Hungary and the euro

While the Hungarian government has been planning since 2003 to replace the Hungarian forint with the euro, as of 2023, there is no target date and the forint is not part of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II). An economic study in 2008 found that the adoption of the euro would increase foreign investment in Hungary by 30%,[1] although current governor of the Hungarian National Bank and former Minister of the National Economy György Matolcsy said they did not want to give up the country's independence regarding corporate tax matters.[2]

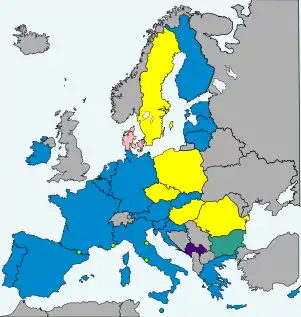

- European Union member states

-

5 not in ERM II, but obliged to join the eurozone on meeting the convergence criteria (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden)

- Non–EU member states

Adopting the euro

Under the MSZP governments between 2002 and 2010

Hungary originally planned to adopt the euro as its official currency in 2007 or 2008.[3] Later 1 January 2010 became the target date,[4][5] but that date was abandoned because of an excessively high budget deficit, inflation, and public debt. For years, Hungary could not meet any of the Maastricht criteria.[6] After the 2006 election, Prime Minister Ferenc Gyurcsány introduced austerity measures, causing protests in late 2006 and an economic slowdown in 2007 and 2008. However, in 2007, the deficit had been reduced to less than 5% (from 9.2%) and approached the 3% threshold in 2008. In 2008 analysts claimed that Hungary could join ERM II in 2010 or 2011 and so might adopt the euro in 2013, but more feasibly in 2014,[7] or later, depending on eurozone crisis developments. On 8 July 2008, the then Finance Minister János Veres announced the first draft of a euro-adoption plan.

After the 2008 global financial crisis, the likelihood of a fast adoption seemed greater.[8] Hungary received aid from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Union and the World Bank.[9] In October 2008 the head of Hungary's largest bank called for a special application to join the eurozone.[10]

Ferenc Gyurcsány ran out of political capital in March 2009 to accept necessary measures. The exchange rate reached 317 forints to one euro on 6 March. Gyurcsány initiated a constructive motion of no confidence against himself on 21 March and nominated Minister for Development and economist Gordon Bajnai as his replacement. The socialist and liberal parties accepted him as the new prime minister, with an interim government for one year from 14 April. Bajnai's premiership brought new austerity measures in Hungary. Thus, they may keep the deficit under 4% in 2009 and the 2010 Budget calculations assumed 3.8%. The inflation outturn was near 3% as a result of the crisis, but because of the increase in VAT, it averaged 5% in the second half of the year. Because of the IMF loan, the public debt rose to nearly 80%. The central bank interest rate fell to 6.25% from 10.5% in 2009. The Bajnai government could not lead Hungary into the ERM II, and it stated that it had no plans to do so.

Under the Fidesz government from 2010

The soft Eurosceptic Fidesz won enough seats in the 2010 Hungarian parliamentary election to form a government on its own. Fidesz was not specific then about its economic priorities. Shortly after the formation of the new government, they announced their intention to keep the 2010 deficit at 3.8%.[11] After more pressure, in September they also accepted a reduction to 3% in 2011.[12] In 2010, Finance Minister György Matolcsy said they would discuss euro adoption in 2012.[13] Mihály Varga, another member of the party, talked about possible euro adoption in 2014 or 2015.[14]

However, in February 2011, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán made clear that he does not expect the euro to be adopted in Hungary before 2020.[15] Later, Matolcsy also confirmed this statement. Orbán said the country was not yet ready to adopt the currency and they would not discuss the possibility until the public debt reached a 50% threshold.[16] The public debt-to-GDP ratio was 81.0% when Orbán's 50% target was set in 2011, and it is currently forecast to decline to 73.5% in 2016.[17]

In 2011, experts said that the earliest date that Hungary could adopt the euro was 2015.[18]

When the countries of the eurozone adopted the Euro-Plus Pact on 25 March 2011, Hungary decided to go along with the United Kingdom, Sweden and the Czech Republic and chose not to join the pact. Matolcsy said that they could agree with the most of its contents, but did not want to give up the country's independence regarding corporate tax matters.[2] As the Euro-Plus Pact does not feature any legal obligations - but only commitments to use various sets of voluntary tools to improve employment, competitiveness, fiscal responsibility and financial stability - joining this pact would not lead to a requirement for Hungary to abandon their current corporate tax method.

