Irene Papas

Irene Papas or Irene Pappas[3] (Greek: Ειρήνη Παππά, romanized: Eiríni Pappá, IPA: [iˈrini paˈpa]; born Eirini Lelekou (Greek: Ειρήνη Λελέκου, romanized: Eiríni Lelékou); 3 September 1929 – 14 September 2022)[4] was a Greek actress and singer who starred in over 70 films in a career spanning more than 50 years. She gained international recognition through such popular award-winning films as The Guns of Navarone (1961), Zorba the Greek (1964) and Z (1969). She was a powerful protagonist in films including The Trojan Women (1971) and Iphigenia (1977). She played the title roles in Antigone (1961) and Electra (1962). She had a fine singing voice, on display in the 1968 recording Songs of Theodorakis.

Irene Papas | |

|---|---|

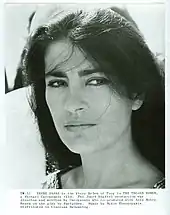

Papas in 1956 | |

| Born | Irene Lelekou 3 September 1929 |

| Died | 14 September 2022 (aged 93) |

| Resting place | Chiliomodi Cemetery, Corinthia, Greece |

| Nationality | Greek |

| Occupation(s) | Film and theatre actress, singer |

| Years active | 1948–2003 |

| Known for | Heroines of Greek tragedy;[1] powerful stage presence[2] |

| Notable work | The Guns of Navarone Zorba the Greek Z The Trojan Women Iphigenia Antigone Electra |

| Spouses | |

| Relatives | Manousos Manousakis (nephew) |

Papas won Best Actress awards at the Berlin International Film Festival for Antigone and from the National Board of Review for The Trojan Women. Her career awards include the Golden Arrow Award in 1993 at Hamptons International Film Festival, and the Golden Lion Award in 2009 at the Venice Biennale.

Early life

Papas was born as Eirini Lelekou (Ειρήνη Λελέκου) on 3 September 1929,[lower-alpha 1][4][7][8] in the village of Chiliomodi, outside Corinth, Greece. Her mother, Eleni Prevezanou (Ελένη Πρεβεζάνου), was a schoolteacher, and her father, Stavros Lelekos (Σταύρος Λελέκος),[lower-alpha 2] taught classical drama at the Sofikós school in Corinth.[5] She recalled that she was always acting as a child, making dolls out of rags and sticks; after a touring theatre visited the village performing Greek tragedies with the women tearing their hair, she used to tie a black scarf around her head and perform for the other children.[11] The family moved to Athens when she was seven years old.[12] She was educated from age 15 at the National Theatre of Greece Drama School in Athens, taking classes in dance and singing.[5] She found the acting style advocated by the School old-fashioned, formal, and stylised, and she rebelled against it, causing her to have to repeat a year; she eventually graduated in 1948.[12]

Career

Theatre

Papas began her acting career in Greece in variety and traditional theatre, in plays by Ibsen, Shakespeare, and classical Greek tragedy, before moving into film in 1951.[5] She continued to appear on stage from time to time, including in New York City in productions such as Dostoevsky's The Idiot.[13] She played in Iphigenia in Aulis in Broadway's Circle in the Square Theatre in 1968.[14]

She starred in Medea in 1973 on Broadway. Reviewing the production in the New York Times, drama critic Clive Barnes described her as a "very fine, controlled Medea", smouldering with a "carefully dampened passion", constantly fierce.[15] Theatre critic Walter Kerr also praised the performance. Both saw in her portrayal what Barnes called an "unrelenting determination and unwavering desire for justice".[1] She appeared in The Bacchae in 1980 at Circle in the Square,[16] and in Electra at the Ancient Theatre of Epidaurus in 1985.[17]

Europe

Papas was discovered by Elia Kazan in Greece, where she achieved widespread fame.[5][19] Her first film work was a small part in Nikos Tsiforos's 1948 Fallen Angels (Greek, "Hamenoi angeloi").[20] She began to attract attention with her role in Frixos Iliadis's 1952 film Dead City (Greek, "Nekri Politeia"). The film was shown at the Cannes Film Festival, where Papas was welcomed by the international press, and photographed spending time with the wealthy Aga Khan.[21][19][22] Greek filmmakers thought her a noncommercial actress, and she tried her hand abroad, signing with Lux Film in Italy, where the publicity for Dead City was enough to launch her as a film star. She played in Lux's 1954 films Attila and Theodora, Slave Empress, which attracted Hollywood's attention.[11] Many other films followed, both in Greece and internationally.[21][19][22]

