History of the Serbs

The History of the Serbs spans from the Early Middle Ages to present.[1] Serbs, a South Slavic people, traditionally live mainly in Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and North Macedonia. A Serbian diaspora dispersed people of Serb descent to Western Europe, North America and Australia.

| Part of a series on |

| Serbs |

|---|

|

| History of Serbia |

|---|

|

|

|

Middle Ages

Slavs settled in the Balkans during the 6th and 7th centuries, where they encountered and partially absorbed the remaining local population (Illyrians, Thracians, Dacians, Celts, Scythians).[2] One of those early Slavic peoples were Serbs.[3] According to De Administrando Imperio, a historiographical work compiled by the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (d. 959), migration of Serbs from White Serbia to Balkans occurred sometime during the reign of emperor Heraclius I (610-641) when they arrived in an area near Thessaloniki, but shortly afterwards they left that area and settled lands between the Sava and the Dinaric Alps.[4][5][6] By the time of the first reign of emperor Justinian II (685-695), who resettled several South Slavic groups from Balkans to Asia Minor, a group of Serbian settlers in the region of Bithynia were already christianized. Their settlement, the city of Gordoserba (Greek: Γορδόσερβα), had its bishop, who participated at the Council of Trullo (691-691).[7] In contemporary historiography and archaeology, the narratives of De Administrando Imperio have been reassessed as they contain anachronisms and factual mistakes. The account in DAI about the Serbs mentions that they requested from the Byzantine commander of present-day Belgrade to settle in the theme of Thessalonica, which was formed ca. 150 years after the reign of Heraclius which was in the 7th century. For the purposes of its narrative, the DAI formulates a mistaken etymology of the Serbian ethnonym which it derives from Latin servi (serfs).[8]

As the Byzantine Empire sought to establish its hegemony towards the Serbs, the narrative of the DAI sought to establish a historical hegemony over the Serbs by claiming that their arrival, settlement and conversion to Christianity was the direct result of the Byzantine interference in the centuries which preceded the writing of DAI.[9] Historian Danijel Dzino considers that the story of the migration from White Serbia after the invitation of Heraclius as a means of explanation of the settlement of the Serbs is a form of rationalization of the social and cultural change which the Balkans had undergone via the misinterpretation of historical events placed in late antiquity.[10]

After their initial settlement in the western regions of the Balkans, Serbs created their first state, the early medieval Principality of Serbia, that was ruled by the first Serbian dynasty, known in historiography as the Vlastimirović dynasty.[4] During their reigh, christianization of the Serbs was undergoing, as a gradual process, that was finalized by the middle of the 9th century.[11] Serbs also created local states in regions of Neretvanija, Zahumlje, Travunija and Duklja. Some scholars, like Tibor Živković and Neven Budak, doubt their Serbian ethnic identity and suppose that sources like De Administrando Imperio are based on data related to Serbian political rule.[12][13]

Early medieval Serbian areal was also attested by the Royal Frankish Annals, that note, under the entry for 822, that prince Ljudevit left his seat at Sisak and went to the Serbs.[14] According to Živković, the usage of the term Dalmatia in the document to refer both to the land where Serbs ruled as well as to the lands under the rule of Croat duke, was likely a reflection of the Franks' territorial aspirations towards the entire area of the former Roman Province of Dalmatia.[15] The same entry mentions "the Serbs, who are said to hold a great/large part of Dalmatia" (ad Sorabos, quae natio magnam Dalmatiae partem obtinere dicitur),[16][17][18] but according to John (Jr.) Fine, it was hard to find Serbs in this area since the Byzantine sources were limited to the southern coast, also it is possible that among other tribes exists tribe or group of small tribes of Serbs.[19][20] However, the mentioning of "Dalmatia" in 822 and 833 as an old geographical term by the authors of Frankish Annals was Pars pro toto with a vague perception of what this geographical term actually referred to.[21]

During the 11th and 12th centuries, Grand Principality of Serbia was ruled by the Vukanović dynasty. During that period, Serbs frequently fought against the neighbouring Byzantine Empire.[22]

Between 1166 and 1371, Serbs were ruled by the Nemanjić dynasty, founded by grand prince Stefan Nemanja (1166-1196), who conquered several neighbouring territories, including Kosovo, Duklja, Travunija and Zahumlje. Serbian state was elevated to a kingdom in 1217, during the reign of Nemanja's son, Stefan Nemanjić.[23] In the same time, Serbian Orthodox Church was organized as an autocephalous archbishopric in 1219,[24] through the efforts of Sava, who became the patron saint of Serbs.[25]

