Hyperinflation in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

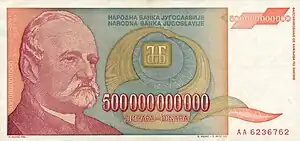

Between 1992 and 1994, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) experienced the second-longest period of hyperinflation in world economic history.[1] This period spanned 22 months, from March 1992 to January 1994. Inflation peaked at a monthly rate of 313 million percent in January 1994.[2] Daily inflation was 62%, with an inflation rate of 2.03% in 1 hour being higher than the annual inflation rate of many developed countries. The inflation rate in January 1994, converted to annual levels, reached 116,545,906,563,330 percent (116.546 trillion percent, or 1.16 × 1014 percent). During this period of hyperinflation in FR Yugoslavia, store prices were stated in conditional units – point, which was equal to the German mark. The conversion was made either in German marks or in dinars at the current "black market" exchange rate that often changed several times per day.[3]

The concept of inflation

The word "inflation" originates from the Latin word "inflare," meaning to blow or expand.[4] The word inflation, in the sense of inflating money circulation, was used for the first time in economic literature in the book, "The Big Paper Deception or the Approximation of a Financial Explosion" published by Alexander Demler[5] in New York in 1864. The book was published during the American Civil War where, due to four years of conflict between the North and the South, there was massive destruction and almost complete paralysis of the economy. Due to its inability to provide funds for financing military expenditures, the government resorted to issuing paper money without cover which caused rapid growth of prices and deterioration of the value of domestic currency.[6]

Since then, inflation has continued to be a frequently debated political topic and there exists extensive economic literature on the phenomenon. The reason for this lies in the fact that inflation is constantly present in contemporary economies and also because of the many controversial attitudes about inflation. There are severe disputes about its causes, manifestations, consequences, and measures for its removal. The classic concepts define inflation as a situation in which, due to an increase in money circulation, there is a decrease in the value of money, which in turn causes prices to increase. The reason for this is the fact that all of the large-scale inflation at that time was related to excessive money (paper money) emissions and that the huge monetary funds that were standing against the limited commodity funds were created on the market. In other words, a situation has arisen in which "too much money goes for too much quantity of goods."[7] Modern understandings point to the fact that inflation also occurs when this does not manifest itself in a general increase in prices. This is best seen in the former socialist countries in which there was a strong state price control. The prices remained stable but the shortcomings of certain commodities appeared on the market. However, any increase in monetary circulation and in free-market market economies does not automatically have to lead to a general increase in prices. This is inevitable only in a situation where we have a lot of capacity utilization and full employment of the labor force. On the other hand, a general increase in prices can also occur in cases when there is no increase in money circulation. This is due to distortions in the distribution of national income, the balance of payments and other segments where inflationary pressure arises which leads to a general increase in prices and without a rise in the money supply.

Stabilization program

Hyperinflation in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was managed with a heterodox stabilization program. At the beginning of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY), an orthodox program was applied instead. Both were relatively successful solutions in the short term, however they were not successful in the long term, which caused them to collapse.

Already at the beginning of 1994, another stabilization program under the name Monetary Reconstruction Program and Economic Recovery (known as the "Avramović Program") was in effect.

Program professor Dr. Dragoslav Avramović (Monetary Reconstruction and Economic Recovery Program) was adopted in early 1994 after a record hyperinflation that Yugoslavia had previously experienced. It was Yugoslavia in the period 1992–1994. It recorded the third-worst hyperinflation in world economic history, both by its duration of 22 months (March 1992 – January 1994), and at the maximum monthly level (January 1994) of 313,563,558 percent. Such devastating hyperinflation resulted in a drastic deterioration of all important economic indicators. 1993 saw a decline in GDP of 30%, a decrease in investments and industrial production of 37%, and unemployment reached 24.1%. At the same time, there was a huge budget deficit in a situation where public revenues were rapidly decreasing (the decline in tax base due to the decline in economic activity, and – due to sanctions – a significant increase in the "grey economy", which is why a large part of the so-called reduced social product remained untapped, etc.), and public expenditures increased significantly (because of increased social benefits due to deterioration of the economic situation in the country, economic and war support to the insurgent Serbian people in Bosnia and Croatia, the launching of the Bosnian and Croatian wars of independence, refugee assistance, etc.)

