Religious war

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war (Latin: sanctum bellum), is a war which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion and beliefs. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the extent to which religious, economic, ethnic or other aspects of a conflict are predominant in a given war. The degree to which a war may be considered religious depends on many underlying questions, such as the definition of religion, the definition of 'religious war' (taking religious traditions on violence such as 'holy war' into account), and the applicability of religion to war as opposed to other possible factors. Answers to these questions heavily influence conclusions on how prevalent religious wars have been as opposed to other types of wars.

| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

According to scholars such as Jeffrey Burton Russell, conflicts may not be rooted strictly in religion and instead may be a cover for the underlying secular power, ethnic, social, political, and economic reasons for conflict.[1] Other scholars have argued that what is termed "religious wars" is a largely "Western dichotomy" and a modern invention from the past few centuries, arguing that all wars that are classed as "religious" have secular (economic or political) ramifications.[2][3][4] In several conflicts including the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, the Syrian civil war, and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, religious elements are overtly present, but variously described as fundamentalism or religious extremism—depending upon the observer's sympathies. However, studies on these cases often conclude that ethnic animosities drive much of the conflicts.[5]

According to the Encyclopedia of Wars, out of all 1,763 known/recorded historical conflicts, 121, or 6.87%, had religion as their primary cause.[6] Matthew White's The Great Big Book of Horrible Things gives religion as the primary cause of 11 of the world's 100 deadliest atrocities.[7][8]

Definitions

Konrad Repgen (1987) pointed out that belligerents may have multiple intentions to wage a war, may have had ulterior motives that historians can no longer discover, and therefore, calling something a 'religious war' (or 'war of succession') based merely on a motive that a belligerent may have had, doesn't necessarily make it one.[9] Although ulterior motives may never be known, war proclamations do provide evidence for a belligerent's legitimisation of the war to the public.[9] Repgen therefore concluded:

...wars should only be termed [religious wars], in so far as at least one of the belligerents lays claim to 'religion', a religious law, in order to justify his warfare and to substantiate publicly why his use of military force against a political authority should be a bellum iustum.[9]

Philip Benedict (2006) argued that Repgen's definition of 'religious war' was too narrow, because sometimes both legitimisation and motivation can be established.[9] David Onnekink (2013) added that a 'religious war' is not necessarily the same as a 'holy war' (bellum sacrum): 'After all, it is perfectly acceptable to suggest that a worldly prince, say, a Lutheran prince in Reformation Germany, engages in religious warfare using mercenary armies.'[9] While a holy war needs to be authorised by a religious leader and fought by pious soldiers, a religious war does not, he reasoned.[9] His definition of 'war of religion' thus became:

a war legitimised by religion and/or for religious ends (but possibly fought by secular leaders and soldiers).[9]

Applicability of religion to war

Some commentators have questioned the applicability of religion to war, in part because the word "religion" itself is difficult to define, particularly posing challenges when one tries to apply it to non-Western cultures. Secondly, it has been argued that religion is difficult to isolate as a factor, and is often just one of many factors driving a war. For example, many armed conflicts may be simultaneously wars of succession as well as wars of religion when two rival claimants to a throne also represent opposing religions.[10] Examples include the War of the Three Henrys and the Succession of Henry IV of France during the French Wars of Religion, the Hessian War and the War of the Jülich Succession during the Reformation in Germany, and the Jacobite risings (including the Williamite–Jacobite wars) during the Reformation in Great Britain and Ireland.

John Morreall and Tamara Sonn (2013) have argued that since there is no consensus on definitions of "religion" among scholars and no way to isolate "religion" from the rest of the more likely motivational dimensions (social, political, and economic); it is incorrect to label any violent event as "religious".[11]

Theologian William T. Cavanaugh in his Myth of Religious Violence (2009) argues that the very concept of "religion" is a modern Western concept that was invented recently in history. As such, he argues that the concept of "religious violence" or "religious wars" are incorrectly used to anachronistically label people and conflicts as participants in religious ideologies that never existed in the first place.[2] The concept of "religion" as an abstraction which entails distinct sets of beliefs or doctrines is a recently invented concept in the English language since such usage began with texts from the 17th century due to the splitting of Christendom during the Protestant Reformation and more prevalent colonization or globalization in the age of exploration which involved contact with numerous foreign and indigenous cultures with non-European languages.[12] It was in the 17th century that the concept of "religion" received its modern shape despite the fact that the Bible, the Quran, and other ancient sacred texts did not have a concept of religion in the original languages and neither did the people or the cultures in which these sacred texts were written.[13] The modern word religion comes from the Latin word religio which, in the ancient and medieval world, was understood as an individual virtue of worship, never as doctrine, practice, or actual source of knowledge.[12] Cavanaugh argued that all wars that are classed as "religious" have secular (economic or political) ramifications.[2] Similar opinions were expressed as early as the 1760s, during the Seven Years' War, widely recognized to be "religious" in motivation, noting that the warring factions were not necessarily split along confessional lines as much as along secular interests.[4]

There is no precise equivalent of "religion" in Hebrew, and Judaism does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities.[14] In the Quran, the Arabic word deen is often translated as "religion" in modern translations, but up to the mid-17th century, translators expressed deen as "law".[13]

It was in the 19th century that the terms "Buddhism", "Hinduism", "Taoism", and "Confucianism" first emerged.[12][15] Throughout its long history, Japan had no concept of "religion" since there was no corresponding Japanese word, nor anything close to its meaning, but when American warships appeared off the coast of Japan in 1853 and forced the Japanese government to sign treaties demanding, among other things, freedom of religion, the country had to contend with this Western idea.[15] According to the philologist Max Müller, what is called ancient religion today, would have only been understood as "law" by the people in the ancient world.[16] In Sanskrit word dharma, sometimes translated as "religion", also means law. Throughout the classical Indian subcontinent, the study of law consisted of concepts such as penance through piety and ceremonial as well as practical traditions. Medieval Japan at first had a similar union between "imperial law" and universal or "Buddha law", but these later became independent sources of power.[17][18]

According to McGarry & O'Leary (1995), it is evident that religion as one aspect of a people's cultural heritage may serve as a cultural marker or ideological rationalization for a conflict that has deeper ethnic and cultural differences. They argued this specifically in the case of The Troubles in Northern Ireland, often portrayed as a religious conflict of a Catholic vs. a Protestant faction, while the more fundamental cause of the conflict was supposedly ethnic or nationalistic rather than religious in nature.[19] Since the native Irish were mostly Catholic and the later British-sponsored immigrants were mainly Protestant, the terms become shorthand for the two cultures, but McGarry & O'Leary argued that it would be inaccurate to describe the conflict as a religious one.[19]

In their 2015 review of violence and peacemaking in world religions, Irfan Omar and Michael Duffey stated: "This book does not ignore violence committed in the name of religion. Analyses of case studies of seeming religious violence often conclude that ethnic animosities strongly drive violence."[5]

Prevalence

The definition of 'religious war' and the applicability of religion to war have a strong influence on how many wars may be properly labelled 'religious wars', and thus how prevalent religious wars have been as opposed to other wars.

According to Kalevi Holsti (1991, p. 308, Table 12.2), who catalogued and categorised wars from 1648 to 1989 into 24 categories of 'issues that generated wars', 'protect[ion of] religious confrères' (co-religionists) was (one of) the primary cause(s) of 14% of all wars during 1648–1714, 11% during 1715–1814, 10% during 1815–1914, and 0% during 1918–1941 and 1945–1989.[20] Additionally, he found 'ethnic/religious unification/irredenta' to be (one of) the primary cause(s) of 0% of all wars during 1648–1714 and 1715–1814, 6% during 1815–1914, 17% during 1918–1941, and 12% during 1945–1989.[20]

In their 1997 Encyclopedia of Wars, authors Charles Phillips and Alan Axelrod documented 1763 notable wars in world history, out of which 121 wars were in the "religious wars" category in the index.[21][6] They note that before the 17th century, much of the "reasons" for conflicts were explained through the lens of religion and that after that time wars were explained through the lens of wars as a way to further sovereign interests.[22] Some commentators have concluded that only 123 wars (7%) out of these 1763 wars were fundamentally originated by religious motivations.[23][24][25] Andrew Holt (2018) traced the origin of the 'only 123 religious wars' claim back to the 2008 book The Irrational Atheist of far-right activist Vox Day, which he notes is slightly adjusted compared to the 121 that is indeed found in the Encyclopedia of Wars itself.[21]

The Encyclopedia of War, edited by Gordon Martel, using the criteria that the armed conflict must involve some overt religious action, concludes that 6% of the wars listed in their encyclopedia can be labelled religious wars.[26]

Holy war concepts in religious traditions

While early empires could be described as henotheistic, i.e. dominated by a single god of the ruling elite (as Marduk in the Babylonian empire, Assur in the Assyrian empire, etc.), or more directly by deifying the ruler in an imperial cult, the concept of "holy war" enters a new phase with the development of monotheism.[27]

Ancient warfare and polytheism

During classical antiquity, the Greco-Roman world had a pantheon with particular attributes and interest areas. Ares personified war. While he received occasional sacrifice from armies going to war, there was only a very limited "cult of Ares".[28] In Sparta, however, each company of youths sacrificed to Enyalios before engaging in ritual fighting at the Phoebaeum.[29]

