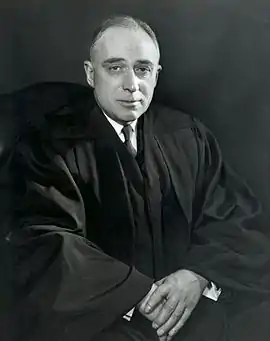

John Marshall Harlan II

John Marshall Harlan (May 20, 1899 – December 29, 1971) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. Harlan is usually called John Marshall Harlan II to distinguish him from his grandfather, John Marshall Harlan, who served on the U.S. Supreme Court from 1877 to 1911.

John Marshall Harlan II | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office March 28, 1955 – September 23, 1971 | |

| Nominated by | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Robert H. Jackson |

| Succeeded by | William Rehnquist |

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit | |

| In office February 10, 1954 – March 27, 1955 | |

| Nominated by | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Augustus Noble Hand |

| Succeeded by | J. Edward Lumbard |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Marshall Harlan May 20, 1899 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | December 29, 1971 (aged 72) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Emmanuel Church Cemetery, Weston, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Spouse |

Ethel Andrews (m. 1928) |

| Children | 1 |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives | John Marshall Harlan (grandfather) |

| Education | Princeton University (AB) Balliol College, Oxford New York Law School (LLB) |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

Harlan was a student at Upper Canada College and Appleby College and then at Princeton University. Awarded a Rhodes Scholarship, he studied law at Balliol College, Oxford.[1] Upon his return to the U.S. in 1923 Harlan worked in the law firm of Root, Clark, Buckner & Howland while studying at New York Law School. Later he served as Assistant U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York and as Special Assistant Attorney General of New York. In 1954 Harlan was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, and a year later president Dwight Eisenhower nominated Harlan to the United States Supreme Court following the death of Justice Robert H. Jackson.[2]

Harlan is often characterized as a member of the conservative wing of the Warren Court. He advocated a limited role for the judiciary, remarking that the Supreme Court should not be considered "a general haven for reform movements".[3] In general, Harlan adhered more closely to precedent, and was more reluctant to overturn legislation than many of his colleagues on the Court. He strongly disagreed with the doctrine of incorporation, which held that the provisions of the federal Bill of Rights applied to the state governments, not merely the Federal.[4] At the same time, he advocated a broad interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause, arguing that it protected a wide range of rights not expressly mentioned in the United States Constitution.[4] Justice Harlan was gravely ill when he retired from the Supreme Court on September 23, 1971.[5] He died from spinal cancer three months later, on December 29, 1971. After Harlan's retirement, President Nixon appointed William Rehnquist to replace him.

Early life and career

John Marshall Harlan was born on May 20, 1899, in Chicago.[2] He was the son of John Maynard Harlan, a Chicago lawyer and politician, and Elizabeth Flagg. He had three sisters.[6] Historically, Harlan's family had been politically active. His forebear George Harlan served as one of the governors of Delaware during the seventeenth century; his great-grandfather James Harlan was a congressman during the 1830s;[7] his grandfather, also John Marshall Harlan, was an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court from 1877 to 1911; and his uncle, James S. Harlan, was attorney general of Puerto Rico and then chairman of the Interstate Commerce Commission.[5][7]

In his younger years, Harlan attended The Latin School of Chicago.[1] He later attended two boarding high schools in the Toronto Area, Canada: Upper Canada College and Appleby College.[1] Upon graduation from Appleby, Harlan returned to the U.S. and in 1916 enrolled at Princeton University. There, he was a member of the Ivy Club, served as an editor of The Daily Princetonian, and was class president during his junior and senior years.[1] After graduating from the university in 1920 with an Artium Baccalaureus degree, he received a Rhodes Scholarship to attend Balliol College, Oxford, making him the first Rhodes Scholar to sit on the Supreme Court.[7] He studied jurisprudence at Oxford for three years, returning from England in 1923.[5] Upon his return to the United States, he began work with the law firm of Root, Clark, Buckner & Howland (which became Dewey & LeBoeuf), one of the leading law firms in the country, while studying law at New York Law School. He received his Bachelor of Laws in 1924 and earned admission to the bar in 1925.[8]

Between 1925 and 1927, Harlan served as Assistant United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, heading the district's Prohibition unit.[8] He prosecuted Harry M. Daugherty, former United States Attorney General.[5] In 1928, he was appointed Special Assistant Attorney General of New York, in which capacity he investigated a scandal involving sewer construction in Queens. He prosecuted Maurice E. Connolly, the Queens borough president, for his involvement in the affair.[2] In 1930, Harlan returned to his old law firm, becoming a partner one year later. At the firm, he served as chief assistant for senior partner Emory Buckner and followed him into public service when Buckner was appointed United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York. As one of "Buckner's Boy Scouts", eager young Assistant United States Attorneys, Harlan worked on Prohibition cases, and swore off drinking except when the prosecutors visited the Harlan family fishing camp in Quebec, where Prohibition did not apply.[9] Harlan remained in public service until 1930, and then returned to his firm. Buckner had also returned to the firm,[9] and after Buckner's death, Harlan became the leading trial lawyer at the firm.[5]