In April 2013, Viktor Orbán proclaimed euro adoption would not happen until the Hungarian purchasing power parity weighted GDP per capita had reached 90% of the eurozone average.[19] According to Eurostat, this relative percentage rose from 57.0% in 2004 to 63.4% in 2014.[20] If the same pace of "catching up" progress was to be expected in the future as in the past ten years (6.4% per decade), Hungary would only reach Orbán's 90% target and adopt the euro in 2056. Although, Hungary could potentially also reach Orbán's 90% target and adopt the euro in 2033, if being able for the upcoming period to sustain the same 1.4% of annual improvements in the figure as achieved from 2013 to 2014. Shortly after Orbán had been re-elected as Prime Minister for another four-year term in April 2014,[21] the Hungarian Central Bank announced that they planned to introduce a new series of forint banknotes in 2018.[22] In June 2015, Orbán declared that his government would no longer entertain the idea of replacing the forint with the euro in 2020, as was previously suggested, and instead expected the forint to remain "stable and strong for the next several decades",[23] although, in July 2016, National Economy Minister Mihály Varga suggested that country could adopt the euro by the "end of the decade", but only if economic trends continue to improve and the common currency becomes more stable.[24][25] No official target date has been set for euro adoption.

Public opinion

- Public support for the euro in Hungary[26]

The Maastricht criteria

Inflation

Inflation slowed down to 2.2% in 2006. However, after the austerity measures it was much higher than the criteria until the crisis. The crisis slowed it down to 2.9%, but in the end it was above the Maastricht criteria in 2009. The annual inflation was 0.9% in October 2013.

Budget deficit

The budget deficit was 9.2% in the election year of 2006. After the austerity measures, it neared the 3% threshold in 2008. The deficit was planned to be 3.9% in 2009, but was ultimately above 4%. The 2010 budget planned 3.8%, but it also went over 4%. Hungary's general government deficit, excluding the effect of one-off measures, was 2.43% of GDP in 2011, lower than the 2.94% target and under the 3% threshold for the first time since 2004. Hungary recorded a budget deficit of 1.9% in 2012, well below previous expectations. The budget deficit is expected to be under the 3% threshold in 2013 as well.[27]

Public debt

Public debt accounted for 80.1% of GDP in 2010,[28] above the 60% target. However, the EU might accept a Hungarian public debt which declines for at least 2 years.

Interest rate

The central bank's interest rate was raised by 3% to 11.5% in October 2008, because of the crisis. However, then it was lowered consecutively 14 times until 27 April 2010 down to 5.25%. Then it was raised 5 times until 21 December 2011 up to 7%. Since then the rate has declined 35 times, as of February 2019 the interest rate is 0.90%[29]

ERM-II membership

As the conservative government in 2013 did not plan to adopt the euro before 2020, there is no discussion about a possible ERM II membership.

Convergence status

| Assessment month | Country | HICP inflation rate[30][nb 1] | Excessive deficit procedure[31] | Exchange rate | Long-term interest rate[32][nb 2] | Compatibility of legislation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budget deficit to GDP[33] | Debt-to-GDP ratio[34] | ERM II member[35] | Change in rate[36][37][nb 3] | |||||

| 2012 ECB Report[nb 4] | Reference values | Max. 3.1%[nb 5] (as of 31 Mar 2012) |

None open (as of 31 March 2012) | Min. 2 years (as of 31 Mar 2012) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2011) |

Max. 5.80%[nb 7] (as of 31 Mar 2012) |

Yes[38][39] (as of 31 Mar 2012) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2011)[40] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2011)[40] | |||||||

| 4.3% | Open | No | -1.4% | 8.01% | No | |||

| -4.3% (surplus) | 80.6% | |||||||

| 2013 ECB Report[nb 8] | Reference values | Max. 2.7%[nb 9] (as of 30 Apr 2013) |

None open (as of 30 Apr 2013) | Min. 2 years (as of 30 Apr 2013) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2012) |

Max. 5.5%[nb 9] (as of 30 Apr 2013) |

Yes[41][42] (as of 30 Apr 2013) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2012)[43] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2012)[43] | |||||||

| 4.6% | Open (Closed in June 2013) | No | -3.5% | 6.97% | Unknown | |||

| 1.9% | 79.2% | |||||||

| 2014 ECB Report[nb 10] | Reference values | Max. 1.7%[nb 11] (as of 30 Apr 2014) |

None open (as of 30 Apr 2014) | Min. 2 years (as of 30 Apr 2014) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2013) |

Max. 6.2%[nb 12] (as of 30 Apr 2014) |

Yes[44][45] (as of 30 Apr 2014) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2013)[46] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2013)[46] | |||||||

| 1.0% | None | No | -2.6% | 5.80% | No | |||

| 2.2% | 79.2% | |||||||

| 2016 ECB Report[nb 13] | Reference values | Max. 0.7%[nb 14] (as of 30 Apr 2016) |

