History of experiments

The history of experimental research is long and varied. Indeed, the definition of an experiment itself has changed in responses to changing norms and practices within particular fields of study. This article documents the history and development of experimental research from its origins in Galileo's study of gravity into the diversely applied method in use today.

Ibn al-Haytham

The Arab physicist Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) used experimentation to obtain the results in his Book of Optics (1021). He combined observations, experiments and rational arguments to support his intromission theory of vision, in which rays of light are emitted from objects rather than from the eyes. He used similar arguments to show that the ancient emission theory of vision supported by Ptolemy and Euclid (in which the eyes emit the rays of light used for seeing), and the ancient intromission theory supported by Aristotle (where objects emit physical particles to the eyes), were both wrong.[2]

Experimental evidence supported most of the propositions in his Book of Optics and grounded his theories of vision, light and colour, as well as his research in catoptrics and dioptrics. His legacy was elaborated through the 'reforming' of his Optics by Kamal al-Din al-Farisi (d. c. 1320) in the latter's Kitab Tanqih al-Manazir (The Revision of [Ibn al-Haytham's] Optics).[3][4]

Alhazen viewed his scientific studies as a search for truth: "Truth is sought for its own sake. And those who are engaged upon the quest for anything for its own sake are not interested in other things. Finding the truth is difficult, and the road to it is rough. ...[5]

Alhazen's work included the conjecture that "Light travels through transparent bodies in straight lines only", which he was able to corroborate only after years of effort. He stated, "[This] is clearly observed in the lights which enter into dark rooms through holes. ... the entering light will be clearly observable in the dust which fills the air."[1] He also demonstrated the conjecture by placing a straight stick or a taut thread next to the light beam.[6]

Ibn al-Haytham employed scientific skepticism, emphasizing the role of empiricism and explaining the role of induction in syllogism. He went so far as to criticize Aristotle for his lack of contribution to the method of induction, which Ibn al-Haytham regarded as being not only superior to syllogism but the basic requirement for true scientific research.[7]

Something like Occam's razor is also present in the Book of Optics. For example, after demonstrating that light is generated by luminous objects and emitted or reflected into the eyes, he states that therefore "the extramission of [visual] rays is superfluous and useless."[8] He may also have been the first scientist to adopt a form of positivism in his approach. He wrote that "we do not go beyond experience, and we cannot be content to use pure concepts in investigating natural phenomena", and that the understanding of these cannot be acquired without mathematics. After assuming that light is a material substance, he does not further discuss its nature but confines his investigations to the diffusion and propagation of light. The only properties of light he takes into account are those treatable by geometry and verifiable by experiment.[9]

Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon's assertions in the Opus Majus that "theories supplied by reason should be verified by sensory data, aided by instruments, and corroborated by trustworthy witnesses"[10] were (and still are) considered "one of the first important formulations of the scientific method on record".[11]

Galileo Galilei

Galileo Galilei as a scientist performed quantitative experiments addressing many topics. Using several different methods, Galileo was able to accurately measure time. Previously, most scientists had used distance to describe falling bodies, applying geometry, which had been used and trusted since Euclid.[12] Galileo himself used geometrical methods to express his results. Galileo's successes were aided by the development of a new mathematics as well as cleverly designed experiments and equipment. At that time, another kind of mathematics was being developed—algebra. Algebra allowed arithmetical calculations to become as sophisticated as geometric ones. Algebra also allowed the discoveries of scientists such as Galileo—as well as later scientists such as Isaac Newton, James Clerk Maxwell and Albert Einstein—to be summarized by mathematical equations. These equations described physical relationships in a precise, self-consistent manner.

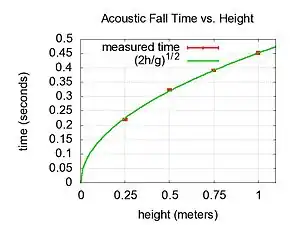

One prominent example is the "ball and ramp experiment."[13] In this experiment Galileo used an inclined plane and several steel balls of different weights. With this design, Galileo was able to slow down the falling motion and record, with reasonable accuracy, the times at which a steel ball passed certain markings on a beam.[14] Galileo disproved Aristotle's assertion that weight affects the speed of an object's fall. According to Aristotle's Theory of Falling Bodies, the heavier steel ball would reach the ground before the lighter steel ball. Galileo's hypothesis was that the two balls would reach the ground at the same time.