Hans M. Barstad (2008) claimed that this ancient Greek attitude to war and religion differed from that of ancient Israel and Judah: 'Quite unlike what we find with the Greeks, holy war permeated ancient Israelite society.'[30] Moreover, ever since the pioneering study of Manfred Weippert, "»Heiliger Krieg« in Israel und Assyrien" (1972), scholars have been comparing the holy war concept in the (monotheistic) Hebrew Bible with other (polytheistic) ancient Near Eastern war traditions, and found 'many [striking] similarities in phraseology and ideology'.[30]

Christianity

According to historian Edward Peters, before the 11th century, Christians had not developed a concept of holy war (bellum sacrum), whereby fighting itself might be considered a penitential and spiritually meritorious act.[31][32] During the ninth and tenth centuries, multiple invasions occurred which led some regions to make their own armies to defend themselves and this slowly lead to the emergence of the Crusades, the concept of "holy war", and terminology such as "enemies of God" in the 11th century.[31][32] In early Christianity, St. Augustine's concept of just war (bellum iustum) was widely accepted, but warfare was not regarded as a virtuous activity[31][33] and expressions of concern for the salvation of those who killed enemies in battle, regardless of the cause for which they fought, was common.[31]

During the era of the Crusades, some of the Crusaders who fought in the name of God were recognized as the Milites Christi, the soldiers or the knights of Christ.[34] The Crusades were a series of military campaigns against the Muslim Conquests that were waged from the end of the 11th century through the 13th century. Originally, the goal of the Crusaders was the recapture of Jerusalem and the Holy Land from the Muslims, and the provision of support to the besieged Christian Byzantine Empire which was waging a war against Muslim Seljuq expansion into Asia Minor and Europe proper. Later, Crusades were launched against other targets, either for religious reasons, such as the Albigensian Crusade, the Northern Crusades, or because of political conflicts, such as the Aragonese Crusade. In 1095, at the Council of Clermont, Pope Urban II raised the level of the war from a bellum iustum (a "just war"), to a bellum sacrum (a "holy war").[35]

Hinduism

In the Hindu texts, dharma-yuddha refers to a war that is fought while following several rules that make the war fair.[36] In other words, just conduct within a war (jus in bello) is important in Vedic and epic literature such as the Mahabharata and the Ramayana.[37] However, according to Torkel Berkke, the Mahabharata does not provide a clear discussion on who has the authority to initiate a war (jus ad bellum), nor on what makes a war just (bellum justum).[37]

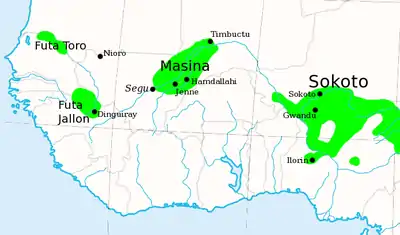

Islam

The Muslim conquests were a military expansion on an unprecedented scale, beginning in the lifetime of Muhammad and spanning the centuries, down to the Ottoman wars in Europe. Until the 13th century, the Muslim conquests were those of a more or less coherent empire, the Caliphate, but after the Mongol invasions, expansion continued on all fronts (other than Iberia which was lost in the Reconquista) for another half millennium until the final collapse of the Mughal Empire in the east and the Ottoman Empire in the west with the onset of the modern period.

There were also a number of periods of infighting among Muslims; these are known by the term Fitna and mostly concern the early period of Islam, from the 7th to 11th centuries, i.e. before the collapse of the Caliphate and the emergence of the various later Islamic empires.

While technically, the millennium of Muslim conquests could be classified as "religious war", the applicability of the term has been questioned. The reason is that the very notion of a "religious war" as opposed to a "secular war" is the result of the Western concept of the separation of Church and State. No such division has ever existed in the Islamic world, and consequently, there cannot be a real division between wars that are "religious" from such that are "non-religious". Islam does not have any normative tradition of pacifism, and warfare has been integral part of Islamic history both for the defense and the spread of the faith since the time of Muhammad. This was formalised in the juristic definition of war in Islam, which continues to hold normative power in contemporary Islam, inextricably linking political and religious justification of war.[38] This normative concept is known as Jihad, an Arabic word with the meaning "to strive; to struggle" (viz. "in the way of God"), which includes the aspect of struggle "by the sword".[39]

The first forms of military jihad occurred after the migration (hijra) of Muhammad and his small group of followers to Medina from Mecca and the conversion of several inhabitants of the city to Islam. The first revelation concerning the struggle against the Meccans was Quran 22:39-40:[40]

Permission ˹to fight back˺ is ˹hereby˺ granted to those being fought, for they have been wronged. And Allah is truly Most Capable of helping them ˹prevail˺. ˹They are˺ those who have been expelled from their homes for no reason other than proclaiming: “Our Lord is Allah.” Had Allah not repelled ˹the aggression of˺ some people by means of others, destruction would have surely claimed monasteries, churches, synagogues, and mosques in which Allah’s Name is often mentioned. Allah will certainly help those who stand up for Him. Allah is truly All-Powerful, Almighty.

This happened many times throughout history, beginning with Muhammad's battles against the polytheist Arabs including the Battle of Badr (624), and battles in Uhud (625), Khandaq (627), Mecca (630) and Hunayn (630).

Judaism

Reuven Firestone (2012) stated 'that holy war is a common theme in the Hebrew Bible. Divinely legitimized through the authority of biblical scripture and its interpretation, holy war became a historical reality for the Jews of antiquity. Among at least some of the Jewish groups of the late Second Temple period until the middle of the second century, C.E., holy war was an operative institution. That is, Jews engaged in what is defined here as holy war.'[41] He mentioned the Maccabean Revolt (167–160 BCE), the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE) and the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 CE) as three examples of a "holy war" or "Commanded War" (Hebrew: מלחמת מצווה Milkhemet Mitzvah) in the eyes of Rabbinic Judaism at the time.[41] He asserted that this concept may have re-emerged in modern times within some factions of the Zionist movement, particularly Revisionist Zionism.[42]

In 2016, however, Firestone made a distinction between what he regarded as the Hebrew Bible's concept and the 'Western' concept of holy war: ""Holy war" is a Western concept referring to war that is fought for religion, against adherents of other religions, often in order to promote religion through conversion, and with no specific geographic limitation. This concept does not occur in the Hebrew Bible, whose wars are not fought for religion or in order to promote it but, rather, in order to preserve religion and a religiously unique people in relation to a specific and limited geography."[43]

Several scholars regard war narratives in the Hebrew Bible, such as the war against the Midianites in Numbers 31, to be a holy war, with Niditch (1995) asserting the presence of a 'priestly ideology of war in Numbers 31'.[44] Hamilton (2005) argued that the two major concerns of Number 31 are the idea that war is a defiling activity, but Israelite soldiers need to be ritually pure, so they may only fight wars for a holy cause, and are required to cleanse themselves afterwards to restore their ritual purity.[45] The Israelite campaign against Midian was blessed by the Israelite god Yahweh, and could therefore be considered a holy war.[45] Olson (2012), who believed the war narrative to be a fictional story with a theological purpose, noted that the Israelite soldiers' actions in Numbers 31 closely followed the holy war regulations set out in Deuteronomy 20:14, although Moses' commandment to also kill the captive male children and non-virgin women was a marked departure from these regulations.[46] He concluded: "Many aspects of this holy war text may be troublesome to a contemporary reader. But understood within the symbolic world of the ancient writers of Numbers, the story of the war against the Midianites is a kind of dress rehearsal that builds confidence and hope in anticipation of the actual conquest of Canaan that lay ahead."[46]

Dawn (2016, translating Rad 1958) stated: "From the earliest days of Israel's existence as a people, holy war was a sacred institution, undertaken as a cultic act of a religious community".[47]

Shinto

Sikhism

Antiquity

In Greek antiquity, four (or five) wars were fought in and around the Panhellenic sanctuary at Delphi (the Pythia (Oracle) residing in the Temple of Apollo) against persons or states who allegedly committed sacrilegious acts before the god Apollo.[53] The following are distinguished:

- The First Sacred War (595–585 BCE)

- The Second Sacred War (449–448 BCE)

- The Third Sacred War (356–346 BCE)

- The Fourth Sacred War (339–338 BCE)

- The Fifth Sacred War (281–280 BCE)

Firestone (2012) stated that in the eyes of ancient Rabbinic Judaism, the Maccabean Revolt (167–160 BCE), the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE) and the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 CE) were "holy wars" or "Commanded Wars" (Hebrew: מלחמת מצווה Milkhemet Mitzvah).[41]

Middle Ages

Christianisation of Europe

"Never was there a war more prolonged nor more cruel than this, nor one that required greater efforts on the part of the Frankish people. For the Saxons (...) are by nature fierce, devoted to the worship of demons and hostile to our religion, and they think it no dishonour to confound and transgress the laws of God and man. On both sides of the frontier murder, robbery, and arson were of constant occurrence, so the Franks declared open war against them."

