the Snake River. Mullan gave chase into the water, firing his pistol. The other man rose up out of the water, hurling rocks at Mullan. The two men grappled with one another, the much stronger Native American overpowering Mullan and nearly drowning him. Mullan survived only because the other man stumbled into a hole in the riverbed, which separated the two. The Native American swam to the opposite shore and escaped.[134][135]

Having been joined by Wright, the column crossed the Snake on August 25 and 26.[136] It took three days to pass through the Channeled Scablands.[137] On August 30, at about 5 P.M., a small band of Native Americans on horseback approached Wright's encampment and fired on the troops. Mullan and his Niimíipu gave chase and almost caught up to them before an Army bugler called them back to camp. The following day, Mullan and his scouts became separated from the main column while deep in enemy territory. Only with great difficulty did they evade numerous patrols and detection before rejoining Wright.[138]

Battle of Four Lakes and Battle of Spokane Plains

On September 1, 1858, Mullan participated in the Battle of Four Lakes (near present-day Spokane, Washington). At the start of the battle, he led his Niimíipu scouts on a flanking attack on the Native American left, driving them from the ridge which they occupied. He won extensive praise from Wright for his actions.[139]

Wright rested his men for three days, and on September 5 moved out again to the north.[140] The Native Americans had rallied, however, and now 500 to 700[141][142] warriors began a series of hit-and-run attacks on the column.[143] After about 14 miles (23 km), Wright's group reached a small wooded area. The Native Americans set fire to the prairie and began using the smoke for cover as their attacks intensified.[144] Wright now turned east-northeast to the Spokane River where, with the water at his back, he could more effectively concentrate his fire and protect his men.[141] To clear the way, Wright ordered Mullan and his 30 Niimíipu scouts to race through the smoke and scout the land ahead to ensure the column was moving in the right direction.[143] They did so repeatedly for the next eight hours. To protect the column as it moved, Wright ordered three companies to move forward in a skirmish line to the front and right, breaking up the Indian attacks.[141] They were followed by Wright's cavalry, which charged into the disordered enemy and scattered the warriors.[143] Whenever Native Americans attempted to regroup in the forest to Wright's left, the howitzers and cannon would rake the trees.[145] By nightfall, the column had reached the river and the Native American combatants had fled. Only a single soldier had been slightly injured, even though the column had come 25 miles (40 km) through a near-constant barrage of gunfire.[144]

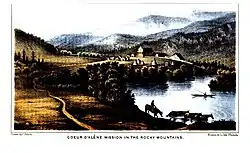

The column reached the Coeur d'Alene Mission on September 15.[146] The Schitsu'umsh chiefs signed a document of surrender on September 17, [147] followed by the Spokan on September 27.[148] On September 23, Mullan joined a unit under the command of Major William Grier in retrieving the bodies of soldiers who died at the Battle of Pine Creek.[149]

Mullan had requested permission in June to travel to Washington, D.C., to confer with the War Department and members of Congress so that additional funds might be procured for the military road. On September 30, a messenger reached Wright's column with orders directing Mullan to proceed to Fort Vancouver near the mouth of the Columbia River and await instructions. Mullan left Wright's party on October 2, and arrived in Vancouver on October 9.[149]

Construction of the Mullan Road

Winning more funds

Rather than wait at Fort Vancouver as instructed, Mullan departed for the East Coast almost immediately, taking Kolecki with him.[150] He took a steamer from Fort Vancouver to Panama, crossed the isthmus, and took a second steamer to New York City. He then traveled by train to Annapolis, where he stayed with his parents and pleaded illness as a reason for delaying his trip to the capital.[151] Mullan escaped punishment, in part, because Isaac Stevens had returned to Washington as well. He needed Mullan to help win passage of additional funds for the road, and so protected him from Congress. Additionally, Jefferson Davis had returned to Congress, too. Davis had long wanted more money for the road, and with Secretary of War John B. Floyd in complete agreement a new appropriation seemed likely. So Davis, too, protected Mullan from Army wrath. Finally, even the Army realized that a military road was now critical, so that troops in the field no longer had to rely on long, vulnerable pack trains. Having Mullan available to support more money for a military road met with Army wishes as well.[152]

Mullan ventured to Washington, D.C., in December 1858.[153] The second session of the 35th United States Congress had opened on December 6, and the Army appropriations bill (H.B. 667) for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1860, was under consideration. In late December 1858 or early January 1859, Jefferson Davis drafted an amendment to the bill, approving $350,000 for a military road from Fort Abercrombie (on the North Dakota–Minnesota border) to Seattle. On January 20, 1859, Secretary of War Floyd sent a letter to Davis endorsing the amendment. He followed this with a letter on February 24, in which he said that, if Congress would not appropriate the full amount, then it should consider appropriating $200,00 for a road from Fort Benton to Fort Walla Walla. If Congress desired, it could split the appropriation between two fiscal years, he wrote. On February 26, 1859, Davis offered an amendment on the floor of the Senate during a debate on H.B. 667 by the Committee of the Whole. Davis' amendment appropriated $100,000 for the road, and was adopted on a voice vote.[154] In the House, Davis' original amendment for $350,000 was reported unfavorably by the House Committee on Ways and Means. But Isaac Stevens reintroduced the Davis amendment on the House floor during consideration by the Committee of the Whole. Representative Charles J. Faulkner (D–Virginia) moved to have the bill amended to permit a first fiscal year expenditure of only $100,000. Faulkner's motion passed, 75 to 44, on March 1.[155][156] President James Buchanan signed the bill into law on March 3.[157]