As a trial lawyer Harlan was involved in a number of famous cases. One such case was the conflict over the estate left after the death in 1931 of Ella Wendel, who had no heirs and left almost all her wealth, estimated at $30–100 million, to churches and charities. However, a number of claimants, most of them imposters, filed suits in state and federal courts seeking part of her fortune. Harlan acted as the main defender of her estate and will as well as the chief negotiator. Eventually a settlement among lawful claimants was reached in 1933.[10] In the following years Harlan specialized in corporate law dealing with the cases like Randall v. Bailey,[11] concerning the interpretation of state law governing distribution of corporate dividends.[12] In 1940, he represented the New York Board of Higher Education unsuccessfully in the Bertrand Russell case in its efforts to retain Bertrand Russell on the faculty of the City College of New York; Russell was declared "morally unfit" to teach.[7] The future justice also represented boxer Gene Tunney in a breach of contract suit brought by a would-be fight manager, a matter settled out of court.[9][12]

In 1937, Harlan was one of five founders of a eugenics advocacy group called the Pioneer Fund, which had been formed to introduce Nazi ideas on eugenics to the United States. He had likely been invited into the group due to his expertise in non-profit organizations. Harlan served on the Pioneer Fund's board until 1954. He did not play a significant role in the fund.[13][14]

During World War II, Harlan volunteered for military duty, serving as a colonel in the United States Army Air Force from 1943 to 1945. He was the chief of the Operational Analysis Section of the Eighth Air Force in England.[5] He won the Legion of Merit from the United States, and the Croix de Guerre from both France and Belgium.[5] In 1946 Harlan returned to private law practice representing Du Pont family members against a federal antitrust lawsuit. In 1951, however, he returned to public service, serving as Chief Counsel to the New York State Crime Commission, where he investigated the relationship between organized crime and the state government as well as illegal gambling activities in New York and other areas.[5][7] During this period Harlan also served as a committee chairman of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, and to which he was later elected vice president. Harlan's main specialization at that time was corporate and antitrust law.[5]

Personal life

In 1928, Harlan married Ethel Andrews, who was the daughter of Yale history professor Charles McLean Andrews.[6] This was the second marriage for her. Ethel was originally married to New York architect Henry K. Murphy, who was twenty years her elder. After Ethel divorced Murphy in 1927, her brother John invited her to a Christmas party at Root, Clark, Buckner & Howland,[15] where she was introduced to John Harlan. They saw each other regularly afterwards and married on November 10, 1928, in Farmington, Connecticut.[6]

Harlan, a Presbyterian, maintained a New York City apartment, a summer home in Weston, Connecticut, and a fishing camp in Murray Bay, Quebec,[12] a lifestyle he described as "awfully tame and correct".[9] The justice played golf, favored tweeds, and wore a gold watch which had belonged to the first Justice Harlan.[9] In addition to carrying his grandfather's watch, when he joined the Supreme Court he used the same furniture which had furnished his grandfather's chambers.[9]

John and Ethel Harlan had one daughter, Evangeline Dillingham (born on February 2, 1932).[6] She was married to Frank Dillingham of West Redding, Connecticut, until his death, and had five children.[5][16] One of Eve's children, Amelia Newcomb, is the international news editor at The Christian Science Monitor[17] and has two children: Harlan, named after John Marshall Harlan II, and Matthew Trevithick.[18] Another daughter, Kate Dillingham, is a professional cellist and published author.

Second Circuit service

Harlan was nominated by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on January 13, 1954, to a seat on the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit vacated by Judge Augustus Noble Hand. Harlan knew this court well, as he had often appeared before it and was friendly with many of the judges.[9] He was confirmed by the United States Senate on February 9, 1954, and received his commission on the next day. His service terminated on March 27, 1955, due to his elevation to the Supreme Court.[19]

Supreme Court service

Harlan was nominated by President Eisenhower on January 10, 1955, as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, to succeed Robert H. Jackson.[2] On being nominated, the reticent Harlan called reporters into his chambers in New York, and stated, in full, "I am very deeply honored."[20] He was confirmed by the Senate on March 16, 1955, by a 71-11 vote,[21] and was sworn into office on March 28, 1955.[22] Despite the brevity of his stay on the Second Circuit, Harlan would serve as the Circuit Justice responsible for the Second Circuit throughout his Supreme Court capacity, and, in that capacity, enjoyed attending the Circuit's annual conference, bringing his wife and catching up on the latest gossip.[9] Additionally, he served as Circuit Justice for the Ninth Circuit from June 25 to June 26, 1963. He assumed retired status on September 23, 1971, serving in that capacity until his death on December 29, 1971.[19]

