Hokum

Hokum is a particular song type of American blues music—a song which uses extended analogies or euphemistic terms to make humorous,[1] sexual innuendos. This trope goes back to early dirty blues recordings, enjoyed a huge commercial success in 1920s and 1930s,[1] and is used from time to time in modern American blues and blues rock.

An example of hokum lyrics is this sample from "Meat Balls", by Lil Johnson, recorded about 1937:

Got out late last night, in the rain and sleet

Tryin' to find a butcher that grind my meat

Yes I'm lookin' for a butcher

He must be long and tall

If he want to grind my meat

'Cause I'm wild about my meat balls.

Terminology

"Hokum", originally a vaudeville term used for a simple performance bordering on vulgarity,[2] but hinting at a smart wordplay, was first used to describe the genre of black music in a billing of a race record for Tampa Red's Hokum Jug Band (Tampa Red and Georgia Tom, 1929).[3] After producing a big hit, "It's Tight Like That", with Vocalion Records (and its sequel) in 1928, the musicians went on to Paramount Records where they were called The Hokum Boys. Other recording studios joined the fray using similarly named ensembles.[4] The application of "hokum" to describe the musical approach of these bands was fostered by Papa Charlie Jackson with his "Shake That Thing" (1925).[2]

The term "hokum blues" did not become a formal designation of a style until 1960s.[5] "Hokum" is also used to describe the low comedy acts that were used at the turn of the 20th century to lure audiences to musical performances. In the words of W. C. Handy, a veteran of a minstrel troupe, "Our hokum hooked 'em"[6] outside the opera house, so that "ticket sellers would go to work".[7]

Similar genres

Some of the hokum songs are also classified as belonging to the "dirty blues" subgenre of blues. Some sources treat hokum and dirty (also "bawdy") blues as interchangeable terms.[8][9] However, music researchers point to differences: dirty blues were played before the appearance of hokum,[10] the innuendo in the dirty blues is earnest and mature, while the hokum was full of sass and humor.[11] The dirty blues are good for dancing the slow drag,[11] while hokum, with its bouncy, ragtime-influenced[12] songs is intended for more lively dance style typical for the “mischievous branch” of music[11] (similar to lundu, maxixe, xote, samba).

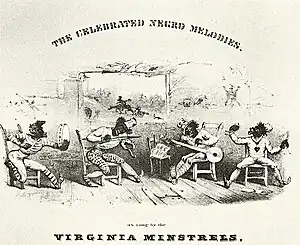

Daniel Beaumont points to minstrel shows, vaudeville, and medicine shows as the origins of humor in blues. These genres influenced the classic and country blues, which in turn fed hokum in the 1930s. Hokum after its heyday influenced rhythm and blues in 1940s and Chicago blues in 1950s and 1960s.[12]

Hokum in early blues

After the First World War, the fledgling record industry split hokum off from its minstrel show or vaudeville context to market it as a musical genre, the hokum blues. Early practitioners surfaced in jug bands performing in the saloons and bordellos of Beale Street, in Memphis, Tennessee. Light-hearted and humorous jug bands like Will Shade's Memphis Jug Band and Gus Cannon's Jug Stompers played good-time, upbeat music on assorted instruments, such as spoons, washboards, fiddles, triangles, harmonicas, and banjos, all anchored by bass notes blown across the mouth of an empty jug. Their blues was rife with popular influences of the time and had none of the grit and plaintive "purity" of blues from the nearby Mississippi Delta. Cannon's classic composition "Walk Right In", originally recorded for Victor in 1930, resurfaced as a number one hit 33 years later, when the Rooftop Singers recorded it during the folk revival in New York's Greenwich Village, and a jug band boom ensued once more.

Hokum blues lyrics specifically poked fun at all manner of sexual practices, preferences, and eroticized domestic arrangements. Compositions such as "Banana in Your Fruit Basket", written by Bo Carter of the Mississippi Sheiks, used thinly veiled allusions, which typically employed food and animals as metaphors in a lusty manner worthy of Chaucer. The hilariously sexy lyric content usually steered clear of subtlety. "Bo Carter was a master of the single entendre", remarked the Piedmont blues guitar master "Bowling Green" John Cephas at Chip Schutte's annual guitar camp. The bottleneck guitarist Tampa Red was accompanied by Thomas A. Dorsey (performing as Barrelhouse Tom or Georgia Tom) playing piano when the two recorded "It's Tight Like That" for the Vocalion label in 1928. The song went over so well that the two bluesmen teamed up and became known as The Hokum Boys. Both previously performed in the band of the "Mother of the Blues", Ma Rainey, who had traveled the vaudeville circuits with the Rabbit Foot Minstrels as a girl, later taking Bessie Smith under her wing. The Hokum Boys recorded over 60 bawdy blues songs by 1932, most of them penned by Dorsey, who later picked up his Bible and became the founding father of black gospel. Dorsey characterized his hokum legacy as "deep moanin', low-down blues, that's all I could say!"

