Early Indian epigraphy

The earliest undisputed deciphered epigraphy found in the Indian subcontinent are the Edicts of Ashoka of the 3rd century BCE, in the Brahmi script.

If epigraphy of proto-writing is included, undeciphered markings with symbol systems that may or may not contain linguistic information, there is substantially older epigraphy in the Indus script, which dates back to the early 3rd millennium BCE. Two other important archeological classes of symbols are found from the 1st millennium BCE, Megalithic graffiti symbols and symbols on punch-marked coins, though most scholars do not consider these to constitute fully linguistic scripts, and their semiotic functions are not well understood.

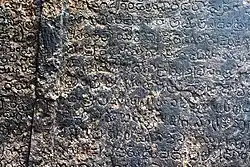

Writing in Sanskrit (Epigraphical Hybrid Sanskrit, EHS) appears in the 1st to 4th centuries CE.[4] Indian epigraphy becomes more widespread over the 1st millennium, engraved on the faces of cliffs, on pillars, on tablets of stone, drawn in caves and on rocks, some gouged into the bedrock. Later they were also inscribed on palm leaves, coins, Indian copper plate inscriptions, and on temple walls.

Many of the inscriptions are couched in extravagant language, but when the information gained from inscriptions can be corroborated with information from other sources such as still existing monuments or ruins, inscriptions provide insight into India's dynastic history that otherwise lacks contemporary historical records.[5]

Of the c. 100,000 inscriptions found by the Archaeological Survey of India, about 60,000 were in Tamil Nadu.[6]

First appearance of writing in the Indian Subcontinent

The Bronze Age Indus script remains undeciphered and may not actually represent a writing system. Hence, the first undisputed evidence of writing in the subcontinent are the Edicts of Ashoka from c. 250 BCE.[7] Several inscriptions were thought to be pre-Ashokan by earlier scholars; these include the Piprahwa relic casket inscription, the Badli pillar inscription, the Bhattiprolu relic casket inscription, the Sohgaura copper plate inscription, the Mahasthangarh Brahmi inscription, the Eran coin legend, the Taxila coin legends, and the inscription on the silver coins of Sophytes. However, more recent scholars have dated them to later periods.[8]

Until the 1990s, it was generally accepted that the Brahmi script used by Ashoka spread to South India during the second half of the 3rd century BCE, assuming a local form now known as Tamil-Brahmi. Beginning in the late 1990s, archaeological excavations have produced a small number of candidates for Brahmi epigraphy predating Ashoka. Preliminary press reports of such pre-Ashokan inscriptions have appeared over the years, such as Palani,[9][10] Erode,[11] and Adichanallur,[12] dated to c. 500 BCE, but so far only the claimed pre-Ashokan inscriptions at Anuradhapura have been published in an internationally recognised academic journal.[13]

History and research

Since 1886 there have been systematic attempts to collect and catalogue these inscriptions, along with the translation and publication of documents.[14] Inscriptions may be in the Brahmi or Tamil-Brahmi script. Royal inscriptions were also engraved on copper-plates as were the Indian copper plate inscriptions. The Edicts of Ashoka contain Brahmi script and its regional variant, Tamil-Brahmi, was an early script used in the inscriptions in cave walls of Tamil Nadu and later evolved into the Tamil Vatteluttu alphabet.[15] The Bhattiprolu alphabet, as well as a variant of Brahmi, the Kadamba alphabet, of the early centuries BCE gave rise to the Telugu-Kannada alphabet, which developed into the Kannada and Telugu scripts.

Notable inscriptions

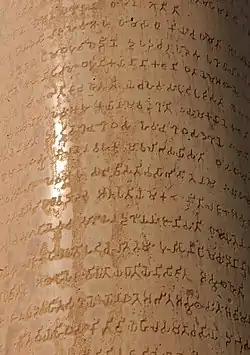

Important inscriptions include the 33 inscriptions of emperor Ashoka on the Pillars of Ashoka (272 to 231 BCE), the Sohgaura copper plate inscription (earliest known example of the copper plate type and generally assigned to the Mauryan period, though the exact date is uncertain),[16] the Hathigumpha inscription of Kharavela (2nd century BCE), the Besnagar pillar inscription of Heliodorus, the Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman I (150 CE), the Nasik cave inscriptions, the Rabatak inscription, the Allahabad Pillar inscription of Samudragupta, the Aihole inscription of Pulakesi II (634 CE), the Kannada Halmidi inscription, and the Tamil copper-plate inscriptions. The oldest known inscription in the Kannada language, referred to as the Halmidi inscription for the tiny village of Halmidi near where it was found, consists of sixteen lines carved on a sandstone pillar and dates to 450 CE.[17] Reports indicate that the Nishadi Inscription.[18] of Chandragiri which is in Old-Kannada is older than Halmidi by about 50 to 100 years and may belong to c. 350 CE or c. 400 CE.

