History of the Jews in Laupheim

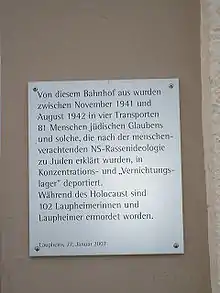

The history of the Jews in Laupheim began in the first half of the 18th century. Until the second half of the 19th century, the Jewish community in Laupheim, expanded continuously to become the largest of its kind in Württemberg.[1] During this period, the Jewish community gradually assimilated to its Christian surroundings and its members prospered until the beginning of the Nazi-period in 1933. With the deportation of the last remaining Jews in 1942, more than 200 years of Jewish history in Laupheim forcibly came to an end.[2]

Prelude

At the beginning of the 18th century, Laupheim was a small market town in Upper Swabia and politically part of Further Austria. Jews were allowed to enter the town as pedlars but permanent residence was refused. Since the 15th century, Jews were not allowed to settle within the territories of the surrounding free imperial cities, nor in the Duchy of Württemberg.[3] The settlement of Jews in the territories of Imperial Knights, however, was often welcomed. These rulers were often highly in debt due to the fragmentation of their territories, as was the case with Laupheim being separated into two independent states, Großlaupheim and Kleinlaupheim, as well as frequent wars. The income generated by taxation of the Jews helped to sustain the life-style of the nobility and also to stimulate the local economy.

Hans Pankraz von Freyberg, the ruler of Laupheim between 1570 and 1582, explicitly forbade his subjects any contact with Jews[4] and another early local law from 1622 threatened any inhabitant of Laupheim, who got involved with Jews with a fine of 25 fl.[5] However, by then several Jewish communities had already been established in Upper Swabia. The local ruler of the nearby village of Baltringen allowed Jews to settle there in 1572. In the villages of Schwendi and Orsenhausen, the last of which still has a Judengasse ("Jews' Lane"), Jewish communities seem to have existed well before the 18th century. In Laupheim, the presence of Jewish traders on market days in the 17th century is documented.[6] Yet, permanent Jewish presence in Laupheim was not permitted until the 18th century.

From the beginnings until the Jews' Act of 1828

In 1724, Abraham Kissendorfer from Illeraichheim petitioned the owner of Großlaupheim, Constantin Adolf von Welden, and the owner of Kleinlaupheim, Damian Carl von Welden, to allow three Jewish families, later extended to twenty, to settle in Laupheim. After some negotiation, an agreement was reached and permission for a permanent Jewish presence was granted so that four Jewish families entered Laupheim: Leopold Jakob, Josef Schlesinger and Leopold Weil from Buchau, and David Obernauer from Grundsheim.[7] The first protection contract between them and the local authorities dates from 1730 which indicates that the final arrival of the four Jewish families occurred in that year. This contract was at first limited to 20 years. The first house for the newly arrived Jews was erected between 1730 and 1731. The Jews had to contribute to the costs of the house with 100 fl each.[8]

Various taxes, financial obligations and restrictions were imposed on the Jews: a special death duty as well as compensation for various services the local serfs were obliged to perform and from which the Jews were exempt, had to be paid; an extra tax per capita was also imposed by Austrian officials.[9] Furthermore, Jews had to wear special garment and hats and were allowed to trade in any goods except those that were considered to be of suspicious or dubious origin, such as wet cloth, unthreshed grain and untanned hide, as well as goods that had a particular Christian, liturgical character.[10] Transactions of more than 4 fl had to be registered with the local authorities. The slaughter of animals according to Jewish rites and the selling of the meat itself were allowed. However, the tongue of each slaughtered cow as well as the innards of calves and sheep slaughtered according to Jewish rites had to be handed over to the authorities. Alternatively, 4 kr could be paid for each slaughtered animal. Jews were not allowed to buy and own property and to prevent any of their community from converting to Christianity. On the other hand, they were strictly forbidden to convert any Christians to Judaism.[11]

In the years after 1730, more Jewish families came to Laupheim from Fellheim, Fischach, Illeraichheim[12] and other places, where Jews had already been allowed to settle, so that, when, in 1754, the protection contract, which had expired some time before,[13] was renewed for another 30 years, the Jewish community in Laupheim had grown to 27 families. The contract was again renewed in 1784 and with each of these renewals a substantial fee of 800 fl had to be paid. The families arriving after 1750 had to have their houses built at their own expense. The area where those dwellings were built was allocated by the local rulers, who also kept the legal right to the properties. After 1784, these houses were held by the Jews as hereditary fiefs from the local rulers.[10]

A plot of uncultivated land to the north of the Jewish settlement in Laupheim was bought by the infant community shortly after their settlement to be used as a cemetery. Due to the rapid growth of the population the cemetery had to be expanded in 1784, 1856 and again 1877.[14]

Once the quorum of ten or more adult male Jews was reached, (Minyan), the first Jews in Laupheim used a room on the first floor in the house of butcher Michael Laupheimer, located on the Judengasse, for their religious services.[15] However, the continuous, rapid growth of the Jewish community made it necessary to have a synagogue built. It was built as an L-shaped building next to the cemetery close to the spot where later on the Jewish mortuary was to be built.[16]

