Irish Wolfhound

The Irish Wolfhound is a breed of large sighthound that has, by its presence and substantial size, inspired literature, poetry and mythology.[5][6][7] Strongly associated with Gaelic Ireland and Irish history, they were famed as guardian dogs and for hunting wolves.

| Irish Wolfhound | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_Irish_Wolfhound_4.jpg.webp) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other names |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Origin | Ireland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dog (domestic dog) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The modern breed, classified by recent genetic research into the Sighthound United Kingdom Rural Clade (Fig. S2),[8] is used by coursing hunters who have prized it for its ability to dispatch game caught by other, swifter sighthounds.[9][10] It is among the largest of all breeds of dog. In 1902, the Irish Wolfhound was declared the regimental mascot of the Irish Guards.[11]

History

Pre-19th century

In 391, there is a reference to large dogs by Quintus Aurelius Symmachus, a Roman Consul who got seven "canes Scotici" as a gift to be used for fighting lions and bears, and who wrote "all Rome viewed (them) with wonder".[12] Scoti is a Latin name for the Gaels (ancient Irish).[13] Dansey, the early 19th century translator of the first complete version of Arrian's work in English, On Coursing, suggested the Irish and Scottish "greyhounds" were derived from the same ancestor, the vertragus, and had expanded with the Scoti from Ireland across the Western Isles and into what is today Scotland.[14]

The dog-type is imagined by some to be very old. Wolfhounds were used as hunting dogs by the Gaels, who called them Cú Faoil[15][16] (Irish: Cú Faoil [ˌkuː ˈfˠiːlʲ], composed of the elements "hound"[17] and "wolf",[18] i.e. "wolfhound"). Dogs are mentioned as cú in Irish laws and literature dating from the sixth century or, in the case of the Sagas, from the old Irish period, AD 600–900. The word cú was often used as an epithet for warriors as well as kings, denoting that they were worthy of the respect and loyalty of a hound. Cú Chulainn, a mythical warrior whose name means "hound of Culann", is supposed to have gained this name as a child when he slew the ferocious guard dog of Culann. As recompense he offered himself as a replacement.[16]

In discussing the systematic evidence of historic dog sizes in Ireland, the Irish zooarchaeologist Finbar McCormick stressed that no dogs of Irish Wolfhound size are known from sites of the Iron Age period of 1000 BC through to the early Christian period to 1200 AD. On the basis of the historic dog bones available, dogs of current Irish Wolfhound size seem to be a relatively modern development: "it must be concluded that the dog of Cú Chulainn was no larger than an Alsatian and not the calf-sized beast of the popular imagination".[19]

Hunting dogs were coveted and were frequently given as gifts to important personages and foreign nobles. King John of England, in about 1210, presented an Irish hound named Gelert to Llywelyn, the Prince of Wales. The poet The Hon William Robert Spencer immortalized this hound in a poem.[16]

In his Historie of Ireland, written in 1571, Edmund Campion gives a description of the hounds used for hunting wolves in the Dublin and Wicklow mountains. He says: "They (the Irish) are not without wolves and greyhounds to hunt them, bigger of bone and limb than a colt". Due to their popularity overseas many were exported to European royal houses leaving numbers in Ireland depleted. This led to a declaration by Oliver Cromwell being published in Kilkenny on 27 April 1652 to ensure that sufficient numbers remained to control the wolf population.[20][21]

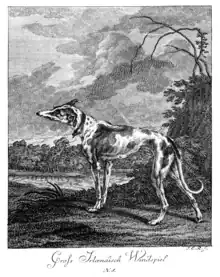

References to the Irish Wolfhound in the 18th century tell of its great size, strength and greyhound shape as well as its scarcity. Writing in 1790, Thomas Bewick described it as the largest and most beautiful of the dog kind; about 36 inches high, generally of a white or cinnamon colour, somewhat like the Greyhound but more robust. He said that their aspect was mild, disposition peaceful, and strength so great that in combat the Mastiff or Bulldog was far from being an equal to them.[22]

