Yogini

A yogini (Sanskrit: योगिनी, IAST: yoginī) is a female master practitioner of tantra and yoga, as well as a formal term of respect for female Hindu or Buddhist spiritual teachers in Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia and Greater Tibet. The term is the feminine Sanskrit word of the masculine yogi, while the term "yogin" IPA: [ˈjoːɡɪn] is used in neutral, masculine or feminine sense.[1]

A yogini, in some contexts, is the sacred feminine force made incarnate, as an aspect of Parvati, and revered in the yogini temples of India as the Sixty-four Yoginis. The names of the yoginis differ between temples.

History

The worship of yoginis began outside Vedic Religion, starting according to Vidya Dehejia with the cults of local village goddesses, the grama devatas. Each one protects her village, sometimes giving specific benefits such as safety from the stings of scorpions. Gradually, through Tantra, these goddesses were grouped together into a number believed powerful, most often 64, and they became accepted as a valid part of Hinduism.[2] Historical evidence on Yogini Kaulas suggests that the practice was well established by the 10th century in both Hindu and Buddhist tantra traditions.[3] The nature of the yoginis differs between the traditions; in Tantra they are fierce and scary, while in India, celibate female sanyassins may describe themselves as yoginis.[4]

Devi

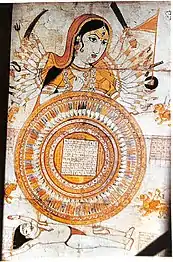

In ancient and medieval texts in Hinduism, a yogini is associated with or directly an aspect of Devi, the goddess.[5] In the 11th century collection of myths, the Kathāsaritsāgara, a yogini is one of a class of females with magical powers, sorceresses sometimes enumerated as 8, 60, 64 or 65.[6] The Hatha Yoga Pradipika mentions yoginis.[7] Devi is sometimes portrayed with a superimposed Yogini Chakra, wheel of the 64 Yoginis, placing them as aspects of Devi.[8]

Cloth painting of Devi with a superimposed Yogini Chakra, wheel of the 64 Yoginis. Rajasthan, 19th century.

Cloth painting of Devi with a superimposed Yogini Chakra, wheel of the 64 Yoginis. Rajasthan, 19th century.

Nath Yoga

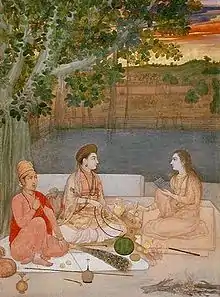

The term yogini has been in use in medieval times for a woman who belongs to the Nath Yoga tradition founded around the 11th century.[9] They usually belong to the Shaiva tradition, but some Natha belong to the Vaishnava tradition.[10] Either way, states David Lorenzen, they practice Yoga and their principal God tends to be Nirguna, that is, without form and semi-monistic,[10] influenced in the medieval era by Advaita Vedanta Hinduism, Madhyamaka Buddhism, and by Tantra.[11][12] Human yoginis were a large part of this tradition, and many 2nd-millennium paintings depict them and their Yoga practices. Lorenzen states that the Nath yogis were popular with the rural population in South Asia, with medieval era tales and stories about Nath yogis continuing to be remembered in contemporary times, in the Deccan, western and northern states of India and in Nepal.[10]

Tantra

Women in Tantra traditions, whether Hindu or Buddhist, are similarly called yoginis.[13][14] In Tantric Buddhism, Miranda Shaw states that many women like Dombiyogini, Sahajayogicinta, Lakshminkara, Mekhala, Kankhala Gangadhara, Siddharajni, and others, were respected yoginis and advanced seekers on the path to enlightenment.[15]

64 Yoginis

Characteristics

From around the 10th century, yoginis appear in groups, often of 64. They appear as goddesses, but human female adepts of tantra can emulate "and even embody" these deities, who can appear as mortal women, creating an ambiguous and blurred boundary between the human and the divine.[16] Yoginis, divine or human, belong to clans; in Shaiva, among the most important are the clans of the 8 Mothers (matris or matrikas). Yoginis are often theriomorphic, having the forms of animals, represented in statuary as female figures with animal heads. Yoginis are associated with "actual shapeshifting" into female animals, and the ability to transform other people.[17] They are linked with the Bhairava, often carrying skulls and other tantric symbols, and practising in cremation grounds and other liminal places. They are powerful and dangerous. They both protect and disseminate esoteric tantric knowledge. They have siddhis, extraordinary powers, including the power of flight;[18] many yoginis have the form of birds or have a bird as their vahana or animal vehicle.[19] In later Tantric Buddhism, dakini, a female spirit able to fly, is often used synonymously with yogini.[20] The scholar Shaman Hatley writes that the archetypal yogini is "the autonomous Sky-traveller (khecari)", and that this power is the "ultimate attainment for the siddhi-seeking practitioner".[21]