Other than Galileo, not many people of his day were able to accurately measure short time periods, such as the fall time of an object. Galileo accurately measured these short periods of time by creating a pulsilogon. This was a machine created to measure time using a pendulum.[15] The pendulum was synchronized to the human pulse. He used this to measure the time at which the weighted balls passed marks that he had made on the inclined plane. His measurements found that balls of different weights reached the bottom of the inclined plane at the same time and that the distance traveled was proportional to the square of the elapsed time.[16] Later scientists summarized Galileo's results as The Equation of Falling Bodies.[17][18]

| Distance d traveled by an object falling for time t where g is gravitational acceleration (~ 9.8 m/s2): | |

These results supported Galileo's hypothesis that objects of different weights, when measured at the same point in their fall, are falling at the same speed because they experience the same gravitational acceleration.

Antoine Lavoisier

The experiments of Antoine Lavoisier (1743–1794), a French chemist regarded as the founder of modern chemistry, were among the first to be truly quantitative. Lavoisier showed that although matter changes its state in a chemical reaction, the quantity of matter is the same at the end as at the beginning of every chemical reaction. In one experiment, he burned phosphorus and sulfur in air to see whether the results further supported his previous conclusion (Law of Conservation of Mass). In this experiment, however, he determined that the products weighed more than the original phosphorus and sulfur. He decided to do the experiment again. This time he measured the mass of the air surrounding the experiment as well. He discovered that the mass gained in the product was lost from the air. These experiments provided further support for his Law of Conservation of Mass.

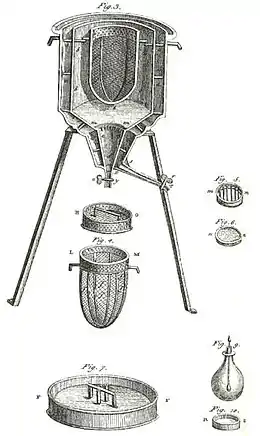

One of Lavoisier's experiments connected the worlds of respiration and combustion. Lavoisier's hypothesis was that combustion and respiration were one and the same, and combustion occurs with every instance of respiration. Working with Pierre-Simon Laplace, Lavoisier designed an ice calorimeter apparatus for measuring the amount of heat given off during combustion or respiration. This machine consisted of three concentric compartments. The center compartment held the source of heat, in this case the guinea pig or piece of burning charcoal. The middle compartment held a specific amount of ice for the heat source to melt. The outside compartment contained packed snow for insulation. Lavoisier then measured the quantity of carbon dioxide and the quantity of heat produced by confining a live guinea pig in this apparatus. Lavoisier also measured the heat and carbon dioxide produced when burning a piece of charcoal in the calorimeter. Using this data, he concluded that respiration was in fact a slow combustion process. He also discovered through precise measurements that these processes produced carbon dioxide and heat with the same constant of proportionality. He found that for 224 grains of "fixed air" (CO2) produced, 13 oz (370 g). of ice was melted in the calorimeter. Converting grains to grams and using the energy required to melt 13 oz (370 g). of ice, one can compute that for each gram of CO2 produced, about 2.02 kcal of energy was produced by the combustion of carbon or by respiration in Lavoisier's calorimeter experiments. This compares well with the modern published heat of combustion for carbon of 2.13 kcal/g.[19] This continuous slow combustion, which Lavoisier and Laplace supposed took place in the lungs, enabled the living animal to maintain its body temperature above that of its surroundings, thus accounting for the puzzling phenomenon of animal heat.[20] Lavoisier concluded, "La respiration est donc une combustion," That is, respiratory gas exchange is combustion, like that of burning a candle.

Lavoisier was the first to conclude by experiment that the Law of Conservation of Mass applied to chemical change.[21] His hypothesis was that the mass of the reactants would be the same as the mass of the products in a chemical reaction. He experimented on vinous fermentation, determining the amounts of hydrogen, oxygen, and carbon in sugar. Weighing a quantity of sugar, he added yeast and water in measured amounts, allowing the mixture to ferment. Lavoisier then measured the mass of the carbonic acid gas and water that were given off during fermentation and weighed the residual liquor, the components of which were then separated and analyzed to determine their elementary composition.[22] In this way he controlled a couple of potential confounding factors. He was able to capture the carbonic acid gas and water vapor that were given off during fermentation so that his final measurements would be as accurate as possible. Lavoisier concluded that the total mass of the reactants was equal to the mass of the final product and residue.[23] Moreover, he showed that the total mass of each constituent element before and after the chemical change remained the same. Similarly, he demonstrated via experimentation that the mass of products of combustion is equal to the mass of the reacting ingredients.

