Isabella Macdonald Alden

Isabella Macdonald Alden (nickname and pen name, Pansy; November 3, 1841 – August 5, 1930) was an American author. Her best known works were: Four Girls at Chautauqua, Chautauqua Girls at Home, Tip Lewis and his Lamp, Three People, Links in Rebecca's Life, Julia Ried, Ruth Erskine's Crosses, The King's Daughter, The Browning Boys, From Different Standpoints, Mrs. Harry Harper's Awakening, The Measure, and Spun from Fact.[1]

Isabella Macdonald Alden | |

|---|---|

Isabella Macdonald Alden | |

| Born | Isabella Macdonald November 3, 1841 Rochester, New York, U.S. |

| Died | August 5, 1930 (aged 88) Palo Alto, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Cypress Lawn Memorial Park |

| Pen name | Pansy |

| Occupation | Author |

| Language | English |

| Spouse |

Gustavus Rossenberg Alden

(m. 1866) |

| Children | Raymond Macdonald Alden (son) |

She also wrote the primary lesson department of the Westminster Teacher, edited the Presbyterian Primary Quarterly and the children's magazine Pansy, and wrote a serial story for the Herald and Presbyter of Cincinnati every winter. Alden was interested in Sunday school primary teaching, and had charge of more than a hundred children every Sunday for many years. She was interested in temperance also, and was involved in the Woman's Christian Temperance Union.[2] Four of her books, Three People, The King's Daughter, One Commonplace Day, and Little Fishers and their Nets, were distinctively temperance books, while the principle of total abstinence was maintained in all her writings.[3]

Early life and education

Isabella Macdonald was born in Rochester, New York to well-educated parents, Isaac and Myra Spafford Macdonald.[4] Her father was a temperance man with pronounced convictions upon subjects regarding social reform, as well as an abolitionist, believing slavery to be a sin. Her mother was devoted to everything that was "pure and of good report."[5]

The sixth of seven children, she was initially home-schooled by her father, who also gave her the nickname Pansy, because of an incident that occurred in her childhood. Her mother had taken great pride in a bed of pansy blossoms. Macdonald, seeing the flowers, and thinking there was no one more deserving of them than her mother, picked them and threw them into her mother's lap exclaiming, "I pulled every one for you." She could not understand her mother's look of distress. The father, seeing the disappointed look on the little girl's face, picked her up, seated her on his shoulder and said, "Never mind, baby, you shall always be my little pansy-blossom."[6]

She developed her writing skills early: as a child, she kept a daily journal which her father critiqued. The letters she wrote to absent family members formed a habit of expressing her thoughts which proved to be useful in her career. When she was ten years old, she wrote a story titled Our Old Clock. The father said the story must be printed in order to preserve it and that she might sign her pet name "Pansy" to it. The child was delighted to see something of her own writing in print.[6]

She was educated at Seneca Collegiate Institute, Ovid, New York and Young Ladles' Institute, Auburn, New York.[4]

Marriage

She met Reverend Gustavus Rossenberg Alden at Oneida Seminary in New York. His work took the couple to various parts of the country, including Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Washington D.C.[2] After their marriage in 1866,[7][4] Alden divided her time among writing, participating in church activities, teaching at several of the Chautauqua sessions, and raising her son, Raymond Macdonald Alden, who was born in 1873. By 1900, the family had three residences: a home in Philadelphia; a summer residence in Chautauqua, New York; and a winter home in Winter Park, Florida.[2]

Literary works

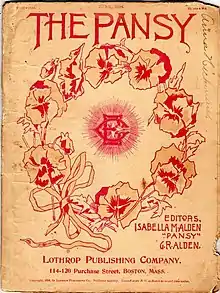

Alden's first book, Helen Lester, was written for a contest at age twenty.[2] She wrote approximately 75 Sunday school books and a number of volumes of fiction for older readers, as well as The Prince of Peace, a life of Christ.[2] She wrote on the subjects of love to God and love to her fellow-men, dedicating her work to the advancement of the Christian religion in the home life and in the business life. She served as president of the Missionary Society, superintendent of the primary department of the Sunday School, identified with the Chautauqua assemblies, and prepared the Sunday School lessons for the Westminster Teacher. Her works were translated into Swedish, French, Japanese, and Armenian. Alden edited the Juvenile periodical Pansy, 1873–96. For many years, she was a contributor to Herald and Presbyter (Cincinnati) and Christian Endeavor World (Boston) besides the Primary Quarterly.[8]

