John Allan (colonel)

Colonel John Allan M.P. J.P. (January 3, 1746 – February 7, 1805) was a Canadian politician who became an officer with the Massachusetts Militia in the American Revolutionary War. He served under George Washington during the Revolutionary War as Superintendent of the Eastern Indians and Colonel of Infantry, and he recruited Indian tribes of Eastern Maine to stand with the Americans during the war and participated in border negotiations between Maine, and New Brunswick.[1]

Colonel John Allan | |

|---|---|

| Born | January 3, 1746 Edinburgh Castle, Scotland |

| Died | February 7, 1805 Lubec, Maine |

| Buried | Treat Island |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Machias |

| Memorials | Cenotaph on Treat Island |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Patton (1743 –1819) |

| Relations | Children: William Allan; Mark Allan; John Allan; Isabel Maxwell Allan; George Washington Allan; Horatio Gates Allan; Winckworth Sargent Allan |

| Other work | Superintendent of Eastern Indians |

Early life and education

Allan was born in Edinburgh Castle in Scotland,[2] the son of Major William Allan (military officer) (1720 –1790), 'a Scottish gentleman of means and an officer in the British Army',[1] and his wife Isabella, daughter of Sir Eustace Maxwell.[3] The Allan family temporarily resided in Edinburgh Castle where they had sought refuge during the Jacobite rising of 1745, under the Deputy Governor, General George Preston, Commander-in-Chief of Scotland.

After the end of the War of the Austrian Succession, many British officers including Colonel Allan's father were discharged from service. William Allan was then offered a position in the British colony of Nova Scotia, which had previously been in French possession and he moved there with his family in 1749. William Allan arrived in the City of Halifax, Nova Scotia, in a military capacity, where the family remained for ten years before moving to Fort Lawrence. William Allan served in Nova Scotia during the Seven Years' War, and after the fall of French Canada, and the ceding of the colony to the British in the Treaty of Paris (1763), was granted farmland in the newly ceded territory. This farmland was cared for and worked by French Acadians "who became for a time servants to the conquerors of their own territory". In a few years he was known to be a person of some wealth and prosperity from his holdings.[4]

Given William Allan's background, it is surprising that his son became such an advocate for American independence. Several factors in young John Allan's childhood may have contributed to his patriotic views. John Allan was sent to Massachusetts to receive an education, as were many young sons of wealthy British officers and landowners, because Nova Scotia was still relatively unsettled. He learned as a child both French and some Native American dialects. Both of these language skills would prove crucial for success in his later endeavors. Colonel John Allan's education in Massachusetts was likely a large factor in his support for the American patriots over the British, because at that time, Boston, Massachusetts was arguably the center of patriotic fervor. Another factor is that after the Proclamation of 1763, many New Englanders migrated to areas in Nova Scotia, such as Fort Lawrence, where Colonel John Allan grew up. Patriotic sentiment among his Bostonian neighbors in Nova Scotia could have influenced his political leanings. Also, Nova Scotia was geographically close to New England, which was the center of patriotic resistance. It was also dependent on New England for many supplies and ammunition. Regular contact with New Englanders imbued with patriotic fervor could have caused Allan to differ so strongly from his father's views. Colonel John Allan eventually became estranged from his father. This estrangement was likely due to an irreconcilable difference of view concerning the Revolutionary War.[5]

Contributions to the Revolutionary War

After his schooling, Colonel John Allan moved back to Halifax and worked in mercantile and agricultural fields. As the son of a rich landowner, he was probably gifted land in Halifax by his father. Allan rose quickly in public service jobs to higher positions. He served in Halifax as justice of the peace, Clerk of the Nova Scotia Supreme Court, and Clerk of the Sessions,[5] as well as representing the Cumberland Township in the Nova Scotia House of Assembly from 1775 to 1776. In 1776 his seat was declared vacant because of non-attendance.[6] His neglect of this position was likely due to the patriotic activities in which he had begun by this time to take part. After the Battle of Lexington and Concord and the Battle of Bunker Hill, Allan began to freely express his patriotic opinions, and, charged for treason to the Crown, he fled across the border to the town of Machias, Maine, in which anti-British sentiment was rampant. He arrived in Machias on August 11, 1776, where he met Jonathan Eddy and unsuccessfully attempted to stop him from attempting to take over the British-held Fort Beauséjour (Fort Cumberland), where Allan's wife and five children lived, with a disproportionately small army of Americans. Despite Allan's efforts, Eddy attempted the takeover of Fort Cumberland, which proved disastrous for the American cause and for any American supporters living in the area.[7]

Travels to Boston and Philadelphia (1776–1777)

Before fleeing Halifax, Allan met with the Mi'kmaq and Maliseet (St. John's) Indian tribes in 1776 in order to secure their support. The British had previously approached them offering gifts and asking that they adopt a position of neutrality. Allan negotiated a treaty with these tribes that was ratified on August 29, 1776, stipulating an agreement that they would support the patriots in a war for independence. However, later that year in September, these same tribes argued that the people who signed the treaty had not been legitimate representatives, and that therefore the tribes would maintain a position of neutrality.[5]

In October 1776, Allan went to Boston and then to Philadelphia on a mission to secure aid for the Indian tribes in Northeastern Maine and Nova Scotia.