Over the next 140 years, Serbia expanded its borders. Its cultural model remained Byzantine, despite political ambitions directed against the empire. The medieval power and influence of Serbia culminated in the reign of Stefan Dušan, who ruled the state from 1331 until his death in 1355. and an empire In 1346, he was crowned as emperor, thus creating the Serbian Empire.[26] In the same time, Serbian Orthodox Church was raised to the Patriarchate (1346). Territory of the Empire included Macedonia, northern Greece, Montenegro, and almost all of Albania.[27] When Dušan died, his son Stephen Uroš V became Emperor.[28] With Turkish invaders beginning their conquest of the Balkans in the 1350s, a major conflict ensued between them and the Serbs, the first major battle was the Battle of Maritsa (1371),[29] in which the Serbs were defeated.[30] With the death of two important Serb leaders in the battle, and with the death of Stephen Uroš that same year, the Serbian Empire broke up into several small Serbian domains.[29] These states were ruled by feudal lords, with Zeta controlled by the Balšić family, Raška, Kosovo and northern Macedonia held by the Branković family and Lazar Hrebeljanović holding today's Central Serbia and a portion of Kosovo.[31] Hrebeljanović was subsequently accepted as the titular leader of the Serbs because he was married to a member of the Nemanjić dynasty.[29] In 1389, the Serbs faced the Ottomans at the Battle of Kosovo on the plain of Kosovo Polje, near the town of Pristina.[30] Both Lazar and Sultan Murad I were killed in the fighting.[32] The battle most likely ended in a stalemate, and Serbia did not fall to the Turks until 1459.[32] There exists c. 30 Serbian chronicles from the period between 1390 and 1526.[33]

Early modern period

The Serbs had taken an active part in the wars fought in the Balkans against the Ottoman Empire, and also organized uprisings.[34] Because of this, they suffered persecution and their territories were devastated.[34] Major migrations from Serbia into Habsburg territory ensued.[34] The period of Ottoman rule in Serbia lasted from the second half of the 15th century to the beginning of the 19th century, interrupted by three periods of Habsburg occupation during later Habsburg-Ottoman wars.

In early 1594, the Serbs in Banat rose up against the Ottomans.[35] The rebels had, in the character of a holy war, carried war flags with the icon of Saint Sava.[36] After suppressing the uprising, the Ottomans publicly incinerated the relics of Saint Sava at the Vračar plateau on April 27, 1595.[36] The incineration of Sava's relics provoked the Serbs, and empowered the Serb liberation movement. From 1596, the center of anti-Ottoman activity in Herzegovina was the Tvrdoš Monastery in Trebinje.[37] An uprising broke out in 1596, but the rebels were defeated at the field of Gacko in 1597, and were forced to capitulate due to the lack of foreign support.[37]

After allied Christian forces had captured Buda from the Ottoman Empire in 1686 during the Great Turkish War, Serbs from Pannonian Plain (present-day Hungary, Slavonia region in present-day Croatia, Bačka and Banat regions in present-day Serbia) joined the troops of the Habsburg Monarchy as separate units known as Serbian Militia.[38] Serbs, as volunteers, massively joined the Austrian side.[39] In 1688, the Habsburg army took Belgrade and entered the territory of present-day Central Serbia. Louis William, Margrave of Baden-Baden called Serbian Patriarch Arsenije III Čarnojević to raise arms against the Turks; the Patriarch accepted and returned to the liberated Peć. As Serbia fell under Habsburg control, Leopold I granted Arsenije nobility and the title of duke. In early November, Arsenije III met with Habsburg commander-in-chief, General Enea Silvio Piccolomini in Prizren; after this talk he sent a note to all Serb bishops to come to him and collaborate only with Habsburg forces.

A large migration of Serbs to Habsburg lands was undertaken by Patriarch Arsenije III.[40] The large community of Serbs concentrated in Banat, southern Hungary and the Military Frontier included merchants and craftsmen in the cities, but mainly refugees that were peasants.[40] Serbia remained under Ottoman control until the early 19th century, with the eruption of the Serbian Revolution in 1804.