Throughout her life, Alden combined her writing and her religion. She did much work with Christian periodicals, writing serialized stories for the Herald and Presbyter from about 1870 until 1900; editing The Pansy, a Sunday juvenile, from 1874 to 1896; editing the Primary Quarterly and producing the primary-grade Sunday School lessons for the Westminster Teacher for 20 years; and working on the editorial staff of Trained Motherhood and The Christian Endeavor World.[2]

From 1865 to 1929, Alden published about 100 books. Most of her works are didactic fiction with religious principles, which concentrate on translating Biblical precepts into acceptable Christian behavior in a modern world. Several of her books, such as her most popular work Ester Ried, were based on personal experiences; others, such as the Chautauqua Girls series, were motivated by her interest in the Chautauqua movement.[2]

She and her niece, Grace Livingston Hill, even make a brief appearance in the final chapter of the series' last book, Four Mothers at Chatauqua.

Alden's books were enormously popular during the late 19th century. In 1900, sales were estimated at 100,000 copies annually.

Personal life

Alden was a constant sufferer from headache, which never left her and was often very severe, but she refused to call herself an "invalid".[2] Her physician limited her to three hours of literary work each day.[3]

After the deaths of her husband and son in 1924, Alden moved to Palo Alto, California,[4] to live with her daughter-in-law and grandchildren.[2] She continued writing until shortly before her death on August 5, 1930; the unfinished autobiography she left, Memories of Yesterday, was completed and edited by her niece, Grace Livingston Hill.

In the 1990s, edited and abridged editions of some Alden's works appeared in two series issued by Christian publishers, The Pansy Collection, published by Creation Books, and the Grace Livingston Hill Library, published by Living Books.

Selected works

Ester Ried series

- Ester Ried: Asleep and Awake (1870)

- Julia Ried: Listening and Led (1872)

- The King's Daughter (1873)

- Wise and Otherwise (1873)

- Ester Ried Yet Speaking (1883)

- Ester Ried's Namesake (1906)

Chautauqua Girls series

- Four Girls at Chautauqua (1876)

- The Chautauqua Girls at Home (1877)

- Ruth Erskine's Crosses (1879)

- Judge Burnham's Daughters (1888)

- Workers Together, or, An Endless Chain

- Ruth Erskine's Son (1907)

- Four Mothers at Chautauqua (1913)

Paired books

- Chrissy's Endeavor, followed by Her Associate Members

- Household Puzzles, followed by The Randolphs

- Aunt Hannah and Martha and John, followed by John Remington, Martyr

Others

- Three People (1871)

- From Different Standpoints (1878)

- Links in Rebecca's Life (1878)

- The Hall in the Grove (1882)

- Eighty-Seven (1887)

- Pansy's Sunday Book: For afternoon readers, gems of literature and art, with numerous illustrations (Boston: Lothrop Publishing Co., 1896), illustrated M. L. Kirk, Childe Hassam, L. J. Bridgman, Kemble, E. Pollak

- Divers Women

- Interrupted, also published as Out in the World

- Little Fishers and Their Nets

- Mag & Margaret

- The Man of the House

- Rueben's Hindrances

- Spun from Fact

- Tip Lewis and His Lamp

- Memories of Yesterday

References

- Rutherford 1894, p. 64.

- Hinman, Catherine; Mould, Kimberley; Creel, Daena (2019). "WHERE PANSY BLOOMED". Winter Park Magazine. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- Willard & Livermore 1893, p. 14.

- Leonard & Marquis 1908, p. 19.

- Rutherford 1894, p. 651.

- Rutherford 1894, p. 651-52.

- Coyle 1962, p. 6.

- Rutherford 1894, p. 653.

Attribution

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Leonard, John William; Marquis, Albert Nelson (1908). Who's who in America. Marquis Who's Who.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Leonard, John William; Marquis, Albert Nelson (1908). Who's who in America. Marquis Who's Who. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Rutherford, Mildred Lewis (1894). American Authors: A Hand-book of American Literature from Early Colonial to Living Writers (Public domain ed.). Franklin printing and publishing Company.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Rutherford, Mildred Lewis (1894). American Authors: A Hand-book of American Literature from Early Colonial to Living Writers (Public domain ed.). Franklin printing and publishing Company. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Willard, Frances Elizabeth; Livermore, Mary Ashton Rice (1893). "Isabella Macdonald Alden". A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life (Public domain ed.). Moulton.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Willard, Frances Elizabeth; Livermore, Mary Ashton Rice (1893). "Isabella Macdonald Alden". A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life (Public domain ed.). Moulton.- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Bibliography

- Coyle, William (1962). Ohio Authors and Their Books: Biographical Data and Selective Bibliographies for Ohio Authors, Native and Resident, 1796-1950. World Publishing Company.