Horace King (architect)

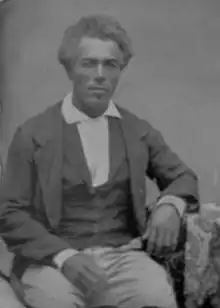

Horace King (sometimes Horace Godwin) (September 8, 1807 – May 28, 1885) was an African-American architect, engineer, and bridge builder.[1] King is considered the most respected bridge builder of the 19th century Deep South, constructing dozens of bridges in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi.[2] King was born into slavery on a South Carolina plantation in 1807. A slave trader sold him to a man who saw something special in Horace King. His owner, John Godwin taught King to read and write as well as how to build at a time when it was illegal to teach slaves. King worked hard and despite bondage, racial prejudice and a multitude of obstacles, King focused his life on working hard and being a genuinely good man. King built bridges, warehouses, homes, and churches. Horace King became a highly accomplished Master Builder and he emerged from the Civil War as a legislator in the State of Alabama. Affectionately known as Horace “The Bridge Builder” King and the "Prince of Bridge Builders," he also served his community in many important civic capacities."[3]

Horace King | |

|---|---|

Horace King during the mid-19th century | |

| Member of the Alabama House of Representatives | |

| In office 1868–1872 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 8, 1807 Chesterfield County, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | May 28, 1885 (aged 77) Lagrange, Georgia, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Occupation | Architect, engineer, contractor |

Early career

Horace King was born into slavery in 1807 in the Cheraw District of South Carolina, in present-day Chesterfield County. King's ancestry was a mix of African, European, and Catawba.[4] Mid-20th century biographer F. L. Cherry described his complexion as showing more "Indian blood than any other."[5] Taught to read and write at an early age, he had become a proficient carpenter and mechanic by his teenage years.[6]

Records indicate King spent his first 23 years near his birthplace, with his first introduction to bridge construction in 1824.[7] In 1824, bridge architect Ithiel Town came to Cheraw to assist in the construction of a bridge over the Pee Dee River. While it is unknown whether King assisted in the construction of this bridge or its replacement span built in 1828, Town's lattice truss design, used in both Pee Dee bridges, became a hallmark of King's future work.[8]

When King's master died around 1830, King was sold to John Godwin, a contractor who also worked on the Pee Dee bridge.[9] King may have been related to the family of Godwin's wife, Ann Wright.[4] In 1832, Godwin received a contract to construct a 560-foot (170 m) bridge across the Chattahoochee River from Columbus, Georgia to Girard, Alabama (today Phenix City). Initially living in Columbus, he moved to Girard in 1833, taking King with him.[10] The pair began many other construction projects, including house building. They built Godwin's house first, then King's. This was followed by many speculative houses, and the two men completed nearly every early house in Girard. The Columbus City Bridge was the first known to be built by King, who likely planned the construction of the bridge and managed the slave laborers who built the span.[11]

Rise to prominence

Between the completion of the Columbus City Bridge in 1833 and the early 1840s, King and Godwin partnered on no fewer than eight major construction projects throughout the South. The partners constructed some forty cotton warehouses in Apalachicola, Florida in 1834. Scholars believe that Godwin sent King in the mid-1830s for study at Oberlin College in Ohio, the first college in the United States to admit African-American students. The two men designed and built the courthouses of Muscogee County, Georgia and Russell County, Alabama from 1839 to 1841, and bridges in West Point, Georgia (1838), Eufaula, Alabama (1838–39), Florence, Georgia (1840). They built a replacement for their Columbus City Bridge between Columbus and Girard in 1841, as the original had been destroyed during an 1838 flood.[12]

During a time of financial difficulty, in 1837 Godwin transferred ownership of King to his wife and her uncle, William Carney Wright of Montgomery, Alabama. This may have been done to protect King from being taken and sold by Godwin's creditors.[4] King was allowed to marry Frances Gould Thomas, a free woman of color, in April 1839. It was extremely uncommon for slave owners to allow such marriages, since Frances' free status meant that their children would all be born free.[4] Slave states had incorporated the principle of partus sequitur ventrem into law since the colonial period, which said that children took the social status of their mothers, whether slave or free.