Harlan's nomination came shortly after the Supreme Court handed down its landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education,[23] declaring segregation in public schools unconstitutional. James Eastland (the chairman of the United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary) and several other southern senators delayed his confirmation, because they (correctly) believed that he would support desegregation of the schools and civil rights.[24] Unlike almost all previous Supreme Court nominees, Harlan appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee to answer questions relating to his judicial views. Every Supreme Court nominee since Harlan has been questioned by the Judiciary Committee before confirmation.[25] The Senate finally confirmed him on March 17, 1955, by a vote of 71–11.[26] He took his seat on March 28, 1955.[5] Of the eleven senators who voted against his appointment, nine were from the South. He was replaced on the Second Circuit by Joseph Edward Lumbard.[27]

On the Supreme Court, Harlan often voted alongside Justice Felix Frankfurter,[4] who was his principal mentor on the court.[15] Some legal scholars even viewed him as "Frankfurter without mustard", though others recognize his own important contributions to the evolution of legal thought.[4] Harlan was an ideological adversary—but close personal friend—of Justice Hugo Black,[28] with whom he disagreed on a variety of issues, including the applicability of the Bill of Rights to the states, the Due Process Clause, and the Equal Protection Clause.[3]

Justice Harlan was very close to the law clerks whom he hired, and continued to take an interest in them after they left his chambers to continue their legal careers. The justice would advise them on their careers, hold annual reunions, and place pictures of their children on his chambers' walls. He would say to them of the Warren Court, "We must consider this only temporary," that the Court had gone astray, but would soon right itself.[9]

Justice Harlan is remembered by people who worked with him for his tolerance and civility. He treated his fellow Justices, clerks and attorneys representing parties with respect and consideration. While Justice Harlan often strongly objected to certain conclusions and arguments, he never criticized other justices or anybody else personally, and never said any disparaging words about someone's motivations and capacity.[29] Harlan was reluctant to show emotion, and was never heard to complain about anything.[9] Harlan was one of the intellectual leaders of the Warren Court. Harvard Constitutional law expert Paul Freund said of him:

His thinking threw light in a very introspective way on the entire process of the judicial function. His decisions, beyond just the vote they represented, were sufficiently philosophical to be of enduring interest. He decided the case before him with that respect for its particulars, its special features, that marks alike the honest artist and the just judge.[30]

Jurisprudence

Harlan's jurisprudence is often characterized as conservative. He held precedent to be of great importance, adhering to the principle of stare decisis more closely than many of his Supreme Court colleagues.[4] Unlike Justice Black, he eschewed strict textualism. While he believed that the original intention of the Framers should play an important part in constitutional adjudication, he also held that broad phrases like "liberty" in the Due Process Clause could be given an evolving interpretation.[31]

Harlan believed that most problems should be solved by the political process, and that the judiciary should play only a limited role.[3] In his dissent to Reynolds v. Sims,[32] he wrote:

These decisions give support to a current mistaken view of the Constitution and the constitutional function of this court. This view, in short, is that every major social ill in this country can find its cure in some constitutional principle and that this court should take the lead in promoting reform when other branches of government fail to act. The Constitution is not a panacea for every blot upon the public welfare nor should this court, ordained as a judicial body, be thought of as a general haven of reform movements.[32]

However, Harlan was not a social conservative.[33] He wrote the plurality opinion in Manual Enterprises, Inc. v. Day, ruling that photographs of nude men are not obscene, one of the first major victories for the early gay rights movement.[34] Despite Harlan’s conservatism, he opposed the Vietnam War and along with Justices William O. Douglas, Potter Stewart and William J. Brennan Jr. unsuccessfully pushed for the Court to hear challenges to its legality.[35]

Equal Protection Clause

The Supreme Court decided several important equal protection cases during the first years of Harlan's career. In these cases, Harlan regularly voted in favor of civil rights—similar to his grandfather, the only dissenting justice in the infamous Plessy v. Ferguson case.[36]

He voted with the majority in Cooper v. Aaron,[37] compelling defiant officials in Arkansas to desegregate public schools. He joined the opinion in Gomillion v. Lightfoot,[38] which declared that states could not redraw political boundaries in order to reduce the voting power of African-Americans. Moreover, he joined the unanimous decision in Loving v. Virginia,[39] which struck down state laws that banned interracial marriage.

Due Process Clause

Justice Harlan advocated a broad interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause. He subscribed to the doctrine that the clause not only provided procedural guarantees, but also protected a wide range of fundamental rights, including those that were not specifically mentioned in the text of the Constitution.[40] (See substantive due process.) However, as Justice Byron White noted in his dissenting opinion in Moore v. East Cleveland, "no one was more sensitive than Mr. Justice Harlan to any suggestion that his approach to the Due Process Clause would lead to judges 'roaming at large in the constitutional field'."[41] Under Harlan's approach, judges would be limited in the Due Process area by "respect for the teachings of history, solid recognition of the basic values that underlie our society, and wise appreciation of the great roles that the doctrines of federalism and separation of powers have played in establishing and preserving American freedoms".[42]