Unlike the unfree Christian population of both parts of Laupheim, the Jewish inhabitants had a considerable larger autonomy in administrating their own communal affairs. Around 1760, a Jewish community seems to have been officially established with the permission to elect two parnassim, chairmen of the community, one for each part of the divided Laupheim, as the town had been separated into Großlaupheim and Kleinlaupheim since 1621. The parnassim were allowed to make independent decision concerning the internal affairs of the Jewish community. Other tasks included the appointment of the rabbi and the chazzan.[17] These officials were not included in the number of Schutzjuden ("Protected Jews") and were exempt from the annual protection fee the other Jewish inhabitants of Laupheim had to pay. The Jewish community as a whole had to pay the fees for the parnassim and it also had to provide for their accommodation. The parnassim and the rabbi had restricted legal authority over members of the community, being permitted to exact, up to a certain amount, financial penalties.[18] In cases they were not allowed to decide, respected non-local rabbis were consulted and in very important legal disputes, the files were sent for consultation to the Jewish communities in Frankfurt, Fürth or even as far as Prague.[9] In criminal cases and in disputes between Christians and Jews, the local ruler reserved the right to make a legal decision.

The settlement of the Jews in Laupheim developed on the so-called Judenberg ("Jews’ mountain" or rather "Jews’ hill") with the Judengasse ("Jews’ Lane") at its centre, a ghetto-like area, separated from the rest of the town, yet in close proximity to the market square. The Judenberg forms a regular square where the 8 oldest houses, arranged in 3 rows, are positioned parallel to one of the main streets leading away from the town centre.[10] The local Jews were allowed to influence the planning and design of their houses from the end of the 18th century onwards. It is remarkable, even today, that all houses are approachable from the front as well as the back, and that even the front yards and front gardens are not fenced in. The reason for this lies in the fact that the Judengasse was meant to incorporate the whole Jewish settlement to form an eruv.[19]

After having received the houses as hereditary fiefs in 1784, Jews were allowed to buy their houses from 1812 onwards. In 1807, 41 families lived in 17 houses on the Judenberg. In 1820, the number had risen to 59 families living in 34 houses.[20]

This growth in population made it necessary in 1822, to have an even bigger synagogue built. The new building was erected at a cost of 16.000 fl. However, due to errors made during the construction, the building had to be completely broken down less than 15 years later, to be replaced by a new building in 1836/1837. This new synagogue had a length of approximately 24 metres and was approximately 13 metres wide.[21]

From 1828 to 1869

In 1806, both parts of Laupheim were annexed by the newly formed Kingdom of Württemberg. As a consequence the Jews in Laupheim now fell under the jurisdiction of Württemberg. Initially, there were no changes in the legal status of Jews living within the kingdom.[22] However, the Jews’ Act of 1828 meant a considerable improvement in the status of the Jews. The legal obligation of Jews living only in the areas allocated by the authorities was lifted. Jews now had the freedom to settle and live wherever they decided to. The effect of this law in Laupheim meant that very soon the Jewish population had houses built along the Kapellenstraße and the surrounding areas so that the street unofficially received the name of Judenstraße ("Jews' Street").[23] The fact that in a relative short period of time so many new buildings could be erected is an indication of the prosperity of the Jewish community, particularly regarding the recession and the famines that followed the Napoleonic Wars. Another indication for this prosperity was the fact that, when a couple wanted to get married, it had to prove a certain amount of wealth before the permission to marry was granted by the local ruler, more Jewish inhabitants of Laupheim were able to get married than their Christian fellow-citizens. The act of 1828 also lifted any restrictions with regards to the prohibition of Jews to choose their professions. From now on, Jews were allowed to choose and work in any profession they wished. Furthermore, the prohibition of Jews to buy and own property was abolished.[24]

In the years following this decree, Jews from Laupheim bought several bankrupt agricultural businesses in the surrounding villages as well as within the town of Laupheim itself, split them into smaller entities and sold them off again, thereby making considerable profit. One example of this is the acquisition of Großlaupheim Castle with all its property by the family Steiner in 1843. In 1840, Karl von Welden, the last feudal lord of Laupheim, sold the castle to the state of Württemberg. He was bitterly disappointed with his subjects obstinate behaviour towards him as their former feudal lord (they had taken him to court for 300 different offences) and sold the castles to the Kingdom of Württemberg.[25] Großlaupheim Castle with all accompanying lands was then acquired by the Jewish merchant Viktor Steiner[26] whose family managed to hold on to the possession for five generations, even through the Nazi-period, until 1961. After Viktor Steiner's death in 1865, his son, Daniel Steiner, and his son-in-law, Salomon Klein, became heirs to the business. They, in turn, sold it on to Laupheim-born banker and industrialist Kilian Steiner, who had resided in Stuttgart.[27]