Mullan and Kolecki spent most of March gathering information on road-building from other military officers and civilians who had done so out west; ordering equipment; sending out orders for a larger civilian work crew, including several more highly educated and trained men like Kolecki and Sohon; asking the military for an escort for his work crew; and seeking funds so he could obtain gifts for Native Americans.[158]

Before leaving for the West Coast, Mullan became engaged to Rebecca Williamson of Baltimore. She was the granddaughter of Luke Tiernan, a politically well-connected and wealthy businessman who had helped win a state charter for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The two most likely met in 1856, when Mullan was stationed at Fort McHenry.[159]

Building the road: 1859

Mullan left Baltimore on March 31, and New York City on April 5. Traveling by steamers and again crossing the Isthmus of Panama, he reached Fort Dalles on May 15, 1859.[160] He now hired more than 80 civilians as his road construction crew, including his own brothers Louis (a drover) and Charles (a physician), and his future brother-in-law, David Williamson. The crew included carpenters, cooks, herders, laborers, teamsters, and topographers. The Army provided an escort under the command of Lt. James White. White's troop consisted of 100 soldiers and 40 packers and teamsters. Mullan also acquired 180 oxen and dozens of cattle, horses, and mules, and hired famed wagon master John Creighton to organize his pack train. To scout the route ahead, Mullan relied on Kolecki, Sohon,[161] and Engle,[162] as well as a new topographer, Walter W. DeLacy.[161]

Scouting of the route began on May 16,[163] and Mullan lead the work crew out on July 1. The road headed north to Fort Taylor, where the Snake River was crossed with pontoon boats. One man drowned during the crossing.[164] After crossing the Snake, the crew began leaving wooden mile markers, sometimes also inscribed with information about distance to the nearest water or other useful information. An old branding iron with the letters "M" and "R" on it was used to inscribe each marker. Mullan intended the initials to mean "Military Road", but the crew began using them to mean "Mullan Road".[165] The crew also made the first longitudinal observations north of 42 degrees latitude, and made maps of the territory which remained the best for another 50 years.[166] In mid-July, the crew reached Lake Coeur d'Alene. Mullan decided to build the road on the shortest route past the lake, which was along the southern edge. Unfortunately, this meant a rapid, 700-foot (210 m) descent into the Valley of the St. Joe River, and then an extremely difficult passage through dense timber and heavy underbrush. Massive, fallen trees blocked the route every few feet, and boulders, some of them half-buried, had to be blasted or rolled out of the way. It took eight days just to reach the valley floor.[167] Mullan then encountered a large swamp, which his crew bridged with a corduroy road. Reaching the 240-foot-wide (73 m) St. Joe River, the crew built two flat-bottomed boats to serve as a ferry, since building a bridge was not practical. The work crew reached the Coeur d'Alene Mission on August 16, having blazed 198.5 miles (319.5 km) of road.[168]

Resting his men at Coeur d'Alene Mission, Mullan sent Gustav Sohon ahead to scout a path into the Bitterroot Mountains.[168] While waiting for Sohon's report, one of Mullan's men discovered gold. Mullan swore to secrecy the few individuals to learn for the find, and informed the War Department by letter.[169] Sohon discovered St. Regis Pass, although Mullan named it "Sohon Pass" in honor of his friend. Moving forward toward Sohon Pass, Mullan again found the timber incredibly dense, and the trees very large in diameter. To speed up the road-building, he sent 23 men about 11 miles (18 km) ahead to the east, and then his two crews worked toward one another. Following the Coeur d'Alene River into the mountains, Mullan's crew was forced to build approximately 50 to 60 bridges across the twisting river.[170] It rained throughout October. On November 3, 15 to 18 inches (38 to 46 cm) of snow fell. Snow fell for a week, and then the temperature dropped below 0 °F (−18 °C). Food supplies dwindled, and the supply train with winter clothing was delayed.[171] Having cut the road through roughly 80 miles (130 km) of forest and mountains, Mullan's crew called a halt near modern-day De Borgia, Montana, and constructed residential huts, a log cabin office, and a storehouse. A stockade and four blockhouses protected what was called Cantonment Jordan. Most of Mullan's cattle, horses, and mules died; what few cattle survived, the men butchered. A few men were detailed to herd the remaining horses and mules to the Bitterroot Valley, where temperatures would be warmer and the snow much less deep. None of the animals survived the 100-mile (160 km) trek.[172] Although the supply train with winter clothing and more supplies eventually reached Cantonment Jordan, it had to leave 10 short tons (9.1 t) of supplies at the foot of the pass because the exhausted animals could not continue. Mullan had his men build 20 sledges, and they manually hauled the supplies to the camp.[173]