Harlan set forth his interpretation in an often cited dissenting opinion to Poe v. Ullman,[43] which involved a challenge to a Connecticut law banning the use of contraceptives. The Supreme Court dismissed the case on technical grounds, holding that the case was not ripe for adjudication. Justice Harlan dissented from the dismissal, suggesting that the Court should have considered the merits of the case. Thereafter, he indicated his support for a broad view of the due process clause's reference to "liberty". He wrote, "This 'liberty' is not a series of isolated points pricked out in terms of the taking of property; the freedom of speech, press, and religion; the right to keep and bear arms; the freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures; and so on. It is a rational continuum which, broadly speaking, includes a freedom from all substantial arbitrary impositions and purposeless restraints."[43] He suggested that the due process clause encompassed a right to privacy, and concluded that a prohibition on contraception violated this right.[44]

The same law was challenged again in Griswold v. Connecticut.[42] This time, the Supreme Court agreed to consider the case, and concluded that the law violated the Constitution. However, the decision was based not on the due process clause, but on the argument that a right to privacy was found in the "penumbras" of other provisions of the Bill of Rights. Justice Harlan concurred in the result, but criticized the Court for relying on the Bill of Rights in reaching its decision. "The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment stands," he wrote, "on its own bottom."[42] The Supreme Court would later adopt Harlan's approach, relying on the due process clause rather than the penumbras of the Bill of Rights in right to privacy cases such as Roe v. Wade[45] and Lawrence v. Texas.[46]

Harlan's interpretation of the Due Process Clause attracted the criticism of Justice Black, who rejected the idea that the Clause included a "substantive" component, considering this interpretation unjustifiably broad and historically unsound, one of the few issues in which Black was more conservative than Harlan. The Supreme Court has agreed with Harlan, and has continued to apply the doctrine of substantive due process in a wide variety of cases.[3]

Incorporation

Justice Harlan was strongly opposed to the theory that the Fourteenth Amendment "incorporated" the Bill of Rights—that is, made the provisions of the Bill of Rights applicable to the states.[47] His opinion on the matter was opposite to that of his grandfather, who supported the full incorporation of the Bill of Rights.[48] When it was originally ratified, the Bill of Rights was binding only upon the federal government, as the Supreme Court ruled in the 1833 case Barron v. Baltimore.[49] Some jurists argued that the Fourteenth Amendment made the entirety of the Bill of Rights binding upon the states as well. Harlan, however, rejected this doctrine, which he called "historically unfounded" in his Griswold concurrence.[42]

Instead, Justice Harlan believed that the Fourteenth Amendment's due process clause only protected "fundamental" rights. Thus, if a guarantee of the Bill of Rights was "fundamental" or "implicit in the concept of ordered liberty," Harlan agreed that it applied to the states as well as the federal government.[4] Thus, for example, Harlan believed that the First Amendment's free speech clause applied to the states,[50] but that the Fifth Amendment's self-incrimination clause did not.[4]

Harlan's approach was largely similar to that of Justices Benjamin Cardozo and Felix Frankfurter.[4] It drew criticism from Justice Black, a proponent of the total incorporation theory.[1] Black claimed that the process of identifying some rights as more "fundamental" than others was largely arbitrary, and depended on each Justice's personal opinions.[28]

The Supreme Court has eventually adopted some elements of Harlan's approach, holding that only some Bill of Rights guarantees were applicable against the states—the doctrine known as selective incorporation. However, under Chief Justice Earl Warren during the 1960s, an increasing number of rights were deemed sufficiently fundamental for incorporation (Harlan regularly dissented from these rulings). Hence, the majority of provisions from the Bill of Rights have been extended to the states; the exceptions are the Third Amendment, the grand jury clause of the Fifth Amendment, the Seventh Amendment, the Ninth Amendment, and the Tenth Amendment. Thus, although the Supreme Court has agreed with Harlan's general reasoning, the end result of its jurisprudence is very different from what Harlan advocated.[47]

First Amendment

Justice Harlan supported many of the Warren Court's landmark decisions relating to the separation of church and state. For instance, he voted in favor of the Court's ruling that the states could not use religious tests as qualifications for public office in Torcaso v. Watkins.[51] He joined in Engel v. Vitale,[52] which declared that it was unconstitutional for states to require the recitation of official prayers in public schools. In Epperson v. Arkansas,[53] he similarly voted to strike down an Arkansas law banning the teaching of evolution.