The government's policy to encourage young Jews to learn one of the crafts they had been excluded from, only met with partial success. Even though more Jews became apprentices to craftsmen, they usually chose a profession which later enabled them to change it into a craft-related trade.[28]

A side effect of the act was that those Jews who had not used a surname as yet were forced to acquire family names. Few of the Laupheim Jews had had surnames. Those that had used them were the families of Einstein, Obernauer and Weil. Suddenly new families seemed to emerge even though they had been living in Laupheim for quite some time. There were several options: one, to Germanise the first name, which led, amongst others, to Levi, Löw, Löffler and Levinger, instead of Levi, or to Heumann instead of Hayum. A second option was to use the name of the place from where the family had once moved to Laupheim. This resulted in family names such as Nördlinger, Öttinger, Hofheimer and Thannhauser. Furthermore, not only surnames were suddenly Germanised but first names were adapted to the German speaking environment too. Hayum became, for example, Heinrich, Baruch was changed to Berthold or Bernhard, so that at the end of the 19th century, it was almost impossible to distinguish the Jewish citizens of Laupheim from their Christian fellow-citizens simply because of their names.[29]

The Jews' Act of 1828 forced the rabbis to keep vital records of all members of their community, something Christian priests had been obliged to do so for a long time. Rabbis now had to keep records of all birth certificates, marriage licenses, and death certificates. This turned the office of rabbi from being a purely spiritual leader into a semi-official function, the tasks of which also included administration for which he was accountable to the officials of the Kingdom of Württemberg.[30]

The economic equality granted to the Jews in 1828 caused an increase in building works in Laupheim which, in turn, caused an increase in the economic fortunes of the small market town. This is demonstrated by the fact that the number of building-related craftsmen doubled within ten years between 1845 and 1856. The weekly market, which had been discontinued at the beginning of the century, was reintroduced in 1842. Although it had to compete with the larger markets in Ulm and Biberach, it still managed to hold its own as many horse and cattle traders as well as pedlars and hawkers, quite a few of whom were Jewish, visited the market in Laupheim, further contributing to its prosperity.[31] Also, a great number of the founders of the local trade bank, an early form of the Credit Union, in 1868, were Jewish entrepreneurs from Laupheim.[32] Until 1933 they were to partake in its development in prominent positions.

In 1864, Jews living in the Kingdom of Württemberg, were finally granted complete political equality.[33] This meant that after achieving economic emancipation, they were now citizens with the same rights and obligations as their Christian neighbours. Soon after this, in 1868, the first Jewish counsellors appeared on the town council, Samuel Lämmle being the first Jew elected to it.[31]

From 1869 to 1933

The Laupheim Jews contributed substantially to the effort to have Laupheim elevated to the status of city, by appealing repeatedly to the King of Württemberg to grant Laupheim this status from the early years of the 1860s onwards. Finally, in a charter of 1869, the King of Württemberg conferred on Laupheim city rights.

Ironically, the absolute number of Jewish inhabitants in Laupheim reached its zenith the very same year. In 1856, the number of Jewish inhabitants constituted more than a fifth of all inhabitants of Laupheim, even though the absolute number was less than in 1869. This is because the general population of Laupheim grew disproportionally. In 1869, 843 Jews were registered in Laupheim, accounting for approximately twelve percent of the total population. From this year onwards, the Jewish population dwindled. The reason for this lies in the fact that for many Jewish inhabitants, Laupheim did not offer enough opportunities to sustain a living. This process of migration had already started in the 1850s with many Laupheim Jews being attracted to the bigger cities, such as Ulm, Stuttgart, Munich and Frankfurt. Furthermore, between 1835 and 1870, no less than 176 Jewish inhabitants of Laupheim emigrated to the United States, particularly after the failed revolution of 1848 and its ensuing economic crisis, which was felt most harshly by those who were less affluent. Some did return but most stayed and became an integral part of the United States. This development gathered momentum in the 1870s with more and more Jewish inhabitants leaving Laupheim either to move abroad or to other centres within the newly founded German Empire.[34] In 1871 the Emancipation Law was passed and applied to all of Germany. As equal citizens the Jews began to reap success in all walks of life. Over 60% of them belonged to the settled middle-class.[35]

The upturn in Jewish fortunes was also shown in the fact that the community could afford to have the synagogue completely rebuilt and refurbished. As early as 1845 there had been complaints that the synagogue was too small to accommodate the growing numbers of believers. The works for the new synagogue finished in May 1877. By adding two towers with domed roofs and wide, rounded windows, the building was given a renaissance-like appearance.[36]

During this period, several businesses were founded or expanded. A company producing wooden tools, founded by Josef Steiner and his four sons, became one of the leading distributors of products of this kind in southern Germany. A company for refinement of hair products was founded by the brothers Bergmann. This company still exists today, having been Aryanised after 1933, only to be given back to its rightful owners after 1945, and is now operating worldwide. A textile mill was established by Emmanuel Heumann, continued by his sons, in the town centre. The premises were later moved to the suburbs. The hop merchant Steiner also began in Laupheim to become one of the leading players in this market after expanding into the United States. The headquarters of this company are now in New York City. Until the 1880s, trading in real estate was in Jewish hands but this vanished completely after the establishing of the credit union. The local dealers in livestock, however, were until after 1933 predominantly Jewish as well as the traders in liquor, wine, oil, grain and timber. There were even a few private banks owned by Jews, which were successful enough to survive well into the 1930s but were forced to close down after 1933 following the immense pressure put on them by the National Socialist administration.