The last wolf in Ireland was killed in County Carlow in 1786.[22][24][25] It is thought to have been killed at Myshall, on the slopes of Mount Leinster, by a pack of wolfdogs kept by a Mr Watson of Ballydarton. The wolfhounds that remained in the hands of a few families, who were mainly descendants of the old Irish chieftains, were now symbols of status rather than used as hunters, and these were said to be the last of their race.[22]

Thomas Pennant (1726–1798) reported that he could find no more than three wolfdogs when he visited Ireland. At the 1836 meeting of the Geological Society of Dublin, John Scouler presented a paper titled "Notices of Animals which have disappeared from Ireland", including mention of the wolfdog.[23]

Modern wolfhound

Captain George Augustus Graham (1833–1909) was responsible for reviving the Irish wolfhound breed. He stated that he could not find the breed "in its original integrity" to work with:

That we are in possession of the breed in its original integrity is not pretended; at the same time it is confidently believed that there are strains now existing that tracing back, more or less clearly, to the original breed; and it appears to be tolerably certain that our Deerhound is descended from that noble animal, and gives us a fair idea of what he was, though undoubtedly considerably his inferior in size and power.

— Captain G. A. Graham[26]

Based on the writings of others, Graham had formed the opinion that a dog resembling the original Irish wolfhound could be recreated through using the biggest and best examples of the Scottish Deerhound and the Great Dane, two breeds which he believed had been derived earlier from the wolfhound.[27][28][29] For an outbreed, he used the Duchess of Newcastle's Borzoi, who had earlier proved his wolf-hunting ability in his native Russia, and a "Tibetan wolf-dog", which was probably a Tibetan Kyi Apso.[30] Graham had previously travelled to County Kilkenny, Ireland in the 1860s where he acquired several sires, which were claimed to be descended from original Irish wolfhounds. They were the respective progenitors of his breeding program, but with a gene-pool too small he was forced to outbreed (as per the above).[31][32][33]

In 1885, Captain Graham founded the Irish Wolfhound Club, and the Breed Standard of Points to establish and agree the ideal to which breeders should aspire.[20][34] In 1902, the Irish Wolfhound was declared the regimental mascot of the Irish Guards.[11]

The Irish Wolfhound is a national symbol of Ireland and is sometimes considered the national dog of Ireland.[35] It has also been adopted as a symbol by both rugby codes. The national rugby league team is nicknamed the Wolfhounds, and the Irish Rugby Football Union, which governs rugby union, changed the name of the country's A (second-level) national team in that code to the Ireland Wolfhounds in 2010. One of the symbols that the tax authorities in Ireland have on their revenue stamps has been the Irish wolfhound. In the video game The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, the Irish Wolfhound is the breed of dog for all dogs in the base game.

WWI recruitment poster

WWI recruitment poster National Geographic illustration showing the great size of the breed

National Geographic illustration showing the great size of the breed An Ireland revenue stamp with a picture of an Irish wolfhound

An Ireland revenue stamp with a picture of an Irish wolfhound Champion Irish Wolfhound Patrick of Ifold, Ulster Museum

Champion Irish Wolfhound Patrick of Ifold, Ulster Museum Member of the Irish Guards, pictured at Waterford Barracks with the regiment's mascot, an Irish Wolfhound named Leitrim Boy

Member of the Irish Guards, pictured at Waterford Barracks with the regiment's mascot, an Irish Wolfhound named Leitrim Boy Irish Guards' mascot in parade dress

Irish Guards' mascot in parade dress.jpg.webp) Irish Guard's mascot, 1911

Irish Guard's mascot, 1911 The O'Mahony of Kerry with his Irish Wolfhound

The O'Mahony of Kerry with his Irish Wolfhound

DNA analysis

Genomic analysis indicates that although there has been some DNA sharing between the Irish wolfhound with the Deerhound, Whippet, and Greyhound, there has been significant sharing of DNA between the Irish Wolfhound and the Great Dane.[36] One writer has stated that for the Irish Wolfhound, "the Great Dane appearance is strongly marked too prominently before the 20th Century".[23] George Augustus Graham created the modern Irish wolfhound breed by retaining the appearance of the original form, but not its genetic ancestry.[24]