In many cases, Harlan took a fairly broad view of First Amendment rights such as the freedom of speech and of the press, although he thought that the First Amendment applied directly only to the federal government.[50] According to Harlan the freedom of speech was among the "fundamental principles of liberty and justice" and therefore applicable also to states, but less stringently than to the national government. Moreover, Justice Harlan believed that federal laws censoring "obscene" publications violated the free speech clause.[50] Thus, he dissented from Roth v. United States,[54] in which the Supreme Court upheld the validity of a federal obscenity law. At the same time, Harlan did not believe that the Constitution prevented the states from censoring obscenity.[55] He explained in his Roth dissent:

The danger is perhaps not great if the people of one State, through their legislature, decide that Lady Chatterley's Lover goes so far beyond the acceptable standards of candor that it will be deemed offensive and non-sellable, for the State next door is still free to make its own choice. At least we do not have one uniform standard. But the dangers to free thought and expression are truly great if the Federal Government imposes a blanket ban over the Nation on such a book. ... The fact that the people of one State cannot read some of the works of D. H. Lawrence seems to me, if not wise or desirable, at least acceptable. But that no person in the United States should be allowed to do so seems to me to be intolerable, and violative of both the letter and spirit of the First Amendment.[54]

Harlan concurred in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan,[56] which required public officials suing newspapers for libel to prove that the publisher had acted with "actual malice." This stringent standard made it much more difficult for public officials to win libel cases. He did not, however, go as far as Justices Hugo Black and William O. Douglas, who suggested that all libel laws were unconstitutional. In Street v. New York,[57] Harlan wrote the opinion of the court, ruling that the government could not punish an individual for insulting the American flag. In 1969 he noted that the Supreme Court had consistently "rejected all manner of prior restraint on publication."[58]

When Harlan was a Circuit Judge in 1955,[59] he authorized the decision upholding the conviction of leaders of the Communist Party USA (including Elizabeth Gurley Flynn) under the Smith Act. The ruling was based on the previous Supreme Court's decisions, by which the Court of Appeals was bound. Later, when he was a Supreme Court justice, Harlan, however, wrote an opinion overturning the conviction of Communist Party activists as unconstitutional in the case of Yates v. United States.[60] Another such case was Watkins v. United States.[61]

Harlan penned the majority opinion in Cohen v. California,[62] holding that wearing a jacket emblazoned with the words "Fuck the Draft" was speech protected by the First Amendment. His opinion was later described by constitutional law expert Professor Yale Kamisar as one of the greatest ever written on freedom of expression.[9] In the Cohen opinion, Harlan famously wrote "one man's vulgarity is another's lyric," a quote that was later denounced by Robert Bork as "moral relativism".[63]

Justice Harlan is credited for establishing that the First Amendment protects the freedom of association.[50] In NAACP v. Alabama,[64] Justice Harlan delivered the opinion of the court, invalidating an Alabama law that required the NAACP to disclose membership lists.[50] However he did not believe that individuals were entitled to exercise their First Amendment rights wherever they pleased. He joined in Adderley v. Florida,[65] which controversially upheld a trespassing conviction for protesters who demonstrated on government property. He dissented from Brown v. Louisiana,[66] in which the Court held that protesters were entitled to engage in a sit-in at a public library. Likewise, he disagreed with Tinker v. Des Moines,[67] in which the Supreme Court ruled that students had the right to wear armbands (as a form of protest) in public schools.

Criminal procedure

During the 1960s the Warren Court made a series of rulings expanding the rights of criminal defendants. In some instances, Justice Harlan concurred in the result,[68] while in many other cases he found himself in dissent. Harlan was usually joined by the other moderate members of the Court: Justices Potter Stewart, Tom Clark, and Byron White.[4]

Most notably, Harlan dissented from Supreme Court rulings restricting interrogation techniques used by law enforcement officers. For example, he dissented from the Court's holding in Escobedo v. Illinois,[69] that the police could not refuse to honor a suspect's request to consult with his lawyer during an interrogation. Harlan called the rule "ill-conceived" and suggested that it "unjustifiably fetters perfectly legitimate methods of criminal law enforcement." He disagreed with Miranda v. Arizona,[70] which required law enforcement officials to warn a suspect of his rights before questioning him (see Miranda warning). He closed his dissenting opinion with a quotation from his predecessor, Justice Robert H. Jackson: "This Court is forever adding new stories to the temples of constitutional law, and the temples have a way of collapsing when one story too many is added."[70]

In Gideon v. Wainwright,[68] Justice Harlan agreed that the Constitution required states to provide attorneys for defendants who could not afford their own counsel. However, he believed that this requirement applied only at trial, and not on appeal; thus, he dissented from Douglas v. California.[71]

Harlan wrote the majority opinion in Leary v. United States—a case that declared the Marijuana Tax Act unconstitutional based on the Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination.[72]

Justice Harlan's concurrence in Katz v. United States[73] set forth the test for determining whether government conduct constituted a search. In this case the Supreme Court held that eavesdropping on the petitioner's telephone conversation constituted a search in the meaning of the Fourth Amendment and thus required a warrant.[4] According to Justice Harlan, there is a two-part requirement for a search: (1) that the individual have a subjective expectation of privacy; and (2) that the individual's expectation of privacy is "one that society is prepared to recognize as 'reasonable.'"[73]