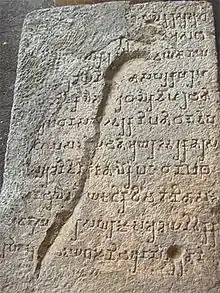

Hathigumpha inscription

The Hathigumpha inscription ("Elephant Cave" inscription) from Udayagiri near Bhubaneshwar in Orissa was written by Kharavela, the king of Kalinga in India during the 2nd century BCE. The Hathigumpha inscription consists of seventeen lines incised in deep cut Brahmi letters on the overhanging brow of a natural cavern called Hathigumpha on the southern side of the Udayagiri hill near Bhubaneswar in Orissa. It faces straight toward the rock Edicts of Asoka at Dhauli located about six miles away.

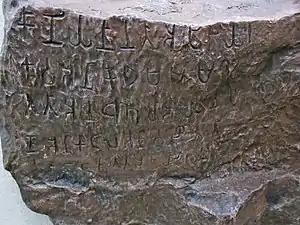

Rabatak inscription

The Rabatak inscription is written on a rock in the Bactrian language and Greek script and found in 1993 at the site of Rabatak, near Surkh Kotal in Afghanistan. The inscription relates to the rule of the Kushan emperor Kanishka and gives remarkable clues to the genealogy of the Kushan dynasty.

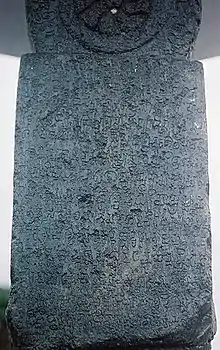

Halmidi inscription

The Halmidi inscription is the oldest known inscription in the Kannada language. The inscription is carved on a pillar, that was discovered in the village of Halmidi, a few miles from the famous temple town of Belur in the Hassan district of Karnataka, and is dated 450 CE. The original inscription has now been deposited in an archaeological museum in Bangalore while a fibreglass replica has been installed at Halmidi.

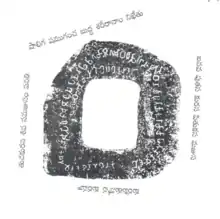

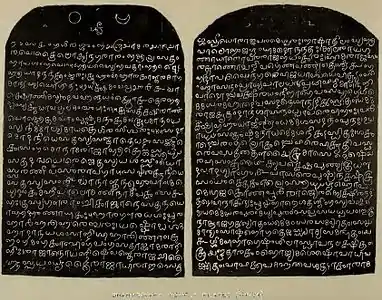

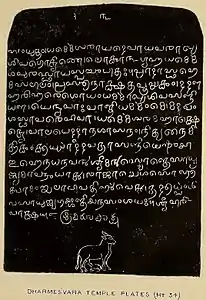

Tamil copper-plate inscriptions

Tamil copper-plate inscriptions are mostly records of grants of villages or plots of cultivable lands to private individuals or public institutions by the members of the various South Indian royal dynasties. The grants range in date from the 10th century CE to the mid-19th century CE. A large number of them belong to the Cholas and the Vijayanagara kings. These plates are valuable epigraphically as they give us an insight into the social conditions of medieval South India and help fill chronological gaps to connect the history of the ruling dynasties.

- Vijayanagara Tamil Copper Plate Inscriptions at the Dharmeshwara Temple, Kondarahalli, Hoskote

Plate 1 and Back

Plate 1 and Back Plate 2[19]

Plate 2[19]

Unlike the neighbouring states where early inscriptions were written in Sanskrit and Prakrit, the early inscriptions in Tamil Nadu used Tamil.[20] Tamil has the oldest extant literature amongst the Dravidian languages, but dating the language and the literature precisely is difficult. Literary works in India were preserved either in palm leaf manuscripts (implying repeated copying and recopying) or through oral transmission, making direct dating impossible.[21] However, external chronological records and internal linguistic evidence indicate that extant works were probably compiled sometime between the 4th century BCE and the 3rd century CE.[22][23][24] Epigraphic attestation of Tamil begins with rock inscriptions from the 3rd century BCE, written in Tamil-Brahmi, an adapted form of the Brahmi script.[25][26] The earliest extant literary text is the Tolkāppiyam, a work on poetics and grammar which describes the language of the classical period, dated variously between the 5th century BCE and the 2nd century CE.

