James Henry Carmichael Jr.

James Henry Carmichael Jr. "Slim" (April 2, 1907 – December 1, 1983) was a pioneering aviator, crop duster, barnstormer, airmail pilot, airline pilot, airline president, Special Assistant to the Federal Aviation Administration(FAA), and one of only ten recipients of the Airmail Flyers' Medal of Honor.

James Henry Carmichael Jr. | |

|---|---|

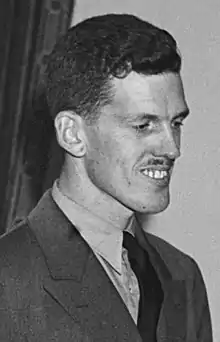

Cropped image of Carmichael waiting to receive Airmail Flyers' Medal of Honor from FDR. | |

| Born | April 2, 1907 Newark, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | December 1, 1983 Delray Beach, Florida, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | "Slim" |

| Occupation | Aviator |

| Spouse | Jessie I Northrop |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Airmail Flyers' Medal of Honor (1933) Horatio Alger Award (1958) |

| Signature | |

| |

Born on April 2, 1907, in Newark, New Jersey Carmichael was the second of three children born to James Henry Carmichael and Ida Coe Miner. James H. Carmichael Jr. died of cancer at his home on December 1, 1983, in Delray Beach, Florida.

Career

Carmichael worked as a miner, a clerk and a farmer before learning to fly in 1926 at the age of 19. After six hours of flying lessons, he became a flight instructor himself. Some of his first flight jobs consisted of crop-dusting, barnstorming and stunt flying before settling in as an Airmail pilot and mechanic for Central Airlines. He received his Limited Commercial Pilot rating, no. 3490, in 1928.[1][2]

He married Jessie Northrop, of the famous aviation family, on July 4, 1930.

He went to work for Pittsburgh Airways in 1931 for a short time and then Newark Air Service from 1931 to 1934. In 1934 he was a hired by Central Airlines as a mechanic and the company's first pilot.

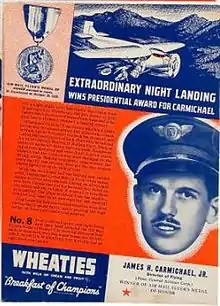

In 1935 he was recommended by the President of the Air Line Pilots Association, Dave Behncke, and was awarded the Airmail Flyers Medal of Honor for safely landing an aircraft with six passengers after an engine fell off, smashing one landing wheel and damaging a second engine over Hancock, Maryland. Carmichael, nicknamed "Slim" due to his tall slender build, became one of only 10 pilots to receive the medal and was number 8 in a series of 8 box covers on the popular breakfast cereal Wheaties.[3]

On November 16, not more than two weeks after receiving his medal, he was taking off from the Allegheny County Airport and made it less than 100 feet above the runway when the engines on the Stinson Model A (NO-15108) Tri-motor began to sputter and then stop completely. He and co-pilot Edward Gerber along with lone passenger Tracey Baker, of Chicago, were all ok after he made a quick belling landing. The plane slid some 300 feet at 100 mph across the landing field, over a 30-foot embankment and into thick underbrush before coming to a stop. The following investigation determined water in the fuel as the cause of the engine failure.[4]

In 1936 Carmichael moved from Chief Pilot to Operations Manager after Pennsylvania Airlines and Central Airlines merged becoming Pennsylvania Central Airlines (PCA).

By 1939 Slim was the Director of Operations and went to Santa Monica, California, to pilot the first of PCA's new fleet of DC-3s from Douglas Aircraft factory to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. [5]

December 18, 1945, he was elected vice president in charge of operations for PCA. He headed the Technical Industrial Intelligence Committee (TIIC) that studied German military and commercial aviation (APO 413). The TIIC was created as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff on September 14, 1945, but transferred to the Department of Commerce in January 1946. The TIIC was the search group mechanism, composed of 380 civilians representing seventeen American Industries with direct links to major American manufacturing concerns.

The worst air disaster for Capital Airways during his career occurred on the evening of June 13, 1947. The following day Carmichael was one of the first to arrive on site of the crash along with Red Cross Official Gordon O Stone, and Capital's Maintenance Director James Franklin. Franklin had spotted the crash site from a small search plane. The three had to abandon their jeep and hike 3 miles to the crash site due to the rain soaked ground. The wreckage covered more than 100 yards of the forest and would require a bulldozer to clear a path for recovery vehicles. The DC-4, a converted Army C-54, which went missing the night before, had flow at full speed and level flight strait into the side of the mountain just 200 feet below the summit. It was the third major airline crash in 15 days. With this being the third crash of a former Army C-54 the military grounded all remaining C-54s pending an investigation.