She was a leading figure in cinematic transcriptions of ancient tragedy, playing the title roles in George Tzavellas's Antigone (1961) and Michael Cacoyannis's Electra (1962), with her powerful portrayal of the doomed heroine; this brought her star status.[18] She played Helen in Cacoyannis's The Trojan Women (1971) opposite Katharine Hepburn, and Clytemnestra with "smoldering eyes", according to The New York Times,[23] in his Iphigenia (1977).[21][19][24]

Papas became fluent in Italian, and many of her films were made in that language. She said Cacoyannis was the only director that she was really comfortable with, describing herself as "too obedient" to stand up to other directors.[11] Cacoyannis said that she was part of his decision to make Iphigenia, forming his image of Clytemnestra with her power and physique, and her un-selfpitying, impersonal anger against the injustice of life, something that in his view was accessible to actors from countries like Greece that had experienced long years of oppression.[18]

Alejandro Valverde García described Papas's part in The Trojan Women as "the most convincing cinematographic Helen that has ever been represented", noting that the script was written with her in mind.[25]

Hollywood

Papas debuted in American film with a bit part in the B-movie The Man from Cairo (1953); her next American film was a much larger role as Jocasta Constantine, alongside James Cagney, in the Western Tribute to a Bad Man (1956).[26] She then starred in films such as The Guns of Navarone (1961) and Cacoyannis's Zorba the Greek (1964), based on Nikos Kazantzakis's novel of the same name, set to Mikis Theodorakis's music, establishing her reputation internationally.[17][27][18]

In The Guns of Navarone, she stars as a resistance fighter involved in the action, an addition to Alistair Maclean's novel, providing a love interest and a strong female character.[28][29][30] Gerasimus Katsan comments that she plays a "hard as nails" partisan in The Guns of Navarone, "capable, unafraid, stoic, patriotic, and heroic"; when the men hesitate, she kills the traitorous Anna; but although she interacts romantically with Andreas (Anthony Quinn), she remains "cool and rational", revealing little of her sensual persona; she is as tough as the men, like the stereotype of a Greek village woman, but she is contrasted with them in the film.[26]

Bosley Crowther called her appearance in Zorba "dark and intense as the widow".[31] Katsan said that she was most often remembered as the "sensual widow" in Zorba.[26] Katsan wrote that she was again contrasted to the other village women, playing "the beautiful and tortured widow" who is eventually hunted to death with what Vrasidas Karalis called "elemental nobility".[26][32] The scholar of film Jefferson Hunter wrote that Papas helped lift Zorba from being merely an "exuberant" film with the stark passion of her subplot role.[33]

This success did not earn her an easy life; she stated that she did not work for 2 years after Electra, despite the prizes and acclamation; and again, she was out of work for 18 months after Zorba. It turned out to be her most popular film, but she said she earned only $10,000 from it.[11]

Papas played leading roles in critically acclaimed films such as Z (1969), where her political activist's widow has been called "indelible".[27] She appeared as Catherine of Aragon in Anne of the Thousand Days, opposite Richard Burton and Geneviève Bujold in 1969. In 1976, she starred in Mohammad, Messenger of God about the origin of Islam. In 1982, she appeared in Lion of the Desert. One of her last film appearances was in Captain Corelli's Mandolin in 2001,[5][34] where in Katsan's view she was underused reprising her strong peasant woman from The Guns of Navarone and the widow from Zorba.[26]

Stardom

The Enciclopedia Italiana described Papas as a typical Mediterranean beauty, with a lovely voice both in singing and acting, greatly talented and with an adventurous spirit.[5] Olga Kourelou added that film-makers from Cacoyannis onwards have made systematic use of her looks: "Her chalk-white skin and long black hair, dark brown eyes, thick arched eyebrows, and straight nose make Papas appear as the quintessential idea of Greek beauty." She writes that the camera has lingered in close-up on Papas's face, and that she is often photographed in profile, intentionally recalling the iconography of ancient Greece. Kourelou gives as example the profile shot in Iphigenia where Papas sings a lullaby to her daughter, in front of a Hellenic sculpture of a woman, the shot bringing out the resemblance of their facial features; she notes that posters of Papas have often used the same motif.[12]

Gerasimus Katsan wrote that she is the best-known and most recognisable Greek film star, "an actor with incredible range, power, and subtlety".[26] In the view of the film critic Philip Kemp,[21]

From the opening shot of Michael Cacoyannis's Electra, as the proud, implacable face emerges from encroaching shadows, it becomes impossible to imagine anyone else as Euripides's heroine. Erect, immutably dignified, dark eyes burning fiercely beneath heavy black brows, Irene Papas visibly embodies the sublimity of classical Greece, tragic yet serene.[21]