The winter was incredibly harsh. On December 5, the temperature plunged below −40 °F (−40 °C).[174] The snow was 5 feet (1.5 m) deep in December, and 7 feet (2.1 m) deep in January.[175] Frostbitten feet were common. Despite the incredible hardship, Mullan kept his men working with little complaint. Historian Keith Petersen calls this Mullan's "greatest accomplishment".[173] About 25 of the soldiers came down with scurvy, after eating too much salted meat and too few vegetables. Mullan had vegetables transported from the Coeur d'Alene Mission, and convinced the soldiers to eat them and less salt meat. The plague of scurvy ended.[176]

Building the road: 1860

In order to avoid complete isolation from the world, Mullan paid two of his men to travel back and forth to Fort Walla Walla with mail. Mail arrived twice a month, once a month in bad weather. Another man was sent to Salt Lake City, Utah Territory, to buy replacement mules,[lower-alpha 17] while P.M. Engle was sent to Fort Benton to buy cattle and supplies.[177] In early January, Mullan sent engineer Walter Whipple Johnson to back to Fort Walla Walla with instructions to proceed to Washington, D.C., and dispel rumors that the road crew was in crisis. During the winter, Mullan also reassessed his route. He realized that his road should have followed the north shore of Lake Coeur d'Alene and the Clark Fork River.[178][lower-alpha 18] Significantly over budget, Mullan told his crew that he might not be able to pay their wages. Five left.[180]

In Washington, D.C., a struggle was under way to appropriate more money for the Mullan Road. On December 1, 1859, Secretary of War Floyd told Congress of "the existence of great mineral wealth in the mountains through which a portion of the road passes."[181] On January 18, 1860, Senator Joseph Lane (D-Oregon) announced he would submit legislation to appropriate funds to finish the road.[182] The bill (S.93) was introduced the following day and referred to the Senate Committee on Military Affairs.[183] On February 16, Isaac Stevens introduced a companion bill (H.R. 702) in the House, which was referred to the House Committee on Military Affairs.[184] Despite the legislation, in April 1860 Captain Andrew A. Humphreys at the War Department decided to cancel the road, citing Mullan's cost overruns.[169] Johnson arrived in the capital in April just as the appropriation seemed lost, and he and Isaac Stevens began to press for its passage. They received extensive support from Floyd, who was increasingly convinced by Mullan's September report that vast gold deposits awaited in the Rocky Mountains.[185] H.R. 702, which provided $100,000 to complete the road,[186] moved first. The House considered the bill as a Committee of the Whole on May 12, which recommended its passage. Later that day, the House passed the bill on a voice vote.[187] The bill was referred to the Senate, which adopted it on a voice vote on May 23.[186] President Buchanan signed it into law on May 25.[188]

Walter Johnson had a secondary mission as well: To have the War Department send a unit of soldiers over the Mullan Road. This would not only put an end to talk that the road was intended for commercial (not military) use, but also prove the road's value. Johnson successfully convinced Floyd to give the order. Instead of returning to Fort Walla Walla with a letter from Humphreys canceling construction, Johnson returned with a letter from Floyd with the good news about the new appropriation.[189]

Determined to keep the road construction going, on February 20 Mullan sent his civilian workers ahead to the confluence of the Clark Fork and Blackfoot rivers (near modern-day Missoula), where they were to construct a large flatboat ferry and five small flat-bottomed pirogues for use by the construction crew and the route scouts. Mullan ordered the soldiers in his party to begin building the road from Cantonment Jordan to the Blackfoot River as soon as weather permitted.[190] By June 4, the 85-mile (137 km) road had been cut through to the Blackfoot, and Cantonment Jordan was abandoned.[191][lower-alpha 19] Mullan himself left Lt. White in charge on February 26 while he rode to a by-now much-enlarged and prosperous Fort Owen. He spent two weeks resting and waiting for the weather to improve, then began meeting with the Kalispel, a large number of whom wintered in the Bitterroot Valley. His excellent relations with this tribe convinced 17 Kalispel to take 120 horses and accompany Gustav Sohon across the mountains to Fort Benton, and return laden with the supplies which the War Department had shipped there via steamboat. The Indians and Sohon left on March 16, and returned a month later.[193]