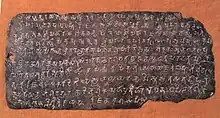

Shankarpur copper-plate of Budhagupta

The plate is a record documenting a donation in the reign of king Budhagupta (circa CE 477–88) in year 168 of the Gupta era. The date is equivalent to CE 487–88. The plate was found in Shankarpur, Sidhi District, Madhya Pradesh, India. The plate is currently stored in the Rani Durgawati Museum, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh. The copper plate is 24 cm x 11 cm. The inscription on the plate records that in the reign of Budhagupta, a ruler named mahārāja Gītavarman, grandson of mahārāja Vijayavarman and mahārāja Harivarman son of Rānī Svaminī and mahārāja Harivarman, donated a village named Citrapalli to a Gosvāmi brāhmaṇa. The text was written by Dūtaka Rūparāja(?), son of Nāgaśarma.

The inscription was published by B. C. Jain in 1977.[27] It was subsequently listed by Madan Mohan Upadhyaya in his book Inscriptions of Mahakoshal.[28]

The inscription is of considerable importance for the history of the Gupta Empire, because it is the last known record of the later Gupta king Budhagupta.[29] Moreover, it provides a secure date for Harivarman, the first recorded king of the Maukhari dynasty according to the Asīrgarh seal.[30]

siddham [||] samvatsara-ṣa(śa)te=ṣṭsa=ṣaṣṭyuta (yutta)re mahāmāgha-samvatsara(re) Śrāvaṇa ...

myāṃ paramadeva-Budhagupte rājani asyāṃ divasa-pūrvāyāṃ śrī-mahārāja-Sāṭana Sāla (or rya) na kul-odbhūtena śrī-mahārāja [Gī]tavarman-pautreṇa śrīmahārāja-Vijayavarmma-sute[na] mahādevyā[ṃ] Śarv asvāminyām utpanneana śri mahārāja Harivarmmaṇā asya brāhmaṇa-Kautsa- sagotra-gosvāmina [e]tac=Citrapalya tāmu(mra)paṭṭen=āgrahāro-tisṛṣṭaḥ akaraḥ acaṭa-bhaṭṭa-pra- veśyaḥ [|*] candra-tār-ārkka-samakālīyaḥ uktañca bhagavatā vyāsena [|*] svadattām= paradattāṃ=vā yo hareta vasundharā(rāṃ) [|*] s(ś)va vis(ṣ)ṭhāyā(yāṃ) kṛmir=bhūtvā pitṛbhis=saha majyate [||*] bahubhirv=vasudhā bhuktā rājabhiḥ=sagar-ādibhi (bhiḥ) [|*] yasya yasya yadā bhūmis=tasya tasya tadā phalaṃ [||*] kumārāmatya-bhagavad-rudrachadi-bhogika-mahāpratīhāra-lavaṇaḥ bapidra-bhogika (ke) [na]

dūtaka(ke)na likhitaṃ Śrī Yaṣṭarājena Nāga(sa)śarma-su[tena] [||*][31]

See also

- Related topics

- Ancient inscriptions Of Raju Rulers

- Ancient iron production

- Ashokan Edicts in Delhi

- Ashoka's Major Rock Edicts

- Dhar iron pillar

- History of metallurgy in the Indian subcontinent

- Iron pillar of Delhi

- Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman

- List of Edicts of Ashoka

- Pillars of Ashoka

- Stambha

- Tosham rock inscription

- Tamil inscriptions

- Other similar topics

Notes

- John D. Bengtson (2008). In Hot Pursuit of Language in Prehistory: Essays in the Four Fields of Anthropology : in Honor of Harold Crane Fleming. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 427–. ISBN 978-90-272-3252-6.

- R. Umamaheshwari (2018). Reading History with the Tamil Jainas: A Study on Identity, Memory and Marginalisation. Springer. p. 43. ISBN 978-81-322-3756-3.

- Hock, Hans Henrich; Bashir, Elena, eds. (24 May 2016). The Languages and Linguistics of South Asia: A Comprehensive Guide. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-042330-3.

- Salomon (1998), p. 81.

- Keay, John (2000). India: A History. New York: Grove Press. pp. xx–xxi. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

- Staff Reporter (22 November 2005). "Students get glimpse of heritage". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 18 May 2006. Retrieved 26 April 2007.