Modern period

19th century

The uprising ended in the early 1830s, with Serbia's autonomy and borders being recognized, and with Miloš Obrenović being recognized as its ruler. The last Ottoman troops withdrew from Serbia in 1867, although Serbia's independence was not recognized internationally until the Congress of Berlin in 1878.[41] When the Principality of Serbia gained independence from the Ottoman Empire, Orthodoxy became crucial in defining the national identity, instead of language which was shared by other South Slavs (Croats and Muslims).[42]

20th century

Serbia fought in the Balkan Wars of 1912–13, which forced the Ottomans out of the Balkans and doubled the territory and population of the Kingdom of Serbia. In 1914, a young Bosnian Serb student named Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, which directly contributed to the outbreak of World War I.[43] In the fighting that ensued, Serbia was invaded by Austria-Hungary. Despite being outnumbered, the Serbs subsequently defeated the Austro-Hungarians at the Battle of Cer, which marked the first Allied victory over the Central Powers in the war.[44] Further victories at the battles of Kolubara and the Drina meant that Serbia remained unconquered as the war entered its second year. However, an invasion by the forces of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria overwhelmed the Serbs in the winter of 1915, and a subsequent withdrawal by the Serbian Army through Albania took the lives of more than 240,000 Serbs. Serb forces spent the remaining years of the war fighting on the Salonika front in Greece, before liberating Serbia from Austro-Hungarian occupation in November 1918.[45]

Serbs subsequently formed the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes with other South Slavic peoples. The country was later renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and was led from 1921 to 1934 by King Alexander I of the Serbian Karađorđević dynasty.[46] In the period of 1920–31, Serb and other South Slavic families of the Kingdom of Hungary (and Serbian-Hungarian Baranya-Baja Republic) were given the option to leave Hungary for the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and thereby change citizenship (these were called optanti).

During World War II, Yugoslavia was invaded by the Axis powers in April 1941. The country was subsequently divided into many pieces, with Serbia being directly occupied by the Germans.[47] Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) experienced persecution at the hands of the Croatian ultra-nationalist, fascist Ustaše, who attempted to exterminate the Serb population in death camps. More than half a million Serbs were killed in the territory of Yugoslavia during World War II.[48] Serbs in occupied Yugoslavia subsequently formed a resistance movement known as the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland, or the Chetniks. The Chetniks had the official support of the Allies until 1943, when Allied support shifted to the Communist Yugoslav Partisans, a multi-ethnic force, formed in 1941, which also had a large majority of Serbs in its ranks in the first two years of war, later, after the fall of Italy, September 1943. other ethnic groups joined Partisans in larger numbers.[47] At the end of the war, the Partisans, led by the Croat Josip Broz Tito, emerged victorious. Yugoslavia subsequently became a Communist state. Tito died in 1980, and his death saw Yugoslavia plunge into economic turmoil.[49]

Yugoslavia disintegrated in the early 1990s, and a series of wars resulted in the creation of five new states. The heaviest fighting occurred in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, whose Serb populations rebelled and sought unification with Serbia, which was then still part of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The war in Croatia ended in August 1995, with a Croatian military offensive known as Operation Storm crushing the Croatian Serb rebellion and causing as many as 200,000 Serbs to flee the country. The Bosnian War ended that same year, with the Dayton Agreement dividing the country along ethnic lines. In 1998–99, a conflict in Kosovo between the Yugoslav Army and Albanians seeking independence erupted into full-out war, resulting in a 78-day-long NATO bombing campaign which effectively drove Yugoslav security forces from Kosovo.[50] Subsequently, more than 200,000 Serbs and other non-Albanians fled the province.[51] On 5 October 2000, Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosević was overthrown in a bloodless revolt after he refused to admit defeat in the 2000 Yugoslav general election.[52]

Cultural history

Serbian Revival

The Serbian Revival refers to a period in the history of the Serbs between the 18th century and the de jure establishment of the Principality of Serbia (1878). It began in Habsburg territory, in Sremski Karlovci.[53] The "Serbian renaissance" is said to have begun in 17th-century Banat.[54] The Serbian Revival began earlier than the Bulgarian National Revival.[55] The first revolt in the Ottoman Empire to acquire a national character was the Serbian Revolution (1804–1817),[53] which was the culmination of the Serbian renaissance.[56] According to Jelena Milojković-Djurić: "The first literary and learned society among the Slavs was Matica srpska, founded by the leaders of Serbian revival in Pest in 1826."[57] Vojvodina became the cradle of the Serbian renaissance during the 19th century.[58] Vuk Stefanović Karadžić (1787–1864) was the most instrumental in this period.[59][60]

Maps

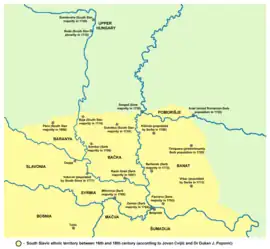

Ethnic territory of the Serbs and South Slavs in the Pannonian Plain between 16th and 18th century (according to Jovan Cvijić and Dr Dušan J. Popović)