– Einhard on the origins of the Saxon Wars in Vita Karoli Magni (c. 820)[54]

According to Gregory of Tours' writings, King Clovis I of the Franks waged wars against other European nations who followed Arian Christianity, which was seen by Catholics as heretical. During his war with the Arian Visigoths, Clovis reportedly said: "I take it very hard that these Arians hold part of the Gauls. Let us go with God's help and conquer them and bring the land under our control."[55]

The Saxon Wars (772–804) of Frankish king Charlemagne against the Saxons under Widukind were described by Jim Bradbury (2004) as 'in essence a frontier struggle and a religious war against pagans – devil-worshippers according to Einhard.'[56] He noted that Charlemagne ordered the destruction of the Irminsul, an object sacred to the Saxons.[56] Per Ullidtz (2014) stated that previous Frankish–Saxon conflicts spanning almost a century 'had been mostly a border war', 'but under Charles it changed character': because of 'Charles' idea of unity, of a king over all German tribes, and of universal Christianity in all of his kingdom, it changed into a mission from heaven.'[57] Similarly, a successful Carolingian campaign against the Pannonian Avars in the 790s led to their forced conversion to Christianity.[56] The earlier Merovingian conquests of Thuringia, Allemannia and Bavaria had also resulted in their Christianisation by 555, although the Frisians resisted with similar determinacy as the Saxons during the Frisian–Frankish wars (7th and 8th century), with both tribes killing several Christian missionaries in defence of their Germanic paganism, to the horror of Christian hagiographers.[58]

Crusades

The Crusades are a prime example of wars whose religious elements have been extensively debated for centuries, with some groups of people in some periods emphasising, restoring or overstating the religious aspects, and other groups of people in some periods denying, nuancing or downplaying the religious aspects of the Crusades in favour of other factors. Winkler Prins/Encarta (2002) concluded: "The traditional explanation for the Crusades (a religious enthusiasm that found an outlet in a Holy War) has also retained its value in modern historical scholarship, keeping in mind the fact that it has been pointed out that a complex set of socio-economic and political factors allowed this enthusiasm to manifest itself."[59]

The Crusades against Muslim expansion in the 11th century were recognized as a "holy war" or a bellum sacrum by later writers in the 17th century. The early modern wars against the Ottoman Empire were seen as a seamless continuation of this conflict by contemporaries.[60]

Reconquista

Jim Bradbury (2004) noted that the belligerents in the Reconquista were not all equally motivated by religion, and that a distinction should be made between 'secular rulers' on the one hand, and on the other hand Christian military orders which came from elsewhere (including the three main orders of Knights Templar, Knights Hospitaller and Teutonic Knights), or were established inside Iberia (such as those of Santiago, Alcántara and Calatrava).[61] '[The Knights] were more committed to religious war than some of their secular counterparts, were opposed to treating with Muslims and carried out raids and even atrocities, such as decapitating Muslim prisoners.'[61]

The Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, known in Arab history as the Battle of Al-Uqab (معركة العقاب), was fought on 16 July 1212 and it was an important turning point in both the Reconquista and the medieval history of Spain.[62] The forces of King Alfonso VIII of Castile were joined by the armies of his Christian rivals, Sancho VII of Navarre, Pedro II of Aragon and Afonso II of Portugal in battle[63] against the Berber Muslim Almohad conquerors of the southern half of the Iberian Peninsula.

Hussite Wars

The relative importance of the various factors that caused the Hussite Wars (1419–1434) is debated. Kokkonen & Sundell (2017) claimed that the death of king Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia on 19 August 1419 is the event that sparked the Hussite rebellion against his nominal heir Sigismund (then king of Germany, Hungary and Croatia), making it essentially a war of succession.[64] Nolan (2006) named religion as one of several significant causes, summarising the Hussites' motives as 'doctrinal as well as "nationalistic" and constitutional', and providing a series of issues that led to war: the trial and execution of Jan Hus (1415) 'provoked the conflict', the Defenestration of Prague (30 July 1419) 'began the conflict', while 'fighting began after King Wenceslaus died, shortly after the defenestration' (that is, after 19 August 1419).[65] Nolan described the wars' goals and character as follows: 'The main aim of the Hussites was to prevent the hated Sigismund mounting the throne of Bohemia, but fighting between Bohemian Hussites and Catholics spread into Moravia. (...) cross-class support gave the Hussite Wars a tripartite and even "national" character unusual for the age, and a religious and social unity of purpose, faith, and hate'.[66] Winkler Prins/Encarta (2002) described the Hussites as a 'movement which developed from a religious denomination to a nationalist faction, opposed to German and Papal influence; in the bloody Hussite Wars (1419–1438), they managed to resist.' It didn't mention the succession of Wenceslaus by Sigismund,[67] but noted elsewhere that it was Sigismund's policy of Catholic Church unity which prompted him to urge Antipope John XXIII to convene the Council of Constance in 1414, which ultimately condemned Jan Hus.[68]

Soga–Mononobe conflict

Buddhism was formally introduced into Japan by missionaries from the kingdom of Baekje in 552. Adherents of the native Shinto religion resisted the spread of Buddhism, and several military conflicts broke out,[69] starting with the Soga–Mononobe conflict (552–587) between the pro-Shinto Mononobe clan (and Nakatomi clan) and the pro-Buddhist Soga clan. Although the political power each of the clans could wield over the royal family was also an important factor, and was arguably a strategic reason for the Soga to adopt and promote Buddhism as a means to increase their authority, the religious beliefs from both doctrines, as well as religious explanations from events that happened after the arrival of Buddhism, were also causes of the conflict that escalated to war.[70] Whereas the Soga argued that Buddhism was a better religion because it had come from China and Korea, whose civilisations were widely regarded as superior and to be emulated in Yamato (the central kingdom of Japan), the Mononobe and Nakatomi maintained that there should be continuity of tradition and that worshipping the native gods (kami) was in the best interest of the Japanese.[70] Unable to reach a decision, Emperor Kinmei (r. 539–571) maintained Shinto as the royal religion, but allowed the Soga to erect a temple for the statue of Buddha.[70] Afterwards, an epidemic broke out, which Shintoists attributed to the anger of the native gods to the intrusion of Buddhism; in reaction, some burnt down the Buddhist temple and threw the Buddha statue into a canal.[70] However, the epidemic worsened, which Buddhists in turn interpreted as the anger of Buddha to the sacrilege committed against his temple and statue.[70] Both during the 585 and 587 wars of succession, the opposing camps were drawn along the Shinto–Buddhist divide, and the Soga clan's victory resulted in the imposition of Buddhism as the Yamato court religion under the regency of Prince Shotoku.[70]

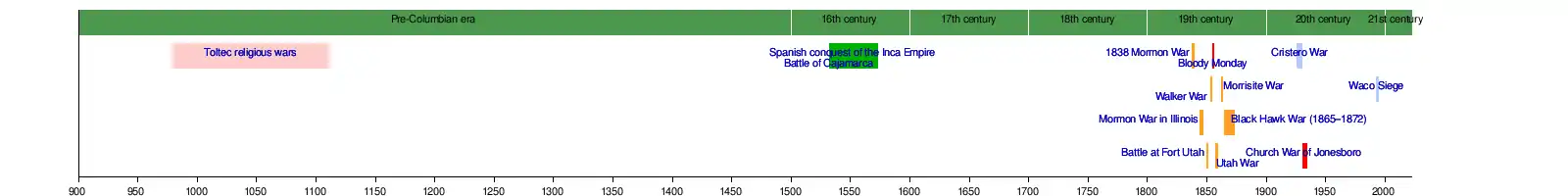

Toltec religious wars

There have been several religious wars in the Toltec Empire of Mesoamerica (c. 980–1110) between devotees of Tezcatlipoca and followers of Quetzalcoatl; the latter lost and were driven to flee to the Yucatán Peninsula.[71]

Early modern period

European wars of religion

The term "religious war" was used to describe, controversially at the time, what are now known as the European wars of religion, and especially the then-ongoing Seven Years' War, from at least the mid 18th century.[72] The Encyclopædia Britannica maintains that "[the] wars of religion of this period [were] fought mainly for confessional security and political gain".[73]

In 16th-century France, there was a series of wars between Roman Catholics and Protestants (Huguenots primarily), known as the French Wars of Religion. In the first half of the 17th century, the German states, Scandinavia (Sweden, primarily) and Poland were beset by religious warfare during the Thirty Years War. Roman Catholicism and Protestantism figured on the opposing sides of this conflict, though Catholic France took the side of the Protestants, but it did so for purely political reasons.

In the late 20th century, a number of revisionist historians such as William M. Lamont regarded the English Civil War (1642–1651) as a religious war, with John Morrill (1993) stating: 'The English Civil War was not the first European revolution: it was the last of the Wars of Religion.'[74] This view has been criticised by various pre-, post- and anti-revisionist historians.[74] Glen Burgess (1998) examined political propaganda written by the Parliamentarian politicians and clerics at the time, noting that many were or may have been motivated by their Puritan religious beliefs to support the war against the 'Catholic' king Charles I of England, but tried to express and legitimise their opposition and rebellion in terms of a legal revolt against a monarch who had violated crucial constitutional principles and thus had to be overthrown.[75] They even warned their Parliamentarian allies to not make overt use of religious arguments in making their case for war against the king.[75] However, in some cases it may be argued that they hid their pro-Anglican and anti-Catholic motives behind legal parlance, for example by emphasising that the Church of England was the legally established religion: 'Seen in this light, the defenses of Parliament's war, with their apparent legal-constitutional thrust, are not at all ways of saying that the struggle was not religious. On the contrary, they are ways of saying that it was.'[76] Burgess concluded: '[T]he Civil War left behind it just the sort of evidence that we could reasonably expect a war of religion to leave.'[77]