Mullan was now running out of time. Major George A.H. Blake was steaming up the Missouri River with 300 men, with the intent of using the Mullan Road to travel to Fort Walla Walla. The road had to be completed by the time he arrived, which meant that Mullan had to speed his work as well as cut corners. Twice floods destroyed his ferries (once nearly drowning Mullan himself), and Mullan was forced to bridge the Blackfoot repeatedly rather than blast and dig through hillsides (which would have meant a shorter route but taken more time). The construction crews reached Mullan Pass on July 18, 1860. The treeless summit and gradual slope to the Missouri River Canyon below signaled the end of the hardest part of the road-building effort. The only difficulty yet remaining was at Tower Rock, where the crew spent four days digging and blasting for four days. The construction crew reached the Sun River on July 28, which meant the end of grading. For the last 55 miles (89 km), the crew merely had to plant mile markers. Mullan completed the Mullan Road on August 1, 1860.[194] He immediately wrote to Captain Humphreys, informing him that the southern route around Lake Pend Oreille was the incorrect one, and asking for funds and permission to reroute the Mullan Road around the north end.[195][196] He then sent Theodore Kolekci downriver, with all his field notes, to deliver them to the Army in Washington, D.C.[197]

The Mullan Road cut through 120 miles (190 km) of dense forest and 424 miles (682 km) of prairie. About 30 miles (48 km) of hillside cuts were dug, as well as hundreds of bridges and several ferries.[198] Blazing the Mullan Road, along with his expedition to the Salish and his exploration of the Bitterroot Valley, gave John Mullan a reputation as one of the preeminent explorers of the day.[45] Mullan "became the equivalent of the great pathfinder for the Inland Northwest", says David Nicandri, historian with the Washington State Historical Society.[198] The Washington Territorial Legislature passed a resolution in January 1861 thanking Mullan for his achievement in building the Mullan Road.[199]

Final military years

On August 5, 1860, Mullan returned west to Fort Walla Walla, making repairs to the Mullan Road as he went. Following behind came Major Blake and his command. Mullan reached the Coeur d'Alene Mission about September 21, and Fort Walla Walla on October 8.[200] Mullan found orders awaiting him at the fort, telling him to remain there during the winter to compile a report. Mullan remained at the fort only until January 1861, when he and Gustav Sohon[201] traveled down Columbia River to Fort Vancouver, took the steamer Pacific to San Francisco, and booked passage on the Butterfield Overland Mail (a stagecoach) overland to St. Louis. The stage trip took 22 days.[202] It's unclear if they arrived in Washington on February 13[202] or February 25.[201]

Rerouting the Mullan Road

.jpg.webp)

With the American Civil War on the verge of breaking out, and Mullan's patron Jefferson Davis having defected to the Confederacy, there was little desire in the Army to spend money on a road in the Washington Territory. Mullan boldly proposed construction of a military road from Fort Laramie (in what is now far southeastern Wyoming) to Fort Walla Walla. This proposal was immediately turned down: Mullan had asked for a rerouting of the Mullan Road in August 1861,[203] and Captain Humphreys had approved this plan on February 7.[204] Mullan remained in Washington for roughly six weeks, and his actions and movements during this period are unknown. There is a record of a meeting with Isaac Stevens, but nothing else. Mullan departed the city in early March[203] and reached San Francisco on April 5.[205]

It is unclear when Mullan reached Fort Walla Walla. Mullan himself claims he did so in early April,[206] but other evidence indicates he arrived on April 22.[203][207] The Corps of Topographical Engineers[lower-alpha 20] had approved of 15 months of work at a budget of $85,000.[207][lower-alpha 21]

Mullan was delayed in beginning work, as the Fort Colville Gold Rush (also known as the Idaho Gold Rush) and the Clearwater Gold Rush made it difficult and expensive to find men and animals.[205] Mullan had proposed (in August 1860) to begin work on April 1,[210] but his late arrival in Washington Territory prevented that. Mullan later proposed departing on May 5,[211] but he did not leave Fort Walla Walla until May 13.[206][210] Mullan set out with a civilian work crew of 60, with 21 soldiers of the 9th Infantry Regiment as a guard. Another 39 soldiers of the 9th Infantry led and guarded the supply train. Due to the risk of Indian attack, another 79 men of the 9th Infantry, under the command of Lieutenants Nathaniel Wickliffe Jr. and Salem S. Marsh, followed a few days later.[205] Mullan reached the Snake River on May 20, and Marsh caught up to him on May 23.[212] By June 4, the work crew had regraded and repaired about 156 miles (251 km) of road, and had reached the farm and ferry of Antoine Plante on the Spokane River.[210] Lt. Charles G. Harker from Fort Colville arrived with more men,[212] and Mullan's civilians and soldiers began cutting through dense timber north of Lake Coeur d'Alene on June 5. To ensure that they could not get cut off if Native Americans attacked the long supply route, the party built two supply depot storehouses as they worked east into the Rocky Mountains. They reached the top of the pass (Fourth of July Summit) on July 4, having cut just 6.5 miles (10.5 km) through the thick forest.[213][214][lower-alpha 22] They added another 5.5 miles (8.9 km) by July 14.[209] The party reached the Coeur d'Alene Mission on July 31, a month behind schedule.[216] Mullan now learned of the loss of the steamer Chippewa due to fire and explosion at the confluence of the Poplar and Missouri rivers.[217][218] The steamer was transporting Mullan's supplies, which meant Mullan now had to send riders back to Fort Walla Walla to purchase far expensive supplies in the town.[217] On August 11, 1862, while Mullan was slowly cutting his way through the dense timber of the Bitterroot Mountains, the War Department promoted him to Captain.[219] On August 13, Mullan dispatched Lt. Marsh with 50 soldiers and civilians to lightly repair the road ahead, with an eye to moving supplies into the Bitterroot Valley for the winter camp.[220] Three days later, the party reached the 222-mile (357 km) marker on the Mullan Road.[210]