Into the late 20th century, yoginis inspired a "deep sense of fear and awe" among "average" people in India, according to the scholar Vidya Dehejia. She notes that such fear may be ancient, as the Brahmanda Purana and the Jnanarnava Tantra both warn that transmitting secret knowledge to non-initiates will incur the curse of the yoginis.[22]

Association with Matrikas

In Sanskrit literature, the yoginis have been represented as the attendants or manifestations of Durga engaged in fighting with the demons Shumbha and Nishumbha, and the principal yoginis are identified with the Matrikas.[23] Other yoginis are described as born from one or more Matrikas. The derivation of 64 yoginis from 8 Matrikas became a tradition. By the mid-11th century, the connection between yoginis and Matrikas had become common lore. The mandala (circle) and chakra of yoginis were used alternatively. The 81 yoginis evolve from a group of 9 Matrikas. The 7 Mothers or Saptamatrika (Brahmi, Maheshvari, Kaumari, Vaishnavi, Varahi, Indrani (Aindri) and Chamundi), joined by Chandi and Mahalakshmi, form the nine-Matrika cluster. Each Matrika is considered to be a yogini and is associate with 8 other yoginis resulting in the troupe of 81 (9 times 9).[24] Some traditions have only 7 Matrikas, and thus fewer yoginis.

Names

There is no universally-agreed list of the names of the 64 yoginis; Dehejia located and compared some 30 different lists, finding that they rarely corresponded, and that there must have been multiple traditions concerning the 64. She states that the lists can be categorised into those that include the Matrikas among the Yoginis and give the Yoginis high status, and those that do neither. The high status means that the Yoginis are either aspects of the Great Goddess Devi, or her acolytes.[25]

The Kalika Purana includes 16 Matrikas among the yoginis. 9 of these Matrikas are of the Brahmi series; Dehejia comments that in this tradition, the yoginis are "64 varying aspects of Devi herself"; they are to be worshipped "individually".[26]

The Agni Purana does not include the Matrikas among the yoginis, but states that they are related. It divides the yoginis into 8 family groups, each one led by a Matrika, who is either the mother or another relative of each of her yoginis. [25]

The Agni Purana, the Skanda Purana and the Kalika Purana each contain two lists (namavalis) of yoginis with often wholly differing contents. The Sri Matottara Tantra tells that the Khechari Chakra and the Yogini Chakra are both circles of 64 yoginis, while the Mula Chakra has a circle of 81 and the Malini Chakra has a circle of 50.[27] The number 8 is auspicious; its square, 64, is "even more potent and efficacious".[28] In tantric texts there are supposedly 64 Agamas and Tantras, 64 Bhairavas, 64 mantras, 64 sites sacred to the Goddess (pithas), and 64 extraordinary powers (siddhis). Dehejia notes that the yoginis are closely associated with the siddhis.[28]

Temples to the 64 yoginis

Yogini temples are simple compared to typical Indian temples, without the usual towers, gateways and elaborate carvings that attract scholarly attention.[22]

Major extant hypaethral (open air) temples of the 64 yoginis (Chausathi Jogan)[29][23] in India built between the 9th and 12th centuries include two in Odisha at Hirapur and Ranipur Jharial;[30] and three in Madhya Pradesh, at Khajuraho, Bhedaghat,[31][32] and the well-preserved hilltop temple at Mataoli in Morena district.[33][34]

The iconographies of the yogini statues in the various temples are not uniform, nor are the yoginis the same in each set of 64. In the Hirapur temple, all the yoginis are depicted with their Vahanas (animal vehicles) and in standing posture. In the Ranipur-Jharial temple the yogini images are in dancing posture. In the Bhedaghat temple, the yoginis are seated in lalitasana.[29]

Chausathi Yogini Temple, Hirapur, Odisha, 2012. The yoginis have recently been venerated with the gift of headscarves.

Chausathi Yogini Temple, Hirapur, Odisha, 2012. The yoginis have recently been venerated with the gift of headscarves. One of the Yoginis of Chausathi Yogini Temple at Hirapur, Odisha. There is an offering of flowers at the yogini's feet.

One of the Yoginis of Chausathi Yogini Temple at Hirapur, Odisha. There is an offering of flowers at the yogini's feet..jpg.webp) 8th-century Chausath Yogini Temple, Morena, Madhya Pradesh

8th-century Chausath Yogini Temple, Morena, Madhya Pradesh

Statues

Temple images of yoginis have been made in materials including stone and bronze from at least the 9th century.