Hokum in early country music

While hokum surfaces in early blues music most frequently, there was some significant crossover culturally. When the Chattanooga-based "brother duet" the Allen Brothers recorded a hit version of "Salty Dog Blues", refashioned as "Bow Wow Blues" in 1927 for Columbia's 15,000-numbered "Old Time" series the label rushed out several new releases to capitalize on their success, but mistakenly issued them on the 14,000 series instead.

In fact, the Allen Brothers were so adept at performing white blues that in 1927, Columbia mistakenly released their "Laughin' and Cryin' Blues" in the "race" series instead of the "old-time" series. (Not seeing the humor in it, the Allens sued and promptly moved to the Victor label.) [13]

An early black string band, the Dallas String Band with Coley Jones, recorded the song "Hokum Blues" on December 8, 1928, in Dallas, Texas, featuring mandolin instrumentation. They have been identified both as proto bluesmen and as an early Texas country band and were likely to have been selling to both black and white audiences. Blind Lemon Jefferson and T-Bone Walker played in the Dallas String Band at various times. Milton Brown and his Musical Brownies, the seminal white Texas swing band, recorded a hokum tune with scat lyrics in the early 1930s, "Garbage Man Blues", which was originally known by the title the jazz composer Luis Russell gave it, "The Call of the Freaks". Bob Wills, who had performed in blackface as a young man, liberally used comic asides, whoops, and jive talk when directing his famous Texas Playboys. The Hoosier Hot Shots, Bob Skyles and the Skyrockets, and other novelty song artists concentrated on the comedic aspects, but for many up-and-coming white country musicians, like Emmett Miller, Clayton McMichen and Jimmie Rodgers, the ribald lyrics were beside the point. Hokum for these white rounders in the South and Southwest was synonymous with jazz, and the "hot" syncopations and blue notes were a naughty pleasure in themselves. The lap steel guitar player Cliff Carlisle, who was half of another "brother duet", is credited with refining the blue yodel song style after Jimmie Rodgers became the first country music superstar by recording over a dozen blue yodels. Carlisle wrote and recorded many hokum tunes and gave them titles such as "Tom Cat Blues", "Shanghai Rooster Yodel" and "That Nasty Swing". He marketed himself as a "hillbilly", a "cowboy", a "Hawaiian" or a "straight" bluesman (meaning presumably, black), depending on the audience for whom he was playing and where he played.

The radio "barn dances" of the 1920s and 1930s interspersed hokum in their variety show broadcasts. The first blackface comedians at the WSM Grand Ole Opry were Lee Roy "Lasses" White and his partner, Lee Davis "Honey" Wilds, starring in the Friday night shows. White was a veteran of several minstrel troupes, including one organized by William George "Honeyboy" Evans and another led by Al G. Field, who also employed Emmett Miller. By 1920, White was leading his own outfit, the All Star Minstrels. Lasses and Honey joined the Grand Ole Opry cast in 1932. When Lasses moved on to Hollywood in 1936 to play the role of a silver-screen cowboy sidekick, Wilds stayed on in Nashville, corking up and playing blues on his ukulele with his new partner Jam-Up (first played by Tom Woods and subsequently by Bunny Biggs). Wilds organized the first Grand Ole Opry–endorsed tent show in 1940. For the next decade, he ran the touring show, with Jam-Up and Honey as the headliners. Pulling a forty-foot trailer behind a four-door Pontiac and followed by eight to ten trucks, Wilds took the tent show from town to town, hurrying back to Nashville on Saturdays for his Opry radio appearances. Many country musicians, like Uncle Dave Macon, Bill Monroe, Eddy Arnold, Stringbean and Roy Acuff, toured with the Wilds tent shows from April through Labor Day. As Wilds's son David said in an interview,

Music was a part of their act, but they were comedians. They would sing comedic songs, a la Homer and Jethro. They would add odd lyrics to existing songs, or write songs that were intended to be comedic. They were out there to come onstage, do five minutes of jokes, sing a song, do five minutes of jokes, sing another song and say, "Thank you, good night", as their segment of the Grand Ole Opry. Almost every country band during that time had some guy who dressed funny, wore a goofy hat, and typically played slide guitar.[14]

Legacy

Although the sexual content of hokum is generally playful by modern standards, early recordings were marginalized for both sexual suggestiveness and "trashy" appeal, but they flourished in niche markets outside the mainstream. "Jim Crow" segregation was still the norm in much of the United States, and racial, ethnic and class bias was embedded in the popular entertainment of the time. Prurience was seen as more antisocial than prejudice. Record companies were more concerned about selling records than stigmatizing artists and minority audiences. Modern audiences might be offended by the packaged exploitation these stock caricatures offered, but in early 20th-century America, it paid for performers to play the fool. Audiences were left on their own to interpret whether they themselves were sharing the joke or were the butts of it. While "race" musicians traded in "coon songs" crafted for commercial consumption by catering to white prejudice. "Hillbilly" musicians were similarly marketed as "rubes" and "hayseeds". Class distinctions bolstered these portrayals of gullible rural folk and witless southerners. Assimilation of African Americans and cultural appropriation of their artistic and cultural creations were not yet equated by the emerging entertainment industry with racism and bigotry.