Louis Pasteur

The French biologist Louis Pasteur (1822-1895), regarded as the "Father of microbiological sciences and immunology", worked during the 19th century.[24] He postulated - and supported with experimental results - the idea that disease-causing agents do not spontaneously appear but are alive and need the right environment to prosper and multiply. Stemming from this discovery, he used experimentation to develop vaccines for chicken cholera, anthrax and rabies, and developed methods for reducing bacteria in some food products by heating them (pasteurization). Pasteur's work also led him to advocate (along with the English physician Dr. Joseph Lister) antiseptic surgical techniques. Most scientists of that day believed that microscopic life sprang into existence from spontaneous generation in non-living matter.

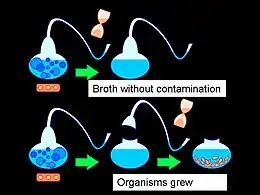

Pasteur's observations of tiny organisms under the microscope caused him to doubt spontaneous generation. He designed an experiment to test his hypothesis that life could not arise from where there is no life. He took care to control possible confounding factors. For example, he needed to make sure there was no life, even microscopic, in the flasks of broth he used as a test medium. He decided to kill any microscopic organisms already present by boiling the broth until he was confident that any microorganisms present were dead. Pasteur also needed to make sure that no microscopic organisms entered the broth after boiling, yet the broth needed exposure to air to properly test the theory. A colleague suggested a flask with a neck the shape of an "S" turned sideways. Dust (which Pasteur thought contained microorganisms) would be trapped at the bottom of the first curve, but the air would flow freely through.[25]

Thus, if bacteria should really be spontaneously generated, then they should be growing in the flask after a few days. If spontaneous generation did not occur, then the contents of the flasks would remain lifeless. The experiment appeared conclusive: not a single microorganism appeared in the broth. Pasteur then allowed the dust containing the microorganisms to mix with the broth. In just a few days the broth became cloudy from millions of organisms growing in it. For two more years he repeated the experiment in various conditions and locales to assure himself that the results were correct. In this way Pasteur supported his hypothesis that spontaneous generation does not occur.[26] Despite the experimental results supporting his hypotheses and his success curing or preventing various diseases, correcting the public misconception of spontaneous generation proved a slow, difficult process.

As he worked to solve specific problems, Pasteur sometimes revised his ideas in the light of the results of his experiments, as when faced with the task of finding the cause of disease devastating the French silkworm industry in 1865. After a year of diligent work he correctly identified a culprit organism and gave practical advice for developing a healthy population of moths. However, when he tested his own advice, he found disease still present. It turned out he had been correct but incomplete – there were two organisms at work. It took two more years of experimenting to find the complete solution.[27]

See also

References

- Alhazen, translated into English from German by M. Schwarz, from "Abhandlung über das Licht", J. Baarmann (ed. 1882) Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft Vol 36 as referenced on p.136 by Shmuel Sambursky (1974) Physical thought from the Presocratics to the Quantum Physicists ISBN 0-87663-712-8

- D. C. Lindberg, Theories of Vision from al-Kindi to Kepler, (Chicago, Univ. of Chicago Pr., 1976), pp. 60–7.

- Nader El-Bizri, "A Philosophical Perspective on Alhazen’s Optics," Arabic Sciences and Philosophy, Vol. 15, Issue 2 (2005), pp. 189–218 (Cambridge University Press)

- Nader El-Bizri, "Ibn al-Haytham," in Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia, eds. Thomas F. Glick, Steven J. Livesey, and Faith Wallis (New York – London: Routledge, 2005), pp. 237–240.