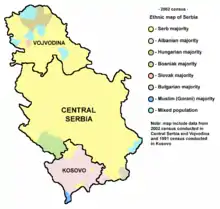

Ethnic territory of the Serbs and South Slavs in the Pannonian Plain between 16th and 18th century (according to Jovan Cvijić and Dr Dušan J. Popović) Serbs in Serbia as per 2002 census data for Central Serbia and Vojvodina, and 1991 census data for Kosovo

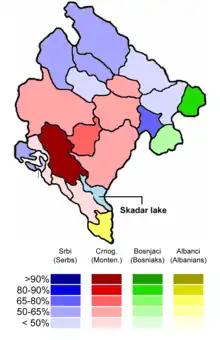

Serbs in Serbia as per 2002 census data for Central Serbia and Vojvodina, and 1991 census data for Kosovo Serbs in Montenegro as per 2003 census data

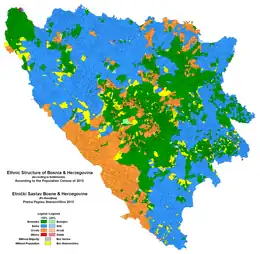

Serbs in Montenegro as per 2003 census data Serbs (blue) in Bosnia and Herzegovina as per 2013 census

Serbs (blue) in Bosnia and Herzegovina as per 2013 census

References

- Ćirković 2004.

- Miller 2005, p. 533.

- Fine 1991, p. 52-53.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 11.

- Tibor Živković; (2000) Sloveni i Romeji p 96-97; Istorijski Institut SANU, Beograd, ISBN 8677430229

- Siniša Mišić; (2014) Istorijska geografija srpskih zemalja od 6. do polovine 16. veka (in Serbian) p. 18; Magelan Pres, ISBN 8688873178

- Komatina 2014, p. 33–42.

- Curta 2001, p. 66: They were first given land in the province of Thessalonica, but no such theme existed during Heraclius’ reign. Emperor Constantine's explanation of the ethnic name of the Serbs as derived from servi is plainly wrong

- Kardaras 2011, p. 94.

- Dzino 2010, p. 112.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 15-17.

- Živković 2012, p. 161–162, 181–196.

- Budak, Neven (1994). Prva stoljeća Hrvatske (PDF). Zagreb: Hrvatska sveučilišna naklada. pp. 58–61. ISBN 953-169-032-4.

- Curta 2019, p. 109.

- Živković 2011, p. 395.

- Serbian Studies. Vol. 2–3. North American Society for Serbian Studies. 1982. p. 29.

...the Serbs, a people that is said to hold a large part of Dalmatia

- Dutton, Paul Edward (1993). Carolingian Civilization: A Reader. Broadview Press. p. 181. ISBN 9781551110035.

...who are said to hold a great part of Dalmatia

- Djokić, Dejan (2023). A Concise History of Serbia. Cambridge University Press. p. 61. ISBN 9781107028388.

'a people that is said to hold a large part of Dalmatia'. This was a reference to the ancient Roman province of Dalmatia, which extended deep into the western Balkan interior, from the eastern Adriatic coast to the valleys of the Ibar and Sava Rivers.

- John V. A. (Jr.) Fine; (2010) When Ethnicity Did Not Matter in the Balkans p. 35; University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0472025600

- Curta 2006, p. 136.

- Ančić, Mladen (1998). "Od karolinškoga dužnosnika do hrvatskoga vladara. Hrvati i Karolinško Carstvo u prvoj polovici IX. stoljeća". Zavod Za Povijesne Znanosti HAZU U Zadru. 40: 32.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 23-24.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 38.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 28.

- Cox 2002, p. 20.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 64.

- Cox 2002, p. 21.

- Cox 2002, p. 23.

- Cox 2002, pp. 23–24.

- Judah 2002, p. 5.

- Judah 2000, p. 27.

- Judah 2002, p. 7–8.

- Dvornik 1962, p. 174.

- Ga ́bor A ́goston; Bruce Alan Masters (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase Publishing. pp. 518–. ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7.

- Rajko L. Veselinović (1966). (1219-1766). Udžbenik za IV razred srpskih pravoslavnih bogoslovija. (Yu 68-1914). Sv. Arh. Sinod Srpske pravoslavne crkve. pp. 70–71.

- Nikolaj Velimirović (January 1989). The Life of St. Sava. St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-88141-065-5.

- Ćorović 2001, Преокрет у држању Срба

- Gavrilović, Slavko (2006), "Isaija Đaković" (PDF), Zbornik Matice Srpske za Istoriju (in Serbian), vol. 74, Novi Sad: Matica Srpska, Department of Social Sciences, Proceedings i History, p. 7, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2011, retrieved 21 December 2011

- Janićijević 1998, p. 70.