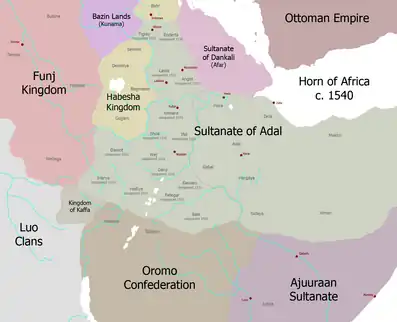

Ethiopian–Adal War

The Ethiopian–Adal War (1529–1543) was a military conflict between the Abyssinians and the Adal Sultanate. The Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi came close to extinguishing the ancient realm of Abyssinia, and forcibly converting all of its surviving subjects to Islam. The intervention of the European Cristóvão da Gama attempted to help to prevent this outcome, but he was killed by al-Ghazi. However, both polities exhausted their resources and manpower in this conflict, allowing the northward migration of the Oromo into their present homelands to the north and west of Addis Ababa.[78] Many historians trace the origins of hostility between Somalia and Ethiopia to this war.[79]

Modern period

Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence (1821–1829) has sometimes been considered a religious war between Christians and Muslims, especially in its early phase. The Greek Declaration of Independence (issued on 15 January 1822) legitimised the armed rebellion against the Ottoman Empire in a mix of religious and nationalist terms: 'The war we are waging against the Turks, far from being founded in demagoguery, seditiousness or the selfish interests of any one part of the Greek nation, is a national and holy war (...). It is from these principles of natural rights and desiring to assimilate ourselves with our European Christian brethren, that we have embarked upon our war against the Turks.'[80] Scottish writer Felicia Skene remarked in 1877: 'The Greek war of independence has never been called a religious war, and yet it had a better claim to that appellation than many a conflict which has been so named by the chroniclers of the past. It is a significant fact that the standard of revolt was raised by no mere patriot, but by Germanus, the aged Archbishop of Patras, who came forward, strong in his spiritual dignity (...) to be the first champion in the cause of Hellenic liberty.'[81] Ian Morris (1994) stated that 'the uprising in 1821 was mainly a religious war', but that philhellene Western volunteers joined the war for quite different reasons, namely to 'regenerate' Greece and thereby Europe, motivated by Romantic ideas about European history and civilisation, and Orientalist views of Ottoman culture.[82] The Filiki Eteria, the main organisation driving the rebellion, was split between two groups: one advocated the restoration of the Byzantine Empire on religious grounds, and to encourage all Christians within Ottoman territory to join the Greek revolutionaries; the other advocated the Megali Idea, a large Greek nation-state based on shared language rather than religion.[82] Both of these grand objectives failed, but a smaller version of the latter goal was accepted by most members of the Eteria by 1823, and this goal was generally compatible with the motives of philhellenes who travelled to Greece to enter the war in 1821–23.[82]

Israeli–Palestinian conflict

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict can primarily be viewed as an ethnic conflict between two parties where one party is most often portrayed as a singular ethno-religious group which only consists of the Jewish majority and ignores non-Jewish minority Israeli citizens who support the existence of a State of Israel to varying degrees, especially the Druze and the Circassians who, for example, volunteer to serve in the IDF, participate in combat and are represented in the Israeli parliament in greater percentages than Israeli Jews are[83][84] as well as Israeli Arabs, Samaritans,[85] various other Christians, and Negev Bedouin;[86] the other party is sometimes presented as an ethnic group which is multi-religious (although most numerously consisting of Muslims, then Christians, then other religious groups up to and including Samaritans and even Jews). Yet despite the multi-religious composition of both of the parties in the conflict, elements on both sides often view it as a religious war between Jews and Muslims. In 1929, religious tensions between Muslim and Jewish Palestinians over the latter praying at the Wailing Wall led to the 1929 Palestine riots, including the Hebron and Safed massacres.[87]

In 1947, the UN's decision to partition the Mandate of Palestine, led to the creation of the state of Israel and Jordan, which annexed the West Bank portion of the mandate, since then, the region has been plagued with conflict. The 1948 Palestinian exodus also known as the Nakba (Arabic: النكبة),[88] occurred when approximately 711,000 to 726,000 Palestinian Arabs fled or were expelled from their homes, during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War and the Civil War that preceded it.[89] The exact number of refugees is a matter of dispute, though the number of Palestine refugees and their unsettled descendants registered with UNRWA is more than 4.3 million.[90][91] The causes remain the subject of fundamental disagreement between Palestinians and Israelis. Both Jews and Palestinians make ethnic and historical claims to the land, and Jews make religious claims as well.[92]

Pakistan and India

The All India Muslim League (AIML) was formed in Dhaka in 1906 by Muslims who were suspicious of the Hindu-majority Indian National Congress. They complained that Muslim members did not have the same rights as Hindu members. A number of different scenarios were proposed at various times. This was fuelled by the British policy of "Divide and Rule", which they tried to bring upon every political situation. Among the first to make the demand for a separate state was the writer/philosopher Allama Iqbal, who, in his presidential address to the 1930 convention of the Muslim League said that a separate nation for Muslims was essential in an otherwise Hindu-dominated subcontinent.

After the dissolution of the British Raj in 1947, British India was partitioned into two new sovereign states—the Dominion of India and the Dominion of Pakistan. In the resulting Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948, up to 12.5 million people were displaced, with estimates of loss of life varying from several hundred thousand to a million.[93] India emerged as a secular nation with a Hindu majority, while Pakistan was established as an Islamic republic with Muslim majority population.[94][95]

Nigerian conflict

Inter-ethnic conflict in Nigeria has generally had a religious element. Riots against Igbo in 1953 and in the 1960s in the north were said to have been sparked by religious conflict. The riots against Igbo in the north in 1966 were said to have been inspired by radio reports of mistreatment of Muslims in the south.[96] A military coup d'état led by lower and middle-ranking officers, some of them Igbo, overthrew the NPC-NCNC dominated government. Prime Minister Balewa along with other northern and western government officials were assassinated during the coup. The coup was considered an Igbo plot to overthrow the northern dominated government. A counter-coup was launched by mostly northern troops. Between June and July there was a mass exodus of Ibo from the north and west. Over 1.3 million Ibo fled the neighboring regions in order to escape persecution as anti-Ibo riots increased. The aftermath of the anti-Ibo riots led many to believe that security could only be gained by separating from the North.[97]

In the 1980s, serious outbreaks between Christians and Muslims occurred in Kafanchan in southern Kaduna State in a border area between the two religions.

The 2010 Jos riots saw clashes between Muslim herders against Christian farmers near the volatile city of Jos, resulting in hundreds of casualties.[98] Officials estimated that 500 people were massacred in night-time raids by rampaging Muslim gangs.[99]

Buddhist uprising

During the rule of the Catholic Ngo Dinh Diem in South Vietnam, the discrimination against the majority Buddhist population generated the growth of Buddhist institutions as they sought to participate in national politics and gain better treatment. The Buddhist Uprising of 1966 was a period of civil and military unrest in South Vietnam, largely focused in the I Corps area in the north of the country in central Vietnam.[100]

In a country where the Buddhist majority was estimated to be between 70 and 90 percent,[101][102][103][104][105] Diem ruled with a strong religious bias. As a member of the Catholic Vietnamese minority, he pursued pro-Catholic policies that antagonized many Buddhists.

Chinese conflict

The Dungan revolt (1862–1877) and Panthay Rebellion (1856–1873) by the Hui were also set off by racial antagonism and class warfare, rather than the mistaken assumption that it was all due to Islam that the rebellions broke out.[106] During the Dungan revolt fighting broke out between Uyghurs and Hui.

In 1936, after Sheng Shicai expelled 20,000 Kazakhs from Xinjiang to Qinghai, the Hui led by General Ma Bufang massacred their fellow Muslims, the Kazakhs, until there were only 135 of them left.[107][108]

Tensions with Uyghurs and Hui arose because Qing and Republican Chinese authorities used Hui troops and officials to dominate the Uyghurs and crush Uyghur revolts.[109] Xinjiang's Hui population increased by over 520 percent between 1940 and 1982, an average annual growth rate of 4.4 percent, while the Uyghur population only grew by 1.7 percent. This dramatic increase in the Hui population led inevitably to significant tensions between the Hui and Uyghur Muslim populations. Some old Uyghurs in Kashgar remember that the Hui army at the Battle of Kashgar (1934) massacred 2,000 to 8,000 Uyghurs, which caused tension as more Hui moved into Kashgar from other parts of China.[110] Some Hui criticize Uyghur separatism, and generally do not want to get involved in conflicts in other countries over Islam for fear of being perceived as radical.[111] Hui and Uyghur live apart from each other, praying separately and attending different mosques.[112]

Lebanese Civil War

There is no consensus among scholars on what triggered the Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990). However, the militarization of the Palestinian refugee population, along with the arrival of the PLO guerrilla forces, sparked an arms race for the different Lebanese political factions. However, the conflict played out along three religious lines: Sunni Muslim, Christian Lebanese and Shiite Muslim, Druze are considered among Shiite Muslims.

It has been argued that the antecedents of the war can be traced back to the conflicts and political compromises reached after the end of Lebanon's administration by the Ottoman Empire. The Cold War had a powerful disintegrative effect on Lebanon, which was closely linked to the polarization that preceded the 1958 political crisis. During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, an exodus of Palestinian refugees, who fled the fighting or were expelled from their homes, arrived in Lebanon. Palestinians came to play a very important role in future Lebanese civil conflicts, and the establishment of Israel radically changed the local environment in which Lebanon found itself.