Characteristics

The Irish Wolfhound is characterised by its large size. According to the FCI standard, the expected range of heights at the withers is 81–86 centimetres (32–34 inches); minimum heights and weights are 79 cm (31 in)/54.5 kg (120 lb) and 71 cm (28 in)/40.5 kg (89 lb) for dogs and bitches respectively.[1] It is more massively built than the Scottish Deerhound, but less so than the Great Dane.[1]

The coat is hard and rough on the head, body and legs, with the beard and the hair over the eyes particularly wiry. It may be black, brindle, fawn, grey, red, pure white, or any colour seen in the Deerhound.[1]

The Irish Wolfhound is a sighthound, and hunts by visual perception alone. The neck is muscular and fairly long, and the head is carried high.[1] It should appear to be longer than it is tall,[37] and to be capable of catching and killing a wolf.[38]

An Irish Wolfhound puppy

An Irish Wolfhound puppy Irish Wolfhound running

Irish Wolfhound running.jpg.webp) Irish Wolfhound with tricolor coat

Irish Wolfhound with tricolor coat Frontal of Irish Wolfhound

Frontal of Irish Wolfhound

Temperament

Irish Wolfhounds have a varied range of personalities and are most often noted for their personal quirks and individualism.[39] An Irish Wolfhound, however, is rarely mindless, and, despite its large size, is rarely found to be destructive in the house or boisterous. This is because the breed is generally introverted, intelligent, and reserved in character. An easygoing animal, the Irish Wolfhound is quiet by nature. Wolfhounds often create a strong bond with their family and can become quite destructive or morose if left alone for long periods of time.[40]

The Irish Wolfhound makes for an effective and imposing guardian. The breed becomes attached to both owners and other dogs they are raised with and is therefore not the most adaptable of breeds. Bred for independence, an Irish Wolfhound is not necessarily keen on defending spaces. A wolfhound is most easily described by its historical motto, "gentle when stroked, fierce when provoked".[40]

They should not be territorially aggressive to other domestic dogs but are born with specialized skills and, it is common for hounds at play to course another dog. This is a specific hunting behavior, not a fighting or territorial domination behavior. Most Wolfhounds are very gentle with children. The Irish Wolfhound is relatively easy to train. They respond well to firm, but gentle, consistent leadership. However, historically these dogs were required to work at great distances from their masters and think independently when hunting rather than waiting for detailed commands and this can still be seen in the breed.[41]

Irish Wolfhounds are often favored for their loyalty, affection, patience, and devotion. Although at some points in history they have been used as watchdogs, unlike some breeds, the Irish Wolfhound is usually unreliable in this role as they are often friendly toward strangers, although their size can be a natural deterrent. However, when protection is required this dog is never found wanting. When they or their family are in any perceived danger they display a fearless nature. Author and Irish Wolfhound breeder Linda Glover believes the dogs' close affinity with humans makes them acutely aware and sensitive to ill will or malicious intentions leading to their excelling as a guardian rather than guard dog.[42]

Health

Like many large dog breeds, Irish Wolfhounds have a relatively short lifespan. Published lifespan estimations vary between 6 and 10 years with 7 years being the average. Dilated cardiomyopathy and bone cancer are the leading cause of death and like all deep-chested dogs, gastric torsion (bloat) is common; the breed is affected by hereditary intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.[43]

In a privately funded study conducted under the auspices of the Irish Wolfhound Club of America and based on an owner survey, Irish Wolfhounds in the United States from 1966 to 1986 lived to a mean age of 6.47 and died most frequently of bone cancer.[44] A more recent study by the UK Kennel Club puts the average age of death at 7 years.[45]

Studies have shown that neutering is associated with a higher risk of bone cancer in various breeds,[46][47][48] with one study suggesting that castration should be avoided.[43]

References

- FCI-Standard N° 160: Irish Wolfhound. Fédération Cynologique Internationale. Accessed April 2021.

- Manfield, Mark (2019). Irish Wolfhound Bible And Irish Wolfhounds.