Around and in the vicinity of the market square, several retail shops were established, specializing in selling textile products. The first department store in Laupheim was erected in 1906 by Jewish merchant Daniel David Einstein whose family had been residents of Laupheim since the second half of the 17th century. Until the late 1980s, it was still possible to see the by then faded name of the original owner above the entrance. A number of public houses were also run by Jewish landlords. Less remarkable and yet important are the contributions made by local Jewish craftsmen. There were several bakers and butchers, serving the Jewish as well as the Christian inhabitants of Laupheim. Also, a number of Jewish cobblers, furriers, clockmakers, tailors and wood turners had their shops near the market square.[37]

By the end of the 19th century Jews in Laupheim were completely integrated and assimilated into society, being part of all walks of life, a situation which would not change for more than 30 years. This assimilation is seen by the fact that many, more affluent Jews moved away from the confinement of the Judenberg. Consequently, many of the Gründerzeit buildings still existing in Laupheim were erected by Jews.[38]

The Jewish school

Traditionally, the education of the children of a Jewish family rested with the father. However, the absence of many fathers due to their frequently being away from home in their capacity as traders, made it necessary to employ travelling teachers who received food and accommodation in return for their services. These teachers, called chedarim, received a contract of six months, usually terminating at either Pesach or Sukkot.[16] In 1808, the number of Jewish children amounted to 39 which indicates that many children were sent to either Christian schools or to Jewish schools outside Laupheim. The first Jewish school was founded only in 1823, when the Jewish community rented a ballroom in a public house to be used as a classroom and hired a teacher, Simon Tannenbaum from Mergentheim. He acted as head teacher until his retirement in 1860.[39] As his assistant Abraham Sänger from Buttenhausen was taken on and worked as teacher until his death in 1856.[40] His descendants run the public house Zum Ochsen until after 1933. In 1830, the Jewish community bought a house opposite the synagogue which was refurbished to house the rabbi's office and the school. This building functioned as school until 1868 when a new Jewish school was built in the vicinity of the Judenberg in the Radgasse. This building was demolished in 1969.[16] Due to the lack of Jewish teachers, for several years Roman Catholic teachers were asked to help out.[41] In 1874, 162 Jewish pupils attended the Jewish school. In the following decades, the number of Jewish pupils would decrease continuously, so that, at the beginning of the 20th century, the Jewish school taught only 65 pupils. However, the Jewish school existed until well into the 1930s and was only closed in 1939.

Jewish societies

The first Jewish society (Chewra Kadischah) was founded in 1748 with the task of looking after the ill and taking care of funerals. This society was active for almost 200 years. In 1780, the Talmud-Torah-Society was founded to assist the religious instruction of fellow Jews and to take care of young people. It was accompanied by a welfare society Nathan Basseser, founded in 1804, the Jewish Women Society and the Jewish Orphan Fund, supporting the Jewish orphanage in Esslingen, in 1838. Jewish societies sprang up not only for charitable but also for sociable purposes. A choral society, called Frohsinn (Cheerfulness), was founded in 1845 and went on to win many prizes at choir festivals. The reading society Konkordia (Concord) came into existence in 1846 on the initiative of the Laupheim-born rabbi-candidate Max Sänger.[42]

From 1933 to 1938

After the appointment of Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933 and the subsequent seizure of power by his party, the National Socialist German Workers Party, Jewish life in Laupheim began to change for the worse. During the previous decades, Jews had been influential and prominent members in all ways of life, not only in the economic life but also in the cultural sphere. Numerous non-Jews had been employed by Jewish-run businesses and by Jewish households. Jews had been participating in all spheres of public and commercial life. The local craftsmen had been able to rely on Jewish customers to sell their products to. Jews were members in several cultural, political and social societies. All these relations began to loosen or even abruptly break down after January 1933. On 1 April 1933, the nationwide Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses, organised by Julius Streicher, also took place in Laupheim. Members of the local SA positioned themselves in front of Jewish shops in order to intimidate potential customers and prevent them from entering. The windows of one shop were smashed.[43] In the year following the Nazis' rise to power, in the course of so-called Gleichschaltung, the Laupheim Jews were deprived of membership of all non-Jewish organisations, be it political or cultural. On 6 November 1935, a non-local party group leader of the NSDAP took photographs of customers entering a shoe shop, which happened to be owned by a Jew. This caused such a commotion that the police had to be called in to disperse the crowd, which was shouting abuse at entering customers by calling them Volksverräter (people's traitors) and Judenknecht (Jews' servant).[44][45] The propaganda of the ruling party had its effects in that the turnover of Jewish businesses decreased dramatically; one shop's revenue declined even by 80 percent. Many customers went for their purchases to Ulm and Biberach instead. The Nuremberg Laws of 1935, reduced the Jews in Germany to the status of second class citizens and prohibited the Jews to employ female Aryans under the age of 45. On 8 April 1938, the Jewish cattle traders were allocated a separate part on the weekly cattle market and as of 1 January 1939 the licences for Jewish cattle trader were permanently revoked. From June onwards, all Jewish businesses had to be visibly marked. In July, Jewish physicians were struck off the medical register. In September, the permission of Jewish members of the legal profession to practice law was cancelled. There were further restrictions and harassment in the same year such as the adding of Sara and Israel respectively to non-Jewish first names, the confiscating and re-issuing of passports after a large J was added. However, many Jews clung to the businesses their ancestors had established and hoped that by keeping a low profile they could weather the storm. A record from July 1938, shows that there still existed 45 businesses run by Jews in Laupheim.[46]