In Philadelphia, Allan met with General George Washington. Although the particulars of their meeting are unknown, Washington's knowledge of and concern about Indian support and frontier settlements in Northeastern Maine suggests that Allan discussed these topics with him. However, Washington opposed expeditions into Nova Scotia because of the number of British soldiers there and the limited number of expeditions that the colonists could afford. Perhaps Washington's reluctance was a result of Eddy's ill-fated mission to seize Fort Cumberland, which resulted in a tightening of British forces there and the destruction of patriots' property, such as John Allan's. Allan's wife was also taken by the British to Halifax as a prisoner after Eddy's failed mission and she was interrogated for several months about her husband. Such happenings might have caused Washington to be reluctant about military action in Northeastern Maine and Nova Scotia, and to focus more on strategic relations with Indian tribes.[7]

After meeting with Washington in Philadelphia, Allan went to Baltimore, where he was received by the Continental Congress on January 1, 1777. Congress appointed him as the agent for Indian tribes in Nova Scotia and Northeastern Maine. The Continental Congress outlined his duties as "to engage [the Indians'] friendship and prevent their taking a part on the side of Great Britain". He was to do this through trade and propaganda.[5]

The Battle of Machias (1777)

After leaving for Boston, where he would take headquarters as agent for Indian tribes, Allan primarily worked on acquiring and building up an army to secure Western Nova Scotia for the colonies. Patriotic sentiment throughout Nova Scotia made an attempt at seizure seem plausible. Allan asked Congress for three thousand men as well as supplies and schooners. Allan was so insistent on capturing Fort Cumberland because he recognized it as the base where many of Britain's supplies arrived. He also recognized that it would be difficult for Britain to expend effort on a war in Nova Scotia as well as the war in the thirteen colonies. Other motivations underlying Allan's mission included protecting the frontier and preserving relations with the Indians in Nova Scotia. The result of the attempt on Fort Cumberland was debatable: although Allan claimed that it was successful, he may have exaggerated the number of British soldiers killed and wounded.[4][5]

Contributions as Superintendent of Eastern Indians

Colonel John Allan set out to negotiate with the St. John's Indian tribe on May 29, 1777. He used tactics such as stressing the Indians' importance to the American cause. Allan also employed economic tactics such as raising the price of furs so that the British would refuse to buy Indian furs and Indian sentiment toward the British would turn bitter.[5] Allan faced significant danger during his negotiations with the Indians because the Indians were internally divided and the British were also actively attempting to gain their support. Both the British and British-supporting Indians made several attempts on Allan's life and all of these he escaped, although some were narrow escapes.[4] Eventually, because of the backlash by British troops after Eddy's failed attempt on Fort Cumberland, Allan led Indians who were loyal to America to Machias, Maine in order to protect them.[8]

During the Battle of Machias in August 1777, the Indian tribes that Allan had recruited proved indispensable, despite the little amount of supplies that Congress had afforded them. In a few surviving correspondences by Allan, he pleads Congress for more supplies.[8]

After this battle until the end of the war, Washington determined that there would be no more military expeditions in Nova Scotia. However, Colonel Allan still had a lot of work to do as superintendent of Indians. Congress gave to him the additional responsibility of commanding troops of about three hundred men at Machias, which was still vulnerable to British attack. During his time in Machias, Allan had to face the challenges of shifting Indian alliances, limited aid from Congress, and resistance against his trade restrictions. Allan unsuccessfully asked to be relieved from duty, as he felt that he could not maintain good relationships with the Indians without better aid from Congress. He felt that he could do more good and have greater influence on the Indians who resided a short distance away from Machias. Congress denied his request by reappointing him as Superintendent of Eastern Indians, probably because they could find no other man better suited for the job. Despite his concerns, Allan did manage to keep most of the Indian tribes in Machias from lending their support to the British.[5]