Voting rights

Justice Harlan rejected the theory that the Constitution enshrined the so-called "one man, one vote" principle, or the principle that legislative districts must be roughly equal in population.[74] In this regard, he shared the views of Justice Felix Frankfurter, who in Colegrove v. Green[75] admonished the courts to stay out of the "political thicket" of reapportionment. The Supreme Court, however, disagreed with Harlan in a series of rulings during the 1960s. The first case in this line of rulings was Baker v. Carr.[76] The Court ruled that the courts had jurisdiction over malapportionment issues and therefore were entitled to review the validity of district boundaries. Harlan, however, dissented, on the grounds that the plaintiffs failed to demonstrate that malapportionment violated their individual rights.[76]

Then, in Wesberry v. Sanders,[77] the Supreme Court, relying on the Constitution's requirement that the United States House of Representatives be elected "by the People of the several States," ruled that congressional districts in any particular state must be approximately equal in population. Harlan vigorously dissented, writing, "I had not expected to witness the day when the Supreme Court of the United States would render a decision which casts grave doubt on the constitutionality of the composition of the House of Representatives. It is not an exaggeration to say that such is the effect of today's decision."[77] He proceeded to argue that the Court's decision was inconsistent with both the history and text of the Constitution; moreover, he claimed that only Congress, not the judiciary, had the power to require congressional districts with equal populations.[74]

Harlan was the sole dissenter in Reynolds v. Sims,[32] in which the Court relied on the Equal Protection Clause to extend the one man, one vote principle to state legislative districts. He analyzed the language and history of the Fourteenth Amendment, and concluded that the Equal Protection Clause was never intended to encompass voting rights. Because the Fifteenth Amendment would have been superfluous if the Fourteenth Amendment (the basis of the reapportionment decisions) had conferred a general right to vote, he claimed that the Constitution did not require states to adhere to the one man, one vote principle, and that the Court was merely imposing its own political theories on the nation. He suggested, in addition, that the problem of malapportionment was one that should be solved by the political process, and not by litigation. He wrote:

This Court, limited in function in accordance with that premise, does not serve its high purpose when it exceeds its authority, even to satisfy justified impatience with the slow workings of the political process. For when, in the name of constitutional interpretation, the Court adds something to the Constitution that was deliberately excluded from it, the Court, in reality, substitutes its view of what should be so for the amending process.[32]

For similar reasons, Harlan dissented from Carrington v. Rash,[78] in which the Court held that voter qualifications were subject to scrutiny under the equal protection clause. He claimed in his dissent, "the Court totally ignores, as it did in last Term's reapportionment cases ... all the history of the Fourteenth Amendment and the course of judicial decisions which together plainly show that the Equal Protection Clause was not intended to touch state electoral matters."[78] Similarly, Justice Harlan disagreed with the Court's ruling in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections,[79] invalidating the use of the poll tax as a qualification to vote.

Retirement and death

John M. Harlan's health began to deteriorate towards the end of his career. His eyesight began to fail during the late 1960s.[80] To cover this, he would bring materials to within an inch of his eyes, and have clerks and his wife read to him (once when the Court took an obscenity case, a chagrined Harlan had his wife read him Lady Chatterley's Lover).[20] Gravely ill, he retired from the Supreme Court on September 23, 1971.[5]

Harlan died from spinal cancer[30] three months later, on December 29, 1971.[2] He was buried at the Emmanuel Church Cemetery in Weston, Connecticut.[81][82] President Richard Nixon considered nominating Mildred Lillie, a California appeals court judge, to fill the vacant seat; Lillie would have been the first female nominee to the Supreme Court. However, Nixon decided against Lillie's nomination after the American Bar Association found Lillie to be unqualified.[83] Thereafter, Nixon nominated William Rehnquist (a future Chief Justice), who was confirmed by the Senate.[80]

Despite his many dissents, Harlan has been described as one of the most influential Supreme Court justices of the twentieth century.[84] He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1960.[85] Harlan's extensive professional and Supreme Court papers (343 cubic feet) were donated to Princeton University, where they are housed at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library and open to research.[86] Other papers repose at several other libraries. Ethel Harlan, his wife, outlived him by only a few months and died on June 12, 1972.[87] She suffered from Alzheimer's disease for the last seven years of her life.[15]

See also

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 9)

- List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Warren Court

- List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Burger Court

- Clay v. United States (1971)

- Muhammad Ali's Greatest Fight (2013 television film)

Notes

- Yarbrough, 1992, pp. 10–11

- "John Marshall Harlan Papers". Princeton University Library. Archived from the original on June 22, 2007. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- Yarbrough, 1989, Chapter 3, The bill of rights and the states

- Vasicko, 1980

- Dorsen, 2002, pp. 139–143

- Yarbrough, 1992, pp. 33–35, 41.

- Leitch 1978, pp. ?

- Yarbrough, 1992, pp. 13–16

- Oeslner, Lesley (December 30, 1971). "Harlan dies at 72; on Court 16 years". The New York Times. Retrieved April 17, 2009. (subscription required)

- Yarbrough, 1992, pp. 41–51

- 288 N.Y. 280, 43 N.E.2d 43 (1942)

- Yarbrough, 1992, pp. 52–53

- Tucker, 2002, pp. 6, 51–53

- Lombardo, Paul A. (2002). ""The American Breed": Nazi Eugenics and the Origins of the Pioneer Fund". Albany Law Review. 65 (3): 743–830. PMID 11998853. SSRN 313820.