Lebanon was promised independence, which was achieved on 22 November 1943. Free French troops, who had invaded Lebanon in 1941 to rid Beirut of the Vichy French forces, left the country in 1946. The Christians assumed power over the country and its economy. A confessional Parliament was created in which Muslims and Christians were given quotas of seats. As well, the president was to be a Christian, the prime minister a Sunni Muslim and the speaker of Parliament a Shia Muslim.

In March 1991, Parliament passed an amnesty law that pardoned all political crimes prior to its enactment. The amnesty was not extended to crimes perpetrated against foreign diplomats or certain crimes referred by the cabinet to the Higher Judicial Council. In May 1991, the militias (with the important exception of Hezbollah) were dissolved, and the Lebanese Armed Forces began slowly to rebuild themselves as Lebanon's only major non-sectarian institution.

Some violence still occurred. In late December 1991 a car bomb (estimated to carry 220 pounds of TNT) exploded in the Muslim neighborhood of Basta. At least 30 people were killed, and 120 wounded, including former Prime Minister Shafik Wazzan, who was riding in a bulletproof car.

Iran–Iraq War

In the case of the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), the new revolutionary government of the Islamic Republic of Iran generally described the conflict as a religious war,[113] and used the narrative of jihad to recruit, mobilise and motivate its troops.[113][114]: 9:24, 16:05 On the other hand, justifications from the Saddam Hussein-led Ba'athist Iraq were mostly framed in terms of a supposed Persian–Arab historical enmity, and Iraq-centred Arab nationalism (including support for Arab separatism in Khuzestan).[113] Some of the underlying motives of Saddam appear to have been controlling the Shatt al-Arab waterway and region (previously settled by the 1975 Algiers Agreement, which had ended Imperial Iranian support for the 1974–75 Kurdish rebellion against the Iraqi government[114]: 3:27 ), obtaining access to the oil reserves in Khuzestan, and exploiting the instability of post-Revolution Iran, including the failed 1979 Khuzestan insurgency.[114]: 3:06 Peyman Asadzade (2019) stated: 'Although the evidence suggests that religious motivations by no means contributed to Saddam's decision to launch the war, an overview of the Iranian leaders' speeches and martyrs' statements reveals that religion significantly motivated people to take part in the war. (...) The Iranian leadership painted the war as a battle between believers and unbelievers, Muslims and infidels, and the true and the false.'[113] Iran cited religious reasons to justify continuing combat operations, for example in the face of Saddam's offer of peace in mid-1982, rejected by Ayatollah Khomeini's declaration that the war would not end until Iran had defeated the Ba'athist regime and replaced it with an Islamic republic.[114]: 8:16

While Ba'athist Iraq has sometimes been described as a 'secular dictatorship' before the war, and therefore in ideological conflict with the Shia Islamic 'theocracy' which seized control of Iran in 1979,[114]: 3:40 Iraq also launched the so-called Tawakalna ala Allah ("Trust in God") Operations (April–July 1988) in the final stages of the war.[114]: 16:05 Moreover, the Anfal campaign (1986–1989; in strict sense February–September 1988) was code-named after Al-Anfal, the eighth sura of the Qur'an which narrates the triumph of 313 followers of the new Muslim faith over almost 900 pagans at the Battle of Badr in the year 624.[115] "Al Anfal" literally means the spoils (of war) and was used to describe the military campaign of extermination and looting commanded by Ali Hassan al-Majid (also known as "Chemical Ali").[115] His orders informed jash (Kurdish collaborators with the Baathists, literally "donkey's foal" in Kurdish) units that taking cattle, sheep, goats, money, weapons and even women as spoils of war was halal (religiously permitted or legal).[115] Randal (1998, 2019) argued that 'Al Anfal' was 'a curious nod to Islam' by the Ba'athist government, because it had originally been known as a 'militantly secular regime'.[115] Some commentators have concluded that the code name was meant to serve as 'a religious justification' for the campaign against the Kurds.[116]

Yugoslav Wars

The Croatian War (1991–95) and the Bosnian War (1992–95) have been viewed as religious wars between the Orthodox, Catholic and Muslim populations of former Yugoslavia: respectively called "Serbs", "Croats" and "Bosniaks" (or "Bosnian Muslims").[117][118] Traditional religious symbols were used during the wars.[119] Notably, foreign Muslim volunteers came to Bosnia to wage jihad and were thus known as "Bosnian mujahideen". Although some news media and some scholars at the time and in the aftermath often described the conflicts as nationalist or ethnic in nature,[note 1] others such as the literary critic Christopher Hitchens (2007) have argued that they were religious wars[note 1] (Catholic versus Orthodox versus Islamic), and that terms such as "Serb" and "Croat" were employed as mere euphemisms to conceal the religious core of the armed conflicts, even though the term "Muslims" was frequently used.[120][note 2] Some scholars have stated that they "were not religious wars", but acknowledged that "religion played an important role in the wars" and "did often serve as the motivating and integrating factor for justifying military attacks".[note 1]

Sudanese Civil War

The Second Sudanese Civil War from 1983 to 2005 has been described as an ethnoreligious conflict where the Muslim central government's pursuits to impose sharia law on non-Muslim southerners led to violence, and eventually to the civil war. The war resulted in the independence of South Sudan six years after the war ended. Sudan is majority-Muslim and South Sudan is majority-Christian.[123][124][125][126]