Kemp described Papas as an awe-inspiring presence, which paradoxically limited her career. He admired her roles in Cacoyannis's films, including the defiant Helen of Troy in The Trojan Women; the vengeful, grief-stricken Clytemnestra in Iphigenia; and "memorably"[21][19] as the cool but sensual widow in Zorba the Greek.[19] David Thomson, in his Biographical Dictionary of Film, called Papas's manner in Iphigenia "blatant declaiming".[35] She stood out, too, in Costa-Gavras's 1968 political film Z based on a real-life assassination, and in Ruy Guerra's 1983 Eréndira, with a screenplay by the novelist Gabriel García Márquez.[18]

The film critic Roger Ebert observed that there were many "pretty girls" in cinema "but not many women", and called Papas a great actress. Ebert noted her uphill struggle, her height, 5 feet 10 inches (1.78 m) limiting the leading men she could play alongside, her accent limiting the roles she could take, and that "her unusual beauty is not the sort that superstar actresses like to compete with."[36][37] Ordinary actors, he suggested, had trouble sharing the screen with Papas. All the same, her presence in many well-known movies, wrote Ebert, inspired "something of a cult".[36]

In his book on Greek cinema, Mel Schuster called Papas a great actress on the strength of her roles in four of Cacoyannis's films. He found her stage presence awe-inspiring, especially in Electra, and so powerful as to limit the film roles she could take, as she seemed to be an elemental force of nature. That resulted, Schuster stated, in Hollywood's treating her as "a Mother Earth who suffered and survived, but rarely talked or acted".[2] That made her Helen in The Trojan Women, pacing up and down like a caged panther "with just the searching eyes darting through the bars", a "marvelous surprise", as Hollywood saw that in fact she was also an accomplished actor.[2] In his view, casting her as the beautiful Helen was daring, as Papas was not, in 1971, as conventionally beautiful as a Hedy Lamarr or an Elizabeth Taylor; if she was the face that launched a thousand ships, then she brought "a force which might indeed have inspired a holocaust".[2] Schuster commented that in each of the four Cacoyannis films, one shot of Papas's gave "indelible pleasure" and remained etched in the memory. In Iphigenia, that shot was in his view wisely placed at the end, under the closing credits, so that viewers see her until that moment as a versatile and powerfully histrionic actress, appropriate both to the ancient mythic dimensions of the tale and to a modern psychological reading of the myth.[2]

Bella Vivante contrasted Papas's dark-haired Helen in The Trojan Women with the conventional choice of a blonde, Rossana Podestà, in Robert Wise's 1956 Helen of Troy. Where Wise emphasised Helen's seductive gaze and framed Podesta as an ideal beauty for the audience to look at, Cacoyannis made the scenes framed as Papas's gaze provide "an empowering female identity".[38]

The scholar of Greek, Gerasimus Katsan, called her the most recognizable and best-known Greek film star, with "range, power, and subtlety", stating that her work made her a kind of national hero. She acted strong women with "beauty and sensuality, but also fierce independence and spirit".[26]

Robert Stam wrote of Papas's role in Ruy Guerra's 1983 Eréndira that "the near-indestructible grandmother [of the eponymous young prostitute] reigns supreme"; she gives the effect of "a kind of queen" both through the regal props and her powerful performance, at once villainous and sympathetic, "an oracle who speaks truths, especially about men and love".[39]

Kourelou wrote that although Papas had appeared in the films of both European and American "auteurs", she was best known as a tragedienne, citing the film-maker Manoel de Oliveira's remark that "this great tragedienne is the grand and beautiful image that embodies the deepest essence of the female soul. She is the image of Greece of all time ..., the mother of western civilisation".[12] In Kourelou's view, Papas's tragic persona "offers an image of sublimated beauty with a transcendental quality";[12] she notes that Papas is neither "sexualised nor glamorised" with the single exception of her role as Helen in The Trojan Women.[12]

In 1973, she was honoured with a photo shoot by the Magnum photographer Ferdinando Scianna.[40]

Asked about her acting for film and stage, and in classical and modern films, Papas stated that the acting techniques and method of expressing oneself are the same. One might, she said, need to use a louder voice on a classical stage, but "you always use the same soul".[18] She denied having any secret to acting with such energy, but said that one's attitude to death was what drove action. Death was in her view "the greatest catalyst in human life"; while waiting to die, one had to decide what to do with one's life.[18]