- Lamb, Brian (1992). "Interview with Tinsley Yarbrough, the author of John Marshall Harlan: Great Dissenter of the Warren Court". National Cable Satellite Corporation. Archived from the original on November 15, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2011.

- "Maud Dillingham, Cesar Becerra Jr". New York Times. July 13, 1997. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- "Amelia Newcomb, Christian Science Monitor", International Reporting Project, archived from the original on April 2, 2016

- Matt Trevithick Archived March 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Boston University Terrier Athletics.

- "Harlan, John Marshall - Federal Judicial Center". www.fjc.gov. Archived from the original on November 5, 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- Rosenbaum, David E. (September 24, 1971). "A lawyer's judge; John Marshall Harlan". The New York Times. Retrieved April 17, 2009. (subscription required)

- McMillion, Barry J. (January 28, 2022). Supreme Court Nominations, 1789 to 2020: Actions by the Senate, the Judiciary Committee, and the President (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved February 19, 2022.

- "Justices 1789 to Present". Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court of the United States. Retrieved February 19, 2022.

- 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

- Dorsen, 2006

- "United States Senate. Nominations". United States Senate. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- Epstein, 2005

- Ravo, Nick (June 9, 1999). "J. Edward Lumbard Jr., 97, Judge and Prosecutor, Is Dead". The New York Times. New York. Archived from the original on November 8, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- Goldman, Jeremy. "Harlan, John M." Oyez.org. Archived from the original on September 16, 2008. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- Dorsen, 2002, pp. 147, 156, 162.

- Staff writer (June 10, 1972). "The Judges' Judge". Time. Archived from the original on October 22, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- Dripps, 2005, pp. 125–131

- 377 U.S. 533, 589 (1964), Harlan J., dissenting

- Murdoch, Joyce; Price, Deborah (May 9, 2002). Courting Justice: Gay Men and Lesbians v. The Supreme Court. Basic Books. p. 78. ISBN 9780465015146. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- "Manual Enterprises, INC. v. Day". Oyez. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- Schoen, Ronert. "A Strange Silence: Vietnam and the Supreme Courft" (PDF). Texas Tech University. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- 163 U.S. 537, 552 (1896), Harlan J., dissenting

- 358 U.S. 1, 4 (1958)

- 364 U.S. 339 (1960)

- 388 U.S. 1 (1967)

- Wildenthal, 2000, p. 1463

- 431 U.S. 494, 544 (1977), White, B., dissenting

- 381 U.S. 479, 501 (1965), Harlan, J., concurring in the judgment

- 367 U.S. 497, 522 (1961), Harlan, J., dissenting

- Dripps, 2005, p. 144

- 410 U.S. 113 (1972)

- 539 U.S. 558 (2003)

- Cortner, 1985

- Wildenthal, 2000

- 32 U.S. 243 (1833)

- O'Neil, 2001

- 367 U.S. 488 (1961)

- 370 U.S. 421 (1962)

- 393 U.S. 97, 114 (1968), Harlan, J., concurring

- 354 U.S. 476, 496 (1957), Harlan, J., concurring in the result in No. 61, and dissenting in No. 582

- O'Neil, 2001, pp. 63–64

- 376 U.S. 254 (1964)

- 394 U.S. 576 (1969)

- Abrams, 2005, pp. 15–16

- "Banken und Finanzprodukte im Vergleich - BankVergleich.com". BankVergleich.com. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- 354 U.S. 298, 300 (1957)

- 354 U.S. 178 (1957)

- 403 U.S. 15 (1971)

- "Conversations: Robert Bork says, Give me liberty, but don't give me filth". Christianity Today. May 19, 1997. Archived from the original on September 7, 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2009.

- 357 U.S. 449 (1958)

- 385 U.S. 39 (1966)

- 383 U.S. 131, 151 (1966), Mr. Justice Black, with whom Mr. Justice Clark, Mr. Justice Harlan, and Mr. Justice Stewart join dissenting

- 393 U.S. 503, 526 (1969), Harlan, J., dissenting

- 372 U.S. 335, 349 (1963), Harlan, J., concurring

- 378 U.S. 478, 492 (1964), Harlan, J., dissenting

- 384 U.S. 436, 504 (1965), Harlan, J., dissenting

- 372 U.S. 353, 360 (1963), Harlan, J., dissenting

- 395 U.S. 6 (1969)

- 389 U.S. 347 (1967)

- Hickok, 1991, pp. 5–7

- 328 U.S. 549, 556 (1946)

- 369 U.S. 186, 266 (1962), Harlan, J., dissenting

- 376 U.S. 1, 20 (1964), Harlan, J., dissenting

- 380 U.S. 89, 97 (1965), Harlan, J., dissenting

- 383 U.S. 663, 680 (1966)

- Dean, 2001

- "Christensen, George A. (1983) Here Lies the Supreme Court: Gravesites of the Justices, Yearbook". Archived from the original on September 3, 2005. Retrieved November 24, 2013. Supreme Court Historical Society at Internet Archive.