- Alhazen (Ibn Al-Haytham) Critique of Ptolemy, translated by S. Pines, Actes X Congrès internationale d'histoire des sciences, Vol I Ithaca 1962, as referenced on p.139 of Shmuel Sambursky (ed. 1974) Physical Thought from the Presocratics to the Quantum Physicists ISBN 0-87663-712-8

- p.136, as quoted by Shmuel Sambursky (1974) Physical thought from the Presocratics to the Quantum Physicists ISBN 0-87663-712-8

- Plott, C. (2000), Global History of Philosophy: The Period of Scholasticism, Motilal Banarsidass, p. 462, ISBN 81-208-0551-8

- Alhazen; Smith, A. Mark (2001), Alhacen's Theory of Visual Perception: A Critical Edition, with English Translation and Commentary of the First Three Books of Alhacen's De Aspectibus, the Medieval Latin Version of Ibn al-Haytham's Kitab al-Manazir, DIANE Publishing, pp. 372 & 408, ISBN 0-87169-914-1

- Rashed, Roshdi (2007), "The Celestial Kinematics of Ibn al-Haytham", Arabic Sciences and Philosophy, Cambridge University Press, 17: 7–55 [19], doi:10.1017/S0957423907000355, S2CID 170934544:

"In reforming optics he, as it were, adopted ‘‘positivism’’ (before the term was invented): we do not go beyond experience, and we cannot be content to use pure concepts in investigating natural phenomena. Understanding of these cannot be acquired without mathematics. Thus, once he has assumed light is a material substance, Ibn al-Haytham does not discuss its nature further, but confines himself to considering its propagation and diffusion. In his optics ‘‘the smallest parts of light’’, as he calls them, retain only properties that can be treated by geometry and verified by experiment; they lack all sensible qualities except energy."

- Bacon, Opus Majus, Bk.&VI.

- Borlik (2013), p. 132.

- Drake, Stillman; Swerdlow, Noel M.; Levere, Trevor Hardly. Essays on Galileo and the history and philosophy of science, Volume 3. Page 22. University of Toronto Press. 1999. ISBN 978-0-8020-4716-8.

- Solway, Andrew. Exploring forces and motion. Page 17. The Rosen Publishing Group. 2007. ISBN 978-1-4042-3747-6

- Stewart, James. Redlin, Lothar. Watson, Saleem. College Algebra. Page 562. Cengage Learning. 2008. ISBN 978-0-495-56521-5

- Massachusetts Medical Society, New England Surgical Society. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Volume 125. Page 314. Cupples, Upham & Co. 1891

- Tiner, John Hudson. Exploring the World of Physics: From Simple Machines to Nuclear Energy. New Leaf Publishing Group. 2006. ISBN 0-89051-466-6

- Longair, M.S. Theoretical concepts in physics: an alternative view of theoretical reasoning in physics. Page 37. Cambridge University Press. 2003. ISBN 978-0-521-52878-8

- Schutz, Bernard F. Gravity from the ground up. Page 3. Cambridge University Press. 2003. ISBN 978-0-521-45506-0

- Holmes (1987; p.188) The published value of the heat of combustion for carbon is usually expressed as 393.5 kJ/mol; unit conversion yields the figure in units for comparison of 2.13 kcal/g

- Holmes (1987; p.197)

- Bell (2005; p.44)

- Holmes (1987; p.382)

- Bell (2005; p.92)

- Simmers, Louise. Simmers-Nartker, Karen. Diversified Health Occupations. Page 10. Cengage Learning 2008. ISBN 978-1-4180-3021-6

- Dubos (1986; p.169)

- Debré, Patrice. Louis Pasteur. Page 300. JHU Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-8018-6529-9

- Dubos (1986; p.210)

- Bell, Madison Smartt (2005) Lavoisier in the Year One.. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 0-393-05155-2

- Borlik, Todd Andrew (2013). "More than Art: Clockwork Automata, the Extemporizing Actor, and the Brazen Head in Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay". In Hyman, Wendy Beth (ed.). The Automaton in English Renaissance Literature. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4094-7884-3.

- Holmes, Frederic Lawrence (1987) Lavoisier and the chemistry of life: an exploration of scientific creativity, Univ. Wisconsin Press. Reprint. ISBN 978-0-299-09984-8.

- Dubos, Rene J. (1986) Louis Pasteur: Free Lance of Science. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80262-1

- Kupelis, Theo; Kuhn, Karl F. (2007) In Quest of the Universe. Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7637-4387-1.