Congress eventually allowed Allan to leave his position as Superintendent of Eastern Indians after the war's end. This was because his services were no longer crucial: the war had been won. The Eastern Indian Department, in which he worked, was dissolved anyway in 1785. After Allan vacated his position, the Indian tribes with whom he had previously worked pled with him to help relieve them from the deplorable post-war conditions they were facing. However, Allan could not do much to help them as he was no longer superintendent. He did, however, work to prevent post-war alliances between the British in Canada and Indian tribes.[5]

Overall, John Allan received compliments from Congress for his work as Superintendent of Eastern Indians. He was consistently promoted and praised in the Eastern Indian Department. Most government officials believed that Allan was indispensable to the cause and possessed unique skill in negotiating with the Indian tribes.[5]

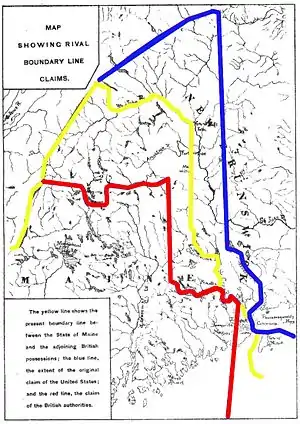

Role in Boundary Negotiations of Eastern Maine

Following the end of the war, Allan stayed active in the patriotic cause even though he no longer officially worked as Superintendent of Eastern Indians. He noticed that there were encroachments by settlers from Nova Scotia into what he believed was United States territory. He wrote to the Continental Congress and the Massachusetts Council about how the border between New Brunswick (which used to be considered part of Nova Scotia) and the United States ought to be different than the British stated. Allan's arguments were used in future boundary negotiations.[5]

Postwar Years/ Legacy

After the end of the war, Allan began an unsuccessful mercantile business on Allan's Island, now called Treat Island, in Passamaquoddy Bay.[10] Records show that Allan traded several times with Benedict Arnold. Because Congress was stripped of money after the war, Allan, like many other officers in the war, suffered poverty and did not receive timely compensation for his work in the war. He had to write to Congress in order to receive pay for his work.[5] Allan died on February 7, 1805, in Lubec, Maine.[11] He was buried on Treat Island and there can be found a cenotaph that was dedicated to him in 1860 and inscribed with the names of his descendants.[12]

Although Colonel John Allan is not a name that many recognize and his contributions to the war were not flashy and militaristic, this man had a profound impact on the outcome of the war. His skills at negotiation prevented the British from securing the support of northeastern Indian tribes, and his careful attention and devotion to the United States even outside of his job influenced the boundary of Maine that still stands today.

Further reading and information

Notes

- John Allan and the Revolution in Eastern Maine

- John Allan's Proposal for an Attack on Nova Scotia 1775-76.Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society, Volume 2, pp. 11-16

- Dictionary of Canadian Biography

- Memoir of Colonel John Allan: an Officer of the Revolution

- Military operations in eastern Maine and Nova Scotia during the revolution (1867)

- Heirlooms Reunited Treat Island (Allan Island)

- Maine Coast Heritage Fund Treat Island

- Maine Memory Network Allan's Cenotaph on Treat Island

- Electric Scotland Mini Biography Colonel John Allan

References

- "Colonel John Allan". www.electricscotland.com. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607-1896. Marquis Who's Who. 1967.

- p. 218

- Memoir of Colonel John Allan [microform] : an officer of the revolution, born in Edinburgh Castle, Scotland, Jan. 3, 1746, died in Lubec, Maine, Feb. 7, 1805, with a genealogy. 1867. ISBN 9780665626463. Retrieved 2016-11-30 – via archive.org.

- "John Allan and the revolution in eastern Maine ". archive.org. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- Elliott, Shirley B. (1984). The Legislative Assembly of Nova Scotia, 1758-1983: a biographical directory (PDF). Halifax: Province of Nova Scotia. p. 248&2. ISBN 0-88871-050-X.

- "Biography – ALLAN, JOHN – Volume V (1801-1820) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- Military operations in eastern Maine and Nova Scotia during the revolution [microform]. 1867. ISBN 9780665078262. Retrieved 2016-11-30 – via archive.org.

- "A fascinating tale... Winfield Scott and the Aroostook War". History is Now Magazine, Podcasts, Blog and Books – Modern International and American history. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- "Treat Island (Allan's Island), Passamaquoddy Bay, Maine; John Allan; Cannon Insignia". www.heirloomsreunited.com. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- Mack, Sharon Kiley; Staff, B. D. N. (29 December 2009). "Heritage trust preserves island off Lubec". The Bangor Daily News. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- "Colonel John Allan's cenotaph, Treat's Island, 1970". Maine Memory Network. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

External links

![]() Media related to John Allan (colonel) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to John Allan (colonel) at Wikimedia Commons