Singing

In 1969, the RCA label released Papas' vinyl LP, Songs of Theodorakis (INTS 1033). This has 11 songs sung in Greek, conducted by Harry Lemonopoulos and produced by Andy Wiswell, with sleeve notes in English by Michael Cacoyannis. It was released on CD in 2005 (FM 1680).[42] Papas knew Mikis Theodorakis from working with him on Zorba the Greek[19] as early as 1964. The critic Clive Barnes said of her singing performance on the album that "Irene Pappas is known to the public as an actress, but that is why she sings with such intensity, her very appearance, with her raven hair, is an equally dynamic means of expression".[41]

In 1972, she appeared on the album 666 by the Greek rock group Aphrodite's Child on the track "∞" (infinity). She chants "I was, I am, I am to come" repeatedly and wildly over a percussive backing, worrying the label, Mercury, who hesitated over releasing the album, causing controversy with her "graphic orgasm".[43][44]

In 1979, Polydor released her album of eight Greek folk songs entitled Odes, with electronic music performed (and partly composed) by Vangelis.[45] The lyrics were co-written by Arianna Stassinopoulos.[46] They collaborated again in 1986 for Rapsodies, an electronic rendition of seven Byzantine liturgy hymns, also on Polydor; Jonny Trunk wrote that there was "no doubting the power, fire and earthy delights of Papas' voice".[47]

Politics

In 1967, Papas, a lifelong liberal, called for a "cultural boycott" against the "Fourth Reich", meaning the military government of Greece at that time.[48][17] Her opposition to the regime sent her, and other artists such as Mikis Theodorakis, whose songs she sang, into exile when the military junta came to power in Greece in 1967; she moved into temporary exile in Italy and New York.[21][49][50][17] When the junta fell in 1974, she returned to Greece, spending time both in Athens and in her family's village house in Chiliomodi, as well as continuing to work in Rome.[17]

Personal life

In 1947 she married the film director Alkis Papas; they divorced in 1951.[21] In 1954 she met the actor Marlon Brando and they had a long love affair, which they kept secret at the time. Fifty years later, when Brando died, she recalled that "I have never since loved a man as I loved Marlon. He was the great passion of my life, absolutely the man I cared about the most and also the one I esteemed most, two things that generally are difficult to reconcile".[51] Her second marriage was to the film producer José Kohn in 1957; that marriage was later annulled. She was the aunt of the film director Manousos Manousakis and the actor Aias Manthopoulos.[52][16]

In 2003 she served on the board of directors of the Anna-Marie Foundation, a fund which provided assistance to people in rural areas of Greece.[53] In 2013 she began to suffer from Alzheimer's disease.[54] Papas spent her final years in home care at her niece's house in Kifissia, Athens. She died there on 14 September 2022, at the age of 93.[4][7][8]

Awards and distinctions

- 1961: 11th Berlin International Film Festival (Best Actress, for the film Antigone)[55][56]

- 1962: Thessaloniki International Film Festival (Best Actress, for the film Elektra)[57]

- 1971: National Board of Review (Best Actress, for the film The Trojan Women)[58]

- 1987 Venice Film Festival jury president[59]

- 1993: Golden Arrow Award for lifetime achievement, at Hamptons International Film Festival[60]

- 1993: Flaiano Prize for Theatre (Career Award)[61]

- 2009: Leone d'oro alla carriera (Golden Lion career award), Venice Biennale[62]

She received the honours of Commander of the Order of the Phoenix in Greece, Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres in France, and Commander of the Civil Order of Alfonso X, the Wise in Spain.[63]

In 2017, it was announced that the National Theatre of Greece's drama school would move to a new "Irene Papas – Athens School" on Agiou Konstantinou Street in Athens from 2018.[64]

Discography

- 1968 : Songs of Theodorakis, in concert in New York, music conducted by Harry Lemonopoulos[65]

- 1972 : 666 by Aphrodite's Child - Chanted vocals on "∞"[44]

- 1979 : Ωδές – Odes – with Vangelis[66]

- 1986 : Ραψωδίες – Rapsodies – with Vangelis[47]

Filmography

- Fallen Angels (Greek, "Hamenoi angeloi", 1948) as Liana[67]

- Dead City (Greek, "Nekri Politeia", 1951) as Lena[19][21]

- The Unfaithfuls (Italian, "Le Infideli", 1953) as Luisa Azzali[19][21][68]

- Come Back! (Italian, "Torna!", 1953)[69]

- The Man from Cairo (Italian, "Dramma del Casbah", 1953) as Yvonne Lebeau[19]

- Vortex (Italian, "Vortice", 1953) as Clara[19][68]

- Theodora, Slave Empress (Italian, "Teodora, Imperatrice di Bisanzio", 1954) as Faidia[19][68]

- Attila (Italian, "Attila, il flagello di Dio", 1954) as Grune[19][68]