- Jelavich 1983a, p. 145.

- Ágoston & Masters 2009, pp. 518–519.

- Christopher Catherwood (1 January 2002). Why the Nations Rage: Killing in the Name of God. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-0-7425-0090-7.

- Miller 2005, p. 542.

- Pavlowitch 2002, p. 94.

- Miller 2005, pp. 542–543.

- Miller 2005, p. 544.

- Miller 2005, p. 545.

- Yugoslavian Front (WWII)#Casualties

- Miller 2005, pp. 546–553.

- Miller 2005, pp. 558–562.

- Gall, Carlotta (7 May 2000). "New Support to Help Serbs Return to Homes in Kosovo". The New York Times.

- Pavlowitch 2002, p. 225.

- M. Şükrü Hanioğlu (8 March 2010). A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-1-4008-2968-2.

- Francis Deák (1942). Hungary at the Paris Peace Conference: The Diplomatic History of the Treaty of Trianon. Columbia University Press. p. 370. ISBN 9780598626240.

- Viktor Novak (1980). Revue historique.

Иако је српски препород старији од бугар- ског, они су се надопуњивали. Књижевно „славеносрпски" и „сла- веноблгарски" су били блиски један другом, „нису се много разли- ковали и једнако су били доступни и за наше и за ...

- Fred Singleton (21 March 1985). A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples. Cambridge University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-521-27485-2.

- Jelena Milojković-Djurić (1994). Panslavism and national identity in Russia and in the Balkans, 1830-1880: images of the self and others. East European Monographs. p. 21. ISBN 9780880332910.

- Paul Robert Magocsi (2002). Historical Atlas of Central Europe. University of Toronto Press. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-8020-8486-6.

- Ingrid Merchiers (2007). Cultural Nationalism in the South Slav Habsburg Lands in the Early Nineteenth Century: The Scholarly Network of Jernej Kopitar (1780-1844). DCL Print & Sign. ISBN 978-3-87690-985-1.

The Serbian revival is especially linked with the name of Vuk Stefanovic Karadzic, who has been extensively studied and the subject of numerous monographs.

- Soviet Literature. Foreign Languages Publishing House. January 1956.

He helped Vuk Karadzich, prominent in the Serbian Renaissance, and one of the leading figures in the educational movement of his times,

Sources

- Primary sources

- Кунчер, Драгана (2009). Gesta Regum Sclavorum. Vol. 1. Београд-Никшић: Историјски институт, Манастир Острог.

- Moravcsik, Gyula, ed. (1967) [1949]. Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (2nd revised ed.). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 9780884020219.

- Pertz, Georg Heinrich, ed. (1845). Einhardi Annales. Hanover.

- Scholz, Bernhard Walter, ed. (1970). Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's Histories. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472061860.

- Thurn, Hans, ed. (1973). Ioannis Scylitzae Synopsis historiarum. Berlin-New York: De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110022858.

- Шишић, Фердо, ed. (1928). Летопис Попа Дукљанина (Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja). Београд-Загреб: Српска краљевска академија.

- Thallóczy, Lajos; Áldásy, Antal, eds. (1907). Magyarország és Szerbia közti összeköttetések oklevéltára 1198-1526. Budapest: Magyar Tudományos Akadémia.

- Wortley, John, ed. (2010). John Skylitzes: A Synopsis of Byzantine History, 811–1057. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139489157.

- Живковић, Тибор (2009). Gesta Regum Sclavorum. Vol. 2. Београд-Никшић: Историјски институт, Манастир Острог.

- Secondary sources

- Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce, eds. (2009). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York, NY: Facts On File. ISBN 9780816062591.

- Babac, Dušan M. (2016). The Serbian Army in the Great War, 1914-1918. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 9781910777299.

- Bataković, Dušan T. (1996). The Serbs of Bosnia & Herzegovina: History and Politics. Paris: Dialogue. ISBN 9782911527104.

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. ISBN 9782825119587.

- Bulić, Dejan (2013). "The Fortifications of the Late Antiquity and the Early Byzantine Period on the Later Territory of the South-Slavic Principalities, and their re-occupation". The World of the Slavs: Studies of the East, West and South Slavs: Civitas, Oppidas, Villas and Archeological Evidence (7th to 11th Centuries AD). Istorijski institut SANU. pp. 137–234. ISBN 9788677431044.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Ćirković, Sima (2014) [1964]. "The Double Wreath: A Contribution to the History of Kingship in Bosnia". Balcanica (45): 107–143. doi:10.2298/BALC1445107C.

- Cox, John K. (2002). The History of Serbia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313312908.

- Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139428880.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81539-0.

- Curta, Florin (2019). Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages (500-1300). Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004395190.

- DiNardo, Richard L. (2015). Invasion: The Conquest of Serbia, 1915. Santa Barbara: Praeger. ISBN 9781440800931.

- Dragnich, Alex N., ed. (1994). Serbia's Historical Heritage. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780880332446.

- Dragnich, Alex N. (2004). Serbia Through the Ages. Boulder: East European Monographs. ISBN 9780880335416.

- Dvornik, Francis (1962). The Slavs in European History and Civilization. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Dzino, Danijel (2010). Becoming Slav, Becoming Croat: Identity Transformations in Post-Roman and Early Medieval Dalmatia. Brill. ISBN 9789004186460.

- Đorđević, Miloš Z. (2010). "A Background to Serbian Culture and Education in the First Half of the 18th Century according to Serbian Historiographical Sources". Empires and Peninsulas: Southeastern Europe between Karlowitz and the Peace of Adrianople, 1699–1829. Berlin: LIT Verlag. pp. 125–131. ISBN 9783643106117.

- Đorđević, Života; Pejić, Svetlana, eds. (1999). Cultural Heritage of Kosovo and Metohija. Belgrade: Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of the Republic of Serbia. ISBN 9788680879161.

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1991) [1983]. The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Fryer, Charles (1997). The Destruction of Serbia in 1915. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780880333856.

- Gavrilović, Zaga (2001). Studies in Byzantine and Serbian Medieval Art. London: The Pindar Press. ISBN 9781899828340.

- Gumz, Jonathan E. (2009). The Resurrection and Collapse of Empire in Habsburg Serbia, 1914-1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521896276.

- Hehn, Paul N. (1971). "Serbia, Croatia and Germany 1941-1945: Civil War and Revolution in the Balkans". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 13 (4): 344–373. doi:10.1080/00085006.1971.11091249. JSTOR 40866373.

- Hupchick, Dennis P. (2002). The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. New York: Palgrave. ISBN 9780312299132.

- Ingrao, Charles; Samardžić, Nikola; Pešalj, Jovan, eds. (2011). The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 9781557535948.

- Isailović, Neven (2016). "Living by the Border: South Slavic Marcher Lords in the Late Medieval Balkans (13th–15th Centuries)". Banatica. 26 (2): 105–117.

- Isailović, Neven (2017). "Legislation Concerning the Vlachs of the Balkans Before and After Ottoman Conquest: An Overview". State and Society in the Balkans Before and After Establishment of Ottoman Rule. Belgrade: The Institute of History. pp. 25–42. ISBN 9788677431259.

- Isailović, Neven G.; Krstić, Aleksandar R. (2015). "Serbian Language and Cyrillic Script as a Means of Diplomatic Literacy in South Eastern Europe in 15th and 16th Centuries". Literacy Experiences concerning Medieval and Early Modern Transylvania. Cluj-Napoca: George Bariţiu Institute of History. pp. 185–195.

- Ivanović, Miloš; Isailović, Neven (2015). "The Danube in Serbian-Hungarian Relations in the 14th and 15th Centuries". Tibiscvm: Istorie–Arheologie. 5: 377–393.

- Ivić, Pavle, ed. (1995). The History of Serbian Culture. Edgware: Porthill Publishers. ISBN 9781870732314.

- Janićijević, Jovan, ed. (1998). The Cultural Treasury of Serbia. Belgrade: Idea, Vojnoizdavački zavod, Markt system. ISBN 9788675470397.

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983a). History of the Balkans: Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521252492.

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983b). History of the Balkans: Twentieth Century. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521274593.

- Jireček, Constantin (1911). Geschichte der Serben. Vol. 1. Gotha: Perthes.

- Jireček, Constantin (1918). Geschichte der Serben. Vol. 2. Gotha: Perthes.

- Judah, Tim (2000). The Serbs: History, Myth and the Destruction of Yugoslavia (2nd ed.). New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08507-5.

- Judah, Tim (2002). Kosovo: War and Revenge. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09725-2.

- Kalić, Jovanka (1995). "Rascia – The Nucleus of the Medieval Serbian State". The Serbian Question in the Balkans. Belgrade: Faculty of Geography. pp. 147–155.

- Kalić, Jovanka (2017). "The First Coronation Churches of Medieval Serbia". Balcanica (48): 7–18. doi:10.2298/BALC1748007K.