The assassination of Ernst vom Rath, Third Secretary of the German Embassy in Paris, by Herschel Grynszpan served as a pretext for a nationwide pogrom against Jews throughout Germany and Austria on the night of 9–10 November 1938, colloquially known as Kristallnacht. In Laupheim, Jewish shops were vandalised and the synagogue was burnt to the ground. The fire-brigade was prevented by locals from extinguishing the fire. A number of Jewish inhabitants were arrested and transported to the town hall. From there, they were marched to the burning synagogue, escorted by members of the Nazi-party, where they had to listen to a diatribe by a SA-leader, after which they were forced to carry out physical exercises in front of the burning building during which several of them were physically assaulted and injured.[47] Afterwards, some of them were released, whereas the more prominent Jews were transported to the concentration camp Dachau. One, Sigmund Laupheimer, was beaten to death by SS guards during his confinement there.[48] By February 1939 16 of the imprisoned men had been released.[49] The main perpetrators, were never brought to justice as they were either killed during the war or missing in action. 16 locals, however, were tried in 1948. All of them claimed that they were acting under orders. Four of them were acquitted whereas the twelve others were sentenced to prison terms ranging between two months and one year for crimes against humanity and being accessory to arson.[50]

The end of Jewish life in Laupheim

A few days after the pogrom of 9–10 November 1938, a decree for the expropriation of Jewish businesses was implemented. Following this, all Jewish businesses had to be Aryanised. In Laupheim this meant that some Jewish shops were bought by one or some of the former employees at a rate considerably lower than the current market price.[51] However, most of these businesses did not manage to survive for long as they lacked sufficient capital and expertise to run an enterprise, especially since there was no possibility to export goods.

As a result of the accelerated discrimination of Jews, emigration from Laupheim increased to 32 in 1939. In 1940, only 14 persons managed to escape the oppression and in 1941 a meagre 4 Jews from Laupheim managed to leave the country.[52] Those remaining were, after having been driven out of business, systematically deprived of their other properties, evicted and allocated alternative accommodation. Some were moved into the former Rabbi's office building, now turned into a Jewish retirement home, where living conditions were very crammed. Others were sent to live in the Wendelinsgrube, a designated settlement area in a gravel pit just outside the then built-up area of Laupheim, where since 1927 small houses had been erected to provide accommodation for the unemployed and homeless. By 1939 these houses consisted of wooden shacks without running water or electricity. The former residents of the Wendelinsgrube moved into the forcibly abandoned Jewish properties.[53] On 28 November 1941, the first transport of Laupheim Jews left, in the first instance to Stuttgart, and then onwards to Riga. The second wave of deportations took place on 25 March 1942, when a number of Laupheim Jews were transported to the General Government, Poland. The final deportation took place on 19 August 1942, when the remaining 43 Jews of Laupheim, amongst whom were all the remaining inhabitants of the Wendelinsgrube, were transported to the east to the concentration camp Theresienstadt.[49] This date marks the end of more than 200 years of Jewish history in Laupheim since none of the emigrants or surviving deportees returned to live in Laupheim.

Development of the Jewish population in Laupheim

The table below shows the development of the Jewish population of Laupheim and also shows these numbers in relation to the total number of inhabitants of Laupheim.[54]

| Year | Jewish population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1730 | ca. 25 | 1.3% |

| 1754 | ca. 75 | 3.7% |

| 1784 | ca. 125 | 5.6% |

| 1808 | 278 | 8.6% |

| 1824 | 464 | 17.3% |

| 1831 | 548 | 18.2% |

| 1846 | 759 | 21.7% |

| 1856 | 796 | 22,6% |

| 1869 | 843 | 13.4% |

| 1886 | 570 | 8.3% |

| 1900 | 443 | 6.1% |

| 1910 | 348 | 4.3% |

| 1933 | 249 | 2.7% |

| 1943 | 0 | 0,0% |

Of the 249 Jews registered in Laupheim in 1933, 126 managed to save their lives by fleeing Germany and emigrating to various foreign destinations.[55]