Siddhis

The goal of yogini worship, as described in both Puranas and Tantras, was the acquisition of siddhis.[35]

The Sri Matottara Tantra describes 8 major powers, as named in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, namely: Anima, becoming microscopically small, giving knowledge of how the world works; Mahima, becoming huge, able to view the whole solar system and universe; Laghima, becoming weightless, allowing levitation and astral travel away from the body; Garima, becoming very heavy and powerful; Prakamya, having an irresistible willpower, able to control the minds of others; Ishitva, controlling both body and mind and all living things; Vashitva, controlling the natural elements, such as rain, drought, volcanoes, and earthquakes; and Kamavashayita, gaining all one's desires and any treasure.[36]

The Sri Matottara Tantra lists many other more or less magical powers that devotees can obtain by invoking the yoginis correctly, from the ability to cause death, disillusion, paralysis, or unconsciousness to provocation, delightful poetry, and seduction.[37]

Practices

Wine, flesh, blood

Yogini worship, intended to yield occult powers, consisted of a set of rituals called Mahayaga. These took place in the sacred space of the circular temple, appropriate for the working of magic. The yoginis were invoked with offerings of wine, flesh, and blood. The Sri Matottara Tantra describes the yoginis delighting in and drunk upon wine; one of them is indeed named Surapriya (lover of wine). The Kularnava Tantra provides a recipe for brewing the yoginis' drink, involving dry ginger, lemon bark, black pepper, blossoms, honey and jaggery sugar in water, brewed for 12 days. The yoginis danced and drank blood and wine, according to the Brhaddharma Purana. The Kaulavali Nirnaya adds that blood and meat are needed to worship the yoginis. The sacrifice of animals, always male, is practised at Assam's Kamakhya Temple, where the 64 yoginis continue to be worshipped.[38]

Corpse rituals

Sculptures at some of the yogini temples such as Shahdol, Bheraghat and Ranipur-Jharial depict the yoginis with kartari knives, human corpses, severed heads, and skull-cups. There appear to have been corpse rituals, shava sadhana, as is described in the Vira Tantra, which calls for offerings of food and wine to the 64 yoginis, and for pranayama to be practised while sitting on a corpse. The Vira Cudamani requires the naked practitioner (the sadhaka) and his partner to sit on the corpse and practise maithuna, tantric sex. The Sri Matottara Tantra instructs that the corpse must be intact, beautiful, and fresh; Dehejia notes that this does not imply human sacrifice, but the selection of the best corpses. In the circle of the Mothers, in front of the statue of Bhairava, the corpse is to be bathed, covered in sandalwood paste, and have its head cut off in a single stroke. The Mothers will, it states, be watching this from the sky, and the sadhaka will acquire the 8 major siddhis. Further, flesh from the corpse is eaten; Dehejia states that the practice "is not uncommon" and that in Kamakhya, people avoid leaving a corpse overnight before cremation "for fear of losing it to tantric practitioners".[39]

Maithuna

Dehejia notes that none of the yogini temples have sculptures depicting maithuna, ritual sex, nor are there any small figures in embrace carved into the pedestal of any yogini statue. All the same, she writes, it is "fairly certain" that maithuna was one of the Mahayaga rituals.[40] The Kularnava Tantra mentions "the eight and the sixty-four mithunas" (couples in embrace); and it proposes that the 64 yoginis should be portrayed "in embrace with the 64 Bhairavas" and that the resulting images should be worshipped.[40] The Jnanarnava Tantra describes the 8 Matrikas paired off (yugma yugma) with the 8 Bhairavas.[40]

The Yogini Chakra, also called the Kaula Chakra or Bhairavi Chakra, is formed as a circle (Chakra) of at least 8 people, with equal numbers of men and women. Dehejia writes that this meant that pairing was random rather than having people arriving in couples, and that this explained the careful sexual preparations in Kaula texts, such as anointing the body and touching its parts to stimulate both partners. Caste was ignored during such Chakra-puja (circle worship), all men being Shiva while in the circle, and all women being Devi, and the women of the lowest castes were thought the best suited to the role.[40]

Dehejia notes, too, that the need for "privacy and secrecy" given such practices readily explained the isolated hilltop locations of the yogini temples, well away from towns with "orthodox Brahmanical thinking favouring vegetarianism and objecting to alcohol", let alone having maithuna among the temple rituals.[40]