Snow began falling on November 1, and Mullan ordered Lt. Marsh to take the supply train and its escort to the confluence of the Clark Fork and Blackfoot rivers, and establish another supply depot.[221] A messenger reached Mullan on November 4, ordering the troops to return east. But with heavy snow already falling, Lt. Marsh knew he could not risk any travel.[222] The work crew reached the depot on November 22. Mullen now established five work-camps for several miles along the Clark Fork, each camp located where extensive digging was needed so that excessive crossing of the Clark Fork could be avoided.[221] The depot and work camps were collectively named Cantonment Wright.[223] The animals were driven south toward Cantonment Stevens and the Bitterroot Valley, where Mullan hoped the temperatures would be more moderate and the snow less deep.[221] By December 1, daytime temperatures were far below 0 °F (−18 °C), with one of the worst winters ever recorded in the area now beginning.[222] Strong winds whipped through the valley.[224] Most of Mullan's animals died from starvation and cold, forcing the men to retrieve supplies from the depot with man-drawn sledges. The cold became so severe for two weeks in mid-January that all work stopped.[225] Mullan spent December 23 to December 27 at John Owen's cabin, and Mullan delivered the first public lecture in Montana state history there on Christmas Day.[226] During the winter, Mullan's men built a four-span bridge across the Blackfoot River[225] and dug and blasted nearly seven miles of cut-outs along the banks of the Clark Force.[224]

The winter proved so harsh that Mullan's party could not move out again until May 23, 1862.[224] With little repair work left to do, the crew reached Fort Benton on June 8.[227] Mullan returned to Fort Walla Walla on August 13.[228] By this time, citizens of the Washington Territory were debating new legislation to reorganize their territory in anticipation of statehood. Some wanted the new territory to incorporate what is now Washington state, the Idaho panhandle, and western Montana, with the capital moved to Walla Walla from Olympia. But others felt the territory's border should extend no further west than the Oregon border, with the northern and southern Idaho mining districts in a new territory and the remainder of the old territory lumped into a new, third territory. Mullan met with Walla Walla's community leaders before departing, and became convinced that the first option was the best.[229] Mullan disbanded his work crew, sold what little stock remained, and departed for Washington, D.C., on either September 7[230] or September 11.[231]

Mulland took Gustav Sohon with him, and in October 1862 made the difficult stagecoach journey from San Francisco to St. Louis again.[232] Mullan found working at the Topographical Engineers difficult. He wanted to work from home, but was forced to work in an office. He hired staff to assist him without authorization, tried to include extraneous material in his report, and began pressing for new funds to rebuild part of the Mullan Road. An exasperated department ordered him to complete his report as swiftly as possible.[233]

Territorial politics

Representative James Mitchell Ashley was chair of the House Committee on Territories, and an advocate of geometric (e.g., square) borders for western states. Ashley quite naturally sought out Mullan as an expert on the region, seeking his advice on how to reorganize the Washington Territory. In mid-December 1862, Mullan drew a proposed territorial border that included present-day Washington state, the Idaho panhandle, and western Montana. Another new territory, which Mullan titled "Montana", awkwardly consisted of southern Idaho and eastern Montana.[234][lower-alpha 23]

Ashley introduced H.B. 738 on December 22, 1862, to reorganize the Washington Territory and form the new Montana Territory. It passed the House easily on January 12, 1863.[235] Throughout 1863, Mullan spent a large amount of time lobbying the Senate to adopt the Ashley bill. Mullan also proposed that he be named governor of the new "Montana Territory", and not only lobbied for the position but collected a large number of endorsements from Senators, Representatives, Territorial Delegates, executive branch officials, and even a Supreme Court justice.[236] But William H. Wallace, Washington Territory's congressional delegate since March 1861, favored much smaller territorial boundaries. To block Ashley's bill, Wallace introduced legislation in the Senate which differed only on minor technical issues. Congress did not appoint a conference committee, and both bills languished until March 3, 1863—the last day of the final session. Wallace now pressed the Senate to adopt a new bill, one which changed Washington Territory's boundaries to his preferred borders and established the remainder as the new Idaho Territory. Ashley was outraged, and demanded a conference committee to reconcile the bills. By now, it was nearly midnight, and exhausted members of Congress refused. At 2:00 AM on March 4, the House took up the second Senate bill and adopted it overwhelmingly. President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill into law near dawn.[235]