- Tribute to a Bad Man (1956) as Jocasta Constantine[19]

- The Power and the Prize (1956)[19]

- Bouboulina (Greek, 1959) as Laskarina Bouboulina[70]

- The Guns of Navarone (1961) as Maria[19]

- Antigone (Greek, 1961) as Antigone[19][21]

- Electra (Greek, 1962) as Electra[19][21]

- The Moon-Spinners (1964) as Sophia[19]

- Zorba the Greek (1964) as the widow[19]

- Trap for the Assassin (French, "Roger la Honte", 1966) as Julia de Noirville[19]

- Witness out of Hell (German, "Zeugin aus der Hölle", 1966) as Lea Weiss[19]

- We Still Kill the Old Way (Italian, "A ciascuno il suo", 1967) as Luisa Roscio[19][21]

- The Desperate Ones (Spanish, "Más allá de las montañas", 1967) as Ajmi[19][21]

- The Odyssey (Italian, "L'Odissea", 1968, TV Mini-series) as Penelope[19][68]

- The Brotherhood (1968) as Ida Ginetta[19][68]

- Ecce Homo (Italian, "Ecce Homo – I sopravvissuti", 1968) as Anna[71]

- Z (French, 1969) as Helene[19]

- A Dream of Kings (1969) as Caliope[19]

- Anne of the Thousand Days (1969) as Queen Katherine[19]

- The Trojan Women (1971) as Helen of Troy[19]

- Oasis of Fear (Un posto ideale per uccidere, 1971) as Barbara Slater[68]

- Rome Good (Italian, "Roma Bene", 1971) as Elena Teopoulos[19]

- N.P. (Italian, "N.P. – Il segreto", 1971) as the housewife[72]

- Don't Torture a Duckling (Italian, "Non si servizia un paperino", 1972) as Dona Aurelia Avallone[19]

- 1931, Once Upon a Time in New York (1972) as Donna Mimma[19]

- Battle of Sutjeska (Serbian, "Sutjeska", 1973) as Boro's mother[73]

- I'll Take Her Like a Father (Italian, "Le farò da padre", 1974)[68] as Raimonda Spina Tommaselli

- Moses the Lawgiver (Italian, "Mose", 1974) (TV miniseries) as Zipporah[19]

- Mohammad, Messenger of God (Arabic, "Ar-Risālah", 1976) as Hind bint Utbah[19]

- Blood Wedding (Spanish, "Bodas de Sangre", 1977) as the mother[74]

- Iphigenia (Greek, 1977) as Clytemnestra[19]

- The Man of Corleone (Italian, "L'uomo di Corleone", 1977)[21]

- Christ Stopped at Eboli (Italian, "Cristo si e fermato a Eboli", 1979) as Giulia[19][68]

- Bloodline (1979) as Simonetta Palazzi[19]

- Ring of Darkness (Italian, "Un'ombra nell'ombra", 1979) as Raffaella[75]

- Lion of the Desert (Arabic, "Asadu alsahra", 1981) as Mabrouka[19]

- The All Pepper Social Worker (Italian, "L'assistente sociale tutto pepe", 1981)[68] as the fairy

- Manuel's Tribulations (French, "Les Tribulations de Manuel", 1982) (TV series)

- The Ballad of Mameluke (French, "La Ballade de Mamlouk", 1982)[21]

- Eréndira (Mexico, 1983) as the grandmother[19]

- Why Afghanistan? (French, "Afghanistan pourquoi?" 1983)[21] as cultural attaché

- The Deserter (Italian, "Il disertore", 1983) as Mariangela[19]

- In the Shade of the Great Oak (Italian, ""All'ombra della grande quercia, 1984) (TV mini-series)

- Into the Night (Italian, Tutto in una notte, 1985) as Shaheen Parvizi[19][68]

- The Assisi Underground (1985)[76] as Mother Giuseppina

- Sweet Country (1987)[77] as Mrs. Araya

- Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1987)[78][79] as Angela's mother

- High Season (1987)[80] as Penelope

- A Child Named Jesus (Italian, "Un bambino di nome Gesù", 1987) (TV film)[68]

- The Cardboard Suitcase (Portuguese, "A Mala de Cartão", 1988) (TV miniseries), as Maria Amélia

- Plato's Banquet (Italian, "Il banchetto di Platone", 1988)[68] as Diotima

- Island (1989)[81] as Marquise

- The Green-eyed Cavaliers (French, "Les Cavaliers aux yeux verts", 1990) as Anasthasie Rouch

- The Detective Inspector (Italian, "L'ispettore anticrimine", 1993)[68] as Maria