The budget deficit was largely financed from the primary issue, and this monetization of the budget deficit was the main cause of hyperinflation. Accordingly, the main measures of Avramović's program were primarily related to the monetary and fiscal sphere, and it can be concluded that this was an orthodox stabilization program. The stabilization program should, above all, accomplish:

– breaking the hyperinflation and returning the lost money function to the dinar,

– to enable fast and stable economic growth,

– a significant increase in wages (drastically depreciated during the period of hyperinflation) and ensuring the minimum safety of all citizens,

– essential reform of the economic system, especially in the financial sphere, and accelerating the transition process, etc.

At the same time, it was necessary to create conditions for the abolition of international sanctions as soon as possible and to open the economy abroad, without which the Program can not be fully implemented. Since it had become clear that the abolition of international economic sanctions could not wait, in order to join the breakdown of devastating hyperinflation, it was decided to start developing and implementing a stabilization program to be realized in two phases.[8]

The first, short-term phase envisaged monetary reconstruction and anti-inflationary measures aimed at breaking down hyperinflation. It was supposed to be realized in the first 6 months with its own forces, even under conditions of economic sanctions by the international community. The second, long-term phase envisioned essential economic reforms that (while preserving the stability achieved in the first phase) would lead to the economic recovery of the country, which would ensure long-term stable economic growth with an optimal employment rate and the growth of citizens' standards. This phase, as the authors of the Program have pointed out, assumed the abolition of economic sanctions and the flow of "fresh" capital needed for its realization. Since this assumption was not achieved, this second phase had no chance of significant success, as was the case with the first phase of the Program. Therefore, we will only detail the first stage of the Avramović program, because the implementation of the second phase did not occur, as international economic sanctions had not been abolished in the meantime. The first phase of the Monetary Reconstruction Program was realized under conditions of economic sanctions, without aid or any capital inflows, with initial foreign exchange reserves amounting to about 300 million German marks.[8]

It can be said that in the framework of the Monetary Reconstruction Program, the basic measures were focused on monetary policy, monetary reforms, and fiscal policy. Life in the country after the implementation of the stabilization program began to slowly return to normal. However, it is also important to point out that in these two years, thanks to the gray money issue, according to the estimates of economists from that period, 4.7 billion DEM from the citizens were bought.

The National Bank of Yugoslavia issued 33 banknotes during the stated hyperinflation period, of which 24 were issued in 1993. Yugoslav hyperinflation lasted for 24 months, which is longer than the German crisis after World War I, which lasted 16 months, the Greek crisis, which lasted 13 months, and the Hungarian crisis, which lasted 12 months.[8]

In popular culture

- A Diary of Insults (1994)

- The Wounds (1998)

- Three Palms for Two Punks and a Babe (1998)

- The Celts (2021)

References

- Hanke, Steve H. (2007-05-07). "The World's Greatest Unreported Hyperinflation". Cato Institute. Retrieved 2019-05-07 – via May 2007 issue of Globe Asia.

- Bogetic, Zeljko; Petrovic, Pavle; Vujosevic, Zorica (1999-02-01). "The Yugoslav Hyperinflation of 1992-1994: Causes, Dynamics, and Money Supply Process". Journal of Comparative Economics. 27 (2): 335–353. doi:10.1006/jcec.1999.1577. S2CID 153822874.

- "Yugoslavia: Montenegro Adopts German Mark As Currency -- But With Risks". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 2020-02-19.

- "inflo, inflas, inflare A, inflavi, inflatum - Latin is Simple Online Dictionary". www.latin-is-simple.com. Retrieved 2020-02-19.

- Leendertz, Ariane (2016), "Geschichte des Max-Planck-Instituts zur Erforschung der Lebensbedingungen der wissenschaftlich-technischen Welt in Starnberg (MPIL) und des Max-Planck-Instituts für Gesellschaftsforschung in Köln (MPIfG)", Handbuch Geschichte der deutschsprachigen Soziologie, Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, pp. 1–13, doi:10.1007/978-3-658-07998-7_58-1, ISBN 9783658079987

- "Inflation In The Confederacy". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- Burton, John (1972), "Theories of Inflation", Wage Inflation, Macmillan Education UK, pp. 15–20, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-01407-1_3, ISBN 9780333133422

- Petrović, Pavle; Bogetić, Željko; Vujošević, Zorica (1999). "The Yugoslav Hyperinflation of 1992–1994: Causes, Dynamics, and Money Supply Process" (PDF). Journal of Comparative Economics. 27 (2): 335–353. doi:10.1006/jcec.1999.1577. S2CID 153822874.

Further reading

- Allen, Larry (2009). The Encyclopedia of Money (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 227–228. ISBN 978-1598842517.