He eventually rose to Executive Vice President of the Airlines and in 1947 he was named president. He remained the president when PCA became Capital Airlines. During his time as president of the company the airline was in financial trouble. He introduced the "Nighthawk" service providing fairs on evening flights at a reduced rate to compete with the railroad ticket prices. This became the nation's first coach fair and boosted nighttime flying during a time the planes would have been sitting in the hangars. With the new coach fair's catching on flying was no longer just for the well to do. With his innovative thinking and aggressive cost cutting style Carmichael was able to reduce the company's $10 million debt and posted a profit of $1.5 million by 1950 and Capital became the 5th largest airline in the booming industry. [6]

In 1954 Carmichael, as president of Capital Airlines, announced the purchase of Viscount turboprop airplanes, introducing the turbo-jet airliner by the British Vickers-Armstrong Company to American commercial air travel and providing the first jet powered airlines in the nation. This provided more long term stability and growth for the Airline. He tried to consolidate with other airlines but was unsuccessful. [7]

In 1957 Lansing Michigan, Capital Airlines Michigan base, voiced its frustration over poor service and years of promised improvement. That same year Capital realized its highest profits ever with an increase in passengers and cargo and a decrease in Airmail. Carmichael was president of Capital Airlines from 1947 to 1957 and chairman until 1958 when he resigned amide conflicts over a proposed merger with United Airlines. Capital would eventually merge into United Airlines in 1961.

On May 8, 1958, he received the Horatio Alger Award, from the American Schools and Colleges Association for his exceptional rise to prominence in business and industry. The presentation took place in New York City along with seven other awardees.[8]

After leaving Capital Airlines he joined the Fairchild Engine and Airplane Corporation in September 1958. In December he was made Executive Vice President and then President in 1959. He held a unique position in the aviation community as the only airplane manufacture to have ever served as an airline President, that being with Capitol Airlines from 1947 to 1957. At this time Fairchild was producing the Fairchild F-27, a jet-prop airliner designed for the smaller "Feeder" airlines. During his time as President Carmichael and Fairchild employees worked with the community including blood drives for the American Red Cross as well as honoring Boy Scouts at the annual Eagle Scouts Award dinner. With lower than expected orders of the F-27, continued layoffs,[9] and heavy losses there was a shake up in the leadership. In October 1960 he resigned and was replaced by founder, and board chairman, Sherman M Fairchild.[10][11][12]

He joined the Riddle Airlines, later Airlift International, board of directors in August 1962 and was made chairman in September. He had previously been a consultant for Riddle.[13]

He retired in 1978 after several years of running J. H. Carmichael Associates, a Washington lobbying firm, and serving as a special assistant in the Federal Aviation Administration.[14][15]

The flight incident

On a night flight over Maryland's mountains from Washington, D.C., to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the left motor of Slim Carmichael's tri-motored plane shook loose and, dropping like a plummet, and smashed a landing wheel! What a spot to be in! Treacherous inky black peaks below and the closest airport 100 miles away – back in Washington! A moment to check the situation, and Carmichael swiftly turned back. Hurriedly he radioed for an emergency landing at Bolling Field. Then, as suddenly as the left motor had torn loose, the remaining motors sputtered and went dead! A quick check showed that the controls also were damaged by the falling motor. Making emergency repairs while the plane rapidly lost altitude, Slim got the two motors started again just in the nick of time. With one motor and half the landing gear carried away, Carmichael circled Bolling Field, while rescue squads scurried into position. Calling on all his skill as a flyer, Carmichael put his battered ship down on one wheel and the tail-skid. A moment of breathless anticipation! The plane wobbled from the impact steadied and came to an awkward but safe landing! Cool-headed action in a ticklish situation won Slim Carmichael's medal fairly, again proving the high caliber of America's commercial aviators. (Wheaties box #8)[16]

Medal from the President

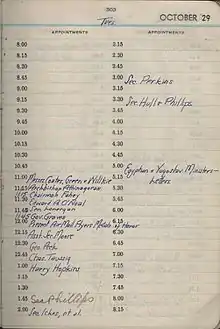

29 October 1935 at a ceremony (12:00 - 12:15) in the White House Carmichael was one of seven aviators awarded the Airmail Flyers’ Medal of Honor by president Franklin Delano Roosevelt for extraordinary achievement. All seven of the pilots saved the mail in hazardous landings.