- Kardaras, Georgios (2011). "The Settlement of the Croats and Serbs on the Balkans in the Frame of the Byzantine-Avar Conflicts" (PDF). Bulgaria, the Bulgarians, Europe - Mythus, History, Modernity, Veliko Turnovo, Oct. 29-31. 2009. University Press "St. Cyril and Methodius". IV.

- Komatina, Predrag (2010). "The Slavs of the mid-Danube basin and the Bulgarian expansion in the first half of the 9th century" (PDF). Зборник радова Византолошког института. 47: 55–82.

- Komatina, Predrag (2014). "Settlement of the Slavs in Asia Minor During the Rule of Justinian II and the Bishopric των Γορδοσερβων" (PDF). Београдски историјски гласник: Belgrade Historical Review. 5: 33–42.

- Komatina, Predrag (2015). "The Church in Serbia at the Time of Cyrilo-Methodian Mission in Moravia". Cyril and Methodius: Byzantium and the World of the Slavs. Thessaloniki: Dimos. pp. 711–718.

- Krsmanović, Bojana (2008). The Byzantine Province in Change: On the Threshold Between the 10th and the 11th Century. Belgrade: Institute for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 9789603710608.

- Krstić, Aleksandar R. (2017). "Which Realm will You Opt for? – The Serbian Nobility Between the Ottomans and the Hungarians in the 15th Century". State and Society in the Balkans Before and After Establishment of Ottoman Rule. Belgrade: Institute of History, Yunus Emre Enstitüsü Turkish Cultural Centre. pp. 129–163. ISBN 9788677431259.

- Luttwak, Edward N. (2009). The Grand Strategy of the Byzantine Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674035195.

- Lyon, James B. (2015). Serbia and the Balkan Front, 1914: The Outbreak of the Great War. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781472580054.

- McCormick, Rob (2008). "The United States' Response to Genocide in the Independent State of Croatia, 1941–1945". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 3 (1): 75–98.

- MacKenzie, David (1996). "The Serbian Warrior Myth and Serbia's Liberation, 1804-1815". Serbian Studies: Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies. 10 (2): 133–148.

- MacKenzie, David (2004). "Jovan Ristić at the Berlin Congress 1878". Serbian Studies: Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies. 18 (2): 321–339.

- Meriage, Lawrence P. (1978). "The First Serbian Uprising (1804-1813) and the Nineteenth-Century Origins of the Eastern Question" (PDF). Slavic Review. 37 (3): 421–439. doi:10.2307/2497684. JSTOR 2497684. S2CID 222355180.

- Miller, Nicholas (2005). "Serbia and Montenegro". Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. Vol. 3. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 529–581. ISBN 9781576078006.

- Mitrović, Andrej (2007). Serbia's Great War 1914-1918. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 9781557534767.

- Obolensky, Dimitri (1974) [1971]. The Byzantine Commonwealth: Eastern Europe, 500-1453. London: Cardinal. ISBN 9780351176449.

- Orbini, Mauro (1601). Il Regno de gli Slavi hoggi corrottamente detti Schiavoni. Pesaro: Apresso Girolamo Concordia.

- Орбин, Мавро (1968). Краљевство Словена. Београд: Српска књижевна задруга.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Pavlovich, Paul (1989). The History of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Serbian Heritage Books. ISBN 9780969133124.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2002). Serbia: The History behind the Name. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 9781850654773.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2008). Hitler's new disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231700504.

- Pisarri, Milovan (2013). "Bulgarian Crimes Against Civilians in Occupied Serbia during the First World War". Balcanica (44): 357–390. doi:10.2298/BALC1344357P.

- Popović, Svetlana (2001). "The Serbian Episcopal sees in the thirteenth century". Старинар (51): 171–184.

- Radić, Radmila (2007). "Serbian Christianity". The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 231–248. ISBN 9780470766392.

- Samardžić, Radovan; Duškov, Milan, eds. (1993). Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. ISBN 9788675830153.

- Šćekić, Radenko; Leković, Žarko; Premović, Marijan (2015). "Political Developments and Unrests in Stara Raška (Old Rascia) and Old Herzegovina during Ottoman Rule". Balcanica (46): 79–106. doi:10.2298/BALC1546079S.

- Stanković, Vlada, ed. (2016). The Balkans and the Byzantine World before and after the Captures of Constantinople, 1204 and 1453. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. ISBN 9781498513265.

- Temperley, Harold W. V. (1919) [1917]. History of Serbia (PDF) (2 ed.). London: Bell and Sons.

- Todić, Branislav (1999). Serbian Medieval Painting: The Age of King Milutin. Belgrade: Draganić. ISBN 9788644102717.

- Todorović, Jelena (2006). An Orthodox Festival Book in the Habsburg Empire: Zaharija Orfelin's Festive Greeting to Mojsej Putnik (1757). Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754656111.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941-1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804779241.