- Christensen, George A. (February 19, 2008). "Here Lies the Supreme Court: Revisited". Journal of Supreme Court History. University of Alabama. 33 (1): 17–41. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5818.2008.00177.x. S2CID 145227968..

- a MetNews staff writer (October 31, 2002). "Justice Lillie Remembered for Hard Work, Long Years of Service". Metropolitan News-Enterprise. Archived from the original on September 6, 2008. Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- Yarbrough, 1992

- "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter H" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2018. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- "John Marshall Harlan Papers, 1884-1972 (mostly 1936-1971) - Finding Aids". findingaids.princeton.edu. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- Staff (June 13, 1972). "Mrs. John Marshall Harlan, 76, Widow of Supreme Court Justice". New York Times. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

References

- Abrams, Floyd (2005). "The Pentagon papers case". Speaking Freely. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-03375-1.

- Cortner, Richard (1985). "The Nationalization of the Bill of Rights: An Overview" (PDF). American Political Science Association and American Historical Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 29, 2020. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- Dean, John (2001). "2". The Rehnquist Choice. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-7432-2607-3.

- Dorsen, Norman; Newcomb, Amela Ames (2002). "John Marshall Harlan II: Remembrances by his Law Clerks". Journal of Supreme Court History. 27 (2): 138–175. doi:10.1111/1540-5818.00040. S2CID 144526140. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013.

- Dorsen, Norman (2006). "The selection of U.S. Supreme Court justices". International Journal of Constitutional Law. 4 (4): 652–663. doi:10.1093/icon/mol028.

- Dripps, Donald A. (2005). "Justice Harlan on Criminal Procedure: Two Cheers for the Legal Process School" (PDF). Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law. 3: 125–168. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 21, 2010. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- Epstein, Lee; Segal, Jeffrey A.; Staudt, Nancy; Lindstädt, Rene (2005). "The role of qualifications in the confirmation of nominees to the U.S. Supreme court" (PDF). Florida State University Law Review. 32: 1145–1174. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2008.

- Goldman, Jeremy. "Harlan, John M." Oyez.org. Archived from the original on September 16, 2008. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- Hickok, Eugene W. Jr. (1991). "Representation By Quota: The Decline of Representative Government in America" (pdf). The Heritage Lectures. Washington, D.C.: The Heritage Foundation. ISSN 0272-1155.

- Leitch, Alexander (1978). A Princeton Companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04654-9. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- Mayer, Martin (1968). Emory Buckner. New York: Harper & Row. (Harlan arranged for Mayer to write this book about his mentor Emory Buckner and wrote the book's Introduction.)

- Oeslner, Lesley (December 30, 1971). "Harlan dies at 72; on Court 16 years". The New York Times. Retrieved April 17, 2009.(subscription required)

- O'Neil, Robert M. (2001). "The neglected first amendment jurisprudence of the second justice Harlan" (PDF). NYU Annual Survey of American Law. 58: 57–66. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2008.

- Tucker, William H. (2002). The Funding of Scientific Racism: Wickliffe Draper and the Pioneer Fund. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-02762-8.

- Vasicko, Sally Jo (1980). "John Marshall Harlan: neglected advocate of federalism" (PDF). Modern Age. 24 (4): 387–395. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 29, 2008. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- Wildenthal, Bryan H. (2000). "The Road to Twining: Reassessing the Disincorporation of the Bill of Rights" (PDF). Ohio State Law Journal. 61: 1457–1496. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 29, 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- Yarbrough, Tinsley E. (1989). Mr. Justice Black and his critics. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-0866-9.

- Yarbrough, Tinsley E. (1992). John Marshall Harlan: Great Dissenter of the Warren Court. Oxford, Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506090-4.

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). Oxford, Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. Oxford, Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Shapiro, David L. (1969). The Evolution of a Judicial Philosophy: Selected Opinions and Papers of Justice John M. Harlan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. p. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

- Woodward, Robert; Armstrong, Scott (1979). The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court. New York: Avon Books. ISBN 978-0-380-52183-8.

External links

- John Marshall Harlan II at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Ariens, Michael. "John Marshall Harlan II". www.michaelariens.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- John M. Harlan Papers at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University

- Harlan, Louis R. "Harlan Family In America: A Brief History". Harlan Family in America. Archived from the original on February 10, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- Fox, John, Capitalism and Conflict, Biographies of the Robes, John Marshall Harlan II. Public Broadcasting Service.

- Supreme Court Historical Society, "John Marshall Harlan II." Archived April 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- Booknotes interview with Tinsley Yarbrough on John Marshall Harlan: Great Dissenter of the Warren Court, April 26, 1992.

- John Marshall Harlan II at Find a Grave