Rabbis of the Laupheim Jewish community

A complete list of all the Laupheim rabbis does not exist. The first rabbi is mentioned in 1730 but there is a gap in the records until 1760.[56]

| Year | Name | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1730 – ? | Jakob Bär (Beer) | from Fellheim near Memmingen |

| 1760–1804 | Maier Lämmle | (? - 1804 in Laupheim)[57][58] |

| 1804–1824 | David Levi | (? in Schnaitheim, now part of the city of Heidenheim – 1824 in Laupheim)[59] |

| 1824–1825 | Leopold Lehmann | substitute for one year before being called to Belfort |

| 1825–1835 | Salomon Wassermann | (1780 in Oberdorf – 1859 in Laupheim) previously rabbi in Ansbach, later rabbi in Bad Mergentheim until 1854[60] |

| 1835–1852 | Jakob Kaufmann | (1783 in Berlichingen – 1853 in Laupheim) previously rabbi in Weikersheim and Bad Buchau[61] |

| 1852–1876 | Dr Abraham Wälder | (1809 in Rexingen – 1876 in Laupheim) previously rabbi in Berlichingen[62] |

| 1877–1892 | Dr Ludwig Kahn | (1845 in Baisingen – 1914 in Heidelberg) afterwards rabbi in Heilbronn until 1914[63] |

| 1892–1894 | Dr Berthold Einstein | (1862 in Ulm – 1935 in Landau) afterwards rabbi in Landau until 1934[64] |

| 1895–1922 | Dr Leopold Treitel[65] | (1845 in Breslau – 1931 in Laupheim) previously rabbi in Karlsruhe; Jewish scholar |

Following the retirement of Leopold Treitel, the Laupheim rabbinate ceased to exist on 1 April 1923.[66]

Prominent Jews from Laupheim

- Kilian von Steiner (9 October 1833 – 11 November 1903), banker.

- Moritz Henle (7 August 1850 – 24 August 1925), cantor and composer of Jewish reform movement.

- Carl Laemmle (17 January 1867 – 24 September 1939), film producer, founder of Universal Studios.

- Friedrich Adler (29 April 1878–1942), Jugendstil and Art Deco designer; murdered in Auschwitz.

- Hertha Nathorff (5 June 1895 – 10 June 1993), pediatrician.

- Gretel Bergmann (12 April 1914 – 25 July 2017), internationally renowned high jumper of the 1930s.

- Siegfried Einstein (30 November 1919 – 25 April 1983 in Mannheim), author and poet.

See also

Notes

- P. Sauer, Die jüdischen Gemeinden in Württemberg und Hohenzollern, p. 118

- W. Eckert, "Zur Geschichte der Juden in Laupheim", p. 62

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 4

- J. A. Aich, Laupheim 1570–1870, p. 7

- G. Schenk (a), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 103

- G. Schenk (b), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 286

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 7f

- S. Kullen, "Spurensuche", p. 46

- G. Schenk (a), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 104

- L. Georg, Historische Bauten, p. 57

- S. Kullen, "Spurensuche", p. 47

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 11

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 18

- S. Kullen, "Spurensuche", p. 52

- G. Schenk (b), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 295

- S. Kullen, "Spurensuche", p. 51

- G. Schenk (b), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 288

- L. Georg, Historische Bauten, p. 59

- G. Schenk (b), "Die Juden in Laupheim Laupheim", p. 289

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 30ff

- G. Schenk (a), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 113

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 45

- S. Kullen, "Spurensuche", p. 50

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 47f

- G. Schenk (b), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 290

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 73

- Benigna Schönhagen, Kilian und Steiner und Laupheim, p. 4, 11f

- G. Schenk (b), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 290f

- G. Schenk (b), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 291

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 51

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 48

- S. Kullen, Spurensuche, p. 47

- H. Engisch, Das Königreich Württemberg, p. 82

- G. Schenk (b), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 292f

- "The Jews of Germany". Beit Hatfutsot Open Databases Project, The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot.

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 53ff

- G. Schenk (b), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 298

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 49

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 57

- L. Georg, Historische Bauten, p. 61

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 58

- G. Schenk (b), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 298; W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 58ff

- W. Eckert, "Zur Geschichte der Juden in Laupheim", p. 59. This was the department store D. M. Einstein, owned by the father of poet Siegfried Einstein.

- G. Schenk (b), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 299

- A. Köhlerschmidt & Karl Neidlinger, Die jüdische Gemeinde Laupheim und ihre Zerstörung, p. 298

- S. Kullen, "Spurensuche", p. 49

- W. Eckert, "Zur Geschichte der Juden in Laupheim", p. 60

- Ray, Roland (9 November 2013), ""Herr Lehrer, Ihre Kirche brennt!"", Schwäbische Zeitung (in German), retrieved 26 January 2020

- G. Schenk (b), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 300

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 79ff; G. Schenk (a), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 118

- W. Eckert, "Zur Geschichte der Juden in Laupheim", p. 61

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 85

- A. Köhlerschmidt & Karl Neidlinger, Die jüdische Gemeinde Laupheim und ihre Zerstörung, p. 357

- Statistisches Landesamt Baden-Württemberg ; G. Schenk (b), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 215, 239, 292, 450; J. A. Aich, Laupheim 1570–1870, p. 31

- Hecht, Cornelia. "Museum zur Geschichte von Christen und Juden – Laupheim" (PDF) (in German). Landeszentrale für politische Bildung. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 51f.