- Stolen Love (Italian, "Amore Rubato", 1993)

- Jacob (1994) (TV film)[76] as Rebeccah

- Party (1996) as Irene[19]

- The Odyssey (1997) (TV miniseries) as Anticlea[19]

- Anxiety ("Inquietude", 1998) as the mother[19]

- Yerma (Spanish, 1998) as the old pagan woman[19]

- Captain Corelli's Mandolin (2001) as Drosoula[34]

- A Talking Picture (2003) as Helena[82]

Notes

- There has been confusion over the date of birth, with the respected Enciclopedia Italiana stating in 1994 that Papas was born on 3 September 1926 rather than 3 September 1929.[5] This error was propagated by other sources (for example, Finos Film[6]). Papas addressed the confusion directly, noting that she had often been described as three years older than she actually was. At the start of an interview on Greek state television in 2004 she said "I was born on Sept. 3, 1929. All the papers are there in Chiliomodi [her home village]".[4]

- There are persistent but vague and unsubstantiated claims of an Albanian connection. Papas stated in an interview, without providing evidence, that "my father probably came from Albania. Maybe I am Albanian, or half Albanian. The Peloponnese is full of Albanians."[9][10]

References

- Hartigan, Karelisa (1995). Greek Tragedy on the American Stage: Ancient Drama in the Commercial Theater, 1882-1994. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 53–55. ISBN 978-0-313-29283-5.

- Schuster, Mel (1979). The Contemporary Greek Cinema. Scarecrow Press. pp. 256–258. ISBN 9780810811966.

- "Irene Pappas Asks Boycott Of Greece's 'Fourth Reich'". The New York Times. 20 July 1967. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- "Greece's Irene Papas, Who Earned Hollywood Fame, Dies At 93". Bloomberg UK, using Associated Press. 14 September 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

She was 93. ... Papas publicly joked that she was often quoted as being three years older than her actual age. She started a 2004 interview with Greek state television by saying, "I was born on Sept. 3, 1929. All the papers are there in Chiliomodi," which is located near the southern Greek city of Corinth.

- "Papas, Irene, nata Lelekou". Enciclopedia Italiana - V Appendice (1994). Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- "Ειρήνη Παππά (Irene Pappas)". FinosFilm. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

Γεννήθηκε: 03 Σεπτεμβρίου 1926 ("Born: 3 September 1926")

- Zee, Michaela (14 September 2022). "Irene Papas, 'Zorba The Greek' and 'Z' Star, Dies at 93". Variety. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- "Irene Papas, Greek Actress Who Earned Hollywood Fame, Dies at 93". The Hollywood Reporter. 14 September 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- "Irene Papas: Jam Shqiptare, Peloponezi është plot me shqiptarë". The Albanian. 4 December 2016. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- Costantini, Costanzo (1997). Le Regine del Cinema [The Queens Of Cinema] (in Italian). Gremese Editore. pp. 135–137. ISBN 978-8877421388.

- Segrave, Kerry; Martin, Linda (1990). The Continental Actress: European film stars of the postwar era – biographies, criticism, filmographies. McFarland. pp. 92–97. ISBN 9780899505107.

- Kourelou, Olga (2020). "'A True Goddess': Irene Papas and the Representation of Greekness". In D. H. Fleming; Cheung Ruby (eds.). Cinemas, Identities and Beyond. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 212–226. ISBN 978-1-5275-5667-6.

- "Irene Papas: The Greatest Greek Actress". Greek Gateway. 4 August 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- "Irene Papas and Christopher Walken in the stage production Iphigenia in Aulis, Circle in the Square, 1968". New York Public Library. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- Barnes, Clive (18 January 1973). "Stage: Circle Presents New 'Medea'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 September 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Gates, Anita (14 September 2022). "Irene Papas, Actress in 'Zorba the Greek' and Greek Tragedies, Dies at 96". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 September 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- Hope, Kerin (14 July 1986). "Irene Papas Wants to Direct Shakespeare". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- McDonald, Marianne; Winkler, Martin M. (2001). "Michael Cacoyannis and Irene Papas on Greek Tragedy". In Martin M. Winkler (ed.). Classical Myth & Culture in the Cinema. Oxford University Press. pp. 72–89. ISBN 978-0-19-513004-1.