- "2004 Pedigree Dog Health Survey" (PDF). The Kennel Club. The Kennel Club. 2004. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- National Research Council (2001). Cells and Surveys. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-309-07199-4.

- DeQuoy, Alfred W. (1971). The Irish Wolfhound in Irish literature and law. ASIN B003S8E6J2.

- Scharff, R. F. (August 1924). "On the breeds of dogs peculiar to Ireland and their origin". The Irish Naturalist. 33 (8): 77–88. JSTOR 25525370 – via JSTOR.

- Hogan, Edmund I. (1897). The History of the Irish Wolfdog. Read Books (published 9 February 2009). ISBN 978-1-4437-9697-2.

- Parker; et al. (2017). "Genomic Analyses Reveal the Influence of Geographic Origin, Migration, and Hybridization on Modern Dog Breed Development". Cell Reports. 19 (4): 697–708. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.079. PMC 5492993. PMID 28445722.

- Almirall, Leon V. (1941). Canines and Coyotes. Caxton Printers, Limited. p. 55. ASIN B0006APB8A.

- Copold, Steve (1977). Hounds, Hares & Other Creatures: The Complete Book of Coursing. Hoflin Publishing. p. 58. OCLC 3071190.

- "Regimental mascots - Irish Guards 1902-1910". www.irishwolfhounds.org. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- Samaha, Joel (1657). The New Complete Irish Wolfhound. Howell Book House (published 15 April 1991). p. 2. ISBN 978-0-87605-171-9.

- Duffy, Seán, ed. (2004). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 698. ISBN 978-0-415-94052-8.

- Arrian (1831). Arrian on coursing: the Cynegeticus of the younger Xenophon, translated from the Greek, with classical and practical annotations, and a brief sketch of the life and writings of the author. To which is added an appendix, containing some account of the Canes venatici of classical antiquity. London: J. Bohne. pp. 297. OCLC 1040021079. OL 17958481M.

- "Wolfhound". www.focloir.ie. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- McBryde, Mary (1998). The Irish Wolfhound: Symbol of Celtic Splendor. John Wiley & Sons. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-87605-169-6.

- cú in Ó Dónaill, Niall (1977). Foclóir Gaeilge-Béarla. Dublin: Richview Browne & Nolan Ltd. ISBN 1-85791-038-9.

- faol in Ó Dónaill, Niall (1977). Foclóir Gaeilge-Béarla. Dublin: Richview Browne & Nolan Ltd. ISBN 1-85791-038-9.

- McCormick, F. (1991). "The Dog in Prehistoric and Early Christian Ireland". Archaeology Ireland. 5 (4): 7–9. JSTOR 20558375.

- Howell, Elsworth S. (1971). The International Encyclopedia of Dogs. McGraw-Hill. pp. 254–255. ISBN 978-0-7015-2969-7.

- McBryde, Mary (1998). The Irish Wolfhound: Symbol of Celtic Splendor. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-87605-169-6.

- McBryde, Mary (1998). The Irish Wolfhound: Symbol of Celtic Splendor. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 27–31. ISBN 978-0-87605-169-6.

- Gordon, John F. (January 1973). The Irish Wolfhound (1st ed.). J. Bartholomew. pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-0-85152-918-9.

- Larson, Greger; Karlsson, Elinor K.; Perri, Angela; Webster, Matthew T. (5 June 2012). "Rethinking Dog Domestication by Integrating Genetics, Archeology, and Biogeography". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (23): 8878–8883. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.8878L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1203005109. PMC 3384140. PMID 22615366.

- Hickey, Kieran R. (2000). "A geographical perspective on the decline and extermination of the Irish wolf canis lupus—an initial assessment" (PDF). Irish Geography. 33 (2): 185–198. doi:10.1080/00750770009478590. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- Graham, G. A. (1885). The Irish Wolfhound. Whitmore & Son. pp. 1.

- Graham, G. A. (1885). The Irish Wolfhound. Whitmore & Son. pp. 23. Do a search on these two breeds, this is the subject of the book.

- Gordon, John F. (January 1973). The Irish Wolfhound (1st ed.). J. Bartholomew. pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-0-85152-918-9.