- Säbel, Heinz (1937-05-30). "Hundert Jahre Synagoge Laupheim". Hertha Nathorff Collection; AR 5207; box number 1; folder number 3; Leo Baeck Institute. Center for Jewish History. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- Wilke, Carsten, ed. (1996). "Lämmle, Maier". Biographisches Handbuch der Rabbiner 1. Die Rabbiner der Emanzipationszeit in den deutschen, böhmischen und großpolnischen Ländern 1781–1871 (in German). München: De Gruyter Saur. p. 584. ISBN 3-598-24871-7.

- Wilke, Carsten, ed. (1996). "Levi, David". Biographisches Handbuch der Rabbiner 1. Die Rabbiner der Emanzipationszeit in den deutschen, böhmischen und großpolnischen Ländern 1781–1871 (in German). München: De Gruyter Saur. p. 557. ISBN 3-598-24871-7.

- Wilke, Carsten, ed. (1996). "Wassermann, Salomon". Biographisches Handbuch der Rabbiner 1. Die Rabbiner der Emanzipationszeit in den deutschen, böhmischen und großpolnischen Ländern 1781–1871 (in German). München: De Gruyter Saur. p. 880. ISBN 3-598-24871-7.

- Wilke, Carsten, ed. (1996). "Kaufman, Jakob". Biographisches Handbuch der Rabbiner 1. Die Rabbiner der Emanzipationszeit in den deutschen, böhmischen und großpolnischen Ländern 1781–1871 (in German). München: De Gruyter Saur. p. 520f. ISBN 3-598-24871-7.

- Wilke, Carsten, ed. (1996). "Wälder, Abraham". Biographisches Handbuch der Rabbiner 1. Die Rabbiner der Emanzipationszeit in den deutschen, böhmischen und großpolnischen Ländern 1781–1871 (in German). München: De Gruyter Saur. p. 874. ISBN 3-598-24871-7.

- Wilke, Carsten, ed. (1996). "Kahn, Ludwig". Biographisches Handbuch der Rabbiner 1. Die Rabbiner der Emanzipationszeit in den deutschen, böhmischen und großpolnischen Ländern 1781–1871 (in German). München: De Gruyter Saur. p. 502. ISBN 3-598-24871-7.

- Jansen, Katrin Nele; Brooke, Michael; Carlebach, Julius, eds. (1996). "Einstein, Berthold". Biographisches Handbuch der Rabbiner 2. Die Rabbiner im Deutschen Reich 1871–1945 (in German). Vol. 2. München: De Gruyter Saur. p. 174. ISBN 978-3-598-24874-0.

- G. Schenk (a), "Die Juden in Laupheim", p. 113f; W. Kohl, Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim, p. 52; R. Emmerich, "Philo und die Synagoge", p. 13; A. Köhlerschmidt & K. Neildinger (Hrsg.), Die jüdische Gemeinde Laupheim und ihre Zerstörung, p. 524; H. Säbel, "Hundert Jahre Synagoge Laupheim", p. 3, in: Hertha Nathorff Collection, 1813–1967. Schenk dates Treitel's rabbinate from 1895 to 1925 whereas Kohl says that with the retirement of Treitel on 1 April 1923, the office of rabbi in Laupheim ceased to exist. This is confirmed by Emmerich who indicates that Treitel was rabbi for more than 28 years and retired in the year of the publication of his monograph on Philo of Alexandria in 1923. However, during a speech held in 1937 the last teacher of the Laupheim Jewish school, Heinz Säbel, dated the end of Treitel's rabbinate to 1922. Furthermore, in an obituary dated 20 March 1931 published in the C.V.-Zeitung, the weekly newspaper of the Central-Vereins deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens, upon the death of Treitel the dates for his rabbinate are given as 1985 to 1922.

- A. Hoffmann, Schnittmengen und Scheidelinien, p. 12

Further reading

- Adams, Myrah; Schönhagen, Benigna (1998). Jüdisches Laupheim. Ein Gang durch die Stadt. Haigerloch: Medien und Dialog. ISBN 3-933231-01-9.

- Aich, Johann Albert (1921). Laupheim 1570–1870. Beiträge zu Schwabens und Vorderösterreichs Geschichte und Heimatkunde (4th ed.). Laupheim: A. Klaiber.

- Eckert, Wolfgang (1988). "Zur Geschichte der Juden in Laupheim". Heimatkundliche Blätter für den Kreis Biberach. 11 (2): 57–62.