- Kemp, Philip. "Papas, Irene". Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- "Irene Papas". Cinemagraphe. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Kemp, Philip (2000). Pendergast, Tom; Pendergast, Sara (eds.). Papas, Irene. pp. 948–949. ISBN 978-1-55862-452-8. OCLC 44818539.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - "ΒΙΟΓΡΑΦΊΕΣ ΘΈΑΤΡΟ - ΚΙΝΗΜΑΤΟΓΡΆΦΟΣ Ειρήνη Παπά" [Theatre - Cinema Biography Irene Papas] (in Greek). Sansimera. Archived from the original on 1 July 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Reed, Rex (24 December 1967). "Irene Doesn't Believe in Irene". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- "Electra/ Elektra". The Sydney Greek Film Festival 2006. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- García, Alejandro Valverde (1971). "A Greek Tragedy against the abuses of power: 'The Trojan Women' (1971) by Michael Cacoyannis". Modern Greek Studies (19): 325–343. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- Katsan, Gerasimus (2016). "The Hollywood Films of Irene Papas". The Journal of Modern Hellenism (32): 31–44. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- Monaco, James (1991). The Encyclopedia of Film. Perigee Books. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-399-51604-7.

- Crowther, Bosley (23 June 1961). "Screen: A Robust Drama:'Guns of Navarone' Is at Two Theatres". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 October 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- Massie, Mike (22 June 1961). "[Review] The Guns of Navarone (1961)". Gone with the Twins. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- Miller, Andrew C. (30 June 2019). "[Review] The Guns of Navarone". Le Cinema Paradiso. Archived from the original on 14 September 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- Crowther, Bosley (18 December 1964). "Screen: 'Zorba, the Greek' Is at Sutton:Anthony Quinn Stars in Adaptation of Novel". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- Karalis, Vrasidas (2012). A History of Greek Cinema. Continuum. p. 98. ISBN 978-1441135001.

- Hunter, Jefferson (2013). "DVD Chronicle". The Hopkins Review. 6 (3): 408–416. doi:10.1353/thr.2013.0065. ISSN 1939-9774. S2CID 201770781.

- Elley, Derek (24 April 2001). "Review: 'Captain Corelli's Mandolin'". Variety. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Thomson, David (2010). The New Biographical Dictionary Of Film (5th ed.). Little, Brown. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-7481-0850-3.

- Ebert, Roger (13 July 1969). "Interview with Irene Papas". Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- "Spencer Tracy". Look. Vol. 26. 1962. p. 42.

long before production began, and asked 'Who is this broad Irene Papas?' Miss Papas was a Greek girl we had signed to star with him in the picture. He asked me about her height, and when I told him she was a big, rawboned 5 feet 10 inches, Tracy, who is about 5 feet 10, walked away.

- Giofkou, Daphne (2014). "[Review] 'Ancient Greek Women in Film', Konstantinos P. Nikoloutsos (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013". The Kelvingrove Review. University of Glasgow (13). Article 2.

- Stam, Robert (1984). "[Review] Erendira by Alain Queffelean, Ruy Guerra, Gabriel García Márquez". Cinéaste. 13 (4): 50–52. JSTOR 41692571.

- "Ferdinando Scianna - IRENE PAPAS". Magnum Photos. 1973. Archived from the original on 10 September 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- "Irene Pappas sings Mikis Theodorakis". Info-Greece. Archived from the original on 28 October 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- "Irene Pappas Sings Mikis Theodorakis". FM Records. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- Dome, Malcolm (27 January 2015). "Malcolm Dome looks back on the impact of Aphrodite's Child's mythic prog masterpiece". Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

The band's label, Mercury, were certainly left bemused. In fact, they were so horrified by the scope and challenge of the double album that they initially refused to release it. In particular, Papas' graphic orgasm during Infinity struck the wrong chord with them. Eventually, the company relented and agreed to put it out on their Vertigo imprint.

- Henshaw, Laurie (19 August 1972). "The Greeks have a word for it". Melody Maker. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Trunk, Jonny. "Vangelis & Irene Papas - Odoes [sic]". Record Collector magazine. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Vangelis and Irene Papas lyrics - Odes lyrics (English translation)". Lyrics of Music by Vangelis. Archived from the original on 29 June 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

(Greek) Lyrics: Irene Papas and Arianna Stassinopoulos.

- Trunk, Jonny (November 2007). "Vangelis & Irene Papas - Rapsodies". Record Collector magazine. Archived from the original on 1 October 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Irene Pappas Asks Boycott Of Greece's 'Fourth Reich'". The New York Times. 20 July 1967. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- "Irene Papas: Das Porträt" (in German). Neues Deutschland: Sozialistische Tageszeitung. 1 November 2001. Archived from the original on 8 September 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- Loutzaki, Irene (2001). "Folk Dance in Political Rhythms". Yearbook for Traditional Music. 33: 127–137. doi:10.2307/1519637. JSTOR 1519637. S2CID 156081242.