None open (as of 18 May 2016) | Min. 2 years (as of 18 May 2016) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2015) |

Max. 4.0%[nb 15] (as of 30 Apr 2016) |

Yes[47][48] (as of 18 May 2016) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2015)[49] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2015)[49] | |||||||

| 0.4% | None | No | -0.4% | 3.4% | No | |||

| 2.0% | 75.3% | |||||||

| 2018 ECB Report[nb 16] | Reference values | Max. 1.9%[nb 17] (as of 31 Mar 2018) |

None open (as of 3 May 2018) | Min. 2 years (as of 3 May 2018) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2017) |

Max. 3.2%[nb 18] (as of 31 Mar 2018) |

Yes[50][51] (as of 20 March 2018) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2017)[52] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2017)[52] | |||||||

| 2.2% | None | No | 0.7% | 2.7% | No | |||

| 2.0% | 73.6% | |||||||

| 2020 ECB Report[nb 19] | Reference values | Max. 1.8%[nb 20] (as of 31 Mar 2020) |

None open (as of 7 May 2020) | Min. 2 years (as of 7 May 2020) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2019) |

Max. 2.9%[nb 21] (as of 31 Mar 2020) |

Yes[53][54] (as of 24 March 2020) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2019)[55] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2019)[55] | |||||||

| 3.7% | None | No | -2.0% | 2.3% | No | |||

| 2.0% | 66.3% | |||||||

| 2022 ECB Report[nb 22] | Reference values | Max. 4.9%[nb 23] (as of April 2022) |

None open (as of 25 May 2022) | Min. 2 years (as of 25 May 2022) |

Max. ±15%[nb 6] (for 2021) |

Max. 2.6%[nb 23] (as of April 2022) |

Yes[56][57] (as of 25 March 2022) | |

| Max. 3.0% (Fiscal year 2021)[56] |

Max. 60% (Fiscal year 2021)[56] | |||||||

| 6.8% | None | No | -2.1% | 4.1% | No | |||

| 6.8% (exempt) | 76.8% (exempt) | |||||||

- Notes

- The rate of increase of the 12-month average HICP over the prior 12-month average must be no more than 1.5% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the similar HICP inflation rates in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these 3 states have a HICP rate significantly below the similarly averaged HICP rate for the eurozone (which according to ECB practice means more than 2% below), and if this low HICP rate has been primarily caused by exceptional circumstances (i.e. severe wage cuts or a strong recession), then such a state is not included in the calculation of the reference value and is replaced by the EU state with the fourth lowest HICP rate.

- The arithmetic average of the annual yield of 10-year government bonds as of the end of the past 12 months must be no more than 2.0% larger than the unweighted arithmetic average of the bond yields in the 3 EU member states with the lowest HICP inflation. If any of these states have bond yields which are significantly larger than the similarly averaged yield for the eurozone (which according to previous ECB reports means more than 2% above) and at the same time does not have complete funding access to financial markets (which is the case for as long as a government receives bailout funds), then such a state is not be included in the calculation of the reference value.

- The change in the annual average exchange rate against the euro.

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of May 2012.[38]

- Sweden, Ireland and Slovenia were the reference states.[38]

- The maximum allowed change in rate is ± 2.25% for Denmark.

- Sweden and Slovenia were the reference states, with Ireland excluded as an outlier.[38]

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2013.[41]

- Sweden, Latvia and Ireland were the reference states.[41]

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2014.[44]

- Latvia, Portugal and Ireland were the reference states, with Greece, Bulgaria and Cyprus excluded as outliers.[44]

- Latvia, Ireland and Portugal were the reference states.[44]

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2016.[47]

- Bulgaria, Slovenia and Spain were the reference states, with Cyprus and Romania excluded as outliers.[47]

- Slovenia, Spain and Bulgaria were the reference states.[47]

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of May 2018.[50]

- Cyprus, Ireland and Finland were the reference states.[50]

- Cyprus, Ireland and Finland were the reference states.[50]

- Reference values from the ECB convergence report of June 2020.[53]

- Portugal, Cyprus, and Italy were the reference states.[53]

- Portugal, Cyprus, and Italy were the reference states.[53]

- Reference values from the Convergence Report of June 2022.[56]

- France, Finland, and Greece were the reference states.[56]