David Gordon White writes that the modern practice of '"Tantric sex"' (his quotation marks) is radically different from the medieval practice.[41]

See also

- Apsara – Type of female spirit of the clouds and waters in Hindu and Buddhist culture

- Devadasi – Woman dedicated to the worship of a temple's patron god

- Vajrayogini – Tantric Buddhist female Buddha and ḍākiṇī

- Women in Hinduism – Position of women in the religious texts of Hinduism

- Yakshini – Class of nature spirits in Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain religious mythologies

- Yoga for women – Yoga as exercise for and marketed to women

References

- Monier-Williams, Monier. "योगिन् (yogin)". Monier-Williams Sanskrit Dictionary 1899 List. Sanskrit English Dictionary with Etymology. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- Dehejia 1986, pp. 1–10.

- White 2012, p. 73-75, 132-141.

- Dunn 2019.

- Dehejia 1986, pp. 19–31.

- Monier-Williams, Sanskrit Dictionary (1899).

- Feuerstein 2000, p. 350.

- Dehejia 1986, p. 22.

- White 2012, p. 8-9, 234-256, 454-467.

- Lorenzen & Muñoz 2012, pp. x–xi.

- Lorenzen 2004, pp. 310–311.

- Lorenzen & Muñoz 2012, pp. 24–25.

- Gross 1993, pp. 87, 85–88.

- White 2013, pp. xiii–xv.

- Shaw 1994.

- Hatley 2007, pp. 12–13.

- Hatley 2007, pp. 13–14.

- Hatley 2007, pp. 16–17.

- Hatley 2007, p. 14.

- Hatley 2007, p. 59.

- Hatley 2007, p. 17.

- Dehejia 1986, pp. ix–x.

- Bhattacharyya 1996, p. 128.

- Wangu 2003, p. 114.

- Dehejia 1986, p. 187.

- Dehejia 1986, p. 188.

- Dehejia 1986, p. xi.

- Dehejia 1986, p. 44.

- Chaudhury, Janmejay. Origin of Tantricism and Sixty-four Yogini Cult in Orissa in Orissa Review, October 2004 Archived 25 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Patel, C.B. Monumental Efflorescence of Ranipur-Jharial in Orissa Review, August 2004, pp.41-44 Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Jabalpur district official website – about us Archived August 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Chausath Yogini Temple – Site Plan, Photos and Inventory of Goddesses Archived April 17, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "Ekattarso Mahadeva Temple". Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Dehejia 1986, pp. 91–144.

- Dehejia 1986, pp. 53–66.

- Dehejia 1986, pp. 53–54.

- Dehejia 1986, p. 54.

- Dehejia 1986, pp. 56–58.

- Dehejia 1986, pp. 58–61.

- Dehejia 1986, pp. 62–64.

- White 2006, p. xiii.

Sources

- Bhattacharyya, Narendra Nath (1996) [1974]. History of the Sakta Religion (2nd ed.). Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. ISBN 978-8121507134.

- Dehejia, Vidya (1986). Yogini Cult and Temples: A Tantric Tradition. National Museum, Janpath, New Delhi.

- Dunn, Laura M. (2019). "Yoginīs in the Flesh: Power, Praxis, and the Embodied Feminine Divine". Journal of Dharma Studies. Springer. 1 (2): 287–302. doi:10.1007/s42240-019-00023-4. ISSN 2522-0926. S2CID 151147589.

- Feuerstein, Georg (2000). The Shambhala Encyclopedia of Yoga. Shambhala Publications.

- Gross, Rita (1993). Buddhism After Patriarchy. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0791414033.

- Hatley, Shaman (2007). The Brahmayāmalatantra and Early Śaiva Cult of Yoginīs. University of Pennsylvania (PhD Thesis, UMI Number: 3292099). pp. 1–459.

- Lorenzen, David (2004). Religious Movements in South Asia, 600-1800. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195664485.

- Lorenzen, David N.; Muñoz, Adrián (2012). Yogi Heroes and Poets: Histories and Legends of the Naths. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-1438438900.

- Shaw, Miranda (1994). Passionate Enlightenment: Women in Tantric Buddhism. Princeton University Press.

- Wangu, Madhu Bazaz (2003). Images of Indian Goddesses. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-8170174165.

- White, David Gordon (2012). The Alchemical Body: Siddha Traditions in Medieval India. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226149349.

- White, David Gordon (2013). Tantra in Practice. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120817784.

- White, David Gordon (2006) [2003]. Kiss of the Yogini: 'Tantric Sex' in its South Asian Contexts. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226894843.

_LACMA_M.2011.156.4_(1_of_2).jpg.webp)