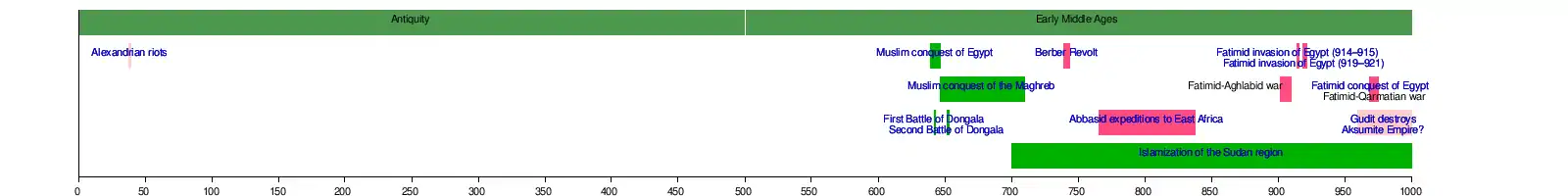

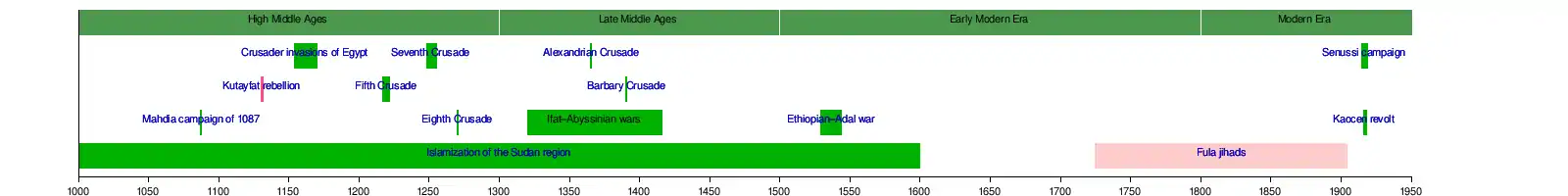

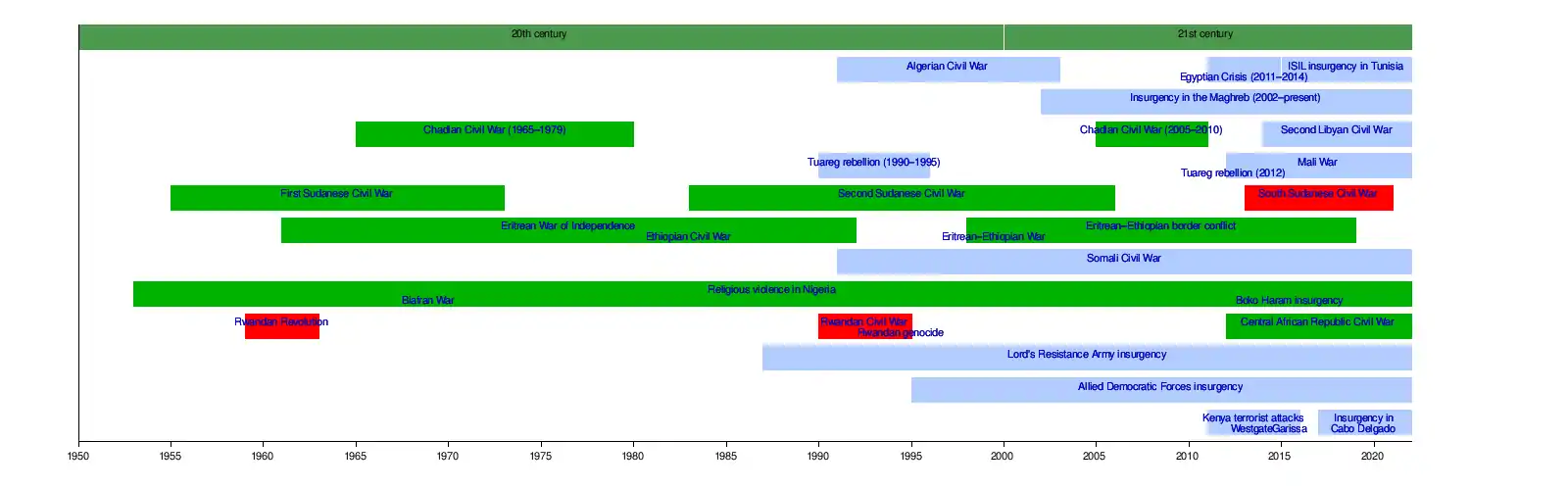

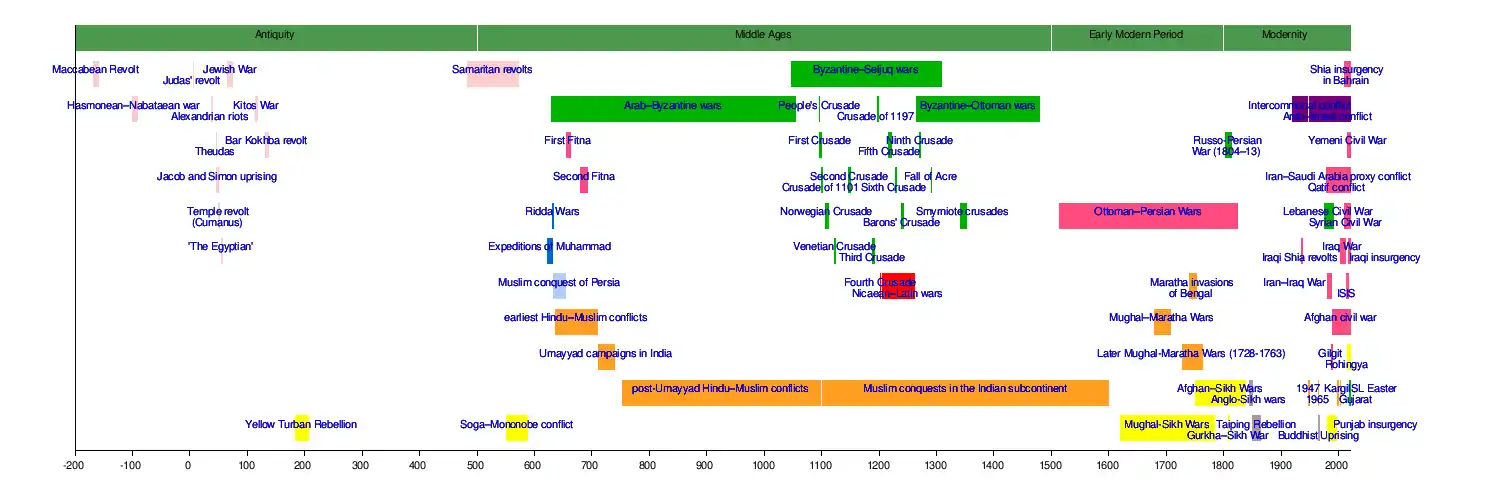

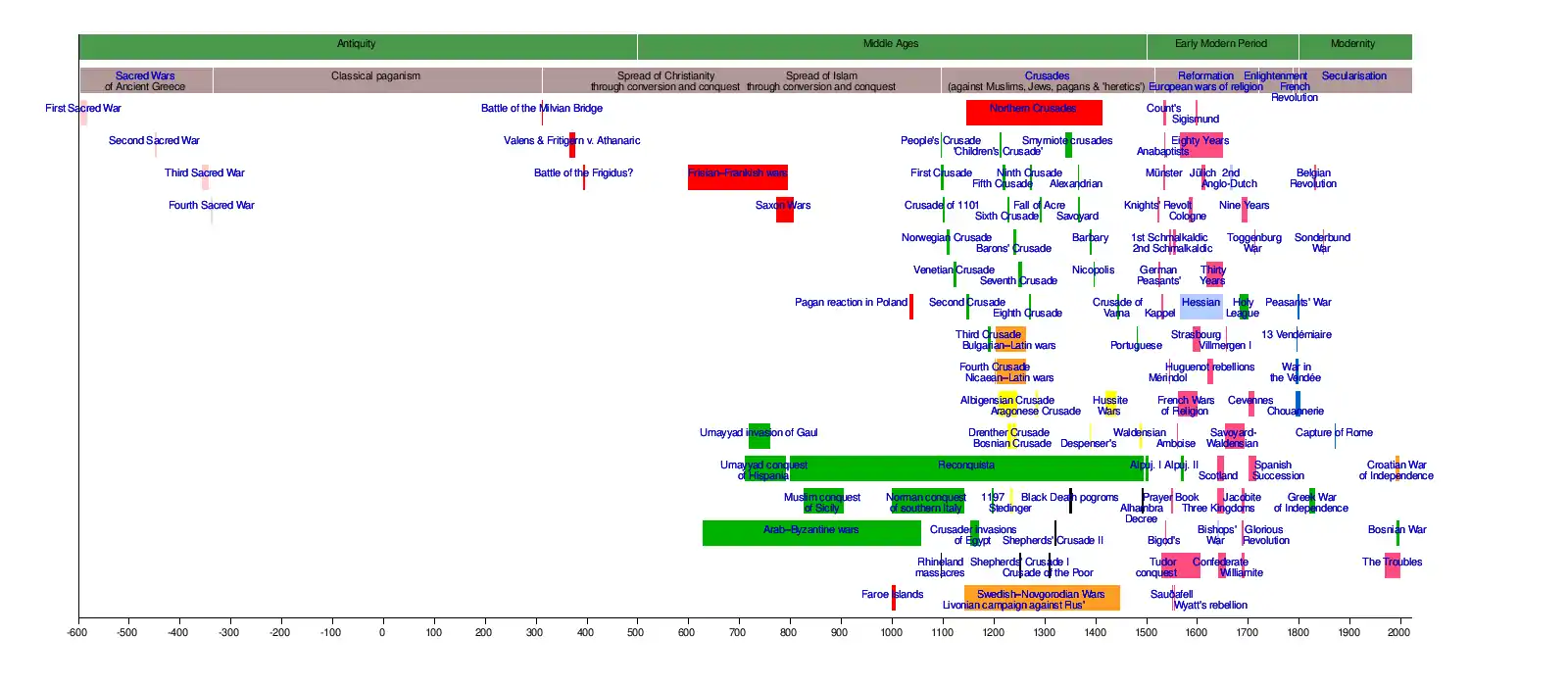

Timeline

Africa

- Abrahamic–polytheist conflict

- Christian–Islamic conflict

- Inter-Islamic conflict (e.g. Sunni–Shia)

- Inter-Christian conflict

- Islamist or Christian fundamentalist insurgency against secular government

Americas

- Inter–Indigenous conflicts

- Christian–Indigenous conflicts

- Mormon wars

- Inter-Christian conflict

- Christian fundamentalist insurgency against secular government

Asia

- Judaic–polytheist conflict

- Inter-Eastern religious conflict (Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Shinto)

- Islamic–polytheist Arab conflict

- Islamic–Zoroastrian conflict

- Inter-Islamic conflict (Sunni–Shia)

- Islamic–Hindu conflict

- Christian–Islamic conflict

- Inter-Christian conflict (Catholic–Orthodox)

- Christian–Eastern religious conflict

- Islamic–Judaic conflict

Europe

- Inter-pagan conflict

- Christian–pagan conflict

- Christian–'heretic' conflict

- Christian–Islamic conflict

- Catholic–Orthodox conflict

- Catholic–Protestant conflict

- Inter-Protestant conflict

- Anti-Jewish pogrom

- Christian–secularist conflict

See also

Notes

- Črnič & Lesjak (2003): "Religion played an important role in the wars, which took place in the early and mid 1990s, and shattered a large part of the Balkans (see Velikonja 2003). These were not religious wars in which Serbian Christian (Orthodox) troops would assume the role of the last bastian against the Muslim advance on the West, although this is how they were often interpreted in Western Europe and the USA. However, religion did often serve as the motivating and integrating factor for justifying military attacks that were actually nationalistic in nature. Thus, religion was merged with national identity. It was made to appear that all (real) Serbs had to be Orthodox, just as all Croatians had to be Catholics, and Bosnians had to be Muslims."[122]

- The term "Muslims" was a broad Yugoslav religious demographic designation which applied to all Slavic-speaking Islamic inhabitants of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia since 1971. It included the Gorani and the Macedonian Muslims (Torbeši), but mostly consisted of the group of people who would not be officially be called "Bosniaks" until 1993, namely, Muslims speaking the BCMS language. This decision was made by the Party of Democratic Action (SDA) on 27 September 1993,[121] see Bosniaks § Identity.

References

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton (2012). Exposing Myths about Christianity. Downers Grove, Ill.: IVP Books. pp. 56. ISBN 9780830834662.

- Cavanaugh, William T. (2009). The Myth of Religious Violence : Secular Ideology and the Roots of Modern Conflict. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538504-5.

- Morreall, John; Sonn, Tamara (2013). 50 Great Myths of Religion. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 39–44. ISBN 9780470673508.

- Entick, John (1763). The General History of the Later War. Vol. 3. p. 110.

- Omar, Irfan; Duffey, Michael, eds. (22 June 2015). "Introduction". Peacemaking and the Challenge of Violence in World Religions. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 1. ISBN 9781118953426.

This book does not ignore violence committed in the name of religion. Analyses of case studies of seeming religious violence often conclude that ethnic animosities strongly drive violence.

- Axelrod, Alan; Phillips, Charles, eds. (2004). Encyclopedia of Wars (Vol.3). Facts on File. pp. 1484–1485 "Religious wars". ISBN 0816028516.

- Matthew White (2011). The Great Big Book of Horrible Things. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 544. ISBN 978-0-393-08192-3.

