James Lee Clark

James Lee Clark (May 13, 1968 – April 11, 2007) was an American murderer with an intellectual disability whose controversial execution by the state of Texas sparked international outcry. The controversy involved the argument[1][2][3][4][5] that his execution violated the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Atkins v. Virginia (2002),[6] which held that executions of intellectually disabled criminals is cruel and unusual punishment, which is prohibited by the Eighth Amendment.

James Lee Clark | |

|---|---|

| Born | May 13, 1968 Caddo Parish, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | April 11, 2007 (aged 38) Huntsville Unit, Huntsville, Texas, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Execution by lethal injection |

| Occupation | Plumber's helper |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Conviction(s) | Capital murder |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Details | |

| Victims | Jesus Garza, 16 Shari Catherine Crew, 17 |

| Date | June 7, 1993 |

| Location(s) | Denton County, Texas |

| Weapons | Shotgun |

Clark and his accomplice, James Richard Brown, were charged with capital murder for the June 7, 1993 killing of 16-year-old Jesus Garza, and the robbery, rape and murder of 17-year-old Shari Catherine "Cari" Crews in Denton County, Texas. However, Clark was never tried for the Garza murder,[7][8] and Brown was found guilty of only the robbery charge, for which he was sentenced to 20 years.[9]

Early life

Clark was born in Caddo Parish, Louisiana. Court documents revealed that his father disappeared the day he found out Clark's mother was pregnant. Testimony from a psychologist at his appeals hearing stated that Clark told him he had his first drink when he was seven years old and was commonly drunk by the age of 13, at which point he also began to smoke cannabis regularly. After failing two grades and being placed in special education classes he dropped out of school in the ninth grade.[9]

At the age of 15 he was remanded into the Gainesville State School, a reformatory for boys and girls in Gainesville, Texas, for auto theft.[8] At that time his mother told the Texas Youth Commission that he "has no friends in school ... because he steals from them all." Clark was subsequently diagnosed as having a "conduct disorder, associated with psychological deprivation, coupled with features of immature personality."[10] At the Gainesville State School, Clark was able to complete his GED and was released at the age of 18 to find his mother had abandoned him, wanting nothing more to do with him.[8]

Criminal history

In 1989 Clark was convicted of a felony – the burglary of a building – and incarcerated in state prison. In 1991 he pleaded guilty to theft by a check and was confined to the county jail for 20 days, fined, and ordered to pay restitution. In 1992 he was convicted of burglary and received a 10-year sentence in prison, which is where he met Brown. On May 26, 1993, after serving only ten months of his sentence, Clark was granted parole due to the problem of overcrowding in the Texas prison system. Two weeks later Clark and Brown were arrested for the Crews and Garza murders.[11]

Murder of Catherine Crews and Jesus Garza

On June 4, 1993, Clark and Brown participated in breaking into vehicles, stole a shotgun and a rifle,[12] and went in search of someone to rob. In the early morning hours of June 7, 1993, they came upon Crews and Garza at Clear Creek near Denton, Texas, and the following day their bodies were pulled from the water.[8] Crews' body was discovered nude with a pair of shorts around her neck and her wrists bound with her own bra. She had been raped and had died from a shotgun wound to the back of her head.[11] Garza had been also killed by a close-range shotgun blast originating below his chin. Also recovered from the creek were a .22 rifle with the stock sawed off and the murder weapon, a 12-gauge shotgun.[13]

That same morning, paramedics and police officers responded to a call of a gunshot victim at a local service station. Upon arrival they found Brown with a serious shotgun wound to the leg, attended by Clark, who claimed they had been attacked by a robber who shot Brown while they were fishing at Three Rivers Bridge. However, no evidence was found at that scene to support the claim of the crime, or that anyone had been present on the location or fishing at that time. Both suspects were covered with white sand consistent with the banks of Clear Creek. Confronted with this evidence, Brown led police to Garza's body.[14] Subsequent investigation discovered that Brown had actually shot himself at point-blank range in the act of assaulting the teens.[12]

Due to Clark and Brown's conflicting statements, a search warrant was obtained to search the trailer Clark and Brown shared, in violation of their paroles,[15][16] located in Aubrey, Texas. There police discovered the stock to the sawed-off rifle, which was a match to the rifle found in the creek, as well as ammunition and evidence that, days prior to the murder, Clark and Brown had purchased ammunition for the murder weapon.