Alarmed by Wallace's maneuvering, Mullan now acted to secure appointment as Idaho Territory's territorial governor. He delivered his letters of recommendation to Lincoln on the morning of March 4, just hours after the territory was established. Three of Mullan's Senate supporters then met with the president on the morning of March 5 to advocate for his appointment. But Wallace was a friend of Lincoln's, and he, too, had been lobbying for the position and collecting letters of recommendation. Mullan was a Democrat, and Wallace a Republican. Lincoln nominated Wallace as the first Territorial Governor of Idaho Territory, and the Senate approved the nomination on March 10.[237]

Resignation from the Army

Mullan had long planned to use his Army connections as a means of making money. He had purchased property and owned businesses in Walla Walla, and intended to return there to settle down and use his Army experiences in earning a fortune.[238]

On April 4, 1863, John Mullan resigned from the U.S. Army.[239] Although losing the governorship of Idaho Territory embittered Mullan, it was only one of many reasons why Mullan saw his Army career ending: He disliked Army rules and regulations, he was eager to make money for himself and his family, and he already had business interests in Walla Walla.[238]

Mullan married Rebecca Williamson on April 28, 1863.[240][241]

Business ventures

Walla Walla Railroad

As he worked on his report for the Army in 1862, Mullan began arranging for his post-Army business career.[242] In 1861, Mullan's 23-year-old younger brother, Louis, agreed to become one of 33 incorporators for a 30-mile-long (48 km) railroad from Walla Walla west to Wallula, bypassing rapids on the Columbia River.[243][244][lower-alpha 24] The territorial legislature adopted legislation approving the railroad's charter on January 28, 1862.[254][lower-alpha 25] Louis undoubtedly contacted John about the railroad some time in 1862. About October, John sent a letter to the incorporators. In the letter, read at a public meeting in Walla Walla on December 31, John Mullan declared that the company could raise $250,000 to $300,000 to build the railroad. The incorporators were highly enthused, and appointed "commissioners" to raise and receive funds at the end of the meeting.[257] On January 1, 1863, John Mullan sent a notice to railroad industry journals announcing the existence of the railroad venture and calling for investors.[244] Bylaws for the corporation were adopted on March 14, 1863.[258]

On March 28, 1863, Mullan agreed to be a commissioner of the nascent railroad.[256]

After his marriage, John and Rebecca Mullan traveled to New York City.[241] Mullan delivered a lengthy address on eastern Washington, northern Idaho, and western Montana before the American Geographical and Statistical Society on May 9.[259] While in the city, Mullan met with some of the incorporators of the railroad company.[260]

The state-approved charter required a route for the railroad to be surveyed by November 1, 1863, and for the road to be open by November 1, 1868.[244] The railroad venture never went forward after steamship companies put several large, speedy new ships into service on the Columbia River in the spring of 1863, bringing the price of freight so low that the railroad could not compete.[258][lower-alpha 26]

Walla Walla farm

Mullan purchased several businesses near Fort Walla Wall in spring 1858, anticipating that the fort and surrounding community would become a boom town once his road was finished.[262] Among these were a part-interest in a sawmill and a 480-acre (1,900,000 m2) farm, and full ownership of a livery stable.[263] Mullan sent his then-20-year-old brother Louis to run the businesses, and gave Louis his power of attorney. Mullan's partner sold his shares to Mullan in 1860. By then, Louis had proved incapable of handling the businesses on his own, so Mullan sent his then-24-year-old brother Charles to Walla Walla to assist Louis. Charles proved no more capable than Louis.[264]

John and Rebecca arrived in Walla Walla in August 1863.[241] Mullan discovered that Louis and Charles had been regularly sued for nonpayment of wages and bills, and that the farm, sawmill, and stable were near financial collapse. He also discovered that Louis and Charles were calling themselves "Mullan Brothers" and incurring expenses in John's name. Moreover, Louis had fenced off 160 acres (650,000 m2) of John's farm and claimed it as his own. In September, Mullan's 30-year-old brother, Dr. James A. Mullan, and his 17-year-old brother, Ferdinand, arrived in Walla Walla as well.[lower-alpha 27] James immediately began conspiring with Louis to defraud John. The relationship between John and Louis broke down, and on December 27, 1863, John attempted to evict Louis. Louis sued, claiming he owned the 160 acres (650,000 m2) and that John and Charles were conspiring to sell Mullan Brothers' property without his consent. At trial, James and Ferdinand both claimed that John had promised all the brothers an equal share in the farm and businesses.[266]

By late 1864, John Mullan was bankrupt. He sent Rebecca to Baltimore, and remained in Walla Walla for a few months to sell what possessions he had to settle the few debts he could. Then he, too, returned to Baltimore.[267] Louis gave James a share in the 160-acre (650,000 m2) farm, which they sold after a few years.[268]

Chico stage

Realizing that guidebooks to the West sold well among settlers and businessmen, Mullan decided to turn his 1863 Army report into a book. He worked on the book throughout 1865, publishing the Miners and Traveler's Guide in mid-year.[269]