References

- "About the impact of the EMU-entry". Science Direct. doi:10.1016/j.jimonfin.2007.12.005. S2CID 8884997. Archived from the original on 12 September 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Orbán: We will not join the Euro Pact.(In Hungarian.)". Hírszerző. Archived from the original on 25 March 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- "When will we have the euro?(In Hungarian.)". Origo. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- "MET – Magyarországi Európa Társaság – On the Introduction of the Euro in Hungary: Let's Stick to 2010!". Europatarsasag.hu. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- "Veres: Euro can come in 2010.(In Hungarian.)". Sulinet. Archived from the original on 14 February 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- "Slovak euro application approved.(In Hungarian.)". FigyelőNet. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- "Can we really have the euro first in the region?(In Hungarian.)". Menedzser Fórum. Archived from the original on 26 December 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- "Crisis can make faster euro adoption.(In Hungarian.)". KEMKIK. Archived from the original on 28 August 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- "Hungary to get $25.1 billion in IMF-led aid deal". The Economic Times. 29 October 2008. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- "Csányi: Euro adoption, anyway!(In Hungarian.)". FigyelőNet. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- "Matolcsy in Luxembourg: we will keep the deficit at 3,8%.(In Hungarian.)". Hírszerző. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- "Matolcsy: deficit will be under 3% in 2011.(In Hungarian.)". Index. 8 September 2010. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- "Hungary May Name Euro Entry Target Date in 2012, Matolcsy Says". Businessweek. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- "Varga promises euro in 2014 or 2015.(In Hungarian.)". GazdaságiRádió. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- "Orbán: We won't have euro until 2020" (in Hungarian). Index. 5 February 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- "Matolcsy: Hungarian euro is possible in 2020" (in Hungarian). Világgazdaság. 4 March 2011. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- "European Economic Forecast Spring 2015 - 17.Hungary" (PDF). European Commission. 5 May 2015.

- "Ungarn: Euro-Einführung noch nicht absehbar – Wirtschaft in Ungarn". Balaton-zeitung.info. 1 December 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- "Orbán: Hungary will keep forint until its GDP reaches 90% of eurozone average". All Hungary Media Group. 26 April 2013. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- "Purchasing power parities (PPPs), price level indices and real expenditures for ESA2010 aggregates: GDP Volume indices of real expenditure per capita in PPS (EU28=100)". Eurostat. 16 June 2015.

- "Hungary election: PM Viktor Orban declares victory". BBC. 6 April 2014.

- "Hungary's New Notes Speak of Late Conversion to Euro". The Wall Street Journal. 1 September 2014.

- "Orbán: Hungary will not adopt the euro for many decades to come". Hungarian Free Press. 3 June 2015.

- "HUNGARY'S ECONOMY MINISTER SEES POSSIBILITY FOR ADOPTING EURO BY 2020 – UPDATE". Daily News Hungary. 3 June 2015.

- "Hungary mulls euro adoption by 2020". BR-epaper. 19 July 2016.

- "Eurobarometer".

- "Portfolio.hu".

- "Hungarian public debt lowered and rose as well.(In Hungarian.)". Napi Gazdaság. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2011.

- "Hungarian National Bank Interest rate". Hungarian National Bank. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- "HICP (2005=100): Monthly data (12-month average rate of annual change)". Eurostat. 16 August 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- "The corrective arm/ Excessive Deficit Procedure". European Commission. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Long-term interest rate statistics for EU Member States (monthly data for the average of the past year)". Eurostat. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- "Government deficit/surplus data". Eurostat. 22 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- "General government gross debt (EDP concept), consolidated - annual data". Eurostat. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "ERM II – the EU's Exchange Rate Mechanism". European Commission. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Euro/ECU exchange rates - annual data (average)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Former euro area national currencies vs. euro/ECU - annual data (average)". Eurostat. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Convergence Report May 2012" (PDF). European Central Bank. May 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- "Convergence Report - 2012" (PDF). European Commission. March 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2012" (PDF). European Commission. 1 May 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- "Convergence Report - 2013" (PDF). European Commission. March 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2013" (PDF). European Commission. February 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Convergence Report - 2014" (PDF). European Commission. April 2014. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2014" (PDF). European Commission. March 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- "Convergence Report" (PDF). European Central Bank. June 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "Convergence Report - June 2016" (PDF). European Commission. June 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2016" (PDF). European Commission. May 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "Convergence Report 2018". European Central Bank. 22 May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Convergence Report - May 2018". European Commission. May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2018". European Commission. May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Convergence Report 2020" (PDF). European Central Bank. 1 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Convergence Report - June 2020". European Commission. June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "European economic forecast - spring 2020". European Commission. 6 May 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Convergence Report June 2022" (PDF). European Central Bank. 1 June 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "Convergence Report 2022" (PDF). European Commission. 1 June 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- "Luxembourg Report prepared in accordance with Article 126(3) of the Treaty" (PDF). European Commission. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2012.

- "EMI Annual Report 1994" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). April 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.

- "Progress towards convergence - November 1995 (report prepared in accordance with article 7 of the EMI statute)" (PDF). European Monetary Institute (EMI). November 1995. Retrieved 22 November 2012.