DNA evidence provided by Clark matched evidence taken from Crews' body, proving that Clark had sexually assaulted her. Additionally, blood determined to be that of Brown, Crews and Garza was found splattered on Clark's shoes.[11][12][13]

Both men were arrested at the Aubrey trailer after moderate resistance. They ultimately admitted they had been at Clear Creek, first claiming they witnessed Garza shoot Crews, before eventually admitting they had indeed robbed the teens. Each blamed the other for the actual murders.[8] Clark claimed that it was Brown who instigated the crime and shot himself using the rifle as a bludgeon on Garza, after which he killed both teens. Brown countered that it was Clark who committed the murders.[12] On September 12, 2000, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals would find in favor of Brown's version of the story, on the grounds that with Brown's injury occurring prior to the murders, Clark must have unloaded the spent cartridge and reloaded the shotgun.[12]

Conviction and appeals

On April 29, 1994, a jury in Denton County convicted James Lee Clark of robbery and the murder and rape of Crews. On May 3, 1994, Judge Sam Houston sentenced Clark to death.[8]

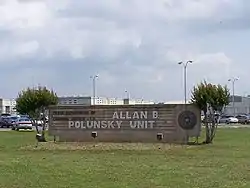

Clark was initially located in the Ellis Unit, but was transferred to the Allan B. Polunsky Unit (formerly the Terrell Unit) in 1999.[17] Clark filed an appeal asserting he had been denied effective assistance of counsel because his original trial attorneys, Richard Podgorski and Henry Paine, made no opening arguments, called no witnesses for guilt or innocence in either the trial or penalty phase, and did not perform adequate discovery, having made no attempt to contact or interview any members of Clark's family or other relevant persons from his past.[10] In fact, there is no evidence they even pursued these avenues despite the Supreme Court ruling, Wiggins v. Smith (2003), that established standards for effective legal counsel, stating that counsel must perform a reasonable exploration of investigation in constituting defense strategy or risk creating an unconstitutional deprivation of rights to effective counsel.

Brown's trial for the murder of Garza was delayed due to the injury of his leg, and at his trial he was depicted as appearing "young and defenseless as he sat at the defense table in a wheelchair".[7] Brown admitted to the robbery, but denied involvement in the murders, describing how he was shot in the act of trying to prevent the crime, and expressed remorse for his acts.[9] Ultimately, he was convicted of only the robberies, was sentenced to 20 years, and has since been denied for parole twice.[8]

On October 6, 1996, the court upheld James Lee Clark's conviction and sentence on direct appeal. On October 15, 1996, his trial attorneys informed Clark they would no longer represent him and were replaced by James Rasmussen.[13] On April 19, 1997, Clark filed a writ of habeas corpus with the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals challenging the validity of his conviction and sentence and asserting eleven grounds for relief, including his claim of ineffectual counsel. The courts denied his application on July 8, 1998, without ever holding an evidentiary hearing, choosing instead to simply review the court records.[10]

On July 27, 1998, Clark appealed this decision to the United States district court; the appeal was denied on December 13, 1999, again without allowing discovery or an evidentiary hearing. On January 12, 2000, he requested the district court review this decision, which was denied on January 28, 2000, including his petition to reexamine his claim of mental retardation being a mitigating circumstance to the crimes.[10]

After the landmark Supreme Court decision in Atkins v. Virginia (2002), which outlawed the execution of persons deemed mentally retarded, Clark moved his sentence should be commuted to life imprisonment without possibility of parole.[9]

The Supreme Court did not specifically outline exact definitions for "mental retardation" and suggested states follow the definition used by the American Association on Mental Retardation (which generally stated that an IQ less than 70 with two or more supporting limitations be used as the guideline), leaving ultimate decision to the individual states. The State of Texas adopted two definitions, both of which contain the same three basic elements, that mental retardation was a disability characterized by "significantly subaverage" intellectual functioning, accompanied with "related limitations in adaptive functioning" and a documented onset of these characterizations prior to the age of 18. Further, they determined that in testing for retardation "scores gathered through intelligence testing are necessarily imprecise and must be interpreted flexibly."[1] The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals ruled that Clark did not meet any of the three criteria for retardation, and affirmed the lower court ruling to uphold his conviction and sentence.[10] An execution date was set for November 21, 2002. However, on November 18, 2002, the execution was stayed pending further examination of Clark's assertion of being mentally retarded, pursuant to the Atkins ruling.[14]

In April 2003 Clark was assessed by clinical psychologist Dr. George C. Denkowski, who had previously assessed four other post-Atkins cases and concluded only one of the four had clear mental retardation under the statutes. Denkowski performed a six-hour examination of Clark, administering the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III (WAIS-III) and the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (ABAS). He determined that Clark had an IQ of 65 and had adaptive skills deficits in the areas of health, safety, social and work, thus clearly falling under the restrictions set by the Atkins ruling.