By 1840, King was being publicly acknowledged as being a "co-builder" along with Godwin, an uncommon honor for a slave.[13] King's prominence had eclipsed that of his master by the early 1840s. He worked independently as architect and superintendent of major bridge projects in Columbus, Mississippi (1843) and Wetumpka, Alabama (1844).[4][11] While working on the Eufaula bridge, King met Tuscaloosa attorney and entrepreneur Robert Jemison, Jr., who soon began using King on a number of different projects in Lowndes County, Mississippi, including the 420-foot (130 m) Columbus, Mississippi bridge. Jemison would remain King's friend and associate for the rest of his life.[14] King bridged the Tallapoosa River at Tallassee, Alabama in 1845. Later that same year he built three small bridges for Jemison near Steens, Mississippi, where the latter owned several mills.[4]

Freedom

Despite his enslavement, King was allowed to keep a significant income from his work. In 1846, he used some of his earnings to purchase his freedom from the Godwin family and Wright. But, under Alabama law of the time, a freed slave was allowed to remain in the state only for a year after manumission. Jemison, who served in the Alabama State Senate, arranged for the state legislature to pass a special law giving King his freedom and exempting him from the manumission law. In 1852, King used his freedom to purchase land near his former master.[15] When Godwin died in 1859, King had a monument erected over his grave.[4]

In 1849, the Alabama State Capitol burned, and King was hired to construct the framework of the new capitol building, as well as design and build the twin spiral entry staircases. King used his knowledge of bridge-building to cantilever the stairs' support beams so that the staircases appeared to "float," without any central support.[16]

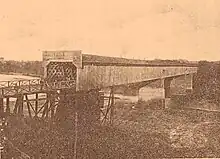

Around 1855, King formed a partnership with two other men to construct a bridge, known as Moore's Bridge, over the Chattahoochee between Newnan and Carrollton, Georgia, near Whitesburg. Instead of collecting a fee for his work, King took stock instead, gaining a one-third interest in the bridge. King moved his wife and children to the area near the bridge about 1858, although he continued to commute between it and their other home in Alabama. Frances King and their children collected the bridge tolls and farmed at Moore's Bridge.[4] The earnings from Moore's Bridge generated a steady income for King and his family. He also continued to design and construct major bridge projects through the remainder of the 1850s, including a major bridge in Milledgeville, Georgia and a second Chattahoochee crossing at Columbus, Georgia.[17]

As slaveholder

In the 1850s in Columbus, King purchased a slave who eventually became known as celebrated abolitionist J. Sella Martin. When King attempted to subdue Martin by flogging him, he was disappointed by the man's resistance. He quickly sold Martin to a slave trader.[18][19][20]

War times

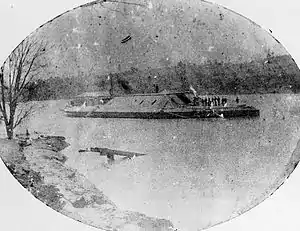

As the American Civil War approached in 1860, King, like many blacks in the South, opposed secession of the Southern states and was a confirmed Unionist. After the outbreak of hostilities, King attempted to continue his business as an architect and builder, constructing a factory and a mill in Coweta County, Georgia and a bridge in Columbus, Georgia. While working on the Columbus bridge, King was conscripted by Confederate authorities to build obstructions in the Apalachicola River, 200 miles (320 km) south of Columbus to prevent a naval attack on that city. After completing the obstructions on the Apalachicola, King was tasked to construct defenses on the Alabama River before returning to Columbus in 1863.[21]