The eventual success of African-American musical productions on Broadway, like Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle's "Shuffle Along" in 1921, helped to usher in the swing jazz era. This was accompanied by a new sense of sophistication that eventually disdained hokum as backward, insipid, and perhaps most damningly, corny. Audiences began to change their perceptions of authentic "Negro" artistry. White comedians like Frank Tinney and singers like Eddie Cantor (nicknamed Banjo Eyes) continued to work successfully in blackface on Broadway. They even branched out into vaudeville-based sensations like the Ziegfeld Follies and the emerging film industry, but cross-racial comedy became increasingly out of fashion, especially onstage. On the other hand, it is impossible to imagine that the success of comics such as Pigmeat Markham or Damon Wayans or bandleaders like Cab Calloway or Louis Jordan does not owe some debt to hokum. White performers have thoroughly absorbed the lessons of hokum as well, with the "top banana" Harry Steppe, singers like Louis Prima and Leon Redbone or comedian Jeff Foxworthy being prime examples. Offstage it is by no means extinct either, or practiced only by members of one race parodying another race. The Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club, a New Orleans Mardi Gras krewe, has marched on Fat Tuesday since 1900, dressed in raggedy clothes and grass skirts with their faces blackened. Zulu is now the largest predominantly African-American organization marching in the annual Carnival celebration. While the minstrel show, burlesque, vaudeville, variety, and the medicine show have left the scene, hokum is still here.

Rural stereotypes continued to be fair game. Consider the phenomenal success of the syndicated television program Hee Haw, produced from 1969 until 1992. Writer Dale Cockrell has called this a minstrel show in "rube-face". It featured country music stars, curvaceous comedians, and banjo playing bumpkins whose pickin' and grinnin' picked on city slickers and grinned at the buxom All Jugs Band. The rapid fire one-liners, Laugh-In rapid cross-cutting, animations of barnyard animals, hayseed humor and continuous parade of country, bluegrass, and gospel performers appealed to an untapped demographic that was older and more rural than the young, urban "hip" audience broadcasters were routinely cultivating. It is still in syndication today, and is one of the most successful syndicated programs ever. Admirers of hokum warmed to its slyness and the seeming innocence that provided a context for simplistic shenanigans. In the rural south in particular, hokum held on. Cast members like Stringbean and Grandpa Jones were familiar with hokum (and blackface), and if bands named the "Clodhoppers" or the "Cut Ups" and other country cousins of this comedic form are fewer in number today, their presence is still a clue to the country and western, bluegrass, and string band tradition of mixing stage antics, broad parodies and sexual allusions with music.

Examples of hokum

|

|

NB. Various music historians describe many of these songs as dirty blues.

Hokum compilations

- Please Warm My Weiner, Yazoo L-1043 (cover art by Robert Crumb) (1992)

- Hokum: Blues and Rags (1929–1930), Document 5392 (1995)

- Hokum Blues: 1924–1929, Document 5370 (1995)

- Raunchy Business: Hot Nuts & Lollypops, Sony (1991)

- Let Me Squeeze Your Lemon: The Ultimate Rude Blues Collection, (2004)

- Take It Out Too Deep: Rufus & Ben Quillian (Blue Harmony Boys) (1929–30)

- Vintage Sex Songs, Primo 6077 (2008)

Other collections containing hokum

- Traditional Country Music Makers, Vol. 20: Memphis Yodel, Magnet MRCD 020 (Cliff Carlisle and other artists)

- White Country Blues, 1926–1938: A Lighter Shade of Blue, Sony (1993)

- Booze and the Blues, Legacy Roots n' Blues series, Sony (1996)

- Good For What Ails You: Music of the Medicine Shows 1926–1937, Old Hat Records CD-1005 (2005)

References

- Rocha 2022, p. 11.

- Calt 2010, p. 125.

- Larkin 2013.

- Hansen 2000, p. 60.

- Rocha 2022, p. 22.

- Sotiropoulos 2009, p. 40.

- Southern 1972, p. 213.

- DeLune 2015, p. 87.

- Cunningham 2018, p. 78.

- Wald 2010, p. 43.

- Rocha 2022, p. 96.

- Beaumont 2004, p. 476.

- Wolfe, Charles (1998). Entry on the Allen Brothers. The Encyclopedia of Country Music. Paul Kingsbury, ed. Oxford University Press.