- Colin P. Masica, The Indo-Aryan Languages (Cambridge Language Surveys), Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Dilip K. Chakrabarty (2009). India: An Archaeological History: Palaeolithic Beginnings to Early Historic Foundations. Oxford University Press India. pp. 355–356. ISBN 978-0-19-908814-0.

- Kishore, Kavitha (15 October 2011). "Porunthal excavations prove existence of Indian scripts in 5th century BCE: expert". The Hindu. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- Porunthal excavations prove existence of Indian scripts in 5th century BCE: expert

- Subramaniam, T.S. (20 May 2013). "Kodumanal excavations prove existence of Indian scripts in 5th century BCE: expert". The Hindu. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- "Rudimentary Tamil-Brahmi script' unearthed at Adichanallur". The Hindu. 17 February 2005. Archived from the original on 12 October 2009.

- Coningham, R.A.E.; Allchin, F.R.; Batt, C.M.; Lucy, D. (1996), "Passage to India? Anuradhapura and the Early Use of the Brahmi Script", Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 6 (1): 73–97, doi:10.1017/S0959774300001608, S2CID 161465267

- "Indian inscriptions". Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- "Orality to literacy: Transition in Early Tamil Society". Frontline. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- Allchin, F.R. (1995). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities And States, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-37695-5, p.212

- "Halmidi village finally on the road to recognition". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 3 November 2003. Archived from the original on 24 November 2003. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- "Mysore scholar deciphers Chandragiri inscription". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 20 September 2008. Archived from the original on 22 September 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- Rice, Benjamin Lewis (1894). Epigraphia Carnatica: Volume IX: Inscriptions in the Bangalore District. Mysore State, British India: Mysore Department of Archaeology. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- Caldwell, Robert (1875). A comparative grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian family of languages. Trübner & co. p. 88.

In southern states, every inscription of an early date and majority even of modern day inscriptions were written in Sanskrit...In the Tamil country, on the contrary, all the inscriptions belonging to an early period are written in Tamil

. - Dating of Indian literature is largely based on relative dating relying on internal evidences with a few anchors. I. Mahadevan’s dating of Pukalur inscription proves some of the Sangam verses. See George L. Hart, "Poems of Ancient Tamil, University of Berkeley Press, 1975, p.7-8

- George Hart, "Some Related Literary Conventions in Tamil and Indo-Aryan and Their Significance" Journal of the American Oriental Society, 94:2 (Apr – Jun 1974), pp. 157-167.

- Kamil Veith Zvelebil, Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature, pp12

- Nilakanta Sastri, K.A. (1955). A History of South India, OUP, New Delhi (Reprinted 2002)

- "Tamil". The Language Materials Project. UCLA International Institute, UCLA. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- Iravatham Mahadevan (2003). Early Tamil Epigraphy from the Earliest Times to the Sixth Century A.D. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

- B. C. Jain, Journal of the Epigraphic Society of India 4 (1977): pp. 62-66 and plate facing p. 64.

- Madan Mohan Upadhyay, Inscriptions of Mahakoshal : Resource for the History of Central India (Delhi, 2005). ISBN 81-7646496-1. Online table of contents: http://indologica.blogg.de/2005/05/14/upadhyay-inscriptions-of-mahakoshal/ Archived 10 February 2013 at archive.today

- Michael D. Willis, "Later Gupta History: Inscriptions, Coins and Historical Ideology," Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland 15.2 (2005), p. 142. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/2057745/Later_Gupta_History_Inscriptions_Coins_and_Historical_Ideology.

- Michael D. Willis, "Later Gupta History: Inscriptions, Coins and Historical Ideology," Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland 15.2 (2005), p. 148. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/2057745/Later_Gupta_History_Inscriptions_Coins_and_Historical_Ideology.

- Shankarpur copper-plate of the time of Buddhagupta GE 168

References

- Salomon, Richard, Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the Other Indo-Aryan Languages, Oxford University Press, 1998,ISBN 978-0-19-509984-3

- Murugaiyan, Appasamy & Parlier-Renault, Édith (2021) (Eds) Whispering of Inscriptions: South Indian Epigraphy and Art History: Papers from an International Symposium in memory of Professor Noboru Karashima (Paris, 12–13 October 2017). Oxford: Indica et Buddhica. (2 vols) v. 1, ISBN 978-0-473-56774-3. v. 2, ISBN 978-0-473-56777-4. (Open access PDFs)

- Various (1988) [1988]. Amaresh Datta (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Indian literature – vol 2. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 81-260-1194-7.