While he worked on his book, Mullan learned that John Bidwell, owner of the massive Rancho Arroyo Chico in northern California (now the site of the city of Chico), and miner Elias D. Pierce intended to open a passenger and freight stage between Rancho Arroyo Chico and the booming mining town of Boise in the Idaho Territory. Mullan decided to join the venture, and traveled alone to Boise, arriving in mid-1865. Mullan spent about two months helping to improve an existing road between the town and ranch. With Bidwell contributing some used stagecoaches, in August 1865 Mullan led the first group to travel along the newly improved road, arriving in Ruby City (about 40 miles (64 km) southwest of Boise) on September 1. But the new Idaho and California Stage Line lacked the coaches to make regular service possible, and Native Americans bitterly opposed the new road.[270]

In October 1865, Mullan returned east to try to raise funds for the stage line. He lived with his in-laws in Baltimore, and lobbied for a mail contract with the U.S. Post Office Department. With his brother-in-law, L.T. Williamson, on the West Coast, Mullan felt his chances of winning a contract would be better if the route were awarded to Williamson.[270] On March 18, 1866, the Post Office let the contract to Williamson.[271] Mullan now organized a joint-stock company, the California and Idaho Stage and Fast Freight Company, and raised $300,000 in New York and Baltimore to fund the new stage line.[272] Mullan returned to San Francisco in May 1866. He hired between 100 and 200 Chinese immigrants to repair the road and construct stations, built a blacksmith shop in Chico, and purchased coaches and animals. The first stage rolled out just after midnight on July 1, and reached Ruby City three days later.[273]

The California and Idaho Stage and Fast Freight Company soon collapsed. Native Americans, incensed at new white settler activity on their lands, burned several stations and slaughtered a number of horses. Although Mullan persuaded the U.S. Army to station some troops along the line, they proved too few in number. Competition from a newly improved road between Umatilla, Oregon, and Boise (which received a large amount of freight from Oregon Steam Navigation Company steamships on the Columbia River)[273] and from a new road (opened in September 1866) between Boise and Hunter, Nevada (which received a large amount of freight from the Central Pacific Railroad)[274] significantly and negatively impacted Mullan's finances. While obsessively seeking the mail contract, Mullan had offended and irritate several wealthy businessmen (including Bidwell), who were also seeking the contract. Now those businessmen declined to assist Mullan,[273] leaving him $12,000 in debt.[275] Mullan's last stage departed on November 18, 1866.[276]

California land attorney

After the failure of the stagecoach business, John Mullan moved to San Francisco, and Rebecca moved to be with him. John found a job in a local bank. Rebecca, too, found a job at the bank, working as a copyist, and together the two earned $200 to $300 a month.[275] Mullan also spent part of 1867 working for the Surveyor General of the United States.[34] Mullan, who had read widely in law over the past decade, now resolved to become an attorney. After a few months of study, he passed the California bar exam.[277]

Mullan's first major client was the City of San Francisco, which hired him as an engineer and as legal counsel to help plan an expansion of the city's fresh water system. Mullan received $8,000 for this work.[278]

In 1868, Mullan became the managing agent for the California Immigration Association,[279] located at 712 Montgomery Street. In that capacity, he provided settlers with information on how to obtain public land. He opened a real estate office at the same location in 1871, and by 1872 had a legal practice in the same office.[280]

Mullan formed a law firm, Mullan & Hyde, in 1873 with Frederick A. Hyde, a former clerk in the Surveyor General's office. Their association lasted until 1884,[280] and the firm became the largest land speculator in California.[281] When territories become states, the federal government turns over large amounts of federal land to the state. This land is supposed to be sold to the public, and the funds used to support elementary, secondary, and higher education and to support the establishment of the new state government through the erection of public buildings. The California State Land Office was weak and understaffed,[282] however, and Mullan & Hyde soon colluded with the clerks in the land office to steal land.[283] Mullan and his staff were able to view and even remove copybooks, certificates of purchase, and other official documents to which the general public had no access. Mullan & Hyde did so much volume with the land office that the office purchased preprinted envelopes with the firm's name on them.[281] Mullan & Hyde bribed people to file false lands claims,[284] sold illegally obtained land at exorbitant prices, and purchased land without making the legally required down payment.[285]

Mullan & Hyde also stole land using the "in lieu" system. Since land title records were poor, purchasers of public land often found that the land was already owned by a private individual (who sometimes had obtained the land a century or more ago). In such cases, the individual was able to select public land "in lieu" of the sold land, usually from public lands which would not normally be sold. Mullan & Hyde would obtain "in lieu" filings, copy the information and put a dummy name on the form, backdate the form, and then slip the fake form into the state and federal land office files. Purchasers of public land would then discover that even their "in lieu" land had been taken already. Mullan & Hyde became the state's leading firm in stealing "in lieu" land.[286][287]

Mullan also personally profited from the sale of scrip land. Under the Morrill Act of 1862, the federal government agreed to give each state 30,000 acres (120,000,000 m2) of public land for each senator and representative. This land was to be used to support state-run colleges and universities. Ideally, the University of California was to have retained this land as an investment, but the state provided so few funds to the university that it began selling Morrill Act land (known as "scrip land") at low prices.[288] Colluding with public land officials, Mullan purchased large tracts of scip land before it became available to the public, then resold the land at inflated prices.[289]