By this time, Columbus had become a major shipbuilding city for the Confederacy. King and his men were assigned to assist construction of naval vessels at the Columbus Iron Works and Navy Yard. In 1863–64, King constructed a rolling mill for the Iron Works, which manufactured cladding for Confederate ironclad warships. King's crews also provided lumber and timbers for the Navy Yard. They were at least peripherally involved with the construction of the CSS Muscogee.[22] During 1864 King wrote to Jemison, who had also opposed secession but was then serving in the Confederate Senate. He asked what would be likely to happen if he stopped his work for the Confederacy. Jemison's response is unknown.[4]

As the war approached its end in 1864, many of King's bridges were destroyed by Union troops. This included Moore's Bridge, which King owned. Moore's Bridge was destroyed by Union cavalry in July 1864. Frances King died on October 1, 1864, at Girard, leaving King a widower with five surviving children to care for. Raiders under Union general James H. Wilson assaulted Columbus in April 1865, burning all of King's bridges in that city, including the one he had finished less than two years earlier.[23] King remarried in June 1865 to Sarah Jane Jones McManus.[4]

King and Reconstruction

The postwar period resulted in new opportunities for King. Within six months after the war's end, King and a partner had constructed a 32,000-square-foot (3,000 m2) cotton warehouse in Columbus, and King had—for the third time—rebuilt the original Columbus City Bridge. Over the next three years, King would construct three more bridges across the Chattahoochee: in Columbus, and two at West Point, Georgia, plus two large factories, and the Lee County, Alabama courthouse.[24]

When the Reconstruction Acts were implemented in 1867, King became a registrar for voters in Russell County, Alabama. Later that year, he attempted to establish a colony of freedmen in Georgia. While that plan was unsuccessful, King was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives in 1868 as a Republican representing Russell County. Busy in his construction business in Columbus, King did not take his seat for more than a year, in November 1869. King remained a reluctant legislator, voting 78% of the time and proposing only three bills—none of which became law. King was reelected in 1870, proposing no bills in the 1870-71 session and only five in the 1871-72 session, one of which—a prohibition on the sale of alcohol in Hurtsboro, Alabama—became law. King did not seek reelection in 1872.[25]

Final years

King left the Alabama Legislature in 1872 and moved with his family to LaGrange, Georgia. While in LaGrange, King continued building bridges, but also expanded to include other construction projects, specifically businesses and schools. By the mid-1870s, King had begun to pass on his bridge construction activities to his five children, who formed the King Brothers Bridge Company. King's health began failing in the 1880s, and he died on May 28, 1885, in LaGrange.[26]

King received laudatory obituaries in each of Georgia's major newspapers, a rarity for African Americans in the 1880s South. He was posthumously inducted into the Alabama Engineers Hall of Fame at the University of Alabama. The award was accepted on his behalf by his great-grandson, Horace H. King, Jr.[27] He was remembered both for his engineering skill and for his character.[28]

Works

- Columbus, Georgia Bridge (Destroyed by a flood in 1841). (1832–33)

- Forty cotton warehouses in Apalachicola, Florida. (1834)

- West Point, Georgia Bridge. (1838)

- Eufaula, Alabama Bridge (Demolished in 1924). (1838–39)

- Florence, Georgia Bridge. (1840)

- Replacement Columbus, Georgia Bridge. (1841)

- Muscogee County Courthouse. (1839–41)

- Russell County Courthouse. (1839–41)

- Red Oak Creek Covered Bridge, Georgia. listed on the National Register of Historic places and is the last remaining covered bridge designed by King. (1840s)

- Second Columbus, Mississippi Bridge (Burned during American Civil War). (1843)

- Wetumpka, Alabama Bridge. (1844)

- Tallassee, Alabama Bridge. (1845)

- 3 minor bridges near Steens, Mississippi. (1845)

- Interior framework and spiral staircases of the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery, Alabama, listed on the National Register of Historic Places and as a National Historic Landmark. (1850–51)