- Horter, Ria (2014). Masterminds: Capt. George Augustus Graham and the Irish Wolfhound (PDF).

- Hamilton, Ferelith; Jones, Arthur F. (1971). The World Encyclopedia of Dogs (1st ed.). Galahad Books. p. 672. ISBN 978-0-88365-302-9.

- Various (6 September 2016). The Irish Wolfhound - A Complete Anthology of the Dog. Read Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4733-5270-4.

- "Graham to the rescue". www.irishwolfhounds.org. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- Pisano, Beverly (1996). Irish Wolfhounds. TFH Publications, Incorporated. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7938-2372-7.

- Samaha(1991)pp.8-19.

- Jordan, Cath (29 January 2023). "What is the national animal of Ireland?". Travel Around Ireland. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- Parker, Heidi G.; Dreger, Dayna L.; Rimbault, Maud; Davis, Brian W. (2017). "Genomic Analyses Reveal the Influence of Geographic Origin, Migration, and Hybridization on Modern Dog Breed Development". Cell Reports. 19 (4): 697–708. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.079. PMC 5492993. PMID 28445722. Refer Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S2: "Mean Haplotype Sharing Totals that Reach the 95% Significance Level between All Pairs of Breeds"

- McBryde, Mary (1998). The Irish Wolfhound: Symbol of Celtic Splendor. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 107–132. ISBN 978-0-87605-169-6.

- Samaha, Joel (3 May 2019). "Judging Irish Wolfhounds - A Guide". Irish Wolfhound Club of America. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- McBryde, Mary (1998). The Irish Wolfhound: Symbol of Celtic Splendor. John Wiley & Sons. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-87605-169-6.

- McBryde, Mary (1998). The Irish Wolfhound: Symbol of Celtic Splendor. John Wiley & Sons. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-87605-169-6.

- McBryde, Mary (1998). The Irish Wolfhound: Symbol of Celtic Splendor. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 97, 160–162. ISBN 978-0-87605-169-6.

- Glover, Linda (1999). Irish wolfhound (World of Dogs). TFH. ISBN 978-1-85279-077-6.

- Urfer SR, Gaillard C, Steiger A (2007). "Lifespan and disease predispositions in the Irish wolfhound: a review". Vet Q. 29 (3): 102–111. doi:10.1080/01652176.2007.9695233. PMID 17970287. S2CID 38774771.

- Bernardi, Gretchen (1997). "Longevity and Morbidity in the Irish Wolfhound in the United States - 1966 to 1986". Irish Wolfhound Club of America. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "2004 Pedigree Dog Health Survey" (PDF). The Kennel Club. The Kennel Club. 2004. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Priester; McKay, F. W. (1980). "The Occurrence of Tumors in Domestic Animals". Journal of the National Cancer Institute (54): 1–210. PMID 7254313.

- Ru, G.; Terracini, B.; Glickman, L. (1998). "Host related risk factors for canine osteosarcoma". The Veterinary Journal. 156 (1): 31–9. doi:10.1016/S1090-0233(98)80059-2. PMID 9691849.

- Cooley, D. M.; Beranek, B. C.; et al. (1 November 2002). "Endogenous gonadal hormone exposure and bone sarcoma risk". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 11 (11): 1434–40. PMID 12433723.

Further reading

- Landau, Elaine (2011). Irish Wolfhounds Are the Best. Lerner Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-7613-6081-0.

- McBryde, Mary (1998). The Irish Wolfhound: Symbol of Celtic Splendor. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-87605-169-6.

- Samaha, Joel (1991). The New Complete Irish Wolfhound. Howell Book House. ISBN 978-0-87605-171-9.

- Gardner, Phyllis; Gardner, Delphis (1931). The Irish Wolfhound. A Short Historical Sketch... With Over One Hundred Wood Engravings Specially Cut by the Author and Her Sister Delphis. Dundalgan Press. (reprint 1981 by Elizabeth C. Murphy, ISBN 0-85221-104-X)

External links

Media related to Irish Wolfhound at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Irish Wolfhound at Wikimedia Commons