- Trgovčević, Ljubinka (2007). "The Enlightenment and the Beginnings of Modern Serbian Culture" (PDF). Balcanica (2006): 103–110.

- Uzelac, Aleksandar B. (2011). "Tatars and Serbs at the end of the Thirteenth Century". Revista de istorie Militara. 5–6: 9–20.

- Uzelac, Aleksandar B. (2015). "Foreign Soldiers in the Nemanjić State - A Critical Overview". Belgrade Historical Review. 6: 69–89.

- Uzelac, Aleksandar B. (2018). "Prince Michael of Zahumlje – a Serbian ally of Tsar Simeon". Emperor Symeon's Bulgaria in the History of Europe's South-East: 1100 years from the Battle of Achelous. Sofia: St Kliment Ohridski University Press. pp. 236–245.

- Zens, Robert W. (2012). "In the Name of the Sultan: Haci Mustafa Pasha of Belgrade and Ottoman Provincial Rule in the Late 18th Century". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 44 (1): 129–146. doi:10.1017/S0020743811001280. JSTOR 41474984. S2CID 162893473.

- Živković, Tibor; Bojanin, Stanoje; Petrović, Vladeta, eds. (2000). Selected Charters of Serbian Rulers (XII-XV Century): Relating to the Territory of Kosovo and Metohia. Athens: Center for Studies of Byzantine Civilisation.

- Живковић, Тибор (2000). Словени и Ромеји: Славизација на простору Србије од VII до XI века (The Slavs and the Romans). Београд: Историјски институт САНУ, Службени гласник. ISBN 9788677430221.

- Живковић, Тибор (2002). Јужни Словени под византијском влашћу 600-1025 (South Slavs under the Byzantine Rule 600-1025). Београд: Историјски институт САНУ, Службени гласник. ISBN 9788677430276.

- Живковић, Тибор (2004). Црквена организација у српским земљама: Рани средњи век (Organization of the Church in Serbian Lands: Early Middle Ages). Београд: Историјски институт САНУ, Службени гласник. ISBN 9788677430443.

- Живковић, Тибор (2006). Портрети српских владара: IX-XII век (Portraits of Serbian Rulers: IX-XII Century). Београд: Завод за уџбенике и наставна средства. ISBN 9788617137548.

- Živković, Tibor (2007). "The Golden Seal of Stroimir" (PDF). Historical Review. Belgrade: The Institute for History. 55: 23–29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-24. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

- Živković, Tibor (2008). Forging unity: The South Slavs between East and West 550-1150. Belgrade: The Institute of History, Čigoja štampa. ISBN 9788675585732.

- Živković, Tibor (2010). "On the Beginnings of Bosnia in the Middle Ages". Spomenica akademika Marka Šunjića (1927-1998). Sarajevo: Filozofski fakultet. pp. 161–180.

- Živković, Tibor (2011). "The Origin of the Royal Frankish Annalist's Information about the Serbs in Dalmatia". Homage to Academician Sima Ćirković. Belgrade: The Institute for History. pp. 381–398. ISBN 9788677430917.

- Živković, Tibor (2012). De conversione Croatorum et Serborum: A Lost Source. Belgrade: The Institute of History.

- Živković, Tibor (2013a). "On the Baptism of the Serbs and Croats in the Time of Basil I (867–886)" (PDF). Studia Slavica et Balcanica Petropolitana (1): 33–53.

- Živković, Tibor (2013b). "The Urban Landcape [sic] of Early Medieval Slavic Principalities in the Territories of the Former Praefectura Illyricum and in the Province of Dalmatia (ca. 610-950)". The World of the Slavs: Studies of the East, West and South Slavs: Civitas, Oppidas, Villas and Archeological Evidence (7th to 11th Centuries AD). Belgrade: The Institute for History. pp. 15–36. ISBN 9788677431044.

External links

- Byzantine Illiricum - The Slavs Settlement (History of Balkan, part 1, Official channel)

- Byzantine Illiricum - The Slavs Settlement (History of Balkan, part 2, Official channel)

- Byzantine Illiricum - The Slavs Settlement (History of Balkan, part 3, Official channel)

- Byzantine Dalmatia - The Arrival of Serbs (History of Balkan, part 1, Official channel)

- Byzantine Dalmatia - The Arrival of Serbs (History of Balkan, part 2, Official channel)

- Byzantine Dalmatia - The Arrival of Serbs (History of Balkan, part 3, Official channel)

- Ćorović, Vladimir (2001). "Istorija srpskog naroda".