His unethical and illegal real estate dealings made Mullan a wealthy man,[279] and he was able to retire the debts he had incurred from his stagecoach business.[290] Mullan was fortunate: In February 1904, the federal government indicted Frederick A. Hyde for fraud and conspiracy.[291] Hyde was accused of such widespread fraud that Congress appropriated $60,000 to bring 200 witnesses to Washington, D.C., to testify for the prosecution.[292] The trial lasted four years, the longest trial in the District of Columbia to that time.[293] Hyde was convicted on 42 counts of bribery, conspiracy, fraud, and other charges in June 1908, with the federal government recovering 100,000 acres (400,000,000 m2) of land worth $1 million.[293][294] Hyde was sentenced six months later to two years in federal prison and fined $10,000.[295] He appealed his sentence to the Supreme Court, which declined to overturn it in 1912.[296] Although Mullan escaped prosecution, his reputation was significantly tarnished for the rest of his life.[297]

State agent in Washington, D.C.

In 1878, Mullan approached California Governor William Irwin, offering to seek compensation from the federal government for a flaw in the California Statehood Act. Traditionally, when admitting new states to the union, the federal government agreed to give the state 5 percent of the gross proceeds from the sale of federal land in that state. California's statehood act, enacted in 1850, neglected to include this provision. The state legislature passed a resolution in 1858 asking the federal government to pay, but no action on the resolution ever occurred.[279] Mullan, who had spent a great deal of time in the past five years in the national capital working on his land business, now proposed to represent California in Washington, D.C., to secure these missing funds. In return, the state would pay Mullan 20 percent of the funds he collected. The state legislature passed a resolution authorizing the governor to appoint an agent, and Irwin appointed Mullan on November 1, 1878.[298] The states of Nevada and Oregon, in similar straits as California, had by 1881 also hired Mullan as their agent to seek payment from the federal government.[298][299] The Washington Territory did so as well in 1886.[300]

Mullan did not just work on land claims. He acted as each state's agent on a wide variety of issues, including reimbursement for state expenditures during Indian wars, federal payments to volunteer soldiers during the Civil War, tax overpayments, and indemnities for state underpayments to the federal government. In time, he acted as a kind of lawyer-ambassador, drafting petitions to be presented to Congress and lobbying federal officials.[300] Although Mullan won small settlements for his clients, giving him a solid income, Mullan lived far beyond his means—getting credit and spending money in anticipation of the major payday which awaited him if he could secure the California public lands payment.[301]

California Governors George Clement Perkins and George Stoneman had both reappointed Mullan as the state's agent, and the state legislature had confirmed each appointment. In 1886, however, former California Surveyor General Robert Gardner initiated a campaign to discredit Mullan, accusing him of hiding the true size of the potential federal payment in order to enrich himself. In the spring of that year, former Governor Perkins sent a letter to Mullan, declaring he had made a mistake in appointing Mullan and allowing him so large a fee.[302] Mullan's commission had not yet expired when Governor Washington Bartlett (Stoneman's successor) died in office on September 12, 1887. He was succeeded in office by Robert Waterman, who threatened to revoke Mullan's commission in February 1888. Mullan wrote and published a book in defense of his work, but Republican-controlled news media and Gardner alleged that Mullan's commission had been improperly approved and that the state's congressional delegation could have done the same work at no cost. On January 18, 1889, Waterman revoked Mullan's commission. Mullan believed the Democratic-controlled legislature would reinstate him, and he moved to San Francisco temporarily to fight the charges against him.[303] The state legislature established a commission to investigate the previous appointments, and the commission ruled in 1889 that governors Perkins and Stoneman had acted legally. Although Mullan remained dismissed, he believed he was still entitled to fees already won.[304]

Mullan had obtained federal reimbursement of $228,000 in costs California incurred in raising volunteers during the Civil War. Mullan was due to receive $45,600, but the federal government's check arrived after the legislative commission's 1889 finding. The state declared that Mullan was not entitled to the fee, as payment was made after he had been dismissed. Mullan sued, and the case went to the Supreme Court of California. The court held that the legislative commission had erred; a bill, not a resolution, was needed to effect Mullan's appointment as state agent. Mullan had no legally binding agreement with the state for any fees. Mullan reacted by asking the state legislature to pay him anyway. The state legislature passed a bill authorizing payment in 1897, but Governor James Budd vetoed it. The state legislature passed another bill in 1899, and Governor Henry Gage vetoed it.[304]

California's actions emboldened Mullan's other clients as well. In 1894, Mullan won a $400,000 reimbursement for the state of Nevada and a $350,000 reimbursement for the state of Oregon. Both state legislatures swiftly passed laws requiring the United States Department of the Treasury to issue checks directly to the state, bypassing Mullan and denying him any commission.[305]

Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions