History of Germans in Poland

The history of Germans in Poland dates back almost a millennium. Poland was at one point Europe's most multiethnic state during the medieval period. Its territory covered an immense plain with no natural boundaries, with a thinly scattered population of many ethnic groups, including the Poles themselves, Germans in the cities of West Prussia, and Ruthenians in Lithuania. 5 to 10% of immigrants were German settlers.[1] (In the Middle Ages, there was no homogeneous German state; the label "German" generally refers to German-speaking people, including Germanized Polabian Slavs and Lusatian Sorbs.[1][2])

The Polish princes granted burghers in the cities, many of whom were German speaking, autonomy according to the "Magdeburg rights", modeled on the laws of the cities of ancient Rome.[3] In this way, cities emerged of the German-Western European medieval type. Before the 13th century ended, around one hundred Polish towns had Magdeburg-style municipal institutions. (Adoption of Magdeburg laws should not be equated with German colonization in Poland, as the laws were used in many places inhabited solely by Poles.[1]) The governing classes[1] in these towns were increasingly German and German-speaking. At the synod of Łęczyca in 1285, Archbishop Jakub Świnka of Gniezno warned that Poland might become a "new Saxony" if German negligence for Polish language, customs, clergy and ordinary people went unchecked. By the end of the Middle Ages significant populations in a number of western Polish cities were German-speaking, and some municipal documents were written partly in German (until the transition to Latin, and later to Polish[4]).

History

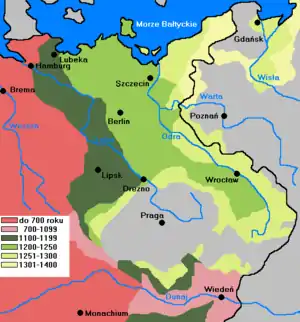

The 13th century brought fundamental changes to the structure of Polish society and its political system. Because of the fragmentation and constant internal conflicts, the Piast dukes were unable to stabilize Poland's external borders of the early Piast rulers. Western Farther Pomerania broke its political ties with Poland in the second half of the 12th century and from 1231 became a fief of the Margraviate of Brandenburg, which in 1307 extended its Pomeranian possessions even further east, taking over the Sławno and Słupsk areas. Pomerelia or Gdańsk Pomerania had been independent of the Polish dukes since 1227. In the mid-13th century, Bolesław II the Bald granted Lubusz Land to the Margraviate, which made possible the creation of the Neumark and had far reaching negative consequences for the integrity of the western border.[5]

The civil strife and foreign invasions, such as the Mongol invasions in 1241, 1259 and 1287, weakened and depopulated the many small Polish principalities, as the country was becoming progressively more subdivided. The depopulation and the increasing demand for labor in the developing economy caused a massive immigration of West European peasants, mostly German settlers, into Poland (early waves from Germany and Flanders in the 1220s).[6] The German, Polish and other new rural settlements were a form of feudal tenancy with immunity, and German town laws were often used as its legal basis. German immigrants were also important in the rise of the cities and the establishment of the Polish burgher (city-dwelling merchant) class; they brought with them West European laws (Magdeburg rights) and customs which the Poles adopted. From that time the Germans, who created early strong establishments (led by patriciates) especially in the urban centers of Silesia and other regions of western Poland, had been an increasingly influential minority in Poland.[5][7][8]

In 1228, the Acts of Cienia were signed into law by Władysław III Laskonogi. The titular Duke of Poland promised to provide a "just and noble law according to the council of bishops and barons". Such legal guarantees and privileges included the lower level landowners—knights, who were evolving into the class of lower and middle nobility known later as szlachta. The fragmentation period weakened the rulers and established a permanent trend in Polish history, whereby the rights and role of the nobility were expanded at the monarch's expense.[5]

Eastward settlement

The settlements involved internal colonization, associated with rural-urban migration by natives, and many of the Polish cities adopted laws based on those of the German towns of Lübeck and Magdeburg. Some economic methods were likewise imported from Germany.

Since the beginning of the 14th and 15th centuries, the Polish-Silesian Piast dynasty reinforced German settlers on the land, who in decades founded towns and villages under German town law, particularly under the law of the town of Magdeburg (Magdeburg law).

The 1257 foundation decree issued by Bolesław V the Chaste for Kraków was unusual insofar as it explicitly separated the local Polish population who already lived in the city,[10] in order to avoid depopulation of already existing settlements, leading to loss of taxes.[11] Often, the Ostsiedlung settlement was founded near a pre-existing fortress that was within the existing town, as for example with Poznań (Posen) and Kraków.[12]

Silesia

The Ostsiedlung in Silesia was initiated by Bolesław I and especially by his son Henry I and his wife Hedwig in the late 12th century. They became the first Slavic sovereigns outside the Holy Roman Empire to promote German settlements on a wide basis. Both began to invite German settlers in order to develop their realm economically and to extend their rule. As early as 1175 Bolesław I founded Lubensis Abbey and staffed the monastery with German monks from Pforta Abbey in Saxony. Before 1163, the abbey had been occupied by German Benedictines. The Cistercian abbey, its domain and the German settlers were excluded from local legislation, and subsequently the monks founded several German villages on their soil. During Henry I's reign, systematic settlement began. In a complex system a network of towns was founded in the western and southwestern parts of Silesia. These towns, economic and judicial centers, were surrounded by standardized built villages which were often constructed in a clearing in the forest. The earliest German land clearing area in Silesia appeared from 1147 until 1200 in the area of Goldberg and Löwenberg, two settlements founded by German miners. Goldberg and Löwenberg were also the first Silesian cities to receive German town law, in 1211 and 1217. This pattern of colonization was soon adopted in all other, already populated, parts of Silesia, were cities with German town law were often founded beside Slavic settlements.

In the early 14th century Silesia had about 150 towns, and the population more than quintupled. The townspeople were Germans, who now formed the majority of the overall population, while the Slavs usually lived outside the cities. In a process of peaceful assimilation, Lower and Middle Silesia became organically Germanized on the West bank of Oder. Upper Silesia retained a Slavic majority, but even there German villages and towns were established and there was increasing German agricultural cultivation of barren lands.

| Kaczyce, Śląsk (1447) c. 1620) |

Dębno, (Spisz) (c. 1450) |

Blizne, Podkarpacie (Red Ruthenia) (c. 1450) |

Haczów, Podkarpacie (Red Ruthenia) (1388) c. 1624 |

Binarowa, Podkarpacie (1400) c. 1500 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |

Lesser Poland

As late as the end of the Middle Ages, the original forest areas, especially the northern ones, lying in the fork of the Vistula, Wisłoka, and San were barely accessible for settlement due to the land's marshy nature. The area was intensively settled during the 13th to 15th centuries. The settlements were located according to the German Law within an area flanked by the Wisłok and Wisłoka rivers. On the northern and southern edges of the Carpathian Mountains German colonization had reached the Dunajec before 1300, whilst it filled wide mountain regions in upper Hungary. There were probably some isolated settlers in the area of Krosno, Sanok, Łańcut, Biecz and Rzeszów earlier. The Germans were usually attracted by kings seeking specialists in various trades, such as craftsmen and miners. They usually settled in newer market and mining settlements. The main settlement areas were in the vicinity of Krosno and some language islands in the Pits and Rzeszów regions. The settlers in the Pits region were known as Uplander Saxons. Until about the 15th century, the ruling classes of most cities in present-day Beskidian Piedmont consisted almost exclusively of Germans. The term Walddeutsche was coined by the Polish historians Marcin Bielski, 1531,[14] Szymon Starowolski 1632, bp. Ignacy Krasicki[15] and Wincenty Pol, and is also sometimes used to refer to Germans between Wisłoka and San River part of West Carpathians Plateau and Central Beskidian Piedmont in Poland.

German settlement in the Galician times (end of the 18th century), forced by the invading Austrian Habsburg.

Pomerelia

In Pomerelia, Ostsiedlung was started by the Pomerelian dukes[16] and focussed on the towns, whereas much of the countryside remained Slavic (Kashubians).An exception was the German settled Vistula delta(Vistula Germans), the coastal regions, and the Vistula valley.

Mestwin II in 1271 referred to the inhabitants of the "civitas" (town) of Danzig (Gdansk) as "burgensibus theutonicis fidelibus" (to the faithful German burghers).[17]

The settlers came from Low German areas like Holstein, the Low Countries, Flanders, Lower Saxony, Westphalia and Mecklenburg, but a few also from the Middle German Thuringia region.

Teutonic Knights

In 1226 Konrad I of Masovia invited the Teutonic Knights to help him fight the pagan, Baltic Old Prussians, who lived in a territory adjacent to his lands; substantial border warfare was taking place and Konrad's province was suffering from Prussian invasions. On the other hand, the Old Prussians themselves were at that time being subjected to increasingly forced (including papacy-sponsored crusades), but largely ineffective Christianization efforts. The Teutonic Order soon overstepped the authority and moved beyond the area granted them by Konrad (Chełmno Land or Kulmerland). In the following decades they conquered large areas along the Baltic Sea coast and established their monastic state. As virtually all of the Western Baltic pagans became converted or exterminated (the Prussian conquests were completed by 1283), the Knights confronted Poland and Lithuania, then the last pagan state in Europe. Teutonic wars with Poland and Lithuania continued for most of the 14th and 15th centuries. The Teutonic state in Prussia, populated by German settlers beginning in the 13th century, had been claimed as a fief and protected by the Popes and Holy Roman Emperors.[5][18]

