Isolobal principle

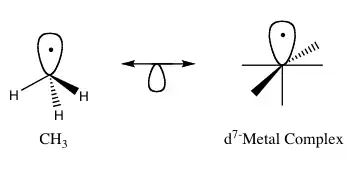

In organometallic chemistry, the isolobal principle (more formally known as the isolobal analogy) is a strategy used to relate the structure of organic and inorganic molecular fragments in order to predict bonding properties of organometallic compounds.[1] Roald Hoffmann described molecular fragments as isolobal "if the number, symmetry properties, approximate energy and shape of the frontier orbitals and the number of electrons in them are similar – not identical, but similar."[2] One can predict the bonding and reactivity of a lesser-known species from that of a better-known species if the two molecular fragments have similar frontier orbitals, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). Isolobal compounds are analogues to isoelectronic compounds that share the same number of valence electrons and structure. A graphic representation of isolobal structures, with the isolobal pairs connected through a double-headed arrow with half an orbital below, is found in Figure 1.

For his work on the isolobal analogy, Hoffmann was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1981, which he shared with Kenichi Fukui.[3] In his Nobel Prize lecture, Hoffmann stressed that the isolobal analogy is a useful, yet simple, model and thus is bound to fail in certain instances.[1]

Construction of isolobal fragments

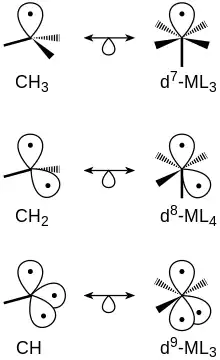

To begin to generate an isolobal fragment, the molecule needs to follow certain criteria.[4] Molecules based around main group elements should satisfy the octet rule when all bonding and nonbonding molecular orbitals (MOs) are filled and all antibonding MOs are empty. For example, methane is a simple molecule from which to form a main group fragment. The removal of a hydrogen atom from methane generates a methyl radical. The molecule retains its molecular geometry as the frontier orbital points in the direction of the missing hydrogen atom. Further removal of hydrogen results in the formation of a second frontier orbital. This process can be repeated until only one bond remains to the molecule's central atom.

The isolobal fragments of octahedral complexes, such as type ML6, can be created in a similar fashion. Transition metal complexes should initially satisfy the eighteen electron rule, have no net charge, and their ligands should be two electron donors (Lewis bases). Consequently, the metal center for the ML6 starting point must be d6. Removal of a ligand is analogous to the removal of hydrogen of methane in the previous example resulting in a frontier orbital, which points toward the removed ligand. Cleaving the bond between the metal center and one ligand results in a ML−

5 radical complex. In order to satisfy the zero-charge criteria the metal center must be changed. For example, a MoL6 complex is d6 and neutral. However, removing a ligand to form the first frontier orbital would result in a MoL−

5 complex because Mo has obtained an additional electron making it d7. To remedy this, Mo can be exchanged for Mn, which would form a neutral d7 complex in this case, as shown in Figure 3. This trend can continue until only one ligand is left coordinated to the metal center.

Relationship between tetrahedral and octahedral fragments

Isolobal fragments of tetrahedral and octahedral molecules can be related. Structures with the same number of frontier orbitals are isolobal to one another. For example, the methane with two hydrogen atoms removed, CH2 is isolobal to a d7 ML4 complex formed from an octahedral starting complex (Figure 4).

MO theory dependence

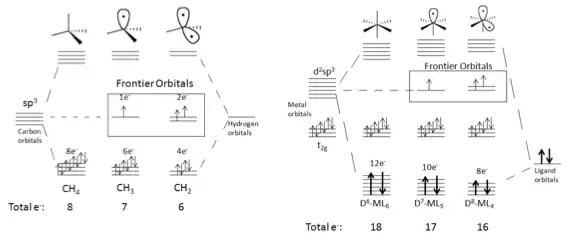

Any sort of saturated molecule can be the starting point for generating isolobal fragments.[5][6] The molecule's bonding and nonbonding molecular orbitals (MOs) should be filled and the antibonding MOs empty. With each consecutive generation of an isolobal fragment, electrons are removed from the bonding orbitals and a frontier orbital is created. The frontier orbitals are at a higher energy level than the bonding and nonbonding MOs. Each frontier orbital contains one electron. For example, consider Figure 5, which shows the production of frontier orbitals in tetrahedral and octahedral molecules.

As seen above, when a fragment is formed from CH4, one of the sp3 hybrid orbitals involved in bonding becomes a nonbonding singly occupied frontier orbital. The frontier orbital’s increased energy level is also shown in the figure. Similarly when starting with a metal complex such as d6-ML6, the d2sp3 hybrid orbitals are affected. Furthermore, the t2g nonbonding metal orbitals are unaltered.

Extensions of the analogy

The isolobal analogy has applications beyond simple octahedral complexes. It can be used with a variety of ligands, charged species and non-octahedral complexes.[7]

Isoelectronic fragments

The isolobal analogy can also be used with isoelectronic fragments having the same coordination number, which allows charged species to be considered. For example, Re(CO)5 is isolobal with CH3 and therefore, [Ru(CO)5]+ and [Mo(CO)5]− are also isolobal with CH3. Any 17-electron metal complex would be isolobal in this example.

In a similar sense, the addition or removal of electrons from two isolobal fragments results in two new isolobal fragments. Since Re(CO)5 is isolobal with CH3, [Re(CO)5]+ is isolobal with CH+

3.[8]

Non-octahedral complexes

| Octahedral MLn |

Square-planar MLn−2 |

|---|---|

| d6: Mo(CO)5 | d8: [PdCl3]− |

| d8: Os(CO)4 | d10: Ni(PR3)2 |

The analogy applies to other shapes besides tetrahedral and octahedral geometries. The derivations used in octahedral geometry are valid for most other geometries. The exception is square-planar because square-planar complexes typically abide by the 16-electron rule. Assuming ligands act as two-electron donors the metal center in square-planar molecules is d8. To relate an octahedral fragment, MLn, where M has a dx electron configuration to a square planar analogous fragment, the formula MLn−2 where M has a dx+2 electron configuration should be followed.

Further examples of the isolobal analogy in various shapes and forms are shown in figure 8.

References

- Hoffmann, R. (1982). "Building Bridges Between Inorganic and Organic Chemistry (Nobel Lecture)" (PDF). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 21 (10): 711–724. doi:10.1002/anie.198207113.

- In reference 10 of his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Hoffmann states that the term "isolobal" was introduced in reference 1e, "Elian, M.; Chen, M. M.-L.; Mingos, D. M. P.; Hoffmann, R. (1976). "Comparative bonding study of conical fragments". Inorg. Chem. 15 (5): 1148–1155. doi:10.1021/ic50159a034.", but that the concept is older.

- "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1981: Kenichi Fukui, Roald Hoffmann". nobelprize.org. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- Department of Chemistry. Modern Approaches to Inorganic Bonding. University of Hull.

- Gispert, Joan Ribas (2008). Coordination Chemistry. Wiley-VCH. pp. 172–176.

- Shriver, D.F.; Atkins, P.; Overton, T.; Rourke, J.; Weller, M.; Armstrong, F. (2006). Inorganic Chemistry. Freeman.

- Miessler, G. L.; Tarr, D. A. (2008). Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Pearson Education.

- Douglas, B.; McDaniel, D.; Alexander, J. (1994). Concepts and Models of Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Wiley & Sons.