Despite the fact that the Harris County Prosecutor cited Denkowski's expertise in upholding his findings in the other four cases, Denton County District Attorney Bruce Isaacks rejected the findings, fired Denkowski and hired Dr. Thomas Allen to assess the possibility that Clark was faking mental retardation.[18]

After interviewing Clark for two hours and 16 minutes, during which Allen did not perform any standardized tests to determine Clark's IQ, Allen determined that Clark was indeed faking his retardation by intentionally presenting himself as less intelligent to avoid execution. He cited the fact that Clark's prison cell contained copies of newspaper articles, crossword puzzles and a copy of the Charles Dickens book A Tale of Two Cities. It was ultimately revealed that none of the puzzles had been completed, the articles were about the Atkins case and had been sent to him from people outside the prison as gifts. Clark had stated that he had never read the book.[19]

The defense then hired their own doctor to do an assessment of Clark, choosing Dr. Denis Keyes, whose expert studies had been cited in the actual Atkins ruling. Keyes examined Clark over two sessions lasting a total of seven and a half hours, administering the Kaufman Adolescent and Adult Intelligence Test and the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale, and found that Clark had an IQ of 68.[18] Keyes stated that he felt Clark's ability to behave appropriately for his age was "virtually nonexistent" and concluded that Clark should not be executed, citing both the Texas Mentally Retarded Persons Act and the Atkins ruling.[20] Keyes stated, "Individuals with mental retardation typically have severe deficits in judgment potential, and are simply unable to understand the consequences of their behaviors. People with mental retardation have several characteristics; among these are defective intellectual capacity, shorter attention spans, poor memory, poor planning ability, lack of ability to appreciate the consequences of their actions, severe learning problems, marked deficits in adaptive skill areas, and limited ability to learn from previous experience. James's background confirms problems with virtually every one of the above characteristics."[20] Additionally, Keyes noted his support of Dendowski's findings, calling them "credible and correct" and his opinion that Allen's assessment did not meet the legally required guidelines for diagnosis and ruling out a diagnosis, based on his failure to perform accepted standardized testing. Both Denkowski and Keyes rejected Allen's diagnosis and agreed that Clark was not faking his mental retardation.[1]

On November 17, 2003, a hearing, presided over by Judge Lee Gabriel, was held to examine this evidence. Gabriel, over defense objections, ruled that Clark would appear in court handcuffed, shackled, and wearing an electroshock stun belt,[1][21] On November 20, after a three-day hearing, Gabriel rejected the findings of both Keyes and Denkowski and accepted those of Allen,[1][18] ruling that Clark did not meet the legal standards for mental retardation. She cited a 1983 IQ test administered at the Gainesville State School indicating Clark's IQ at 74, stating that as it was given to Clark as a youth it was a more reliable standard as he had "no reason to fake results at that point." Dr. Jim Flynn, an expert on changes in IQ scores over time (the Flynn effect) wrote that "the best estimate" of Clark's IQ in 2003 would be 68.57 (similar to what Keyes determined), and "it is almost certain that [Clark's IQ] is not 70 or above."[1]

In further support of her ruling, Gabriel allowed and gave weight to testimony from untrained lay people whose statements were of anecdotal nature and unreliable. One such witness was Clark's former landlord, who readily admitted she had memory problems, who testified that she believed that Clark's ability to pay his own bills, barter chores for rent reduction and capacity to play card games similar to Uno, meant he could not be retarded.[10][18] This was in direct conflict with the Texas Persons With Mental Retardation Act which dictates, "'Person with mental retardation' means a person determined by a physician or psychologist licensed in this state or certified by the department to have subaverage general intellectual functioning with deficits in adaptive behavior.' That is, only a licensed physician or psychologist may determine who's mentally retarded. Anecdotal information, or the opinions of untrained laypeople is not meaningful."[22] None-the-less, Judge Gabriel declared Clark fit for execution.[8]