Present at the ceremony were: President, Franklin Delano Roosevelt; Postmaster General, James A Farley; Lewis S Turner of Fort Worth, Texas; James H Carmichael Jr. of Detroit, Michigan; Edward A Bellande of Los Angeles, California; Gordon S Darnell of Kansas City, Missouri; Willington P McFail of Murfreesboro, Tennessee; Roy H Warner of Portland, Oregon; And Grover Tyler of Seattle, Washington. Bellande's deed was chronicled on the well known Wheaties cereal box cover as part of a series of 8 box covers regarding the feats of pilot's awarded the Air Mail Flyers Medal of Honor.

Medal citation

For extraordinary achievement while piloting air mail plane No. 408H on April 21, 1933, during a night flight from Washington, D.C., to Detroit, Michigan. At an altitude of 3200 feet and about half way to Pittsburgh, Pa., with no warning whatsoever the left outboard engine of the tri-motored plane crashed from the ship. Carmichael adjusted the controls to return the plane to a level position and turned back to Washington. In breaking from the ship the left engine had pulled the outboard heater control open and affected the center engine altitude adjustment. The center engine cut out until the altitude control was discovered and readjusted. Realizing that he had about 100 miles to fly in returning to Washington, the pilot climbed to an altitude of 4500 feet in order not to overheat the remaining two engines on the plane. A survey of the damage was made from the cockpit window with the aid of a flashlight, from which it was determined that the landing gear had been damaged. The pilot, therefore, decided that a landing should be made at Bolling Field, which is larger than the Washington Airport, and would be more advantageous for the one-wheel type of landing which would have to be made with damaged landing gear. He also desired to avail himself of the trained Army personnel and their emergency equipment, including ambulances and firetrucks. The pilot made all arrangements for landing by radio communication and received the fullest cooperation from the Bolling Field authorities. A one-wheel landing was made with little additional damage to the ship and no injury to passengers and mail.[17]

References

- "Pilot License". Directory of Licensed Pilots. Department of Commerce Aeronautics Bulletin No. 20. July 31, 1928.

- "Pilot License Supplement". Supplement to Directory of Licensed Pilots. Supplement 2 to Aeronautics Bulletin No. 20. November 1, 1926.

- M. A., Roddy (July 1935). "Highlights 1935". Popular Aviation. XVII (1): 64. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- "Belly Landing". Vol. 52, no. 146. Press Publishing Company. The Pittsburgh Press. November 16, 1935.

- Lloyd, Kristin (1996). "Flying The Capitol Way". Historic Alexandria Quarterly. 2 (7): 3.

- Beyer, Morten S. (October 23, 2009). Flying Higher, a true story. Victoria, BC, Canada: Trafford Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 9781425166533. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- "Civil Aviation, 1954" (PDF). Flight Globe. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- "Horatio Alger Award". No. 31. Wilmington Morning News. May 9, 1958.

- "President is replaced at Fairchild Engine". No. Sec 2, Page 28. The Courier-Journal, Louisville, KY. October 6, 1960.

- "New plane for "Feeder" lines". No. 12. Monroe Morning News. July 4, 1959.

- "Scouts Honored". No. Page 7. The Daily Mail, Hagerstown, MD. February 14, 1959.

- "Donations of Blood". No. Page 5. The Daily Mail, Hagerstown, MD. March 31, 1959.

- "Riddle Selects New Executives". No. 12. The Palm Beach Post. October 1, 1962.

- Murphy, Joan. "NASM "Wall of Honor"". Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. NASM. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- R. A. "Ray", Lemmon (April 6, 2015). Not Flying Alone: An autobiography. 1663 Liberty Drive, Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4969-7420-4. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - McCarty, Philip R (January 1966). "The Airmail Flyer's Medal of Honor". The Airpost Journal. 67 (1): 9–18.

- Medal, Presentation. "FDR presenting Airmail Flyers Medal of Honor". Library of Congress. Harris & Ewing collection. Retrieved April 11, 2016.