- Grant Alden. Interview with David Wilds. No Depression, issue 4, summer 1996.

Sources

- Lott, Eric (1993). Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507832-2.

- Toll, Robert C. (1974). Blacking Up: The Minstrel Show in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-8195-6300-5.

- The Souls of Black Folk by W. E. B. DuBois (Penguin Classics, New York: Penguin Books, reprinted April 1996) ISBN 0-14-018998-X.

- Reminiscing with Sissle and Blake by Robert Kimball and William Bolsom (The Viking Press, New York, 1973)

- Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and Their World by Dale Cockrell (Cambridge University Press, 1997)

- The Story of a Musical Life: An Autobiography by George F. Root (Cincinnati: John Church Co., 1891; reprinted by AMS Press, New York, 1973). ISBN 0-404-07205-4.

- We'll Understand It Better By and By: Pioneering African American Gospel Composers edited by Bernice Johnson Reagon. Wade in the Water Series. (Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C, 1993).

- Black Gospel: An Illustrated History of the Gospel Sound by Vic Broughton (Blandford Press, New York, 1985)

- Where Dead Voices Gather by Nick Tosches, 2001, Little, Brown, Boston. ISBN 0-316-89507-5. On Emmett Miller.

- A Good Natured Riot: The Birth of the Grand Ole Opry by Charles K. Wolfe (Country Music Foundation Press and Vanderbilt University Press, Nashville, Tennessee, 1999)

- Bluegrass Breakdown : The Making of the Old Southern Sound by Robert Cantwell (University of Illinois Press, Chicago, 1984, reprinted 2003).

- It Came from Memphis by Robert Gordon (Pocket Books, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1995).

- Stephen Foster: America's Troubadour by John Tasker Howard. (Thomas Y. Crowell, New York, 1934; 2nd ed., 1953)

- The Encyclopedia of Country Music edited by Paul Kingsbury (Oxford University Press, New York, 1998)

- Minstrel Banjo Style various artists, liner notes, Rounder Records ROUN0321, 1994

- You Ain't Talkin' to Me: Charlie Poole and the Roots of Country Music liner notes by Henry Sapoznik, Columbia Legacy Recordings C3K 92780, 2005

- Good for What Ails You: Music of the Medicine Shows 1926–1937 liner notes by Marshall Wyatt, Old Hat Records CD-1005 (2005)

- Rocha, Alexandre Eleutério (2022). Hokum Blues: erotismo e humor em uma vertente musical silenciada (PDF) (Mestre em Música thesis) (in Portuguese). Universidade de Brasília.

- DeLune, Clair (21 September 2015). South Carolina Blues. Arcadia Publishing. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4396-5327-2. OCLC 936538023.

hokum, which is also called "bawdy" or "dirty" blues

- Wald, Elijah (3 August 2010). The Blues: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-19-975079-5. OCLC 1014220088.

flood of hokum songs established blues as a medium for [...] comic smut. There had always been dirty blues [...]

- Cunningham, Alexandria (2018). "Make It Nasty: Black Women's Sexual Anthems and the Evolution of the Erotic Stage". Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships. 5 (1): 63–89. doi:10.1353/bsr.2018.0015. eISSN 2376-7510.

(page 78): dirty blues was a subgenre [...] also referenced as hokum

- Calt, Stephen (1 October 2010). Barrelhouse Words: A Blues Dialect Dictionary. University of Illinois Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-252-09071-4. OCLC 1156337352.

hokum: A vaudeville term [...] fun bordering on vulgarity and quite obvious [...] descriptive of material by [...] Hokum Boys [...] musical approach [...] fostered by Papa Charlie Jackson

- Larkin, Colin (30 September 2013). The Virgin Encyclopedia of The Blues. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4481-3274-4.

'Hokum, with its connotations of verbal cleverness, was first applied to black music [...] in billing of 'Tampa Red's Hokum Jazz Band' [ Tampa Red and Georgia Tom ]

- Hansen, Barry (2000). "A Lot of Hokum". Rhino's Cruise Through the Blues. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-87930-625-0. OCLC 39007030.

- Beaumont, Daniel (2004). "Humor". In Komara, E.; Lee, P. (eds.). The Blues Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 476–479. ISBN 978-1-135-95832-9. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- Southern, Eileen (1972). Readings in Black American Music. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-02165-3. Retrieved 2023-06-27.

- Sotiropoulos, Karen (2009). Staging Race: Black Performers in Turn of the Century America. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04387-9. Retrieved 2023-06-27.

- Schwartz, Roberta Freund (2018-10-01). "How Blue Can You Get? "It's Tight Like That" and the Hokum Blues". American Music. University of Illinois Press. 36 (3): 367–393. doi:10.5406/americanmusic.36.3.0367. ISSN 0734-4392.