- Moore's Bridge near Whitesburg, Georgia (Burned during Civil War). (1855)

- Milledgeville, Georgia Bridge. (1850s)

- The Bridge House (Albany, Georgia) in Albany, Georgia, listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is now being used as the Albany Welcome Center. (1858)

- Third Columbus, Mississippi Bridge (Demolished 20th century). (1865)

- Tuscaloosa, Alabama Bridge over the Black Warrior River (destroyed by tornado in 1880). (1872)

See also

- F.L. Cherry, "The History of Opelika and Her Agricultural Tributary Territory," The Alabama Historical Quarterly 15, No. 2 (1953), Chapter V.

- J. David Dameron, Horace King: From Slave to Master Builder and Legislator, Southeast Research Publishing, LLC, 2017.

- John S. Lupold and Thomas L. French, Bridging Deep South Rivers: The Life and Legend of Horace King (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2004), ISBN 0-8203-2626-7.

- HORACE: The Bridge Builder King (Documentary), Produced by Tom C. Lenard. Part I on YouTube Part II on YouTube Part III on YouTube Part IV on YouTube Part V on YouTube Part VI on YouTube.

References

- Carl Vinson Institute of Government, University of Georgia , Horace King Historical Marker Archived September 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved November 3, 2007.

- The New Georgia Encyclopedia, "Horace King (1807-1885)", retrieved November 3, 2007.

- J. David Dameron, Horace King: From Slave to Master Builder and Legislator, Southeast Research Publishing, LLC, 2017.

- "Horace King". The Encyclopedia of Alabama. Auburn University. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- F.L. Cherry, "The History of Opelika and Her Agricultural Tributary Territory", The Alabama Historical Quarterly 15, No. 2 (1953), pp. 193, 197.

- Richard G. Weingardt (October 2007). "Horace King: From Slave to Master Bridge Builder" (PDF). Structure Magazine. National Council of Structural Engineers Associations. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- Lupold and French, Deep South Rivers, 14, 20.

- Lupold and French, Deep South Rivers, 20

- Cherry, History of Opelika, 197; Lupold and French, Bridging Deep South Rivers, 20.

- Lupold and French, Bridging Deep South Rivers, 51.

- The New Georgia Encyclopedia,"Horace King (1807-1885)".

- Lupold and French, Bridging Deep South Rivers, 83-84; Cherry, History of Opelika, 194.

- Lupold and French, Deep South Rivers, 83.

- Lupold and French, Deep South Rivers, 100, 121.

- Lupold and French, Deep South Rivers, 123-130.

- Lupold and French, Deep South Rivers, 134-135.

- Lupold and French, Deep South Rivers, 143-150.

- Noel, Baptist Wriothesley (1863). Freedom and Slavery in the United States of America. London: J. Nisbet. p. 162.

- Schweninger, Loren (November 1987). "Review: Beating against the Barriers: Biographical Essays in Nineteenth-Century Afro-American History. by R. J. M. Blackett". The Journal of Southern History. 53 (4): 659–660. doi:10.2307/2208789. JSTOR 2208789.

- Dave Gillarm (Executive Director of the Black History Museum of Columbus), quoted by Alva James-Johnson, "Local lynchings discussed at Columbus Tech," Columbus Ledger-Enquirer, February 23, 2016 (page 4).

- Lupold and French, Deep South Rivers, 163-167.

- Lupold and French, Deep South Rivers, 167-169.

- Lupold and French, Deep South Rivers, 174-175, 178-181.

- Lupold and French, Deep South Rivers, 182-195, 210.

- Lupold and French, Deep South Rivers, 211-221.

- Lupold and French, Deep South Rivers, 223-239.

- "HORACE: The Bridge Builder King" Part VI on YouTube

- Lupold and French, Deep South Rivers, 239-240; Horace King (1807-1888) Georgia's Master Bridge Builder Archived February 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved November 4, 2007.