Cultural heritage

In terms of cultural heritage, Silesia was more under German and Protestant influences than Moravia; and Catholicism has deeper roots in Moravia than in Bohemia and Silesia. Silesia is one of the current Polish provinces where Polish, Czech and German cultural influences have competed and coexisted for many hundreds of years. Historically speaking, the national differences in this area were connected with the question of social and religious identity. The organic unity between the towns and the countryside, typical of Silesia in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, was progressively replaced by marked social differences.[19]

Lower Silesia remained German until after the Second World War, when it became part of Poland. Breslau, the principal Silesian city, became Wrocław.[20] Today, according to the Polish-German good-neighbor treaty, the two countries are obliged to assume joint responsibility for goods representing cultural heritage.[21]

| Marklowice dolne, Moravia (1360 - 1739) |

Hrabova, Moravia (14th - 1564) |

Hervartov (Bardiów) (c. 1500) |

Chlastawa (north. Śląsk) c. 1637) |

Zamarski, Śląsk (c. 1731) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |

The remaining German minority in Poland (152,897 people were registered in the 2002 census) enjoys minority rights according to Polish minority law. There are German speakers throughout Poland, and most of the Germans live in the Opole Voivodship in Silesia. Bilingual signs are posted in some towns of the region. In addition, there are bilingual schools and German can be used instead of Polish in dealings with officials in several towns.

References

- Bogucka M., Samsonowicz H., Dzieje miast i mieszczaństwa w Polsce przedrozbiorowej, Wrocław 1986 p.22-56

- Wickham Ch., Medieval Europe, Yale University Press

- Tkaczyński J., Prawo ustrojowe Niemiec, Kraków 2015 UJ

- "Dopiero w połowie XVI wieku zaczęto pisać po polsku, Górnicki, Bielscy, Cyprian Bazylik, Budny, Wujek i Skarga, a przyczynił się do tego znany pisarz – Mikołaj Rey z Nagłowic, który w 1562 r. w utworze „Zwierzyniec” napisał: „A niechaj narodowie wżdy postronni znają, iż Polacy nie gęsi, iż swój język mają!”, [in:] Urbańczyk. Dwieście lat polskiego językoznawstwa: 1751-1950. 1993; "dopiero w roku 1600, zniosła rada miejska zagajanie sądów ławniczych po niemiecku; tak uporczywa była tradycja tu, w Poznaniu, Bieczu, i in. [in] Aleksander Brückner. Encyklopedia staropolska.

- Wyrozumski Historia Polski. 116-128

- John Radzilowski, A Traveller's History of Poland; Northampton, Massachusetts: Interlink Books, 2007, ISBN 1-56656-655-X, p. 260

- Jerzy Lukowski and Hubert Zawadzki, A Concise History of Poland, p. 14-16

- Norman Davies, Europe: A History , p. 366

- Aleksander Brückner. Encyklopedia staropolska, tom II. str. 12, Niemcy.

- Kancelaria miasta Krakowa w średniowieczu Uniwersytet Jagielloński, 1995, page 15

- The Historiography of the So-called "East Colonisation" and the Current State of Research, w: B. Nagy, M. Sebők (red.), The Man of Many Devices, Who Wandered Full Many Ways... Festschrift in Honour of Janos Bak, Budapest 1999, s. 654-667

- Brather, Sebastian (2001). Archäologie der westlichen Slawen. Siedlung, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im früh- und hochmittelalterlichen Ostmitteleuropa. Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde (in German). Vol. 30. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 156, 158. ISBN 3-11-017061-2.

- Franciszek Kotula. Pochodzenie domów przysłupowych w Rzeszowskiem. "Kwartalnik Historii Kultury Materialnej" Jahr. V., Nr. 3/4, 1957, S. 557

- Marcin Bielski or Martin Bielski; "Kronika wszystkiego swiata" (1551; "Chronicle of the Whole World"), the first general history in Polish of both Poland and the rest of the world.

- Ignacy Krasicki [in:] Kasper Niesiecki Herbarz [...] (1839-1846) tom. IX, page. 11.

- Hartmut Boockmann, Ostpreußen und Westpreußen, Siedler 2002, p. 161, ISBN 3-88680-212-4

- Howard B. Clarke, Anngret Simms, The Comparative History of Urban Origins in Non-Roman Europe: Ireland, Wales, Denmark, Germany, Poland, and Russia from the Ninth to the Thirteenth Century B.A.R., p.690, 1985

- John Radzilowski, A Traveller's History of Poland, p. 39-41

- Anna Czekanowska. Polish Folk Music: Slavonic Heritage - Polish Tradition 2006. p. 73

- Concise Encyclopaedia of World History, 2007

- Daily report: East Europe: United States. Foreign Broadcast Information Service, edit. 94, 1994