- Holt, Andrew (8 November 2018). "Religion and the 100 Worst Atrocities in History". Andrew Holt, Ph.D. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- Onnekink, David (2013). War and Religion after Westphalia, 1648–1713. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 76–77. ISBN 9781409480211. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- Luard, Evan (1992). "Succession". The Balance of Power. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 149–150. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-21927-8_6. ISBN 978-1-349-21929-2. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- Morreall, John; Sonn, Tamara (2013). "Myth 8. Religion Causes Violence". 50 Great Myths of Religion. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 39–44. ISBN 9780470673508.

- Harrison, Peter (2015). The Territories of Science and Religion. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226184487.

- Nongbri, Brent (2013). Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300154160.

- Hershel Edelheit, Abraham J. Edelheit, History of Zionism: A Handbook and Dictionary Archived 24 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, p. 3, citing Solomon Zeitlin, The Jews. Race, Nation, or Religion? ( Philadelphia: Dropsie College Press, 1936).

- Josephson, Jason Ananda (2012). The Invention of Religion in Japan. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226412344.

- Müller, Friedrich Max (1873). Introduction to the Science of Religion: four lectures delivered at the Royal institution, with two essays, On false analogies, and The philosophy of mythology. London: Longmans, Green, and co. p. 28.

- Kuroda, Toshio and Jacqueline I. Stone, translator. "The Imperial Law and the Buddhist Law" (PDF). Archived from the original on 23 March 2003. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 23.3-4 (1996) - Neil McMullin. Buddhism and the State in Sixteenth-Century Japan. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, 1984.

- McGarry J, O'Leary B, 1995. Explaining Northern Ireland: Broken Images. Oxford, Blackwell

- Holsti 1991, p. 308.

- Andrew Holt Ph. D (26 December 2018). "Counting "Religious Wars" in the Encyclopedia of Wars". Andrew Holt, Ph.D. Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- Axelrod, Alan & Phillips, Charles Encyclopedia of Wars Vol.1, Facts on File, November 2004, ISBN 978-0-8160-2851-1. p.xxii. "Wars have always arisen, and arise today, from territorial disputes, military rivalries, conflicts of ethnicity, and strivings for commercial and economic advantage, and they have always depended on, and depend on today, pride, prejudice, coercion, envy, cupidity, competitiveness, and a sense of injustice. But for much of the world before the 17th century, these “reasons” for war were explained and justified, at least for the participants, by religion. Then, around the middle of the 17th century, Europeans began to conceive of war as a legitimate means of furthering the interests of individual sovereigns."

- Sheiman, Bruce (2009). An Atheist Defends Religion : Why Humanity is Better Off with Religion than Without It. Alpha Books. pp. 117–118. ISBN 978-1592578542.

- Day, Vox (2008). The Irrational Atheist: Dissecting the Unholy Trinity of Dawkins, Harris, and Hitchens. BenBella Books. pp. 104–106. ISBN 978-1933771366.

- Lurie, Alan (10 April 2012). "Is Religion the Cause of Most Wars?". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- "The Encyclopedia of War" by Gordon Martel (17 Jan 2012, 2912 pages)

- Jonathan Kirsch God Against The Gods: The History of the War Between Monotheism and Polytheism, Penguin, 2005.

- Burkert, Greek Religion, p. 170.

- "Here each company of youths sacrifices a puppy to Enyalius, holding that the most valiant of tame animals is an acceptable victim to the most valiant of the gods. I know of no other Greeks who are accustomed to sacrifice puppies except the people of Colophon; these too sacrifice a puppy, a black bitch, to the Wayside Goddess." Pausanias, 3.14.9.

- Barstad, Hans M. (2008). History and the Hebrew Bible: Studies in Ancient Israelite and Ancient Near Eastern Historiography. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. p. 57. ISBN 9783161498091. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- Peters, Edward (1998). "Introduction". The First Crusade: The Chronicle of Fulcher of Chartres and Other Source Materials (2 ed.). Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812216563. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- Levine, David. "Conflicts of Ideology in Christian and Muslim Holy War". Binghamton University. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- Abels, Richard. "Timeline for the Crusades and Christian Holy War". US Naval Academy. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- Tyerman, Christopher. The Crusades: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, London, 2004. PP. 63.

- "Christian Jihad: The Crusades and Killing in the Name of Christ". Cbn.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2008. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- Kaushik Roy. Hinduism and the Ethics of Warfare in South Asia: From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University. p. 28.

- Roy, Kaushik (2012). Hinduism and the Ethics of Warfare in South Asia: From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 9781107017368. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- Johnson, James Turner (1997). "Two Cultures, Two Traditions: Opening a Dialogue". Holy War Idea in Western and Islamic Traditions. Penn State Press. pp. 20–25. ISBN 978-0-271-04214-5.

- Khadduri, Majid (1955). War and Peace in the Law of Islam. Johns Hopkins Press. pp. 55–56.

- William M. Watt: Muhammad at Medina, p.4; q.v. the Tafsir regarding these verses

- Firestone 2012, p. 3.

- Holy War in Judaism: The Fall and Rise of a Controversial Idea

- Firestone, Reuven. "Holy War Idea in the Hebrew Bible" (PDF). USC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- Niditch, Susan (1995). "War in the Hebrew Bible and Contemporary Parallels" (PDF). Word & World. Luther Seminary. 15 (4): 406. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- Hamilton, Victor P. (2005). Handbook on the Pentateuch: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books. p. 371. ISBN 9781585583003. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- Olson, Dennis T. (2012). "Numbers 31. War against the Midianites: Judgment for Past Sin, Foretaste of a Future Conquest". Numbers. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 176–180. ISBN 9780664238827. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- Rad, Gerhard von (2016) [1958]. Holy War in Ancient Israel. Translated by Marva J. Dawn. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-0528-7.

- Dhavan, Purnima (2011). When Sparrows Became Hawks: The Making of the Sikh Warrior Tradition, 1699-1799. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 76. ISBN 9780199756551. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- Chima, Jugdep S. (2008). The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India. p. 70. ISBN 9788132105381. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- Fenech, Louis E.; McLeod, W. H. (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Plymouth & Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 99–100. ISBN 9781442236011. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- Schnabel, Albrecht; Gunaratna, Rohan (2015). Wars From Within: Understanding And Managing Insurgent Movements. London: Imperial College Press. p. 194. ISBN 9781783265596. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- Syan, Hardip Singh (2013). Sikh Militancy in the Seventeenth Century: Religious Violence in Mughal and Early Modern India. London & New York: I.B.Tauris. pp. 3–4, 252. ISBN 9781780762500. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Encarta Encyclopaedia Winkler Prins s.v. "Delphi".

- Ullidtz 2014, p. 127.

- Gregory of Tours, A History of the Franks, Pantianos Classics, 1916

- Bradbury 2004, p. 21.

- Ullidtz, Per (2014). 1016: The Danish Conquest of England. Copenhagen: Books on Demand. p. 126. ISBN 978-87-7145-720-9.

- Ullidtz 2014, p. 126.

- Encarta Winkler Prins Encyclopaedia (1993–2002) s.v. "kruistochten". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- E.g. Bellum sacrum Ecclesiae militantis contra Turcum by Léonard de Vaux (1685).

- Bradbury 2004, p. 314.

- Lynn Hunt describes the battle as a "major turning point in the reconquista..." See Lynn Hunt, R. Po-chia Hsia, Thomas R. Martin, Barbara H. Rosenwein, and Bonnie Smith, The Making of the West: Peoples and Cultures: A Concise History: Volume I: To 1740, Second Edition (New York: Bedford/St. Martin's 2007), 391.

- Guggenberger, Anthony, A General History of the Christian Era: The Papacy and the Empire, Vol.1, (B. Herder, 1913), 372.

- Kokkonen & Sundell 2017, Appendix, p. 22.

- Nolan 2006, p. 428–429.

- Nolan 2006, p. 429.

- Encarta Winkler Prins Encyclopaedia (1993–2002) s.v. "hussieten". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- Encarta Winkler Prins Encyclopaedia (1993–2002) s.v. "Sigismund [Duitse Rijk]". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Japan. §5.2 De introductie van de vastelandsbeschaving". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- Wolff, Richard (2007). The Popular Encyclopedia of World Religions. Harvest House Publishers. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0736920070.

- Encarta-encyclopedie Winkler Prins (1993–2002) s.v. "Tolteken". Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum.

- Israel Mauduit, Considerations on the Present German War, 1759, p. 25 Archived 7 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. John Entick, The General History of the Later War, Volume 3, 1763, p. 110 Archived 17 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- John Hearsey McMillan Salmon. "The Wars of Religion". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- Burgess 1998, p. 175.

- Burgess 1998, p. 196–197.

- Burgess 1998, p. 198–200.

- Burgess 1998, p. 201.

- See, for example, Richard Pankhurst, The Ethiopians: A History (Oxford: Blackwell, 2001), pp. 96f and sources cited therein.

- For example, David D. Laitin and Said S. Samatar, Somalia: Nation in Search of a State (Boulder: Westview Press, 1987).

- "Greek Declaration of Independence". English Wikisource. 15 January 1822. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- Skene, Felicia (1877). The Life of Alexander Lycurgus, Archbishop of the Cyclades. London: Rivingtons. p. 3. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- Morris, Ian (1994). Classical Greece: Ancient Histories and Modern Archaeologies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780521456784. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- Merza, Eleonore (2008). "In search of a lost time". Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem (19): 24. ISSN 2075-5287.