On January 20, 2005, the district court rendered final judgment denying the successive habeas corpus petition, which was overturned on March 16, 2005, when the district court granted Clark's application for a certificate of appealability. However, on July 20, 2006, the 5th Circuit Court affirmed the judgment January 2005 ruling and denied habeas relief. On August 29, 2006, the court denied Clark's petition for rehearing. Finally, on February 26, 2007, the Supreme Court denied Clark's petition for writ of certiorari. The trial court reset his execution date for April 11, 2007[14] and on February 28, 2007, Judge Gabriel signed the execution order.

Execution

The case drew international attention and campaigns to stop the execution were waged by Amnesty International,[1] Amnesty USA,[2] Petitions Online, Urgent Action Network,[3] Texas Moratorium Network[4] and other anti-death penalty groups.[5]

On April 11, 2007, the day of the execution, the Steinway piano that John Lennon used to compose the 1971 song "Imagine" was placed outside the front door of the prison as a protest to the execution, a sign of peace and statement that there is too much violence in the world.[23]

That same day, Texas Governor Rick Perry refused to commute the death sentence.[8] Two hours prior to the execution, the Supreme Court denied a last-minute appeal,[24] and at 6:17 p.m., James Lee Clark was executed in the Walls Unit of Huntsville Prison by means of lethal injection.[5][25] He requested no final meal. When asked if he had any final words he gave a nervous chuckle and stated, "Uh, I don't know. Um, I don't know what to say. I don't know …" He then seemed to notice the witnesses in the gallery and added, "I didn't know anybody was there," he laughed again and said, "Howdy." The lethal cocktail of medications were administered, and Clark made a gurgling sound and became still.[9]

See also

References

- "USA (Texas): Death penalty / Legal concern: James Lee Clark (M)". 5 April 2007. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- "www.floridasupport.us • View topic - James Lee Clark - executed". Archived from the original on 2009-09-03. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- "Texas Moratorium Network: Person with Low IQ about to Become 152nd Rick Perry Execution". Stopexecutions.blogspot.com. 2007-04-11. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- "Man called mentally retarded executed in Texas". Turkishpress.com. 2007-04-12. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- "DARYL RENARD ATKINS, PETITIONER v. VIRGINIA". June 20, 2002. Retrieved August 6, 2006.

- "DPOA - News Detail". Archived from the original on 2009-09-03. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- "Killer to reap what he sowed | Denton Record-Chronicle | News for Denton County, Texas | Local News". Archived from the original on 2008-07-04. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- "James Lee Clark #1070". Clarkprosecutor.org. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- "NCADP - the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty". Archived from the original on 2009-05-16. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- "Texas Attorney General News Release - Media Advisory: James Clark scheduled for execution". Archived from the original on 2009-09-03. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- "US 5th Circuit Opinions and Cases | FindLaw". Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- "Offender Information - James Clark". Archived from the original on 2009-01-07. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- "Media Advisory: James Clark scheduled for execution". Oag.state.tx.us. Archived from the original on 2012-07-17. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- "Killer of Denton high school girl executed | Houston & Texas News | Chron.com - Houston Chronicle". Archived from the original on 2011-05-22. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- "Convicted killer of Denton student executed | Dallas Morning News | News for Dallas, Texas | Latest News". Archived from the original on 2008-07-09. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- "Death Row Facts." Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Retrieved on February 4, 2016.

- "April 11, 2007 - Texas Set of Execute Mentally Retarded Man". Archived from the original on 2007-03-31. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Possibly Mentally Retarded Man to be Executed in Texas, Where Almost All 2007 Executions Have Occurred | Death Penalty Information Center". Deathpenaltyinfo.org. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- "Lethal Injection: USA (Texas) James Lee Clark (m), white, aged 38". Lethal-injection-florida.blogspot.com. 2007-04-05. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- "Texas Health & Safety Code - Section 591.003. Definitions - Texas Attorney Resources - Texas Laws". Archived from the original on 2009-09-04. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- Velsey, Kim. "The New York Times - Breaking News, World News & Multimedia". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- Velsey, Kim. "The New York Times - Breaking News, World News & Multimedia". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2017-06-16.

- "Texas executes man for murder, rape of teen". Reuters. April 12, 2007.