- Emmerich, Rolf (1998). "Philo und die Synagoge – Dr. Leopold Treitel, der letzte Rabbiner von Laupheim". Schwäbische Heimat (4): 13–19.

- Engisch, Helmut (2006). Das Königreich Württemberg. Stuttgart: Theiss. ISBN 978-3-8062-1554-0.

- Georg, Lutz (1967). "Historische Bauten der Stadt Laupheim: ihre bau- und kulturgeschichtliche Bedeutung im Wandel der Zeit". Diss. Pädagogische Hochschule Weingarten.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Gesellschaft für Geschichte und Gedenken e. V. (1998). Christen und Juden in Laupheim. Laupheim: Gesellschaft für Geschichte und Gedenken e. V. ISBN 3-87437-151-4.

- Hecht, Cornelia, ed. (2004). Die Deportation der Juden aus Laupheim. Eine kommentierte Dokumentensammlung. Herrenberg: C. Hecht. ISBN 978-3-00-013113-4.

- Hoffmann, Andrea (2011). Schnittmengen und Scheidelinien: Juden und Christen in Oberschwaben. Tübingen: Tübinger Vereinigung für Volkskunde. ISBN 978-3-932512-69-8.

- Hüttenmeister, Nathanja (1998). Der jüdische Friedhof Laupheim. Eine Dokumentation. Laupheim: Verkehrs- und Verschönerungsverein Laupheim. ISBN 3-00-003527-3.

- Jansen, Katrin Nele; Brooke, Michael; Carlebach, Julius, eds. (1996). Biographisches Handbuch der Rabbiner 2. Die Rabbiner im Deutschen Reich 1871–1945 (in German). Vol. 2. München: De Gruyter Saur. ISBN 978-3-598-24874-0.

- Kohl, Waltraud (1965). "Die Geschichte der Judengemeinde in Laupheim". Diss. Pädagogische Hochschule Weingarten.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Köhlerschmidt, Antje; Neidlinger, Karl (eds.) (2008). Die jüdische Gemeinde Laupheim und ihre Zerstörung. Biografische Abrisse ihrer Mitglieder nach dem Stand von 1933. Laupheim: Gesellschaft für Geschichte und Gedenken e. V. ISBN 978-3-00-025702-5.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - Kullen, Siegfried (1994). "Spurensuche. Jüdische Gemeinden im nördlichen Oberschwaben". Blaubeurer geographische Hefte. 5: 1–79.

- Oswalt, Vadim (2000). Staat und ländliche Lebenswelt in Oberschwaben 1810–1871. (K)ein Kapitel im Zivilisationsprozeß?. Leinfelden-Echterdingen: DRW-Verlag. ISBN 3-87181-429-6.

- Säbel, Heinz. "Hundert Jahre Synagoge Laupheim". Hertha Nathorff Collection, 1813–1967. Center for Jewish History. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- Schäll, Ernst (1981). "Friedrich Adler (1878–1942). Ein Künstler aus Laupheim". Schwäbische Heimat. 32: 46–61.

- Schäll, Ernst (1993). "Kilian von Steiner; Bankier und Industrieller, Mäzen und Humanist". Schwäbische Heimat. 44: 4–11.

- Schäll, Ernst (1994). "Laupheim – einst eine große und angesehene Judengemeinde". In Kustermann, Abraham P.; Bauer, Dieter R. (eds.). Jüdisches Leben im Bodenseeraum. Zur Geschichte des alemannischen Judentums mit Thesen zum christlich-jüdischen Gespräch. Ostfildern: Schwabenverlag. pp. 59–89. ISBN 3-7966-0752-7.

- Schäll, Ernst (1996). "Der jüdische Friedhof in Laupheim". Schwäbische Heimat. 47: 404–417.

- Schenk (a), Georg (1970). "Die Juden in Laupheim". Ulm und Oberschwaben. 39: 103–120.

- Schenk (b), Georg (1979). "Die Juden in Laupheim". In Diemer, Kurt (ed.). Laupheim. Stadtgeschichte. Weißenhorn: Konrad. pp. 286–303. ISBN 3-87437-151-4.

- Schönhagen, Benigna (1998). Kilian von Steiner und Laupheim: "Ja, es ist ein weiter Weg von der Judenschule bis hierher ...". Marbach am Neckar: Deutsche Schillergesellschaft. ISBN 3-929146-81-9.

- Sauer, Paul (1966). Die jüdischen Gemeinden in Württemberg und Hohenzollern. Denkmale, Geschichte, Schicksale. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

- Wilke, Carsten, ed. (1996). Biographisches Handbuch der Rabbiner 1. Die Rabbiner der Emanzipationszeit in den deutschen, böhmischen und großpolnischen Ländern 1781–1871 (in German). München: De Gruyter Saur. ISBN 3-598-24871-7.

External links

- Webpage of the Museum Of Christians and Jews (in German)

- Alemannia Judaica – Jewish history in Baden-Württemberg

- Beit Hatfutsot, Museum of the Jewish People https://www.bh.org.il