- Adelman, Jonathan (8 October 2015). "The Druze of Israel: Hope for Arab-Jewish Collaboration". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- "Samaritans form bridge of peace between Israelis and Palestinians". Financial Times. 22 April 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- "Muslim Arab Bedouins serve as Jewish state's gatekeepers". Al Arabiya English. 24 April 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- Segev, Tom (1999). One Palestine, Complete. Metropolitan Books. pp. 295–313. ISBN 0-8050-4848-0.

- Stern, Yoav. "Palestinian refugees, Israeli left-wingers mark Nakba" Archived 23 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Ha'aretz, Tel Aviv, 13 May 2008; Nakba 60 Archived 12 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights; Cleveland, William L. A History of the Modern Middle East, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2004, p. 270. ISBN 978-0-8133-4047-0

- McDowall, David; Claire Palley (1987). The Palestinians. Minority Rights Group Report no 24. p. 10. ISBN 0-946690-42-1.

- "The United Nations and Palestinian Refugees" (PDF). Unrwa.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- Pedahzur, Ami; Perliger, Arie (2010). "The Consequences of Counterterrorist Policies in Israel". In Crenshaw, Martha (ed.). The Consequences of Counterterrorism. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-87154-073-7. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Carter, Jimmy. Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid. Simon & Schuster, 2006. ISBN 0-7432-8502-6

- Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 221–222

- "Census of India : Religious Composition". Censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- Archived 22 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Kevin Lewis O'Neill (March 2009). Alexander Laban Hilton (ed.). Genocide: truth, memory, and representation. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4405-6.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refworld - Chronology for Ibo in Nigeria". Refworld. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- "Nigeria violence: Muslim-Christian clashes kill hundreds". CSMonitor.com. 8 March 2010. Archived from the original on 11 March 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- Clayton, Jonathan; Gledhill, Ruth (8 March 2010). "500 butchered in Nigeria killing fields". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 30 August 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- Archived 15 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Moyar (2006), pp. 215–16.

- "The Religious Crisis". Time. 14 June 1963. Archived from the original on 4 December 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- Tucker, pp. 49, 291, 293.

- Maclear, p. 63.

- "The Situation In South Vietnam - SNIE 53-2-63". The Pentagon Papers, Gravel Edition, Volume 2. 10 July 1963. pp. 729–733. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- John Alexander Selbie, Louis Herbert Gray 1916 893

- American Academy of Political and Social Science (1951). The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volume 277. American Academy of Political and Social Science. p. 152. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- American Academy of Political and Social Science (1951). Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volumes 276-278. American Academy of Political and Social Science. p. 152. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- S. Frederick Starr (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim borderland. M.E. Sharpe. p. 311. ISBN 0-7656-1318-2. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- S. Frederick Starr (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim borderland. M.E. Sharpe. p. 113. ISBN 0-7656-1318-2. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Van Wie Davis, Elizabeth. "Uyghur Muslim Ethnic Separatism in Xinjiang, China". Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - William Safran (1998). Nationalism and ethnoregional identities in China. Psychology Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-7146-4921-X. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- Asadzade, Peyman (25 June 2019). "War and Religion: The Iran−Iraq War". Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.812. ISBN 978-0-19-022863-7. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- Griffin Johnson (9 November 2019). "Iran-Iraq War | Animated History". The Armchair Historian. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- Randal, Jonathan C. (2019). After Such Knowledge, What Forgiveness?: My Encounters With Kurdistan. Routledge. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-429-71113-8.

- Dave Johns (24 January 2006). "The Crimes of Saddam Hussein – 1988 The Anfal Campaign". Saddam's Road to Hell. PBS Frontline. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- Branislav Radeljić; Martina Topić (1 July 2015). Religion in the Post-Yugoslav Context. Lexington Books. pp. 5–11. ISBN 978-1-4985-2248-9.

- Kevin Boyle; Juliet Sheen (1997). Freedom of Religion and Belief: A World Report. Psychology Press. pp. 409 ff. ISBN 978-0-415-15977-7.

- Velikonja, Mitja. "In hoc signo vinces: religious symbolism in the Balkan wars 1991–1995." International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 17.1 (2003): 25-40.

- Hitchens, Christopher (2011). "Religion Kills". God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything. London: Atlantic Books. pp. 22–24. ISBN 9780857897152. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

In effect, the extremist Catholic and Orthodox forces were colluding in a bloody partition and cleansing of Bosnia–Herzegovina. They were, and still are, largely spared the public shame of this, because the world's media preferred the simplification of "Croat" and "Serb", and only mentioned religion when discussing "the Muslims." But the triad of terms "Croat," "Serb," and "Muslim" is unequal and misleading, in that it equates two nationalities and one religion. (The same blunder is made in a different way in coverage of Iraq, with the "Sunni-Shia-Kurd" trilateral.)

- Bougarel, Xavier (2009). "Od "Muslimana" do "Bošnjaka": pitanje nacionalnog imena bosanskih muslimana" [From "Muslims" to "Bosniaks": the question of the national name of the Bosnian Muslims]. Rasprave o nacionalnom identitetu Bošnjaka – Zbornik radova [The discussions on the national identity of Bosniaks - a collection of papers]. p. 128.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Črnič, Aleš; Lesjak, Gregor (2003). "Religious Freedom and Control in Independent Slovenia". Sociology of Religion. Oxford University Press. 64 (3): 349–350. doi:10.2307/3712489. JSTOR 3712489.

- "Sudan". Country Studies. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

The factors that provoked the military coup, primarily the closely intertwined issues of Islamic law and of the civil war in the south, remained unresolved in 1991. The September 1983 implementation of the sharia throughout the country had been controversial and provoked widespread resistance in the predominantly non-Muslim south ... Opposition to the sharia, especially to the application of hudud (sing., hadd), or Islamic penalties, such as the public amputation of hands for theft, was not confined to the south and had been a principal factor leading to the popular uprising of April 1985 that overthrew the government of Jaafar an Nimeiri

- "PBS Frontline: "Civil war was sparked in 1983 when the military regime tried to impose sharia law as part of its overall policy to "Islamicize" all of Sudan."". Pbs.org. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- "Sudan at War With Itself" (PDF). The Washington Post. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2008.

The war flared again in 1983 after then-President Jaafar Nimeri abrogated the peace accord and announced he would turn Sudan into a Muslim Arab state, where Islamic law, or sharia, would prevail, including in the southern provinces. Sharia can include amputation of limbs for theft, public flogging and stoning. The war, fought between the government and several rebel groups, continued for two decades.

- Tibi, Bassam (2008). Political Islam, World Politics and Europe. Routledge. p. 33. "The shari'a was imposed on non-Muslim Sudanese peoples in September 1983, and since that time Muslims in the north have been fighting a jihad against the non-Muslims in the south."

Bibliography

- Bradbury, Jim (2004). The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 21, 314. ISBN 9781134598472. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Burgess, Glenn (1998). "Was the English Civil War a War of Religion? The Evidence of Political Propaganda". Huntington Library Quarterly. University of California Press. 61 (2): 173–201. doi:10.2307/3817797. JSTOR 3817797. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- Cliff, Nigel (2011). Holy War: How Vasco da Gama's Epic Voyages Turned the Tide in a Centuries-Old Clash of Civilizations, HarperCollins, ISBN 9780062097101.

- Crowley, Roger (2013). 1453: The Holy War for Constantinople and the Clash of Islam and the West, Hyperion, ISBN 9781401305581.

- Firestone, Reuven (2012). Holy War in Judaism: The Fall and Rise of a Controversial Idea. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199860302.001.0001. ISBN 9780199860302. S2CID 160968766.

- Hashmi, Sohail H. (2012). Just Wars, Holy Wars, and Jihads: Christian, Jewish, and Muslim Encounters and Exchanges, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199755035.

- Holsti, Kalevi (1991). Peace and War: Armed Conflicts and International Order, 1648–1989. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 379. ISBN 9780521399296.

- Johnson, James Turner (1997).The Holy War Idea in Western and Islamic Traditions, Pennsylvania State University Press, ISBN 9780271042145.

- Kirby, Dianne Religion and the Cold War, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 9781137339430 (2013 reprint)

- Kokkonen, Andrej; Sundell, Anders (September 2017). Online supplementary appendix for "The King is Dead: Political Succession and War in Europe, 1000–1799" (PDF). Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg. p. 40. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- Metcalf, Barbara D.; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006). A Concise History of India (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68225-1.

- Miner, Steven Merritt (2003). Stalin's Holy War: Religion, Nationalism, and Alliance Politics, 1941-1945, Univ of North Carolina Press, ISBN 9780807862124.

- Mühling, Christian (2018). Die europäische Debatte über den Religionskrieg (1679-1714). Konfessionelle Memoria und internationale Politik im Zeitalter Ludwigs XIV. (Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Europäische Geschichte Mainz, 250) Göttingen, Vandenhoeck&Ruprecht, ISBN 9783525310540.

- New, David S. (2013). Holy War: The Rise of Militant Christian, Jewish and Islamic Fundamentalism, McFarland, ISBN 9781476603919.

- Nolan, Cathal J. (2006). The Age of Wars of Religion, 1000–1650: An Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization, Volume 2. London: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 1076. ISBN 978-0313337345.

- Sharma, Vivek Swaroop (March/April 2018) "What Makes a Conflict 'Religious'? in The National Interest 154, 46–55. Full text available at: http://nationalinterest.org/feature/what-makes-conflict-religious-24576.