- Williams, Steven (7 July 2004). "Irene Papas Comes Forward About A Love Affair With The Late Marlon Brando". Contact Music. Archived from the original on 7 November 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- "Cloudy Sunday". NY Sephardic Film Festival. 2016. Archived from the original on 9 March 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Press Conference on the developments regarding the 'Anna-Maria' Foundation" Archived 8 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, greekroyalfamily.org, 28 August 2003.

- "Irene Papas: Her niece reveals all the truth about her state of health". Altsantiri. 9 July 2018. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- Sloan, Jane (2007). Reel Women: An International Directory of Contemporary Feature Films about Women. Scarecrow Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-4616-7082-7.

- Tzavalas, Trifon (2012). Greek Cinema Volume 1 100 Years of Film History 1900-2000 (PDF). Hellenic University Club of Southern California. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-938385-11-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

Irene Pappas received the Best Performance Award.

- "awards 1962". Thessaloniki Film Festival. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- "Awards for 1971". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on 16 March 2004. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- Nolfi, Joey (5 July 2017). "Annette Bening named Venice Film Festival jury president, ending 10-year male streak". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- "Awards at Hamptons Film Festival". The New York Times. 25 October 1993. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- "FLAIANO INTERNATIONAL AWARDS WINNERS 1993: Flaiano Awards of Theatre". Premi Flaiano. Archived from the original on 9 September 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

Honorary Award to career achievements: Irene Papas

- "Irene Papas Leone d' oro alla carriera". La Repubblica (in Italian). 20 February 2009. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

Noi italiani la ricordiamo ancora come la bella Penelope dell' Odissea tv (anno 1969): Irene Papas la grande attrice greca, riceve alle 18 il Leone d' oro alla carriera del Festival Internazionale del Teatro della Biennale di Venezia diretto da Maurizio Scaparro dedicato al Mediterraneo che si apre oggi. L' attrice interpreterà "Medea", nell' originale di Euripide e nella riscrittura di Corrado Alvaro.

- "Irene Papas" (in German). Who's Who. 2015. Archived from the original on 10 September 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- "Relocation of the Drama School to the "Irene Papas – Athens School" | National Theatre of Greece". Latsis Foundation. 2017. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- Papas, Irene (1968). Songs of Theodorakis (LP). RCA Victor (FPM-215 and FSP-215).

- Papas, Irene; Vangelis (2007). Odes (CD). Polydor (06025 1720633 5).

Vocals – Irene Papas

- "Irene Papas". Cinemagraphe. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Lancia, Enrico; Melelli, Fabio (2005). Le straniere del nostro cinema. Gremese Editore. pp. 122–123. ISBN 978-88-8440-350-6.

- Bosisio, Paolo (2000). "Ho pensato a voi scrivendo Gigliola--", Teresa Franchini, un'attrice per D'Annunzio. Bulzoni. p. 298. ISBN 978-88-8319-529-7.

- Ρούβας, Άγγελος; Σταθακοπουλος, Χρηστος (2005). Ελληνικος κινηματογραφος, 1905-1970 (in Greek). Ελληνικα Γραμματα. p. 203. ISBN 978-960-406-777-0.

- "Ecce Homo – I sopravvissuti". FilmTV.it. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- "N.P. Il Segreto (1970)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- "Sutjeska (Battle of Sutjeska)". Film Museum (Austria). Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "Blood Wedding". mubi. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- "Un' Ombra Nell'Ombra (1979)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- Anklewicz, Larry (2000). Guide to Jewish Films on Video. KTAV Publishing. p. 2002. ISBN 978-0-88125-605-5.

- Maltin, Leonard (2 September 2014). Leonard Maltin's 2015 Movie Guide. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 2300. ISBN 978-0-698-18361-2.

- The Film Journal, Volume 92, Issues 1-6. Pubsun Corporation. 1989. p. 6.

- Sloan, Jane (2007). Reel Women, An International Directory of Contemporary Feature Films about Women. Scarecrow Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-4616-7082-7.

- Maltin, Leonard (2014). Leonard Maltin's 2015 Movie Guide. Penguin. p. 1058. ISBN 978-0-698-18361-2.

- Benson, Sheila. "Movie Review , Stuck on an 'Island' With Thin Script". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 1 July 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

The island's permanent resident is Greek-born painter Marquise (Irene Papas), fierce, opinionated, life-embracing--the quintessential Papas character.

- "A Talking Picture". Variety. 4 September 2003. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

External links

- Irene Papas at IMDb

- Irene Papas at the Internet Broadway Database

- Irene Papas discography at Discogs

- Irène Papas regarding her work as an actress (video interview with context and transcript) from Europe of Cultures, 1 June 1980